Sharaku

Tōshūsai Sharaku (Japanese: 東洲斎 写楽; active 1794–1795) was a Japanese ukiyo-e print designer, known for his portraits of kabuki actors. Neither his true name nor the dates of his birth or death are known. His active career as a woodblock artist spanned ten months; his prolific work met disapproval and his output came to an end as suddenly and mysteriously as it had begun. His work has come to be considered some of the greatest in the ukiyo-e genre.

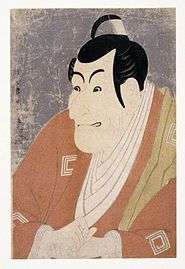

Primarily portraits of kabuki actors, Sharaku's compositions emphasize poses of dynamism and energy, and display a realism unusual for prints of the time—contemporaries such as Utamaro represented their subjects with an idealized beauty, while Sharaku did not shy from showing unflattering details. This was not to the tastes of the public, and the enigmatic artist's production ceased in the first month of 1795. His mastery of the medium with no apparent apprenticeship has drawn much speculation, and researchers have long attempted to discover his true identity—some suggesting he was an obscure poet, others a Noh actor, or even the ukiyo-e master Hokusai.

Works

Over 140 prints have been established as the work of Sharaku; the majority are portraits of actors or scenes from kabuki theatre, and most of the rest are of sumo wrestlers or warriors.[1] Energy and dynamism are the primary features of Sharaku's portraits, rather than the idealized beauty typical of ukiyo-e[2]—Sharaku highlights unflattering features such as large noses or the wrinkles of aging actors.[3]

In his actor prints Sharaku usually depicts a single figure with a focus on facial expression.[4] To Muneshige Narazaki Sharaku was able "to depict, within a single print, two or three levels of character revealed in the single moment of action forming the climax to a scene or performance".[5] Occasionally two figures appear, revealing a contrast of types, as of different facial shapes, or a beautiful face contrasted with one more plain.[4]

Sharaku shows the skill of a master, despite scant evidence that he had prior experience designing prints. To Jack Ronald Hillier, there are occasional signs of Sharaku struggling with his medium. Hillier compares Sharaku to French painter Paul Cézanne, who he believes "has to struggle to express himself, hampered and angered by the limitations of his draughtsmanship".[6]

The prints appeared in the common print sizes aiban, hosoban, and ōban.[lower-alpha 1] They are divided into four periods:[7]

- fifth month of 1794 — 28 ōban prints

- seventh and eight months of 1794 — 8 ōban and 30 hosoban prints

- eleventh month of 1794 — 47 hosoban, 13 aiban, and 4 ōban prints

- first month of 1795 — 10 hosoban and 5 aiban prints

The prints of the first two periods are signed "Tōshūsai Sharaku", the latter two only "Sharaku". The print sizes became progressively smaller and the focus shifts from busts to full-length portraits. The depictions become less expressive and more conventional.[4] Two picture calendars dating to as early as 1789 and three decorated fans as late as 1803 have been attributed to Sharaku, but have yet to be accepted as authentic works of his.[2] Sharaku's reputation rests largely on the earlier prints; those from the eleventh month of 1794 and after are considered artistically inferior.[1]

- Kabuki portraits by Sharaku

-

Ōtani Oniji III as Yakko Edobei

-

Ichikawa Yaozo III as Tanabe Bunzo

-

Sawamura Sōjurō III as Ogishi Kurando

-

Sakata Hangoro III as the villain Fujikawa Mizuemon

-

Segawa Kikujurō III as Oshizu, Wife of Tanabe

-

Ichikawa Ebizo IV as Takemura Sadanoshin

Identity

Biographers have long searched, but have had no luck in shining light on the identity of Sharaku.[8] The popularity the prints have attained feeds interest in the mystery, which in turns contributes further to interest the prints.[9] Of the more than fifty theories proposed,[10] few have been taken seriously, and none has found wide acceptance.[11]

A book on haiku theory and aesthetics from 1776 includes two poems attributed to a Sharaku, and references to a Nara poet by the same name appear in a 1776 manuscript and a 1794 poetry collection. No evidence aside from proximity in time has established a connection with the artist Sharaku.[12] A Shinto document of 1790 records the name Katayama Sharaku as husband of a disciple of the sect in Osaka. No further information is known of either the disciple or her husband.[13] A resemblance of Sharaku's kinetic kabuki portraits to those of Osaka-based contemporaries Ryūkōsai and Nichōsai has further fueled the idea of an Osaka-area origin.[14]

Rare calendar prints from 1789 and 1790 that bear the pseudonym "Sharakusai" have surfaced; that they may have been by Sharaku has not been dismissed, but they bear little obvious stylistic resemblance to Sharaku's identified work.[15]

Though disputed, Sharaku's prints have been said to resemble the masks of Noh theatre;[2] connections have been deduced from numerous documents that suggest to some researchers that Sharaku was a Noh actor serving under the lord of Awa Province, in modern Tokushima Prefecture. Amongst these documents are those that suggest Sharaku died between 1804 and 1807, including a Meiji-era manuscript that specifies the seventeenth day of the fifth month of 1806, and that his grave was marked in Kaizenji Temple in Asakusa in Edo.[16] Other similar theories, some discredited, include those that Sharaku was Noh actor Saitō Jūrōbei,[lower-alpha 2] Harutō Jizaemon,[lower-alpha 3] or Harutō Matazaemon.[lower-alpha 4][4]

In 1968[17] Tetsuji Yura proposed that Sharaku was Hokusai. The claim is also found in the Ukiyo-e Ruikō, and Sharaku's prints came during an alleged period of reduced productivity for Hokusai.[18] Though known primarily for his landscapes of the 19th century[19] before Sharaku's arrival Hokusai produced over a hundred actor portraits—an output that ceased in 1794.[18] Hokusai changed his art name dozens of times throughout his long career—government censorship under the Kansei Reforms[lower-alpha 5] may have motivated him to choose a name to distance his actor portraits from his other work.[20] As ukiyo-e artists normally do not carve their own woodblocks, a change in carver could explain differences in line quality.[21]

Others proposed identities include Sharaku's publisher Tsutaya or Tsutaya's father-in-law; the artists Utamaro, Torii Kiyomasa, Utagawa Toyokuni, or Maruyama Ōkyo; the painter-poet Tani Bunchō; the writer Tani Sogai; an unnamed Dutch artist; or actually three people.[22]

Reception and legacy

The Edo public reacted poorly to Sharaku's portraits. Contemporaries such as Utamaro who also worked in a relatively realistic style presented their subjects in a positive, beautifying way. Sharaku did not avoid depicting less flattering aspects of his subjects—he was the "arch-purveyor of vulgarities" to 19th-century art historian Ernest Fenollosa. An inscription on Utamaro's portrait of 1803 appears to target criticism at Sharaku's approach;[23] appearing eight years after Sharaku's supposed disappearance suggests that Sharaku's presence was still somehow felt, despite his lack of acceptance.[24]

On a decorated kite illustrated in Jippensha Ikku's book Shotōzan Tenarai Hōjō (1796) appears Sharaku's depiction of kabuki actor Ichikawa Ebizō IV; the accompanying text is filled with puns, jargon, and double entendres that have invited interpretation as commentary on the decline of Sharaku's later works and events surrounding his departure from the ukiyo-e world,[25] including speculation that he had been arrested and imprisoned.[20] Ikku published under Sharaku's publisher Tsutaya Jūzaburō from late 1794, and the book is the earliest to mention Sharaku.[25] The Ukiyo-e Ruikō, the oldest surviving work on ukiyo-e, contains the oldest direct comment on Sharaku's work:[26]

"Sharaku designed likenesses of kabuki actors, but because he depicted them too truthfully, his prints do not conform to accepted ideas, and his career was short, ending after about a year."[lower-alpha 6]

The Ukiyo-e Ruikō was not a published book, but a manuscript that was hand-copied over generations, with great variations in content, some of which has fueled speculation as to Sharaku's identity.[27] including a version[lower-alpha 7] that calls Sharaku "Hokusai II".[28] Shikitei Sanba wrote in 1802 of ukiyo-e artists, and included an illustration of active and inactive artists and their schools as a map; Sharaku appears as an inactive artist depicted as a solitary island with no followers.[11] Essayist Katō Eibian wrote in the early 19th century that Sharaku "should be praised for his elegance and strength of line".[11]

Sharaku's work was popular among European collectors,[29] but rarely received mention in print until German collector Julius Kurth's book Sharaku appeared in 1910.[4] Kurth ranked Sharaku's portraits with those of Rembrandt and Velázquez,[30] and asserted Sharaku was Noh actor Saitō Jūrōbei.[4] The book ignited international interest in the artist, resulting in a reevaluation that has placed Sharaku amongst the greatest ukiyo-e masters.[31] The first in-depth work on Sharaku was Harold Gould Henderson and Louis Vernon Ledoux's The Surviving Works of Sharaku in 1939.[30] Certain portraits such as Ōtani Oniji III are particularly well known.[32]

Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein believed that objective realism was not the only valid means of expression. He found Sharaku "repudiated normalcy"[33] and departed from strict realism and anatomical proportions to achieve exppressive, emotional effects.[34]

1983 saw the appearance of the novels Phantom Sharaku by Akiko Sugimoto—a novel whose protagonist is Tsutaya[35]—and The Case of the Sharaku Murders by Katsuhiko Takahashi.[36] In 1995 Masahiro Shinoda directed a fictionalized film of Sharaku's career, Sharaku.[37]

Notes

- ↑ The approximate dimensions of these sizes are:[1]

- aiban — 23 by 33 centimetres (9.1 in × 13.0 in)

- hosoban — 15 by 33 centimetres (5.9 in × 13.0 in)

- ōban — 25 by 36 centimetres (9.8 in × 14.2 in)

- ↑ 斎藤 十郎兵衛 Saitō Jūrōbei

- ↑ 春藤 次左衛門 Harutō Jizaemon

- ↑ 春藤 又左衛門 Harutō Matazaemon

- ↑ The Kansei Reforms put restrictions with severe penalties on luxurious displays by the common people. Tsutaya's publication of an Utamaro portrait of a woman printed with mica in the background ink was considered too opulent, and Tsutaya had half his fortune seized. Penalties for other publishers included the confiscation or destruction of their printing blocks.[20]

- ↑ 「これは歌舞伎役者の似顔をうつせしが、あまり真を画かんとて、あらぬさまにかきなせしば長く世に行われず一両年にて止む」

- ↑ The Kazayamabon Ukiyo-e Ruikō of 1822[28]

References

- 1 2 3 Narazaki 1994, p. 89.

- 1 2 3 Narazaki 1994, p. 74.

- ↑ Tanaka 1999, p. 165.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kondō 1955.

- ↑ Narazaki 1994, p. 75.

- ↑ Hillier 1954, p. 23.

- ↑ Narazaki 1994, p. 89; Tanaka 1999, p. 159.

- ↑ Narazaki 1994, pp. 67, 76.

- ↑ Nakano 2007, pp. ii, iv.

- ↑ Nakano 2007, p. ii.

- 1 2 3 Narazaki 1994, p. 76.

- ↑ Narazaki 1994, p. 77.

- ↑ Narazaki 1994, pp. 77–78.

- ↑ Narazaki 1994, p. 78.

- ↑ Narazaki 1994, p. 78–79.

- ↑ Narazaki 1994, pp. 85–86.

- ↑ Tanaka 1999, p. 189.

- 1 2 Tanaka 1999, p. 164.

- ↑ Tanaka 1999, pp. 187–188.

- 1 2 3 Tanaka 1999, p. 179.

- ↑ Tanaka 1999, p. 166.

- ↑ Nakano 2007, p. iii.

- ↑ Narazaki 1994, pp. 74, 85–86.

- ↑ Narazaki 1994, p. 86.

- 1 2 Narazaki 1994, pp. 83–85.

- ↑ Narazaki 1994, p. 85.

- ↑ Narazaki 1994, pp. 83–85; Tanaka 1999, p. 184.

- 1 2 Tanaka 1999, p. 184.

- ↑ Hockley 2003, p. 3.

- 1 2 Münsterberg 1982, p. 101.

- ↑ Hendricks 2011.

- ↑ Tanaka 1999, p. 174.

- ↑ Fabe 2004, p. 198.

- ↑ Fabe 2004, pp. 197–198.

- ↑ Schierbeck & Edelstein 1994, p. 290.

- ↑ Lee 2014.

- ↑ Crow 2010.

Works cited

- Crow, Jonathan (2010). "Sharaku (1995)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2013-11-13. Retrieved 2015-01-21.

- Fabe, Marilyn (2004). Closely Watched Films: An Introduction to the Art of Narrative Film Technique. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-93729-1.

- Hendricks, Jim (2011-02-26). "Expressions of a Master". Albany Herald. Retrieved 2015-01-21.

- Hillier, Jack Ronald (1954). Japanese Masters of the Colour Print: A Great Heritage of Oriental Art. Phaidon Press. OCLC 1439680.

- Hockley, Allen (2003). The Prints of Isoda Koryūsai: Floating World Culture and Its Consumers in Eighteenth-century Japan. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98301-1.

- Kondō, Ichitarō (1955). Toshusai Sharaku. Tuttle Publishing. (pages unnumbered)

- Lee, Andrew (2014-06-21). "The Case of the Sharaku Murders". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 2014-06-27. Retrieved 2015-01-21.

- Münsterberg, Hugo (1982). The Japanese Print: A Historical Guide. Weatherhill. ISBN 978-0-8348-0167-7.

- Nakano, Mitsutoshi (2007). Sharaku: Edojin to shite no jituzō 写楽: 江戸人としての実像 [Sharaku: True portrait as an Edoite] (in Japanese). Chūōkōron. ISBN 978-4-12-101-886-1.

- Narazaki, Muneshige (1994). Sharaku: The Enigmatic Ukiyo-e Master. Translated by Bonnie F. Abiko. Kodansha America. ISBN 978-4-7700-1910-3.

- Schierbeck, Sachiko Shibata; Edelstein, Marlene R. (1994). Japanese Women Novelists in the 20th Century: 104 Biographies, 1900–1993. Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 978-87-7289-268-9.

- Tanaka, Hidemichi (1999). "Sharaku Is Hokusai: On Warrior Prints and Shunrô's (Hokusai's) Actor Prints". Artibus et Historiae. IRSA. 20 (39): 157–190. JSTOR 1483579.

Further reading

- Henderson, Harold Gould; Ledoux, Louis Vernon (1939). The Surviving Works of Sharaku. Weyhe.

- Henderson, Harold Gould; Ledoux, Louis Vernon (1984). Sharaku's Japanese Theatre Prints: An Illustrated Guide to his Complete Work. Dover Publications.

- Kurth, Julius (1910). Sharaku. R. Piper & Company.

- Nakashima, Osamu (2012). Tōshūsai Sharaku kōshō 「東洲斎写楽」考証 [Historical investigation into Tōshūsai Sharaku]. Sairyūsha. ISBN 978-4-7791-1806-7.

- Suzuki, Jūzō (1968). Sharaku. Kodansha International. ISBN 978-0-87011-056-6.

- Uchida, Chizuko (2007). Sharaku wo oe: Tensai eshi ha naze kieta no ka 写楽を追え: 天才絵師はなぜ消えたのか [In pursuit of Sharaku: Why did this genius artist disappear?]. East Press. ISBN 978-4-87257-755-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tōshūsai Sharaku. |

_Ichikawa_Ebiz%C5%8D_as_the_Saint_Monkaku_Disguised_as_a_Bandit.jpg)