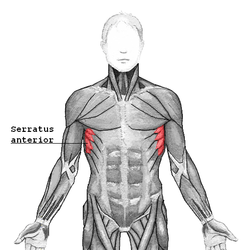

Serratus anterior muscle

| Serratus anterior | |

|---|---|

Serratus anterior, showing origin from lower ribs (origin from upper ribs obscured by pectoralis major and other superficial muscles) | |

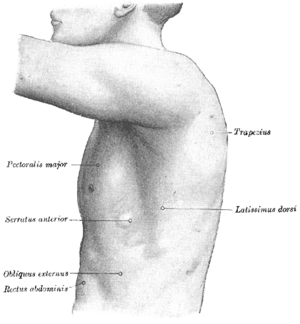

The left side of the thorax. | |

| Details | |

| Origin | fleshy slips from the outer surface of upper 8 or 9 ribs |

| Insertion | costal aspect of medial margin of the scapula |

| Artery | lateral thoracic artery (upper part), thoracodorsal artery (lower part) |

| Nerve | long thoracic nerve (from roots of brachial plexus C5, 6, 7) |

| Actions | protracts and stabilizes scapula, assists in upward rotation. |

| Antagonist | Rhomboid major, Rhomboid minor, Trapezius |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | musculus serratus anterior, serratus lateralis |

| TA | A04.4.01.008 |

| FMA | 13397 |

The serratus anterior (/ˌsᵻˈreɪtəs ænˈtɪəri.ər/) (Latin: serrare = to saw, referring to the shape, anterior = on the front side of the body) is a muscle that originates on the surface of the 1st to 8th ribs at the side of the chest and inserts along the entire anterior length of the medial border of the scapula.

Structure

Serratus anterior normally originates by nine or ten slips (muscle branches) from either the first to ninth ribs or the first to eighth ribs. Because two slips usually arise from the second rib, the number of slips is greater than the number of ribs from which they originate.[1]

The muscle is inserted along the medial border of the scapula between the superior and inferior angles along with being inserted along the thoracic vertebrae. The muscle is divided into three named parts depending on their points of insertions:[1]

- the serratus anterior superior is inserted near the superior angle

- the serratus anterior intermediate is inserted along the medial border

- the serratus anterior inferior is inserted near the inferior angle.

Relations

The serratus anterior lies deep to the subscapularis, from which it is separated by the subscapularis (supraserratus) bursa.[2] It is separated from the rib by the scapulothoracic (infraserratus) bursa.[3]

Innervation

The serratus anterior is innervated by the long thoracic nerve (Nerve of Bell), a branch of the brachial plexus. The long thoracic nerve travels inferiorly on the surface of the serratus. The nerve is especially vulnerable during certain types of surgery (for example, during lymph node clearance from the axilla (e.g., in case of axillary dissection in a surgery for breast cancer)). Damage to this nerve can lead to a winged scapula.

Function

All three parts described above pull the scapula forward around the thorax, which is essential for anteversion of the arm. As such, the muscle is an antagonist to the rhomboids. However, when the inferior and superior parts act together, they keep the scapula pressed against the thorax together with the rhomboids and therefore these parts also act as synergists to the rhomboids. The inferior part can pull the lower end of the scapula laterally and forward and thus rotates the scapula to make elevation of the arm possible. Additionally, all three parts can lift the ribs when the shoulder girdle is fixed, and thus assist in respiration.[1]

The serratus anterior is occasionally called the "big swing muscle" or "boxer's muscle" because it is largely responsible for the protraction of the scapula — that is, the pulling of the scapula forward and around the rib cage that occurs when someone throws a punch.

The serratus anterior also plays an important role in the upward rotation of the scapula, such as when lifting a weight overhead. It performs this in sync with the upper and lower fibers of the trapezius.[4]

Other animals

The muscles of the shoulder can be categorized into three topographic units: the scapulohumeral, axiohumeral, and axioscapular groups. Serratus anterior forms part of the latter group together with rhomboid major, rhomboid minor, levator scapulae, and trapezius. The trapezius evolved separately, but the other three muscles in this group evolved from the first eight or ten ribs and the transverse processes of the cervical vertebrae (homologous to the ribs).[5]

Functional demands have resulted in the evolution of individual muscles from the basal unit formed by the serratus anterior. In primitive life forms, the main function of the axioscapular group is to control the movements of the vertebral border of the scapula: fibers concerned with the dorsal movement of scapula evolved into the rhomboids, those with ventral motion into serratus anterior, and those with cranial movements into levator scapulae. The evolution of the serratus anterior itself has resulted in (1) grouping of its distal and proximal fibers, (2) size reduction of its intermediate fibers, and (3) the insertion of its dominant superior and inferior parts onto the superior and inferior angles of the scapula.[5]

In primates, the thoracic cage is wide and the scapula is rotated onto its posterior side to have the glenoid cavity face laterally. Additionally, the clavicle takes care of medial forces. In cursorial mammals (for example the horse and other quadrupeds), the scapula is hanging vertically on the side of the thorax and the clavicle is absent. Therefore, in climbing animals, the serratus anterior supports the scapula against the reaction forces of the free limb and exerts high bending forces on the ribs. To sustain these forces, the ribs have a pronounced curvature and are supported by the clavicle. In cursorial animals, the thorax is hanging between the scapulae at the serratus anterior and pectoralis muscles.[6]

Additional images

|

See also

- Pectoralis minor muscle

- Serratus posterior inferior muscle

- Serratus posterior superior muscle

- Backpack palsy

Notes

- 1 2 3 Platzer 2004, p. 144

- ↑ Giuseppe Milano; Andrea Grasso (16 December 2013). Shoulder Arthroscopy: Principles and Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 549–. ISBN 978-1-4471-5427-3.

- ↑ Giuseppe Milano; Andrea Grasso (16 December 2013). Shoulder Arthroscopy: Principles and Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 551–. ISBN 978-1-4471-5427-3.

- ↑ For Strong Healthy Shoulders, Functional Anatomy Surrounding the Scapulae by Bill Hartman and Mike Robertson.

- 1 2 Brand 2008, pp. 540–41

- ↑ Preuschoft 2004, pp. 369–72

References

- Brand, R. A. (2008). "Origin and Comparative Anatomy of the Pectoral Limb". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 466 (3): 531–42. doi:10.1007/s11999-007-0102-6. PMC 2505211

. PMID 18264841.

. PMID 18264841. - Platzer, Werner (2004). Color Atlas of Human Anatomy, Vol. 1: Locomotor System (5th ed.). Thieme. ISBN 3-13-533305-1.

- Preuschoft, H. (2004). "Mechanisms for the acquisition of habitual bipedality: are there biomechanical reasons for the acquisition of upright bipedal posture?". Journal of Anatomy. 204 (5): 363–84. doi:10.1111/j.0021-8782.2004.00303.x. PMC 1571303

. PMID 15198701.

. PMID 15198701.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Serratus anterior muscles. |

- 315621454 at GPnotebook

- Serratus_anterior at the Duke University Health System's Orthopedics program

- Anatomy figure: 04:03-06 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center – "Superficial muscles of the anterior chest wall."

- Anatomy figure: 05:02-07 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center – "Schematic illustration of a transverse section through the axilla."

- Anatomy diagram: 25466.098-1 at Roche Lexicon - illustrated navigator, Elsevier