USS Wolverine (IX-64)

_Lake_Michigan_1943.jpg) Wolverine at anchor in Lake Michigan on 6 April 1943. | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Seeandbee |

| Builder: | Detroit Shipbuilding Company[1] |

| Launched: | 9 November 1912[2] |

| Acquired: | 2 March 1942 |

| Commissioned: | 12 August 1942[3] |

| Decommissioned: | 7 November 1945[3] |

| Renamed: | Wolverine on 2 August 1942[3] |

| Struck: | 28 November 1945[3] |

| Fate: | scrapped in December 1947[3] |

| Notes: | O/N 211085[4] |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | side wheel paddle steamer |

| Tonnage: | |

| Displacement: | (Navy) 7,200 long tons (7,300 t)[3] |

| Length: | 500 ft (150 m)[2] |

| Beam: |

|

| Draft: | 15.5 ft (4.7 m)[3] |

| Installed power: | 12,000 ihp (8,900 kW)[2] |

| Propulsion: | One three-cylinder steam engine (1 66 in (167.6 cm) high-pressure cyl., 2 × 96 in (243.8 cm) low-pressure cyl.) fed by 6 single-ended & 3 double-ended coal-fired boilers.[2] |

| Speed: | 22 miles per hour (35.4 km/h; 19.1 kn)[2] |

| Complement: | (Navy) 270[3] |

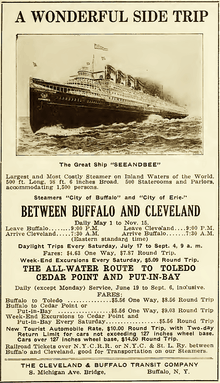

USS Wolverine (IX-64) was built as the Great Lakes side-wheel steamer Seeandbee launched 9 November 1912 that was converted into a freshwater aircraft carrier of the United States Navy in 1942 for advanced training of naval aviators in carrier take-offs and landings.[6] The Navy decommissioned Wolverine in 1945 and sold her for scrap in 1947.

Construction and design

Seeandbee, intended for overnight service between Cleveland and Buffalo, New York, was designed by naval architect Frank E. Kirby for the Cleveland and Buffalo Transit Company of Cleveland, Ohio.[2] The company's experience led it to require two basic design features directly related to the intended use in overnight, luxury passenger service for passengers wanting a good night's sleep.[7] First was paddle propulsion for the deck room gained by the side wheel type with the great width over paddle guards and thus more space for cabins and decks and an increased maneuvering capability and stability in rough weather over screw types.[7] Second, the more expensive and much heavier compound inclined steam engine was chosen due to its ability to develop 12,000 horsepower at low revolutions without the vibration associated with the higher revolutions required by lighter vertical types for similar power.[7]

The ship was built by the Detroit Shipbuilding Company, soon to be acquired and renamed American Ship Building Company, of Wyandotte, Michigan.[8][9] Seeandbee, the largest side-wheel steamer in the world at the time, was launched 9 November 1912.[2] According to the Interstate Commerce Commission the ship's tonnage was 6,381 GRT and 1,500 DWT.[5]

Hull and engineering

The ship's dimensions as built were 500 ft (152.4 m) length overall, 485 ft (147.8 m) between perpendiculars, 58 ft (17.7 m) molded hull beam, 97 ft 8 in (29.8 m) extreme beam over guards with extreme depth of hull at stem being 30 ft 4 in (9.2 m) and 23 ft 6 in (7.2 m) molded depth.[2] The hull was entirely steel with a double bottom extending almost 365 ft (111.3 m) feet containing water ballast and divided lengthwise with a watertight bulkhead and by transverse bulkheads into fourteen compartments.[2] Above that 3 ft (0.9 m) ballast compartment the ship was divided by eleven watertight bulkheads extending from keel to main deck with hydraulic doors operated from the engine room.[2] In total there were seven decks: tank top, orlop, main, promenade, gallery, upper and dome. Steel was used to the promenade deck with fire protection for beams above that level and fireproof doors provided compartmentalization and steel fire curtains in cargo spaces.[2] For fire alarm purposes the vessel was divided into fifty sections with fire hydrants spaced so that permanently attached hoses reached every point in the vessel and an extensive sprinkler system.[2]

Propulsion was by an inclined, three-cylinder steam engine below the main deck with only the main bearing tops, upper parts of the valves and handling levers above the main deck.[2] The engine was unique in using a Walschaert gear, normally used on locomotives, to drive a Corliss gear for the two low-pressure cylinders and the poppet type valves on the high-pressure portion.[10] The speed guarantee of 22 miles per hour (35.4 km/h; 19.1 kn) was met by the engine's indicated horsepower of 12,000 ihp (8,900 kW) at 31 revolutions per minute.[2][note 2] The high-pressure cylinder, 66 in (167.6 cm) in diameter, was centered between the two low-pressure cylinders of 96 in (243.8 cm) diameter with steam provided by six single ended and three double ended Scotch boilers forward of the engine room delivering steam at 165 pounds per square inch.[2] The single ended boilers were 14 ft (4.3 m) inside diameter by 10 ft 6 in (3.2 m) length and the double ended boilers were 14 ft 2.1875 in (4.3 m) mean diameter by 20 ft 5.5 in (6.2 m) length.[2] The two 32 ft 9 in (10.0 m) diameter paddle wheels each had eleven steel buckets 14 ft 10 in (4.5 m) long by 5 ft (1.5 m) wide.[2] Due to the restricted channels at both Cleveland and Buffalo additional maneuvering capability was required and a bow rudder and steam steering engine were provided.[2]

Washed air ventilation units provided fresh air for all interior spaces with exhaust fans for removal of foul air.[2] Three steam turbines drove generator sets for electricity for 4,500 electric lights, including the largest searchlight (32 in (81.3 cm)) on the Great Lakes, and the ship was extensively electrified for auxiliary functions.[2] Over 500 telephones were aboard, with one in every stateroom, officer's quarters and in booths in passenger areas as part of a public system and a private system for use in ship operations.[2]

Passenger accommodations

Passengers were accommodated in 510 rooms, of which 424 were regulation, 62 were fitted with private toilet and 24 were "parlors en suite" giving sleeping room for 1,500 persons and capable of carrying a total of 6,000 passengers and 1,500 tons of cargo loaded on the main deck.[2] Passengers boarded through a mahogany paneled lobby with a Tuscan theme having steward's and purser's offices, telephone booths and a stairway to the promenade deck protected by a vestibule with sliding doors.[2] Aft, extending to the stern, was the main dining room paneled in mahogany and white enamel with a banquet room on the starboard side and two private dining rooms to port.[2] Alcoves with bay windows provided some relatively private dining areas in the main dining room.[2] Stairs led to a buffet of old English tavern decor below the dining room.[2]

A feature of the vessel was the main saloon on the promenade deck that extended almost 400 ft (121.9 m) in length subdivided into sections with a book shop, flower booths, observation room and men's and ladies writing rooms.[2] A number of private parlors, each of different design containing beds and private baths and balconies, were set off the main saloon and aft, in an arrangement designed so that it could be heard both in the saloon and above in the atrium and ladies drawing room, was a balcony for an orchestra.[2] On the gallery deck was the ladies drawing room in Italian Renaissance style with built in seats and above, on the next deck, was an Atrium with sleeping rooms adjoining.[2] Amidships on the gallery deck was the lounge with seating and provision for light refreshments.[2]

Commercial operation

Seeandbee carried members of the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce to Buffalo on the maiden voyage with regular operations beginning from the East 9th Street pier in 1913.[11] In addition to the scheduled operation between Cleveland and Buffalo the vessel made special cruises to Detroit and Chicago and in summer.[11] Due to heavy losses in 1938 Cleveland and Buffalo Transit was liquidated in 1939 with the vessel acquired by the Chicago-based C&B Transit Company that operated the ship through 1941.[11]

Navy acquisition

Conversion

The Navy acquired Seeandbee on 12 March 1942 and designated her an unclassified miscellaneous auxiliary, IX-64 with conversion to a training aircraft carrier begun on 6 May.[3][12] The name Wolverine was approved on 2 August 1942 with the ship being commissioned on 12 August 1942.[12][13] Intended to operate on Lake Michigan, IX-64 received its name because the state of Michigan is known as the Wolverine State.[3]

New abilities

Key to her mission was the 550 ft (170 m) flight deck that she received. Wolverine began her new job in January 1943; her sister ship, USS Sable (IX-81) with a longer flight deck, joined Wolverine in May.[14]

In conjunction with NAS Glenview, the two paddle-wheelers afforded critical training in basic carrier operations to thousands of pilots and also to smaller numbers of Landing Signal Officers (LSOs). Wolverine and Sable enabled the pilots and LSOs to learn to handle take-offs and landings on a real flight deck.[15] Sable and Wolverine were a far cry from front-line carriers, but they accomplished the Navy's purpose: qualifying naval aviators fresh from operational flight training in carrier landings.[16]

Problems

Because Wolverine and Sable were not true carriers, they had certain limitations. One was that they had no elevators or hangar deck. When pilots used up the allotted spots on the flight deck for parking their aircraft, the day's operations were over and the carriers headed back to their pier in Chicago.

Another problem the two carriers had to contend with was (a lack of) wind over deck (WOD). Aircraft such as F6F Hellcats, F4U Corsairs, TBM Avengers and SBD Dauntlesses required certain minimum levels of WOD in order to land. When there was little or no wind on Lake Michigan, operations often had to be curtailed because the carriers couldn't generate sufficient speed to meet the wind on deck minimums.

Occasionally, when low-wind conditions persisted for several days and the pool of waiting aviators started to bunch up, the Navy turned to an alternate system of qualifications. The pilots qualified in SNJ Texans - even though most pilots had last flown the SNJ four or five months earlier.

End of career

Once the war was over, the need for such training ships also came to an end. The Navy decommissioned Wolverine on 7 November 1945; three weeks later, on 28 November, she was struck from the Naval Vessel Register.[3] Wolverine was then transferred to the War Shipping Administration on 14 November 1945[note 3] for disposal.[4] The ship was offered to U.S. citizens for either U.S. flag operation or scrapping and sold 21 November 1947 to A. F. Wagner Iron Works of Milwaukee, Wisconsin for $46,789 to be scrapped.[4]

Footnotes

- ↑ The cited reference is not the equivalent of today's Gross Tonnage standardized in the 1960s. It is likely, though not specified, one of several measures of Gross Register Tonnage of the registering authority and time.

- ↑ Inland and river vessels often used miles per hour instead of the oceanic knots.

- ↑ DANFS has the date as 26 November 1947, but that is after the documented sale on 21 November 1947 by the Maritime Administration (MARAD). MARAD shows the date of Navy action as 14 November 1945 after which the ship was offered for sale.

References

- ↑ Silverstone, Paul H (1965). US Warships of World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-773-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Marine Engineering: June 1913.

- 1 2 3 Maritime Administration Vessel Status Card.

- 1 2 Interstate Commerce Commission 1916, p. 319.

- ↑ Wallace, Irving; David Wallechinsky; Amy Wallace (6 May 1984). "Paddle-Wheel Aircraft Carriers". The Modesto Bee. Modesto, California. p. 48. Retrieved 4 January 2011.

- 1 2 3 Newell & Drayer 1916, pp. 92—93.

- ↑ Colton: Detroit Shipbuilding.

- ↑ Green's Marine Directory of the Great Lakes 31st Edition. 1939. pp. 102, 258, 331.

- ↑ Newell & Drayer 1916, p. 93.

- 1 2 3 Case Western Reserve University 1998.

- 1 2 "First Great Lakes Carrier, Wolverine, Is Commissioned". The Milwaukee Journal. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: United Press. 22 August 1942. p. 3. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- ↑ "First Lakes Carrier Completed". The Daily Times. Beaver and Rochester Pennsylvania. 21 August 1942. p. 6. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ↑ Fry, Steve (23 April 2004). "Out of a watery grave WWII plane restored decades after it went down". The City-Journal. Topeka, Kansas. Retrieved 4 January 2011.

- ↑ "A Stranger on the Lakes". Herald-Journal. Spartanburg, South Carolina. 26 August 1942. p. 3. Retrieved 4 January 2011.

Bibliography

- Case Western Reserve University (13 May 1998). "SEEANDBEE - The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History". Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Case Western Reserve University. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- Colton, T (22 September 2014). "Detroit Shipbuilding, Detroit MI and Wyandotte MI". ShipbuildingHistory. ShipbuildingHistory. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- Interstate Commerce Commission (1916). "Appenxix, Exhibit No. 1 (Rates Via Rail-and-Lake Routes)". Interstate Commerce Commission Reports: Reports and Decisions of the Interstate Commerce Commission (December 1915 to January 1916). Washington: Government Printing Office. XXXVII. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- International Marine Engineering (1913). "Side Wheel Passenger Steamer See-and-Bee". International Marine Engineering. New York, New York: Aldrish Publishing Company. XVIII (6): 252–258. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- Maritime Administration. "Wolverine (IX-64)". Ship History Database Vessel Status Card. U.S. Department of Transportation, Maritime Administration. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- Naval History And Heritage Command. "Sable". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History And Heritage Command. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- Naval History And Heritage Command. "Wolverine". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History And Heritage Command. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- Newell, F. H.; Drayer, C. E. (1916). Engineering as a Career. New York: D. Van Nostrand Company. LCCN 16002426.

- Silverstone, Paul H (1965). US Warships of World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-773-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to USS Wolverine (IX-64). |

- navsource.org: USS Wolverine

- Sunken Corsair pulled from Lake Michigan http://www.chicagobreakingnews.com/2010/11/world-war-ii-fighter-plane-lake-michigan-recovery-waukegan.html