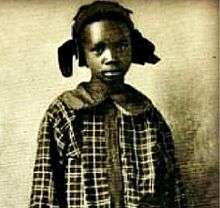

Sarah Rector

| Sarah Rector | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

March 3, 1902 Indian Territory now Taft, Oklahoma, U.S. |

| Died |

July 22, 1967 (aged 65) Kansas City, Missouri, U.S. |

| Resting place |

Blackjack Cemetery, Taft, Oklahoma, U.S. |

| Education | Tuskegee University |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 2 |

Sarah Rector (March 3, 1902 - July 22, 1967) born in Indian Territory before it became the state of Oklahoma in 1907 was an African American and a member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, best known for being the "Richest Colored Girl in the world" or the "Millionaire girl a member of the race" [1][2]

Life

Early life

Rector was born in 1902 near the all-black town of Taft in what was then Indian Territory to Joseph Rector and his wife, Rose McQueen (both born 1881).[3] Sarah Rector had five siblings in the all-Black town of Taft, located in the eastern portion of Oklahoma.[2] Joseph and Rosa Rector were African descendants of the Creek Nation Creek Indians before the Civil war and was part of the family Creek Nation after the The Treaty of 1866. As such, they and their descendants were listed as freedmen on the Dawes Rolls, by which they were entitled to land allotments under the Treaty of 1866 made by the United States with the Five Civilized Tribes.[4] Consequently, nearly 600 black children, or Creek Freedmen minors as they were called, inherited 160 acres of land each.[5] This was a mandatory step of the process of integration of the Indian Territory with Oklahoma Territory to form what is now the State of Oklahoma.[6][7]

Sarah's father Joseph was the son of John Rector, a Creek Freedman. John Rector's father Benjamin McQueen, was a slave of Reilly Grayson who was a Creek Indian. John Rector's mother Mollie McQueen was a slave of Creek leader, Opothole Yahola who fought in the Seminole wars and split with the tribe, moving his followers to Kansas.

The parcel allotted to Sarah Rector was located in Glenpool, 60 miles from where she and her family lived. It was typically considered inferior infertile soil, not suitable for farming, with better land being reserved white settlers and members of the tribe. The family lived simply but not in poverty, yet the $30 annual property tax on Sarah's parcel was such a burden that her father petitioned the Muskogee County Court to sell the land. He was denied because of certain restrictions placed on the land, for which reason he was required to continue paying the taxes.[5]

To help cover this expense, in February 1911, Joseph Rector leased Sarah's parcel to the Standard Oil Company. In 1913, the independent oil driller B.B. Jones drilled a well on the property which produced a “gusher” that began to bring in 2,500 barrels of oil a day. Rector began to receive a daily income of $300 from this strike. The law at the time required full-blooded Indians, black adults and children who were citizens of Indian Territory with significant property and money, to be assigned “well-respected” white guardians who often cheated them out of their lands.[8] Thus, as soon as this windfall began, pressure was placed to change Rector’s guardianship from her parents to a local white resident named T.J. (or J.T.) Porter, an individual known to the family. Multiple new wells on the site were also productive, and Rector’s allotment subsequently became part of the famed Cushing-Drumright Oil Field. In October 1913, Rector received royalties of $11,567.[5]

As news of Rector's wealth spread worldwide, she began to receive numerous requests for loans, money gifts, and even marriage proposals from four young men in Germany—despite the fact that she was only 12 years old.[5] Given her wealth, the Oklahoma Legislature declared her to be a white person, so that she would be allowed to travel in first-class accommodations on the railroad, as befitted her position.[3]

In 1914, an African American journal, The Chicago Defender, began to take in interest in Rector, just as rumors began to fly that she was a white immigrant who was being kept in poverty. The newspaper published an article claiming that her estate was being mismanaged by her and her “ignorant” parents, and that she was uneducated, dressed in rags, and lived in an unsanitary shanty. National African American leaders such as Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. DuBois became concerned about her welfare.[3] In June of that year, a special agent for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), James C. Waters Jr, sent a memo to Dubois regarding her situation. Waters had been corresponding with the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the United States Children's Bureau over concerns regarding the mismanagement of Rector’s estate. He wrote of her white financial guardian:

Is it not possible to have her cared for in a decent manner and by people of her own race, instead of by a member of a race which would deny her and her kind the treatment accorded a good yard dog?

This prompted Dubois to establish a Children’s Department of the NAACP, which would investigate claims of white guardians who were suspected of depriving black children out of their land and wealth. Washington also intervened to help the Rector family.[9]

Sarah and her siblings attended school in Taft, the family lived in a modern five-room cottage, and they owned an automobile. In October of that year, she was enrolled in the Children’s School, a boarding school for teenagers at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, headed by Washington. Upon graduation, she attended the Institute.[3]

Rector was already a millionaire by the time she had turned 18. She owned stocks and bonds, a boarding house, a bakery and restaurant in Muskogee, Oklahoma, as well as 2,000 acres of prime river bottomland. At that point, she left Tuskegee and, with her entire family, moved to Kansas City, Missouri. She purchased a house on 12th Street there still known as the Rector House. She soon married a local man, Kenneth Campbell. The wedding was a very private affair, with only her mother and the bridegroom's paternal grandmother present. The couple had three sons before they divorced in 1930.[3]

Later life

Rector lived a comfortable life, enjoying her wealth. She had a taste for fine clothing and fast cars. She was frequently ticketed by the police of the city for speeding. She hosted frequent gatherings at her home for the leading members of the nation's African American community, but also was later remembered for sending her chauffeur to drive the children of the neighborhood to school. Her husband partnered in 1928 with the auto dealer Homer Roberts and moved to Chicago to open Roberts-Campbell Motors, the second African American owned auto dealership. New car sales faltered with the onset of the depression and the venture soon closed. They divorced in 1930, and in 1934 she married William Crawford. They owned a restaurant where they entertained the likes of Count Basie and Duke Ellington. In the depression she lost the majority of her wealth as did many wealthy Americans.[10]

Rector died on July 22, 1967, at the age of 65. Her remains were buried in the city cemetery of her hometown of Taft.

References

- ↑ Chicago Defender November 4, 1922 page 1

- 1 2 The Crisis magazine. Stacey Patton. Spring 2010. Retrieved October 2014. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 "Remembering Sarah Rector, Creek Freedwoman". The African-Native American Genealogy Blog.

- ↑ "Rector, Sarah". BlackPast.org.

- 1 2 3 4 "Sarah Rector The Richest Black Girl In The World". Afrocentric Culture by Design. May 19, 2010. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ↑ Angela Y. Walton-Raji. "The African-Native American Genealogy Blog".

- ↑ Tonya Bolden (7 January 2014). Searching for Sarah Rector: The Richest Black Girl in America. Abrams. pp. 51–. ISBN 978-1-61312-531-1.

- ↑ "The Unlikely Baroness | This Land Press - Made by You and Me". This Land Press. 2015-03-24. Retrieved 2016-02-25.

- ↑ Patton, Stacey (October 20, 2011). "The Richest Colored girl in the world". Crisis. 117 (2).

- ↑ https://kathmanduk2.wordpress.com/2010/02/16/black-history-month-from-the-archives-sarah-rector-the-richest-colored-girl-in-america/

Further reading

- Kelvin Ray Rector (3 December 2010). Genocide: God Guide This Prisoner Toward Liberty. Bookstand Publishing. ISBN 978-1-58909-812-1.