Seorsumuscardinus

| Seorsumuscardinus Temporal range: Early Miocene (MN 4–5) | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Gliridae |

| Subfamily: | Glirinae |

| Genus: | Seorsumuscardinus Hans de Bruijn |

| Type species | |

| Seorsumuscardinus alpinus De Bruijn, 1998 | |

| Species | |

| |

| |

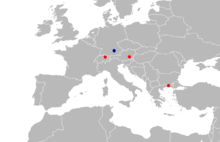

| Localities where Seorsumuscardinus has been found. MN 4 localities (S. alpinus) in red; the single MN 5 locality (S. bolligeri) in blue. | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Seorsumuscardinus is a genus of fossil dormice from the early Miocene of Europe. It is known from zone MN 4 (see MN zonation) in Oberdorf, Austria; Karydia, Greece; and Tägernaustrasse-Jona, Switzerland, and from zone MN 5 in a single site at Affalterbach, Germany. The MN 4 records are placed in the species S. alpinus and the sole MN 5 record is classified as the species S. bolligeri. The latter was placed in a separate genus, Heissigia, when it was first described in 2007, but it was reclassified as a second species of Seorsumuscardinus in 2009.

The two species of Seorsumuscardinus are known from isolated teeth, which show that they were medium-sized dormice with flat teeth. The teeth are all characterized by long transverse crests coupled with shorter ones. One of these crests, the anterotropid, distinguishes the two species, as it is present in the lower molars of S. alpinus, but not in those of S. bolligeri. Another crest, the centroloph, reaches the outer margin of the first upper molar in S. bolligeri, but not in S. alpinus. Seorsumuscardinus may be related to Muscardinus, the genus of the living hazel dormouse, which appears at about the same time, and the older Glirudinus.

Taxonomy

In 1992, Thomas Bolliger described some teeth of Seorsumuscardinus from the Swiss locality of Tägernaustrasse (MN 4; early Miocene, see MN zonation) as an indeterminate dormouse (family Gliridae) perhaps related to Eomuscardinus.[1] Six years later, Hans de Bruijn named the new genus and species Seorsumuscardinus alpinus on the basis of material from Oberdorf in Austria (also MN 4) and included fossils from Tägernaustrasse and from Karydia in Greece (MN 4) in Seorsumuscardinus.[2] In 2007, Jerome Prieto and Madeleine Böhme named Heissigia bolligeri as a new genus and species from Affalterbach in Bavaria (MN 5, younger than MN 4), and referred the Tägernaustrasse material to it, but failed to compare their new genus to Seorsumuscardinus.[3] Two years later, Prieto published a note to compare the two and concluded that they were referable to the same genus, but different species. Thus, the genus Seorsumuscardinus now includes the species Seorsumuscardinus alpinus from MN 4 and S. bolligeri from MN 5. Prieto provisionally placed the Tägernaustrasse material with S. alpinus.[4] He also mentioned Pentaglis földváry, a name given to a single upper molar from the middle Miocene of Hungary, which is now lost. Although the specimen shows some similarities with Seorsumuscardinus, published illustrations are too poor to confirm the identity of Pentaglis, and Prieto considered the latter name to be an unidentifiable nomen dubium.[5]

Because of its derived and specialized morphology, the relationships of Seorsumuscardinus are obscure. However, it shows some similarities with Muscardinus, a genus which includes the living hazel dormouse, and may share a common ancestor with it, such as the earlier fossil genus Glirudinus.[6] All three are part of the dormouse family, which includes many extinct forms dating back to the early Eocene (around 50 million years ago), as well as a smaller array of living species.[7] The generic name Seorsumuscardinus combines the Latin seorsum, which means "different", with Muscardinus and the specific name alpinus refers to the occurrence of S. alpinus close to the Alps. Heissigia honored paleontologist Kurt Heissig for his work in Bavaria on the occasion of his 65th birthday[8] and bolligeri honors Thomas Bolliger for his early description of material of this dormouse.[9]

Description

| Tooth | Measurement | Affalterbach | Oberdorf |

|---|---|---|---|

| P4 | Length | 1.03 | 0.93–0.97 |

| Width | 1.07 | 1.06–11.2 | |

| M1 | Length | 1.26 | 1.20–1.29 |

| Width | 1.40 | 1.31–1.43 | |

| M2 | Length | 1.14–1.22 | 1.21–1.24 |

| Width | 1.37–1.50 | 1.33–1.45 | |

| M3 | Length | 1.05 | 1.03 |

| Width | 1.25 | 1.19 | |

| p4 | Length | – | 0.80 |

| Width | – | 0.65 | |

| m1 | Length | 1.35 | 1.25–1.27 |

| Width | 1.28 | 1.26–1.31 | |

| m2 | Length | 1.28 | – |

| Width | 1.40 | – | |

| m3 | Length | – | 1.15–1.28 |

| Width | – | 1.06–1.27 | |

| All measurements are in millimeters. P4: fourth upper premolar; M1: first upper molar; etc. p4: fourth lower premolar; m1: first lower molar; etc. | |||

Only the cheek teeth of Seorsumuscardinus are known; these include the fourth premolar and three molars in the upper (maxilla) and lower jaws (mandible).[11] The teeth are medium-sized for a dormouse and have a flat occlusal (chewing) surface.[12] S. bolligeri is slightly larger than S. alpinus.[4]

Upper dentition

The fourth upper premolar (P4) has four main, transversely placed crests;[10] the description of S. bolligeri mentions an additional, centrally placed small crest.[9] De Bruijn interpreted the four main crests as the anteroloph, protoloph, metaloph, and posteroloph from front to back and wrote that these crests are not connected on the sides of the tooth.[13] Prieto and Böhme note that the posteroloph is convex on the back margin of the tooth.[9] In Muscardinus, the number of ridges on P4 ranges from five in Muscardinus sansaniensis to two in M. pliocaenicus and the living hazel dormouse, but the protoloph and metaloph are always connected on the lingual (inner) side of the tooth.[13] P4 is two-rooted in S. alpinus[13] and three-rooted in S. bolligeri.[9]

The first upper molar (M1) was described as square by De Bruijn[14] and as rounded by Prieto and Böhme.[9] There are five main transverse crests,[10] which are mostly isolated, but some may be connected on the borders of the teeth.[15] The middle crest, the centroloph, reaches to the labial (outer) margin in the single known M1 of S. bolligeri, but does not in any of the five M1 of S. alpinus.[16] The front crest, the anteroloph, is less distinct in S. bolligeri than most S. alpinus, but one M1 of S. alpinus is similar to that of S. bolligeri.[4] M1 has three roots in S. alpinus,[13] but the number of roots in S. bolligeri is not known.[17]

Prieto and Böhme describe M2 as less rounded than M1[17] and De Bruijn notes that the crests are more parallel.[18] In addition to the five main crests, small crests are present in front of and behind the centroloph that do not cover the full width of the tooth.[19] In one S. bolligeri M2, there is a small crest on the lingual side in front of the centroloph, but such a crest does not occur in any S. alpinus.[16] Another M2 of S. bolligeri has this crest on the labial side.[17] On the other hand, all five M2 of S. alpinus have a minor crest on the labial side behind the centroloph. In two M2 of S. alpinus, the centroloph and the metaloph are connected by a longitudinal crest, which is never present in S. bolligeri.[16] There are three roots.[20]

M3 is known from a single specimen each from Oberdorf, Affalterbach, and Tägernaustrasse.[21] In addition to the main crests, there are two or three additional smaller crests.[19] The roots are unknown.[17]

Lower dentition

The fourth lower premolar (p4) is known from a poorly preserved specimen from Oberdorf and a less worn specimen from Tägernaustrasse. There are four ridges, of which the front and back pair are connected at the lingual side and in the Oberdorf specimen also at the labial side. This tooth is similar to that of Muscardinus hispanicus, but the front pair is better developed.[18] There is one root.[13]

The first lower molar (m1) bears four main crests and a smaller one between the two crests at the back.[22] An additional crest (the anterotropid) is present between the two front crests, the anterolophid and the metalophid, in S. alpinus, but not in S. bolligeri.[16] The occlusal pattern of m2 resembles that of m1.[22] S. bolligeri also lacks an anterotropid on m2,[16] but the tooth is not known from Oberdorf.[18] In a worn m2 from Tägernaustrasse, there is a thickened portion in the labial part of the anterolophid, which Prieto interpreted as a remnant of the anterotropid; this led him to identify the Tägernaustrasse population as S. cf. alpinus.[4] Only Oberdorf has yielded the m3 of Seorsumuscardinus. It resembles the m1 and has a short anterotropid, but has more oblique crests.[18] In S. alpinus, the lower molars have two and occasionally three roots.[13] The roots of the m1 of S. bolligeri are not preserved and the m2 has two roots.[9]

Range

In MN 4, Seorsumuscardinus has been recorded from Oberdorf, Austria (sites 3 and 4, which yielded 6 and 17 Seorsumuscardinus alpinus teeth, respectively); Karydia, Greece (S. alpinus); and Tägernaustrasse, Switzerland (5 teeth; S. cf. alpinus). Affalterbach, Germany, where 10 teeth of S. bolligeri were found, is the only known MN 5 locality.[23] In all these localities, it is part of a diverse dormouse fauna.[24] Because the distributions of the two known species are temporally distinct, Prieto suggested that the genus may be useful for biostratigraphy (the use of fossils to determine the age of deposits).[4] Seorsumuscardinus occurred at the same time as the oldest known Muscardinus.[25]

References

- ↑ Bolliger, 1992, p. 129

- ↑ De Bruijn, 1998, pp. 111–113; Prieto, 2009, pp. 377, 379; Doukas, 2003, table 2

- ↑ Prieto and Böhme, 2007, pp. 303, 305; Prieto, 2009, p. 377

- 1 2 3 4 5 Prieto, 2009, p. 378

- ↑ Prieto, 2009, p. 379

- ↑ Prieto and Böhme, 2007, p. 306; Prieto, 2009, p. 378

- ↑ McKenna and Bell, 1997, pp. 174–178

- ↑ Prieto and Böhme, 2007, p. 302

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Prieto and Böhme, 2007, p. 303

- 1 2 3 De Bruijn, 1998, p. 112; Prieto and Böhme, 2007, p. 303

- ↑ De Bruijn, 1998, p. 110; Prieto and Böhme, 2007, p. 303

- ↑ Bolliger, 1992, p. 129; De Bruijn, 1998, p. 111; Prieto and Böhme, 2007, p. 303

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 De Bruijn, 1998, p. 112

- ↑ De Bruijn, 1998, p. 111

- ↑ De Bruijn, 1998, pp. 111–113; Prieto and Böhme, 2007, pp. 303–304

- 1 2 3 4 5 Prieto, 2009, p. 377

- 1 2 3 4 Prieto and Böhme, 2007, p. 304

- 1 2 3 4 De Bruijn, 1998, p. 113

- 1 2 De Bruijn, 1998, p. 113; Prieto and Böhme, 2007, p. 304

- ↑ De Bruijn, 1998, p. 112; Prieto and Böhme, 2007, p. 304

- ↑ De Bruijn, 1998, p. 112; Prieto and Böhme, 2007, p. 303; Bolliger, 1992, p. 129

- 1 2 De Bruijn, 1998, p. 113; Prieto and Böhme, 2007, p. 303

- ↑ Prieto, 2009; Bolliger, 1992, p. 128; De Bruijn, 1998, p. 112; Prieto and Böhme, 2007, p. 303

- ↑ Bolliger, 1992; De Bruijn, 1998; Doukas, 2003; Prieto and Böhme, 2007

- ↑ Prieto and Böhme, 2007, pp. 305–306

Literature cited

- Bolliger, T. 1992. Kleinsäuger aus der Miozänmolasse der Ostschweiz. Documenta Naturae 75:1–296.

- Bruijn, H. de. 1998. Vertebrates from the Early Miocene lignite deposits of the opencast mine Oberdorf (Western Styrian Basin, Austria): 6. Rodentia I (Mammalia). Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien 99A:99–137.

- Doukas, C.S. 2003. The MN4 faunas of Aliveri and Karydia (Greece). Coloquios de Paleontología, Volúmen Extraordinario 1:127–132.

- McKenna, M.C. and Bell, S.K. 1997. Classification of Mammals: Above the species level. New York: Columbia University Press, 631 pp. ISBN 978-0-231-11013-6

- Prieto, J. 2009. Comparison of the dormice (Gliridae, Mammalia) Seorsumuscardinus alpinus De Bruijn, 1998 and Heissigia bolligeri Prieto & Böhme, 2007 (subscription required). Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 252(3):377–379.

- Prieto, J. and Böhme, M. 2007. Heissigia bolligeri gen. et sp. nov.: a new enigmatic dormouse (Gliridae, Rodentia) from the Miocene of the Northern Alpine Foreland Basin (subscription required). Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 245(3):301–307.