Christina the Astonishing

| Saint Christina the Astonishing | |

|---|---|

|

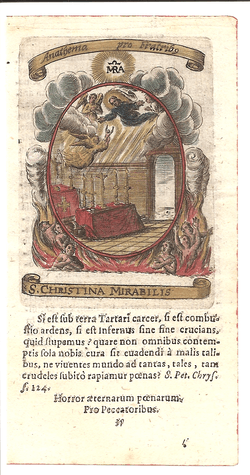

Christina the Astonishing appearing in the 1630 Fasti Mariani calendar of saints - feast day July 24th front of card. | |

| Born |

1150 Brustem, County of Loon |

| Died |

24 July 1224 Sint-Truiden, County of Loon |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church, Folk Catholicism, Belgium |

| Feast | July 24 |

| Patronage | Millers, people with mental disorders, mental health workers |

Christina the Astonishing (c.1150 – 24 July 1224), also known as Christina Mirabilis, was a Christian holy-woman born in Brustem (near Sint-Truiden), Belgium. She was considered a saint in her own time, and for centuries following her death, as noted by her appearance in the Fasti Mariani Calendar of Saints of 1630,[1] and Butler's Lives of the Saints - Concise Edition published in the 18th Century.[Literary 1]

Her notoriety began when she was 21 years old. About to be buried and already in the church resting in an open coffin, according to the custom of the time, during the Agnus Dei of her funeral Mass she arose, stupefying with amazement the whole city of St. Trond, which had witnessed this wonder. She died at the age of seventy-four.

Christina receives attention today for the strange descriptions of her miracles as much as for her faith. Her memorial day is 24 July.

Life

Christina was born to a pagan family, the youngest of three daughters.[2] After being orphaned at the age of fifteen, she worked taking the herds to pasture.[3] She suffered a massive seizure when she was in her early 20s. Her condition was so severe that witnesses assumed she had died. A funeral was held, but during the service, she "arose full of vigor, stupefying with amazement the whole city of Sint-Truiden, which had witnessed this wonder. "She levitated up to the rafters, later explaining that she could not bear the smell of the sinful people there."[4]

She related that she had witnessed Heaven, Hell and Purgatory. She said that as soon as her soul was separated from her body, angels conducted it to a very gloomy place, entirely filled with souls whose torments endured there were such that it was impossible for them to describe. She claimed that she had been offered a choice either to remain in heaven or return to earth to perform penance to deliver souls from the flames of Purgatory.[3] Christina agreed to return to life and arose that same moment. She told those around her that for the sole purpose of relief of the departed and conversion of sinners did she return. The words of a faithful maid had converted her into a Christian.

Christina renounced all comforts of life, reduced herself to extreme destitution, dressed in rags, lived without home or hearth, and not content with privations she eagerly sought all that could cause her suffering. At first, she fled human contact; and suspected of being possessed, was jailed. Upon her release, she took up the practice of extreme penance.[2]

Thomas of Cantimpré, then a canon regular who was a professor of theology, wrote a report eight years after her death, based on accounts of those who knew her. Cardinal Jacques de Vitry, who met with her, said that she would throw herself into burning furnaces and there suffered great tortures for extended times, uttering frightful cries, yet coming forth with no sign of burns upon her. In winter she would plunge into the frozen Meuse River for hours and even days and weeks at a time, all the while praying to God and imploring God's mercy. She sometimes allowed herself to be carried by the currents downriver to a mill where the wheel "whirled her round in a manner frightful to behold," yet she never suffered any dislocations or broken bones. She was chased by dogs which bit her.

After being incarcerated a second time, she moderated her approach somewhat, upon her release.[2] Christina died at the Dominican Monastery of Saint Catherine in Sint-Truiden, of natural causes, aged 74. The prioress there later testified that, despite her behavior, Christina would humbly and fully obey any command given her by the prioress.

"We have," says St. Robert Bellarmine, "reason for believing his testimony, since he has for guarantee another grave author, James de Vitry, Bishop and Cardinal, and because he relates what happened in his own time, and even in the province where he lived. Besides, the sufferings of this admirable virgin were not hidden. Every one could see that she was in the midst of the flames without being consumed, and covered with wounds, every trace of which disappeared a few moments afterwards. But more than this was the marvellous life she led for forty-two years after she was raised from the dead, God clearly showing that the wonders wrought in her by virtue from on high. The striking conversions which she effected, and the evident miracles which occurred after her death, manifestly proved the finger of God, and the truth of that which, after her resurrection, she had revealed concerning the other life."

Thus, argues Bellarmine, "God willed to silence those libertines who make open profession of believing in nothing, and who have the audacity to ask in scorn, Who has returned from the other world? Who has ever seen the torments of Hell or Purgatory? Behold two witnesses. They assure us that they have seen them, and that they are dreadful. What follows, then, if not that the incredulous are inexcusable, and that those who believe and nevertheless neglect to do penance are still more to be condemned?"

Modern interpretations

Modern scholarly opinion has generally held that Christina's Vita is an example of credulous medieval superstition.[3] Historian Barbara Newman finds that there is reason to understand Christina's behavior in terms of hysteria.[5] Sallie Baxendale notes that "[f]rom a medical perspective, the analysis of contemporary accounts of her afflictions provide compelling evidence of status epilepticus, olfactory auras, and probable frontal lobe epilepsy, with frequent secondary generalization."[6] Robert Sweetman contends that Christina's idiosyncratic life has taken an "outsized place" in the scholarly study of Medieval women's spirituality.[2]

Patronage

St. Christina the Astonishing has been recognized as a saint from the 12th century to current times. She was placed in the calendar of the saints by at least two bishops of the Catholic Church in two different centuries (17th & 19th) that also recognized her life in a religious order and preservation of her relics. The Catholic Church allows and recognizes veneration of saints upheld by the laity; canonization should be understood as a re-affirming of the more notable examples of Christian life as mentioned in the Catechism of the Catholic Church, and Saint Christina the Astonishing, having early Church recognition, is due her title of Saint as stated by the Church's Magisterium and Sacred Tradition.[Literary 2] Veneration of Christina the Astonishing has never been formally approved by the Catholic Church, but there remains a strong devotion to her in her native region of Limburg. Prayers are traditionally said to Christina to seek her intercession for millers, for those suffering from mental illness, and for mental health workers.

Cultural references

- Christina's story inspired the Nick Cave song "Christina the Astonishing", from the album Henry's Dream.

- Poets Jane Draycott and Lesley Saunders re-told her story in their collection Christina the Astonishing.[7]

- Christina is the subject of a school pageant in an episode of the Showtime television series, Nurse Jackie; the episode is entitled "The Astonishing." [8]

See also

References

- ↑ Lopez, Patrick. "Fasti Mariani Anni Menses Deus SS". MDZ Reader - Bayerische StaatsBibiothek Digital Archive. Brunner, A. & Smisek, J. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Sweetman, Robert (2006). "Christina the Astonishing". In Margaret Schaus. Women and Gender in Medieval Europe: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 132. ISBN 9780415969444.

- 1 2 3 Dickens, Andrea Janelle (2009). The Female Mystic: Great Women Thinkers of the Middle Ages. I.B.Tauris. p. 39-. ISBN 9780857712615.

- ↑ Saint Christina the Astonishing at the Patron Saint Index

- ↑ Newman, Barbara. "Possessed by the Spirit: Devout women, Demoniacs and the Apostolic Life in the Thirteenth Century", Speculum, 73, no.3 (1998) 764 JSTOR 2887496 doi:10.2307/2887496

- ↑ Baxendale, S., "The intriguing case of Christina the Astonishing", Neurology. 2008 May 20;70(21):2004-7. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000312574.85253.c0

- ↑ Draycott, Jane; Leslie Saunders; Peter Hay (ills.) (1998). Christina the Astonishing. Two Rivers Press. ISBN 978-1-901677-07-2.

- ↑ Nurse Jackie, season 3, episode 8

Literature

- ↑ Butler, Alban (July 5, 1991). Butler's Lives of the Saints: New Concise Edition (Revised ed.). San Francisco, CA, USA: HarperSanFrancisco; Revised edition. p. 466. ISBN 978-0060692995. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ↑ Ratzinger, Cd., Joseph (January 1, 1994). Catechism of the Catholic Church. United States of America: Ligouri Publications. p. 803. ISBN 0-89243-566-6. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- Thomas de Cantimpré, The Life of Christina the Astonishing. Ed. Margot H. King. Toronto, 1999. ISBN 0-920669-44-1

- Medieval Saints: A Reader. Ed. Mary-Ann Stouck. Toronto, 1999. ISBN 1-55111-101-2.

- Jennifer M. Brown, Three Women of Liège: A Critical Edition and Commentary on the Middle English Lives of Elizabeth of Spalbeek, Christina Mirabilis, and Marie d'Oignies. Turnhout: Brepols, 2009. ISBN 978-2-503-52471-9.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Christina the Astonishing. |