Rosamund Clifford

Rosamund Clifford (before 1150 – ca. 1176), often called "The Fair Rosamund" or the "Rose of the World", was famed for her beauty and was a mistress of King Henry II of England, famous in English folklore.

Life

Rosamund is believed to have been the daughter of the marcher lord Walter de Clifford and his wife Margaret. Walter was originally known as Walter fitz Richard (i.e. son of Richard), but his name was gradually changed to that of his major holding, first as steward, then as lord. This was Clifford Castle on the River Wye in Herefordshire. Rosamund had two sisters, Amice and Lucy. Amice married Osbern fitz Hugh of Richard's Castle, Herefordshire, and Lucy, Hugh de Say of Stokesay, Shropshire. She also had three brothers, Walter de Clifford (died 1221), Richard and Gilbert. Her name, "Rosamund", may have been influenced by the Latin phrase rosa mundi, which means "rose of the world."[1]

Rosamund grew up at Castle Clifford, before going to Godstow Nunnery, near Oxford, to be educated by the nuns.[2] Henry publicly acknowledged the liaison with Rosamund in 1174. When the affair ended, Rosamund retired to Godstow Abbey, where she died, not thirty years old, in 1176. According to Mike Ibeji, "there is ...no doubt that the great love of his life was Rosamund Clifford."[3] Rosamond, Countess Ida, my mother De Clifford was born in 1136 in Clifford, Herefordshire, the child of Walter and Margaret, daughter of Ralph de Toeni. She had one son with Henry Curtmantle Plantagenet England II in 1173. She died in 1176 in Woodstock, Oxfordshire, at the age of 40, and was buried in Oxford, Oxfordshire.

Legend

The traditional story recounts that King Henry adopted her as his mistress. To conceal his illicit amours from his Queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine, he conducted them within the innermost recesses of a complicated maze which he caused to be made in his park at Woodstock, Oxfordshire. Rumours having reached the ears of Queen Eleanor, the indignant lady contrived to penetrate the labyrinth, confronted her terrified and tearful rival, and forced her to choose between the dagger and the bowl of poison; Rosamund chose the latter and died.[4]

The poisoning incident is not mentioned in an account given by a chronicler of that time, John Brompton, Abbot of Jervaulx, and does not appear before the fourteenth century.[4]

The story was handed down for generations and gradually embroidered with various additional details, more or less scandalous, gathered around the central tale, as, for instance, that Rosamond presented Henry with the son who was afterwards known as William Longsword, Earl of Salisbury.[4] His mother was, however, Ida de Tosny, Countess of Norfolk.

Rosamund Clifford was reputedly one of the great beauties of the twelfth century and inspired ballads, poems, stories and paintings.[5]

Possible children

Historians are divided over whether or not Rosamund's relationship with the King produced children. Legend has falsely attributed to Rosamund another of Henry's illegitimate sons: Geoffrey Plantagenet, Archbishop of York (1151–1212). Her maternity in this case was only claimed centuries later. Geoffrey was apparently born before Henry and Rosamund met and is presumed to be the son of another otherwise unknown mistress.

Other stories

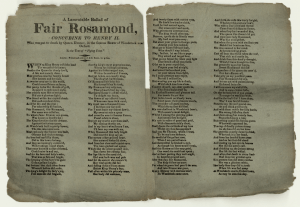

Rosamund's story first appears in fourteenth century French Chronicle of London, which purports to recount the confrontation with Queen Eleanor. In one version Rosamund is improbably described as having been roasted between two fires, stabbed, and left to bleed to death in a bath of scalding water by the Queen.[6] During the Elizabethan era, stories claiming that she had been murdered by Eleanor of Aquitaine gained popularity; but the Ballad of Fair Rosamund by Thomas Deloney (1612) and the Complaint of Rosamund by Samuel Daniel (1592) are both purely fictional. Most medieval chroniclers acknowledged that by 1173, Eleanor was held in close confinement, having raised her sons in rebellion against their father.[6]

The underground labyrinth was added to the tale in 1516. However, Robert Gambles cites a 1231 reference to "Rosamund's Chamber, with gardens, a cloister, and a well.[6] According to local tales, "Rosamund's Bower," is said to have been pulled down when Blenheim Palace was built. A pool on the grounds of Blenheim Palace is known as "Fair Rosamund's Well".[5]

The cup of poison first appears in a ballad of 1611.[6] Accounts made around the time of the dissolution report that, along with other engravings, Rosamund's tomb in the chapter house contained the depiction of a chalice.

She is thought to have entered Henry's life around the time that Eleanor was pregnant with her final child, John who was born on 24 December 1166 at Oxford. Indeed, Eleanor is known to have given birth to John at Beaumont Palace rather than at Woodstock because, it is speculated, Eleanor found Rosamund there at Woodstock.

Authorities differ over whether Rosamund stayed quietly in seclusion at Woodstock while Henry went back and forth between England and his continental possessions, or whether she travelled with him as a member of his household. If the former, the two of them could not have spent more than about a quarter of the time between 1166 and 1176 together (as historian Marion Meade puts it: "For all her subsequent fame, Rosamund must be one of the most neglected concubines in history").

Rosamund was also associated with the village of Frampton on Severn in Gloucestershire, another of her father Walter's holdings. Walter granted the mill at Frampton to Godstow Abbey for the good of the souls of Rosamund and his wife Margaret. The village green at Frampton became known as Rosamund's Green by the 17th century.[7]

A cultivar R. gallica var. officinalis 'Versicolor', with striped pink blooms, is commonly known as Rosa mundi.[8] Its connection to Rosamund Clifford dates to the sixteenth century.

Death and aftermath

Her death was remembered at Hereford Cathedral on 6 July, the same day as that of the king thirteen years later. Henry and the Clifford family paid for her tomb at Godstow in the choir of the monastery church and for an endowment that would ensure care of the tomb by the nuns. It became a popular local shrine until 1191, two years after Henry's death. Hugh of Lincoln, Bishop of Lincoln, while visiting Godstow, noticed Rosamund's tomb laden with flowers and candles. The bishop ordered her remains removed from the church: instead, she was to be buried outside "with the rest, that the Christian religion may not grow into contempt, and that other women, warned by her example, may abstain from illicit and adulterous intercourse." Her tomb was moved to the cemetery by the nuns' chapter house, where it could be visited until it was destroyed in the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII of England.[9] The remains of Godstow Priory still stand and are open to the public.

Paul Hentzner, a German traveller who visited England c.1599, records that her faded tombstone inscription read in part:

... Adorent, utque tibi detur requies Rosamunda precamur. ("Let them adore... and we pray that rest be given to you, Rosamund.") Followed by a rhyming epitaph: Hic jacet in tumba Rosamundi non Rosamunda, non redolet sed olet, quae redolere solet. ("Here in the tomb lies the rose of the world, not a pure rose; she who used to smell sweet, still smells--but not sweet.")[10]

Fiction

- Rosamund Clifford is the subject of Samuel Daniel's 1592 poem, "The Complaint of Rosamond."

- Rosamund is a German Singspiel by Anton Schweitzer on a text by Christoph Martin Wieland (Mannheim 1780)

- Rosmonda d'Inghilterra ("Rosamund of England") is an 1834 Italian opera by Gaetano Donizetti.

- Rosamund was the central character in the poem Rosemonde by Guillaume Apollinaire.[11]

- Rosamund is a character in the novel Eleanor the Queen (1955, 1983) by Norah Lofts.

- Rosamund is mentioned in the play and movie versions of The Lion in Winter (1966, 1968).

- Rosamund appears as "Rose Parrish" in Susan Howatch's family saga Penmarric (1971), a re-telling of the story of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine.

- Rosamund is a character in the novel The Courts of Love: The Story of Eleanor of Aquitaine (1987) by Jean Plaidy.

- Rosamund is mentioned in Virginia Henley's romance, The Falcon and the Flower (1988).

- Rosamund is a character in the novel The Book of Eleanor, A Novel of Eleanor of Aquitaine (2002) by Pamela Kaufman.

- Rosamund's affair with Henry II is detailed in Sharon Penman's novel Time and Chance (2002), and continued in Penman's Devil's Brood (2008).

- The relationship between Rosamund and Henry is a major framing device in Robin Paige's mystery novel, Death at Blenheim Palace (2006).

- Rosamund appears in the novel The Death Maze (2008) (published in the U.S. as The Serpent's Tale) by Ariana Franklin.

- Rosamund is mentioned as past mistress of Henry II in the novel The Time of Singing (2008) by Elizabeth Chadwick.

- Rosamund is a character in the novel The Captive Queen: A Novel of Eleanor of Aquitaine (2010) by Alison Weir.

- Rosamund is a character in Conrad Ferdinand Meyer's novel, about Thomas Becket and Henry II of England, Der Heilige (translated into English as "The Saint").

See also

Notes

- ↑ Anthony à Wood The life and times of Anthony Wood: antiquary, of Oxford, 1632-1695, described by himself. Printed for the Oxford historical society, at the Clarendon press, 1891. Page 341.

- ↑ Bingham, Jane. The Cotswolds: A Cultural History, Oxford University Press, 2010 ISBN 9780195398755

- ↑ Ibeji, Mike. "The Character and Legacy of Henry II", BBC-History, 20 June 2011

- 1 2 3 Matthews, W.H., Mazes and Labyrinths, Chap. XIX, Longmans Green and Co., London, 1922

- 1 2 "'Fair Rosamund' well to be restored at Blenheim Palace", BBC News (Oxford), July 20, 2014

- 1 2 3 4 Gambles, Robert. Great Tales from British, Amberley Publishing Limited, 2013, ISBN 9781445613499 p. 61

- ↑ Victoria County History of Gloucestershire: Frampton on Severn

- ↑ "BBC plant finder - Rosa mundi". Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ↑ Cole, William. The Unfortunate Royal Mistresses, Rosamond Clifford, and Jane Shore, Concubines to King Henry the Second, and Edward the Fourth, London, 1825 p. 8

- ↑ Hentzner, Paul. Travels in England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth

- ↑ Apollinaire, Guillaume (1913); Rees, Garnet (ed.) (1975) Alcools London, Athlone Press.

Sources

- Biography from Who's Who in British History (1998), H. W. Wilson Company. Who's Who in British History, Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1998.

- W. L. Warren, Henry II, 1973.

- Remfry. P.M., Clifford Castle, 1066 to 1299 (ISBN 1-899376-04-6)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fair Rosamund. |