Sceliages

| Sceliages | |

|---|---|

| |

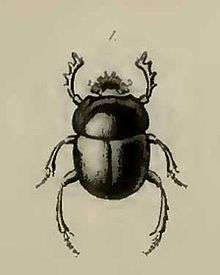

| Sceliages sp. from Great Karoo, South Africa | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Coleoptera |

| Suborder: | Polyphaga |

| Family: | Scarabaeidae |

| Genus: | Scarabaeus |

| Subgenus: | Sceliages Westwood, 1837 |

| Synonyms | |

|

Parascarabaeus Balthasar, 1961 | |

Sceliages, Westwood, ('σκέλος' = leg), is a sub-genus of the Scarabaeus dung beetles, and are obligate predators of spirostreptid, spirobolid and julid millipedes, having renounced the coprophagy for which they were named. The genus is near-endemic to Southern Africa, Sceliages augias exceptionally ranging as far north as the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Taxonomy

Currently seven species are recognised

- Sceliages adamastor LePeletier & Serville, 1828 - Cape, Orange Free State

- Sceliages augias Gillet, 1908 - Zambia, Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo

- Sceliages brittoni Zur Strassen, 1965 - Cape

- Sceliages difficilis Zur Strassen, 1965 - Zimbabwe, Natal, Transvaal, Gauteng

- Sceliages gagates Shipp, 1895 - Mozambique, Natal, Eastern Cape, Swaziland

- Sceliages granulatus Forgie & Grebennikov & Scholtz, 2002 - Northern Cape, Botswana

- Sceliages hippias Westwood, 1844 - Natal, Transvaal, Mpumalanga [1][2]

The sacred scarab, Scarabaeus sacer Linnaeus (1758), was once idolised by ancient Egyptians as the incarnation of the god Khepri, who guided the sun’s path across the heavens. The Scarabaeini may have evolved with other scarabaeines during the Cenozoic, stemming from lineages originating in the Lower Cretaceous or possibly as far back as the Lower Jurassic some 180–200 million years ago. Westwood felt that Ateuchus adamastor (Sceliages adamastor) did not differ enough from Scarabaeus (by an extra pait of spurs on the tibia) to merit generic separation.[3]

Ecology

Sceliages species have developed special adaptations to disarticulate millipedes - such as the shape of the clypeal margin, in particular the two front ‘teeth’, and the middle legs. The curvature of the meso tibiae is most evident in S. adamastor, fitting snugly around the circumference of the larger spirobolid, spirostreptid and julid millipedes. The adult male or female beetle straddles the subdued millipede and locks onto it particularly with the mid legs, and uses the front clypeal teeth to prise apart the ring segments of the millipede. Front legs assist in this operation, but the main work is done by the front clypeal teeth. The viscera or gut contents, the legs, and some bits of chitin are then used to form some 1-3 brood-balls depending on the size of the millipede. Brood-balls are prepared in a chamber underground and segment rings are discarded into the burrow. The brood-balls, each with one egg, are coated with a compacted layer of clayey soil to prevent desiccation, and are watched over by the female. Some Cephalodesmius species from Australia introduce additional food supplies as the larva develops, but this is not the case with Sceliages.

Sceliages species consume only millipedes (Diplopoda). Utilisation of millipedes by the Scarabaeinae can be both facultative and obligate, and has been documented since 1966, while active predation is recognised in Sceliages and Deltochilum species. Sceliages species are alerted to the presence of injured or freshly-killed millipedes by the smell of quinone-based defensive allomones - the millipedes are then pushed to a suitable site, buried and turned into pear-shaped, soil-encrusted brood-balls. In one observation in Namaqualand a Sceliages brittoni beetle was drawn to a millipede attacked by large reduviid bugs, Ectricodia crux. The beetle wrestled the injured millipede away from the reduviids and then buried it.[4]

Gallery

Sceliages adamastor preparing to bury millipede carcass

Sceliages hippias surrounded by millipede parts

Sceliages hippias brood chamber

Sceliages hippias moving millipede carcass

References

- ↑ R. & E. Stronkhorst. "Sceliages Westwood" (PDF). Dung beetles of Africa.

- ↑ Forgie, Shaun A.; Grebennikov, Vasily V.; Scholtz, Clarke H. (2002). "Revision of Sceliages Westwood, a millipede-eating genus of southern African dung beetles (Coleoptera : Scarabaeidae)" (PDF). Invertebrate Systematics. 16 (6): 931–955. doi:10.1071/IT01025.

- ↑ Westwood, J. O. (1841). "Descriptions of several new Species of Insects belonging to the Family of the Sacred Beetles". Transactions of the Zoological Society of London. 2: 155–164.

- ↑ R. & E. Stronkhorst. "Ecology". Dung beetles of Africa.

External links

Media related to Sceliages at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sceliages at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Sceliages at Wikispecies

Data related to Sceliages at Wikispecies- "Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London" 5: 11-12