Split of early Christianity and Judaism

The split of early Christianity and Judaism took place during the first centuries of the Common Era. It is commonly attributed to a number of events, including the rejection and crucifixion of Jesus (c. 33), the Council of Jerusalem (c. 50), the destruction of the Second Temple and institution of the Jewish tax in 70, the postulated, and largely discredited, Council of Jamnia c. 90, and the Bar Kokhba revolt of 132–135.

While it is commonly believed that Paul the Apostle established a primarily Gentile church within his lifetime, it took centuries for a complete break with Judaism to manifest, and the relationship between Paul and Second Temple Judaism is still disputed with a wide range of views.

Competing views

The traditional view has been that Judaism existed before Christianity and that Christianity separated from Judaism some time after the destruction of the Second Temple. Recently, some scholars have argued that there were many competing Jewish sects in the Holy Land during the Second Temple period, and that those that became Rabbinic Judaism and Proto-orthodox Christianity were but two of these. Some of these scholars have proposed a model which envisions a twin birth of Proto-orthodox Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism rather than a separation of the former from the latter. For example, Robert Goldenberg asserts that it is increasingly accepted among scholars that "at the end of the 1st century AD there were not yet two separate religions called 'Judaism' and 'Christianity'".[1]

Daniel Boyarin proposes a revised understanding of the interactions between nascent Christianity and Judaism in late antiquity, viewing the two "new" religions as intensely and complexly intertwined throughout this period. Boyarin writes: "for at least the first three centuries of their common lives, Judaism in all of its forms and Christianity in all of its forms were part of one complex religious family, twins in a womb, contending with each other for identity and precedence, but sharing with each other the same spiritual food".[2]

Without the power of the orthodox Church and the Rabbis to declare people heretics and outside the system it remained impossible to declare phenomenologically who was a Jew and who was a Christian. At least as interesting and significant, it seems more and more clear that it is frequently impossible to tell a Jewish text from a Christian text. The borders are fuzzy, and this has consequences. Religious ideas and innovations can cross borders in both directions.[3]

Philip S. Alexander characterizes the question of when Christianity and Judaism parted company and went their separate ways as "one of those deceptively simple questions which should be approached with great care."[4]

Robert M. Price asserts the relative separateness of "classic," "Orthodox" Christianity and Javneh-Rabbinic Judaism.

Thus Christianity as we know it and Judaism as we know it never in fact separated from one another in the manner of, say, Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic Christianity in the eleventh century. Rather, each is a finally dominant form at the end of its own branch of the tree of religious evolution.[5]

It has been argued that few Jews joined the Christian movement in the first century and that the movement probably never exceeded 1,000 Jewish members at any one time during the first century. Furthermore, some argue that the size and importance of the Christian movement in general during the first century may be exaggerated; sociologist R. Stark, assuming a Christian population of 1,000 in the year 40 and a growth rate of 40 percent per decade until the year 300, concluded that at the end of the 1st century the total Christian population was only 7,530—though other scholars disagree with this analysis.[6]

Compatibility of Christianity with Second Temple Judaism

Jewish messianism

Judaism is known to allow for multiple messiahs; the two most relevant are Messiah ben Joseph and the traditional Messiah ben David. Some scholars have argued to varying degrees that Christianity and Judaism did not separate as suddenly or as dramatically as sometimes thought and that the idea of two messiahs, one suffering and the second fulfilling the traditional messianic role, was normative to ancient Judaism, in fact predating Jesus. Furthermore, Jesus would have been viewed as fulfilling this role.[7][8][9][10]

Alan Segal has written that "one can speak of a 'twin birth' of two new Judaisms, both markedly different from the religious systems that preceded them. Not only were rabbinic Judaism and Christianity religious twins, but, like Jacob and Esau, the twin sons of Isaac and Rebecca, they fought in the womb, setting the stage for life after the womb."[11]

For Martin Buber, Judaism and Christianity were variations on the same theme of messianism. Buber made this theme the basis of a famous definition of the tension between Judaism and Christianity:

Pre-messianically, our destinies are divided. Now to the Christian, the Jew is the incomprehensibly obdurate man who declines to see what has happened; and to the Jew, the Christian is the incomprehensibly daring man who affirms in an unredeemed world that its redemption has been accomplished. This is a gulf which no human power can bridge.[12]

Jewish messianism has its root in the apocalyptic literature of the 2nd century BCE to 1st century BCE, promising a future "anointed" leader or Messiah to resurrect the Israelite "Kingdom of God", in place of the foreign rulers of the time. This corresponded with the Maccabean Revolt directed against the Seleucids. Following the fall of the Hasmonean kingdom, it was directed against the Roman administration of Iudaea Province, which, according to Josephus, began with the formation of the Zealots during the Census of Quirinius of 6 CE, although full scale open revolt did not occur until the First Jewish–Roman War in 66 CE. Historian H. H. Ben-Sasson has proposed that the "Crisis under Caligula" (37–41) was the "first open break between Rome and the Jews", even though problems were already evident during the Census of Quirinius in 6 CE and under Sejanus (before 31).[13]

Judaism at this time was divided into antagonistic factions. The main camps were the Pharisees, Sadducees, and Zealots, but also included many other less influential sects (including the Essenes), see Second Temple Judaism for details. This led to further unrest, and the 1st century BCE and 1st century CE saw a number of charismatic religious leaders, contributing to what would become the Mishnah of Rabbinic Judaism, including Yochanan ben Zakai and Hanina Ben Dosa. The ministry of Jesus, according to the account of the Gospels, falls into this pattern of sectarian preachers with devoted disciples.

Christian understanding of Jesus as messiah

Paula Fredriksen, in From Jesus to Christ, has suggested that Jesus's impact on his followers was so great that they could not accept the failure implicit in his death. According to the New Testament, Jesus's followers reported that they encountered Jesus after his crucifixion; they argued that he had been resurrected (the belief in the resurrection of the dead in the messianic age was a core Pharisaic doctrine), and would soon return to usher in the Kingdom of God and fulfill the rest of Messianic prophecy such as the Resurrection of the dead and the Last Judgment. Others adopted Gnosticism as a way to maintain the vitality and validity of Jesus's teachings (see Elaine Pagels, The Gnostic Gospels). Since early Christians believed that Jesus had already replaced the Temple as the expression of a new covenant, they were relatively unconcerned with the destruction of the Temple, though it came to be viewed as symbolic to the doctrine of Supersessionism.

According to many historians, most of Jesus's teachings were intelligible and acceptable in terms of Second Temple Judaism; what set Christians apart from Jews was their faith in Christ as the resurrected messiah.[14] The belief in a resurrected Messiah is unacceptable to Jews today and to Rabbinic Judaism, and Jewish authorities have long used this fact to explain the break between Judaism and Christianity.

Recent work by historians paints a more complex portrait of late Second Temple Judaism and early Christianity. Some historians have suggested that, before his death, Jesus created amongst his believers such certainty that the Kingdom of God and the resurrection of the dead was at hand, that with few exceptions (John 20: 24-29) when they saw him shortly after his execution, they had no doubt that he had been resurrected, and that the restoration of the Kingdom and resurrecton of the dead was at hand. These specific beliefs were compatible with Second Temple Judaism.[15] In the following years the restoration of the Kingdom, as Jews expected it, failed to occur. Some Christians believed instead that Christ, rather than being the Jewish messiah, was God made flesh, who died for the sins of humanity, and that faith in Jesus Christ offered everlasting life (see Christology).[16]

Jewish rejection of Jesus as messiah

The first Christians (the disciples or students of Jesus) were essentially all ethnically Jewish or Jewish proselytes. In other words, Jesus was Jewish, preached to the Jewish people and called from them his first disciples. However, the Great Commission, issued after the Resurrection, is specifically directed at "all nations." Jewish Christians, as faithful religious Jews, regarded "Christianity" as an affirmation of every aspect of contemporary Judaism, with the addition of one extra belief—that Jesus was the Messiah.[17]

The doctrines of the apostles of Jesus brought the Early Church into conflict with some Jewish religious authorities (Acts records dispute over resurrection of the dead which was rejected by the Sadducees, see also Persecution of Christians in the New Testament), and possibly later led to Christians' expulsion from synagogues (see Council of Jamnia for other theories). While Marcionism rejected all Jewish influence on Christianity, Proto-orthodox Christianity instead retained some of the doctrines and practices of 1st-century Judaism while rejecting others, see the Historical background to the issue of Biblical law in Christianity and Early Christianity. They held the Jewish scriptures to be authoritative and sacred, employing mostly the Septuagint or Targum translations, and adding other texts as the New Testament canon developed. Christian baptism was another continuation of a Judaic practice.[18]

Conversion of Paul

Before his conversion, Paul persecuted the Jewish Christians as a heretical sect, such as the martyrdom of Stephen. After his conversion, he assumed the title of "Apostle to the Gentiles" and actively converted gentiles to his beliefs, known as Pauline Christianity. Paul's influence on Christian thinking arguably has been more significant than any other New Testament author.[19] Augustine (354-430) developed Paul's idea that salvation is based on faith and not "works of the law".[19] Luther (1483–1546) and his doctrine of sola fide were heavily influenced by Paul. Evangelical Christians refer to the Romans road, an explanation of the Gospel of Jesus Christ taken solely from the book of Romans, using esp. Romans 3:23 and Romans 6:23, which indicate, respectively, the need of each person for God's forgiveness and God's gift of that forgiveness through Jesus.

Recently, Talmudic scholar Daniel Boyarin has argued that Paul's theology of the spirit is more deeply rooted in Hellenistic Judaism than generally believed. In A Radical Jew, Boyarin argues that Paul combined the life of Jesus with Greek philosophy to reinterpret the Hebrew Bible in terms of the Platonic dualist opposition between the ideal (which is real) and the material (which is false).[20][21]

Possible conversion of Gamaliel

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia:

The Jewish accounts make him die a Pharisee, and state that: "When he died, the honour of the Torah (the law) ceased, and purity and piety became extinct". At an early date, ecclesiastical tradition has supposed that Gamaliel embraced the Christian Faith, and remained a member of the Sanhedrin for the purpose of helping secretly his fellow-Christians (cf. Recognitions of Clement, I, lxv, lxvi). According to Photius, he was baptized by St. Peter and St. John, together with his son and with Nicodemus. His body, miraculously discovered in the fifth century, is said to be preserved at Pisa, in Italy.[22]

Christian abandonment of Jewish practices

According to historian Shaye J.D. Cohen, early Christianity ceased to be a Jewish sect when it ceased to observe Jewish practices.[23] Among the Jewish practices abandoned by Proto-orthodox Christianity, circumcision was rejected as a requirement at the Council of Jerusalem, c. 50. The establishment of a Jewish Tax known as the fiscus Judaicus helped widen the gap between Christians and Jews for anyone that appeared to be Jewish was taxed after AD 70. Sabbath observance was modified, perhaps as early as Ignatius of Antioch (c.110).[24] Quartodecimanism (observation of a Paschal feast on Nisan 14, the day of preparation for Passover, linked to Polycarp and thus to John the Apostle) was disputed by Pope Victor I (189–199) and formally rejected at the First Council of Nicaea in 325.[25]

Council of Jerusalem

In or around the year 50, the apostles convened the first church council (although whether it was a council in the later sense is questioned), known as the Council of Jerusalem, to reconcile practical (and by implication doctrinal) differences concerning the Gentile mission.[26] At the Council of Jerusalem it was agreed that gentiles could be accepted as Christians without full adherence to the Mosaic Laws, possibly a major break between Christianity and Judaism, though the decree of the council (Acts 15:19–29) seems to parallel the Noahide laws of Judaism, which would make it a commonality rather than a difference. The Council of Jerusalem, according to Acts 15, determined that circumcision was not required of Gentile converts, only avoidance of "pollution of idols, fornication, things strangled, and blood" (Acts 15:20), possibly establishing nascent Christianity as an attractive alternative to Judaism for prospective Proselytes. Around the same time period, Judaism made its circumcision requirement of Jewish boys even stricter.[27]

According to the 19th-century Roman Catholic Bishop Karl Josef von Hefele, the Apostolic Decree of the Jerusalem Council "has been obsolete for centuries in the West", though it is still recognized and observed by the Greek Orthodox Church.[28] Acts 28 Hyperdispensationalists, such as the 20th-century Anglican E. W. Bullinger, would be another example of a group that believes the decree (and everything before Acts 28) no longer applies.

In addition, the Apostolic Age is particularly significant to Christian Restorationism which claims that it represents a purer form of Christianity that should be restored to the church as it exists today.

Emergence of Rabbinic Judaism and Christianity

At the time of the Destruction of the Second Temple, Judaism was divided into antagonistic factions. The main camps were the Pharisees, the Saducees, and the Zealots, but they also included other less influential sects. This led to further unrest, and the 1st centuries BC and AD both saw a number of charismatic religious leaders, contributing to what would become the Mishnah of Rabbinic Judaism, including Yochanan ben Zakai and Hanina Ben Dosa.

According to most scholars, the followers of Jesus were composed principally of apocalyptic Jewish sects during the late Second Temple period of the 1st century. Some Early Christian groups were strictly Jewish, such as the Ebionites and the early church leaders in Jerusalem, collectively called Jewish Christians. During this period, they were led by James the Just. Paul of Tarsus, commonly known as Saint Paul, persecuted the early Jewish Christians, then converted and adopted the title of "Apostle to the Gentiles" and started proselytizing among the Gentiles. He persuaded the leaders of the Jerusalem Church to allow Gentile converts exemption from most Jewish commandments at the Council of Jerusalem, which may parallel Noahide Law in Rabbinic Judaism.

Most historians agree that Jesus or his followers established a new Jewish sect, one that attracted both Jewish and Gentile converts. Historians continue to debate the precise moment when Christianity established itself as a new religion, apart and distinct from Judaism. Some scholars view Christians as much as Pharisees as being competing movements within Judaism that decisively broke only after the Bar Kokhba's revolt, when the successors of the Pharisees claimed hegemony over all Judaism, and – at least from the Jewish perspective – Christianity emerged as a new religion. Some Christians were still part of the Jewish community up until the time of the Bar Kochba revolt in the 130s, see also Jewish Christians.

According to historian Shaye J. D. Cohen,

The separation of Christianity from Judaism was a process, not an event. The essential part of this process was that the church was becoming more and more gentile, and less and less Jewish, but the separation manifested itself in different ways in each local community where Jews and Christians dwelt together. In some places, the Jews expelled the Christians; in other, the Christians left of their own accord.[29]

According to Cohen, this process ended in 70 CE, after the great revolt, when various Jewish sects disappeared and Pharisaic Judaism evolved into Rabbinic Judaism, and Christianity emerged as a distinct religion.[30]

The Great Revolt and the Destruction of the Temple

By AD 66 Jewish discontent with Rome had escalated. At first, the priests tried to suppress rebellion, even calling upon the Pharisees for help. After the Roman garrison failed to stop Hellenists from desecrating a synagogue in Caesarea, however, the high priest suspended payment of tribute, inaugurating the Great Jewish Revolt. According to a tradition recorded by Eusebius and Epiphanius, the Jerusalem church fled to Pella at the outbreak of the Great Jewish Revolt (66-70 AD) (see: Flight to Pella).[31]

After a Jewish revolt against Roman rule, the Romans all but destroyed Jerusalem. Following a second revolt, Jews were not allowed to enter the city of Jerusalem except for the day of Tisha B'Av and most Jewish worship was forbidden by Rome. Rome instituted the Fiscus Judaicus, those who paid the tax were allowed to continue Jewish practices. Following the destruction of Jerusalem and the expulsion of the Jews, Jewish worship stopped being centrally organized around the Temple, prayer took the place of sacrifice, and worship was rebuilt around rabbis who acted as teachers and leaders of individual communities (see Jewish diaspora and Council of Jamnia).

In AD 70 the Temple was destroyed. The destruction of the Second Temple was a profoundly traumatic experience for the Jews, who were now confronted with difficult and far-reaching questions:[32]

- How to achieve atonement without the Temple?

- How to explain the disastrous outcome of the rebellion?

- How to live in the post-Temple, Romanized world?

- How to connect present and past traditions?

How people answered these questioned depended largely on their position prior to the revolt. But the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans not only put an end to the revolt, it marked the end of an era. Revolutionaries like the Zealots had been crushed by the Romans, and had little credibility (the last Zealots died at Masada in 73). The Sadducees, whose teachings were so closely connected to the Temple cult, disappeared. The Essenes also vanished, perhaps because their teachings so diverged from the issues of the times that the destruction of the Second Temple was of no consequence to them; precisely for this reason, they were of little consequence to the vast majority of Jews.

Two organized groups remained: the Early Christians, and Pharisees. Some scholars, such as Daniel Boyarin and Paula Fredricksen, suggest that it was at this time, when Christians and Pharisees were competing for leadership of the Jewish people, that accounts of debates between Jesus and the apostles, debates with Pharisees, and anti-Pharisaic passages, were written and incorporated into the New Testament.

The Emergence of Rabbinic Judaism

During the 1st century CE, several Jewish sects were extant, including the Pharisees, the Sadducees, the Zealots, Essenes, and Christians. The Pharisees' teachings, which viewed halakha (Jewish law) as a means by which ordinary people could engage with the sacred in their daily lives, and provided them with a position from which they could respond to all four challenges in a way that was meaningful to the vast majority of Jews. The Sadducees rejected the divine inspiration of the Prophets and the Writings, relying only on the Torah as divinely inspired. Consequently, a number of other core tenets of the Pharisees' belief system, were also dismissed by the Sadducees.

After the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, sectarianism largely came to an end. Christianity survived, but broke with Judaism and became a separate religion; the Pharisees survived in the form of Rabbinic Judaism, today, known simply as "Judaism". During this period, Rome governed Judea through a Procurator at Caesarea and a Jewish Patriarch. A former leading Pharisee, Yohanan ben Zakkai, was appointed the first Patriarch (the Hebrew word, Nasi, also means prince, or president), and he reestablished the Sanhedrin at Jamnia under Pharisaic control. Instead of giving tithes to the priests and sacrificing offerings at the Temple, the rabbis instructed Jews to give money to charities and study in local synagogues, as well as to pay the Fiscus Judaicus.

In 132, the Emperor Hadrian threatened to rebuild Jerusalem as a pagan city dedicated to Jupiter, called Aelia Capitolina. Some of the leading sages of the Sanhedrin supported a rebellion (and, for a short time, an independent state) led by Simon bar Kozeba (also called Bar Kochba, or "son of a star"); some, such as Rabbi Akiva, believed Bar Kochbah to be messiah, or "anointed one". Up until this time, a number of Christians were still part of the Jewish community. However, they did not support or take part in the revolt. Whether because they had no wish to fight, or because they could not support a second messiah in addition to Jesus, or because of their harsh treatment by Bar Kochba during his brief reign, these Christians also left the Jewish community around this time.

This revolt ended in 135 when Bar Kochba and his army were defeated. According to a midrash, in addition to Bar Kochba the Romans tortured and executed ten leading members of the Sanhedrin. This account also claims this was belated repayment for the guilt of the ten brothers who kidnapped Joseph. It is possible that this account represents a Pharisaic response to the Christian account of Jesus' crucifixion; in both accounts the Romans brutally punish rebels, who accept their torture as atonement for the crimes of others.

After the suppression of the revolt the vast majority of Jews were sent into exile; shortly thereafter (around 200), Judah haNasi edited together judgements and traditions into an authoritative code, the Mishna. This marks the transformation of Pharisaic Judaism into Rabbinic Judaism.

Although the Rabbis traced their origins to the Pharisees, Rabbinic Judaism nevertheless involved a radical repudiation of certain elements of Pharisaism—elements that were basic to Second Temple Judaism. The Pharisees had been partisan. Members of different sects argued with one another over the correctness of their respective interpretations, most notably the sages Hillel and Shammai. After the destruction of the Second Temple, these sectarian divisions ended. The term "Pharisee" was no longer used, perhaps because it was a term more often used by non-Pharisees, but also because the term was explicitly sectarian. The Rabbis claimed leadership over all Jews, and added to the Amidah the Birkat haMinim (see Council of Jamnia), a prayer which in part exclaims, "Praised are You O Lord, who breaks enemies and defeats the arrogant," and which is understood as a rejection of sectarians and sectarianism. This shift by no means resolved conflicts over the interpretation of the Torah; rather, it relocated debates between sects to debates within Rabbinic Judaism.

As the Rabbis were required to face a new reality—mainly Judaism without a Temple (to serve as the center of teaching and study) and Judea without autonomy—there was a flurry of legal discourse and the old system of oral scholarship could not be maintained. It is during this period that Rabbinic discourse began to be recorded in writing.[33] The theory that the destruction of the Temple and subsequent upheaval led to the committing of Oral Law into writing was first explained in the Epistle of Sherira Gaon and often repeated.[34]

The oral law was subsequently codified in the Mishna and Gemarah, and is interpreted in Rabbinic literature detailing subsequent rabbinic decisions and writings. Rabbinic Jewish literature is predicated on the belief that the Written Law cannot be properly understood without recourse to the Oral Law (the Mishnah).

Much Rabbinic Jewish literature concerns specifying what behavior is sanctioned by the law; this body of interpretations is called halakha (the way).

The Emergence of Christianity

According to Shaye J.D. Cohen, Jesus's failure to establish an independent Israel, and his death at the hands of the Romans, caused many Jews to reject him as the Messiah (see for comparison: prophet and false prophet).[23] Christians who profess the Nicene Creed, which is the majority, believe that the "Kingdom of God" will be fully established at the Second Coming of Christ. In the aftermath of the destruction of the Temple, and then the defeat of Bar Kokhba, it is claimed that more Jews continued to be attracted to the Pharisaic rabbis than to Christianity, because they believed the latter to be a form of idolatry and thus antithetical to the unity of God as expressed in the Mosaic tradition (see Maimonides, Laws of King 11:4). Also, Jews at that time were expecting a military leader as a Messiah, such as Bar Kohhba. According to the majority of historians, Jesus' teachings were intelligible and acceptable in terms of Second Temple Judaism; what set Christians apart from Jews was their faith in Christ as the resurrected messiah.[14] The belief in a resurrected Messiah is said to be unacceptable to Jews who practice Rabbinic Judaism; Jewish authorities have long used this fact to explain the break between Judaism and Christianity. Recent work by historians paints a more complex portrait of late Second Temple Judaism and early Christianity. Some historians have suggested that, before his death, Jesus forged among his believers such certainty that the Kingdom of God and the resurrection of the dead was at hand, that with few exceptions (John 20: 24-29) when they saw him shortly after his execution, they had no doubt that he had been resurrected, and that the restoration of the Kingdom and resurrection of the dead was at hand, though only Full Preterism proposes that all this happened in the first century. These specific beliefs were compatible with Second Temple Judaism.[15] In the following years the restoration of the Kingdom as expected failed to occur. Some Christians believed instead that Christ, rather than being the Jewish messiah, was God made flesh, who died for the sins of humanity, and that faith in Jesus Christ offered everlasting life (see Christology).[16]

The foundation for this new interpretation of Jesus' crucifixion and resurrection are found in the epistles of Paul and in the book of Acts. Adherents to the modern form of Talmudic Judaism whose thinking is influenced by religious categories tend to view Paul as the founder of "Christianity." However, recently, Talmud scholar Daniel Boyarin has argued that Paul's theology of the spirit is more deeply rooted in Hellenistic Judaism than has been generally argued by proponents of modern Talmudic Judaism. In his work A Radical Jew, Boyarin argues that Paul of Tarsus combined the life of Jesus with Greek philosophy to interpret the Hebrew Bible in terms of the Platonic opposition between the ideal (which is real) and the material (which is false); see also Paul of Tarsus and Judaism. Judaism is a corporeal religion, in which membership is based not on belief but rather descent from Abraham, physically marked by circumcision, and focusing on how to live this life properly. According to Boyarin, Paul saw in the "symbol" of a resurrected Jesus the possibility of a spiritual rather than corporeal messiah. He used this notion of messiah, so Boyarin, to argue for a religion through which all people—not just descendants of Abraham—could worship the God of Abraham. Unlike Judaism, which holds that it is the proper religion only of the Jews, Pauline Christianity claimed to be the proper religion for all people.

In other words, by appealing to the Platonic distinction between the material and the ideal, Paul showed how the spirit of Christ could provide all people a way to worship God—the God who had previously been worshiped only by Jews, and Jewish Proselytes, although Jews claimed that He was the one and only God of all (see, for example, Romans 8: 1–4; II Corinthians 3:3; Galatians 3: 14; Philippians 3:3). Boyarin attempts to root Paul's work in Hellenistic Judaism and insists that Paul was thoroughly Jewish. But, Boyarin argues, Pauline theology made his version of Christianity so appealing to Gentiles. Nevertheless, Boyarin also sees this so-called Platonic reworking of both Jesus' teachings and Pharisaic Judaism as essential to the emergence of Christianity as a distinct religion, because it justified a Judaism without Jewish law (see also New Covenant).

The above events and trends led to a gradual split between Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism.[35][36] According to historian Shaye J.D. Cohen, "Early Christianity ceased to be a Jewish sect when it ceased to observe Jewish practices".[23] It has been argued that a significant contributing factor to the split was the two groups' differing theological interpretations of the Temple's destruction. Rabbinic Judaism saw the destruction as a chastisement for neglecting the Torah. The early Christians however saw it as God’s punishment for the Jewish rejection of Jesus, leading to the claim that the 'true' Israel was now the Church (see Supersessionism). Jews believed this claim was scandalous.[37]

Council of Jamnia

A hypothetical Council of Jamnia circa 85 is often stated to have condemned all who claimed the Jewish Messiah had already come, and Christianity in particular. The formulated prayer in question (birkat ha-minim) is considered by other scholars to be, however, unremarkable in the history of Jewish and Christian relations.

There is a paucity of evidence for Jewish persecution of "heretics" in general, or Christians in particular, in the period between 70 and 135. It is probable that the condemnation of Jamnia included many groups, of which the Christians were but one, and did not necessarily mean excommunication. That some of the later church fathers only recommended against synagogue attendance makes it improbable that an anti-Christian prayer was a common part of the synagogue liturgy. Jewish Christians continued to worship in synagogues for centuries.[38][39][40]

Other actions, however, such as the rejection of the Septuagint translation, are attributed to the "School of Jamnia". Early church teachers and writers reacted with even stronger devotion, citing the Septuagint's antiquity and its use by the Evangelists and Apostles. Being the Old Testament quoted by the Canonical Gospels (according to Greek primacy) and the Greek Church Fathers, the Septuagint had an essentially official status in the early Christian world,[41] and is still considered to be the Old Testament text in the Greek Orthodox church, see also Development of the Old Testament canon.

Status under Roman law

During the late 1st century, Rome considered Judaism a legitimate religion, with protections and exemptions under Roman law that had been negotiated over two centuries (see also Anti-Judaism in the pre-Christian Roman Empire). Observant Jews had special rights, including the privilege of abstaining from the civic rites of ancient Roman religion. Failure to support public religion could otherwise be viewed as treasonous, since the Romans regarded their traditional religion as necessary for preserving the stability and prosperity of the state (see Religio and the state).

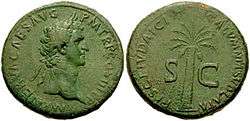

Christianity at first had been regarded by the Romans as a sect of Judaism, but eventually as a distinct religion requiring separate legal provisions. The distinction between Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism was recognized by the emperor Nerva around 98 CE in a decree granting Christians an exemption from paying the Fiscus judaicus, the annual tax upon the Jews. From that time, Roman literary sources begin to distinguish between Christians and Jews.

In his letters to Trajan, Pliny assumes that Christians are not Jews because they do not pay the tax. Since paying taxes had been one of the ways that Jews demonstrated their goodwill and loyalty toward the Empire, Christians were left to negotiate their own alternatives to participating in Imperial cult; their inability or refusal to do so resulted at times in martyrdom and persecution.[44][45][46] The Church Father Tertullian, for instance, had attempted to argue that Christianity was not inherently treasonous, and that Christians could offer their own form of prayer for the wellbeing of the emperor.[47] Christianity was formally recognized as a legitimate religion by the Edict of Milan in 313.

Marcion of Sinope

Marcion of Sinope, a bishop of Asia Minor who went to Rome and was later excommunicated for his views, was the first of record to propose a definitive, exclusive, unique canon of Christian scriptures, compiled sometime between 130 and 140 AD. In his book Origin of the New Testament[48] Adolf von Harnack argued that Marcion viewed the church at this time as largely an Old Testament church (one that "follows the Testament of the Creator-God") without a firmly established New Testament canon, and that the church gradually formulated its New Testament canon in response to the challenge posed by Marcion.

Marcion endorsed a form of Christianity that excluded Jewish doctrines and the Hebrew Bible, with Paul as the only reliable source of authentic doctrine. Paul was, according to Marcion, the only apostle who had rightly understood the new message of salvation as delivered by Christ.[49]

Marcion's canon and theology were rejected as heretical by Tertullian and Epiphanius and the growing movement of Proto-orthodox Christianity; however, he forced other Christians to consider which texts were canonical and why, see Development of the New Testament canon.

Timeline of events

Various events in the 1st and 2nd centuries contributed to or marked the widening split between Christianity and Judaism. The following listing of these events is in rough historical order, as dates for some are disputed.

1st century

New Testament

- Actions of Jesus "cleansing the temple" and trial by Sanhedrin according to the Gospels (c. 30), both of which are accepted by the majority of modern scholars as significant actions by the Historical Jesus, but rejected by more radical critics; see also Rejection of Jesus and the Jesus Seminar's Acts of Jesus.[50]

- Peter's speech at the Jerusalem Temple accusing the Israelites of killing Jesus according to Acts 3:12–4:4,[51] c 34, see also Responsibility for the death of Jesus and Josephus on Jesus.

- Stephen before a Sanhedrin, his speech and stoning according to Acts 6:8–8:1,[52] c 35.

- Baptism of Cornelius the Centurion by Peter according to Acts 10,[53] traditionally considered the first gentile convert to Christianity[54]

- martyrdom of James, son of Zebedee by Agrippa I according to Acts 12:1–2,[55] c 44

- Paul's proselytization of gentiles as "Apostle to the Gentiles" (see also Proselytes and Godfearers and Paul of Tarsus and Judaism), 1st mission c 45

- Incident at Antioch[56] where Paul accused Peter of Judaizing, but even Barnabas sided with Peter, c 49

- Council of Jerusalem, c 50, which allowed gentile converts who did not also "convert to Judaism", or another interpretation: decreed proto-Noahide Law,[57] see also Circumcision controversy in early Christianity and Dual-covenant theology.

- Paul, persecuted by the Jews of Jerusalem, on charges of Antinomianism, is saved by the Romans and sent to Rome.[58]

- Woes of the Pharisees, Lament over Jerusalem,[59] Great Commission[60] from the Gospel of Matthew and Gospel of Luke, c 80, earlier if actually spoken by Jesus.

- Epistle to the Hebrews and the New Covenant, which some date as pre-AD 70, given that the argument of the letter presupposes that temple worship and sacrifice were in operation at the time of the writing. If post AD 70, the writer would have used the destruction of the temple and the discontinuation of sacrifices as proof of the passing of the Old Covenant and the institution and superiority of the New, unless he was trying to make the document appear older. The term "New Covenant" also appears in the Pauline epistles, some copies of the Gospel of Luke, and the Septuagint.

- John 6:60–6:66[61] records "many disciples" (who at the time were largely Jewish) leaving Jesus after he said that those who eat his body and drink his blood will remain in him and have eternal life,[62] for interpretations of this passage, see Transubstantiation, c 90–100,[63] earlier if actually spoken by Jesus

Other Sources

- Census of Quirinius and creation of Iudaea Province, c. 6

- John the Baptist is executed by Herod Antipas, c 30, recorded in Jewish Antiquities 18.5.2

- Crisis under Caligula, 37–41, proposed as the first open break between Rome and the Jews[64]

- Claudius's expulsion of Jews from Rome,[65] 49

- James the Just, considered the 1st Christian bishop of Jerusalem, is stoned at the instigation of the High Priest, c. 62, according to Jewish Antiquities 20.9.1.

- Development of Christian scripture, starting with Paul's Epistle to the Galatians which many scholars date either just before or after the Jerusalem Council.

- Destruction of the Second Temple and institution of the Fiscus Iudaicus, the Roman annual head tax on all Jews to pay for upkeep of the Jupiter Capitolinus temple in Rome instead of the Jerusalem Temple, Vespasian orders arrest of all descendants of King David according to Eusebius' Church History 3.12, 70

- Hypothetical Council of Jamnia may have excluded the Christian scriptures and may have excluded Jewish Christians as Minuth, c 90

- Domitian applied the Fiscus Iudaicus tax even to those who merely "lived like Jews",[66] c 90

- Titus Flavius Clemens (consul) condemned to death by the Roman Senate for conversion to Judaism, 95

- Nerva relaxed the Fiscus Iudaicus applying it only to those who professed to be practicing Judaism, c. 96

2nd century

- The 3rd bishop of Antioch, Ignatius's Letter to the Magnesians 9–10 against Sabbath in Christianity and Judaizers , c 100

- crucifixion of the 2nd bishop of Jerusalem, Simeon of Jerusalem, c 107[67]

- Certain Gospels (not necessarily limited to those in the modern canon, see also Jewish-Christian Gospels) begin to be discussed by Jewish writers, who refer to them as Gilyonim. Rabbi Tarfon possibly advocated burning them, c 120, but this is a disputed reading.[68][69]

- controversial claim of Simon bar Kokhba to be the Jewish Messiah, 132–135, rejected by Rabbinic Judaism, final result of the revolt was the expulsion of Jews from Jerusalem which was rebuilt as Aelia Capitolina, end of Christian "bishops of the circumcision" according to Eusebius' Church History 4.5, Caesarea Maritima became the center of Palestinian Christianity (the Metropolitan bishops over the Jerusalem Suffragan bishops) while the Great Sanhedrin of Judaism had previously relocated to Yavne.

- controversial claim of Marcion against the Jewish Bible, c 144, rejected by Proto-orthodox Christianity

- Epistle to Diognetus polemic against the Jews, c 150

- Martyrdom of Polycarp implicates the Jews, c 150

- Justin Martyr's Dialogue with Trypho, a Jew , c 150

- Octavius of Marcus Minucius Felix, for example : "XXXVIII.—To the Jews. Evil always, and recalcitrant ...", c 180

- excommunication of Quartodecimanism by Pope Victor I whose decree was unpopular in the East and perhaps rescinded,[70] c 190

- Tertullian's Adversus Judaeos/An Answer to the Jews , c 200

See also

References

- ↑ Robert Goldenberg. Review of Dying for God: Martyrdom and the Making of Christianity and Judaism by Daniel Boyarin in The Jewish Quarterly Review, New Series, Vol. 92, No. 3/4 (Jan.–Apr., 2002), pp. 586–588

- ↑ Daniel Boyarin, Dying for God: Martyrdom and the Making of Christianity and Judaism

- ↑ Daniel Boyarin. Dying for God: Martyrdom and the Making of Christianity and Judaism. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999, p. 15.

- ↑ Jews and Christians: The Parting of the Ways by Durham-Tubingen Research Symposium on Earliest Christianity and Judaism (2nd: 1989: University of Durham), James D. G. Dunn

- ↑ Robert M. Price "Christianity, Diaspora Judaism, and Roman Crisis"

- ↑ "How many Jews became Christians in the first century? The failure of the Christian mission to the Jews" (PDF). Australian Catholic University. Australia. 2005. Retrieved 2014-01-14.

- ↑ Daniel Boyarin (2012). The Jewish Gospels: The Story of the Jewish Christ. New Press. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ↑ Israel Knohl (2000). The Messiah Before Jesus: The Suffering Servant of the Dead Sea Scrolls. University of California Press. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ↑ Alan J. Avery-Peck, ed. (2005). The Review of Rabbinic Judaism: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 91–112. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer (2012). The Jewish Jesus: How Judaism and Christianity Shaped Each Other. Princeton University Press. pp. 235–238. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ↑ Alan F. Segal, Rebecca's Children: Judaism and Christianity in the Roman World, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1986.

- ↑ Martin Buber, "The Two Foci of the Jewish Soul," cited in The Writings of Martin Buber, Will Herberg (editor), New York: Meridian Books, 1956, p. 276.

- ↑ H.H. Ben-Sasson, A History of the Jewish People, Harvard University Press, 1976, ISBN 0-674-39731-2, The Crisis Under Gaius Caligula, pages 254–256: "The reign of Gaius Caligula (37–41) witnessed the first open break between the Jews and the Julio-Claudian empire. Until then—if one accepts Sejanus' heyday and the trouble caused by the census after Archelaus's banishment—there was usually an atmosphere of understanding between the Jews and the empire … These relations deteriorated seriously during Caligula's reign, and, though after his death the peace was outwardly re-established, considerable bitterness remained on both sides. … Caligula ordered that a golden statue of himself be set up in the Temple in Jerusalem. … Only Caligula's death, at the hands of Roman conspirators (41), prevented the outbreak of a Jewish-Roman war that might well have spread to the entire East."

- 1 2 Shaye J.D. Cohen 1987 From the Maccabees to the Mishnah Library of Early Christianity, Wayne Meeks, editor. The Westminster Press. 167–168

- 1 2 Paula Fredricksen, From Jesus to Christ Yale university Press. pp. 133–134

- 1 2 Paula Fredricksen, From Jesus to Christ Yale university Press. pp. 136-142

- ↑ McGrath, Alister E., Christianity: An Introduction. Blackwell Publishing (2006). ISBN 1-4051-0899-1. Page 174: "In effect, they Jewish Christians seemed to regard Christianity as an affirmation of every aspect of contemporary Judaism, with the addition of one extra belief—that Jesus was the Messiah. Unless males were circumcised, they could not be saved (Acts 15:1)."

- ↑ Jewish Encyclopedia: Baptism: "According to rabbinical teachings, which dominated even during the existence of the Temple (Pes. viii. 8), Baptism, next to circumcision and sacrifice, was an absolutely necessary condition to be fulfilled by a proselyte to Judaism (Yeb. 46b, 47b; Ker. 9a; 'Ab. Zarah 57a; Shab. 135a; Yer. Kid. iii. 14, 64d). Circumcision, however, was much more important, and, like baptism, was called a "seal" (Schlatter, "Die Kirche Jerusalems," 1898, p. 70).

- 1 2 Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church ed. F.L. Lucas (Oxford) entry on St. Paul

- ↑ Boyarin, Daniel (1997). A Radical Jew. Berkeley [u.a.]

- ↑ Boyarin, Daniel (1997). A radical Jew : Paul and the politics of identity (1. paperback printing. ed.). Berkeley [u.a.]: Univ. of California Press. ISBN 978-0520212145.

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia: Gamaliel

- 1 2 3 Shaye J.D. Cohen 1987 From the Maccabees to the Mishnah Library of Early Christianity, Wayne Meeks, editor. The Westminster Press. 168

- ↑ Ignatius' Epistle to the Magnesians chapter 9 at ccel.org

- ↑ According to Eusebius' Life of Constantine, Constantine's speech at the council included: "Let us then have nothing in common with the detestable Jewish crowd; for we have received from our Saviour a different way." Eusebius, Life of Constantine Vol. III Ch. XVIII Life of Constantine (Book III), Chapter 18: He speaks of their Unanimity respecting the Feast of Easter, and against the Practice of the Jews.

- ↑ McManners, Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity (2002), p. 37, Chapter 1 The Early Christian Community subsection entitled "Rome" by Henry Chadwick, quote: "In Acts 15 scripture recorded the apostles meeting in synod to reach a common policy about the Gentile mission."

- ↑ The Rabbis, probably after Bar Kokhba's revolt, instituted the "peri'ah" (the laying bare of the glans), without which circumcision was declared to be of no value (Shab. xxx. 6).

- ↑ Karl Josef von Hefele's commentary on canon II of Gangra notes: "We further see that, at the time of the Synod of Gangra, the rule of the Apostolic Synod with regard to blood and things strangled was still in force. With the Greeks, indeed, it continued always in force as their Euchologies still show. Balsamon also, the well-known commentator on the canons of the Middle Ages, in his commentary on the sixty-third Apostolic Canon, expressly blames the Latins because they had ceased to observe this command. What the Latin Church, however, thought on this subject about the year 400, is shown by St. Augustine in his work Contra Faustum, where he states that the Apostles had given this command in order to unite the heathens and Jews in the one ark of Noah; but that then, when the barrier between Jewish and heathen converts had fallen, this command concerning things strangled and blood had lost its meaning, and was only observed by few. But still, as late as the eighth century, Pope Gregory the Third (731) forbade the eating of blood or things strangled under threat of a penance of forty days. No one will pretend that the disciplinary enactments of any council, even though it be one of the undisputed Ecumenical Synods, can be of greater and more unchanging force than the decree of that first council, held by the Holy Apostles at Jerusalem, and the fact that its decree has been obsolete for centuries in the West is proof that even Ecumenical canons may be of only temporary utility and may be repealed by disuse, like other laws."

- ↑ Cohen, Shaye J.D. (1988). From the Maccabees to the Mishnah ISBN 0-664-25017-3 p. 228

- ↑ Cohen, Shaye J.D. (1988). From the Maccabees to the Mishnah ISBN 0-664-25017-3 pp. 224–225

- ↑ Eusebius, Church History 3, 5, 3; Epiphanius, Panarion 29,7,7-8; 30, 2, 7; On Weights and Measures 15. On the flight to Pella see: Bourgel, Jonathan, "The Jewish Christians’ Move from Jerusalem as a pragmatic choice", in: Dan Jaffe (ed), Studies in Rabbinic Judaism and Early Christianity, (Leyden: Brill, 2010), p. 107-138; P. H. R. van Houwelingen, "Fleeing forward: The departure of Christians from Jerusalem to Pella," Westminster Theological Journal 65 (2003), 181-200.

- ↑ Jacob Neusner 1984 Toah From our Sages Rossell Books. p. 175

- ↑ See, Strack, Hermann, Introduction to the Talmud and Midrash, Jewish Publication Society, 1945. pp.11–12. "[The Oral Law] was handed down by word of mouth during a long period. … The first attempts to write down the traditional matter, there is reason to believe, date from the first half of the second post-Christian century." Strack theorizes that the growth of a Christian canon (the New Testament) was a factor that influenced the Rabbis to record the oral law in writing.

- ↑ See, for example, Grayzel, A History of the Jews, Penguin Books, 1984, p. 193.

- ↑ Shaye J.D. Cohen 1987 From the Maccabees to the Mishnah Library of Early Christianity, Wayne Meeks, editor. The Westminster Press. 224–228

- ↑ Paula Fredriksen, 1988 From Jesus to Christ, Yale University Press. 167-170

- ↑ Raymond Apple, "Jewish attitudes to Gentiles in the First Century"

- ↑ Wylen (1995). Pg 190.

- ↑ Berard (2006). Pp 112–113.

- ↑ Wright (1992). Pp 164–165.

- ↑ "The Septuagint" The Ecole Glossary. 27 Dec 2009

- ↑ As translated by Molly Whittaker, Jews and Christians: Graeco-Roman Views, (Cambridge University Press, 1984), p. 105.

- ↑ Martin Goodman, "Nerva, the Fiscus Judaicus and Jewish Identity," Journal of Roman Studies 79 (1989) 40–44.

- ↑ Wylen (1995). Pp 190–192.

- ↑ Dunn (1999). Pp 33–34.

- ↑ Boatwright (2004). Pg 426.

- ↑ Tertullian, Apologeticus 30.1, as discussed by Cecilia Ames, "Roman Religion in the Vision of Tertullian," in A Companion to Roman Religion (Blackwell, 2007), pp. 467–468 et passim.

- ↑ von Harnack, Adolf (1914). Origin of the New Testament.

- ↑ The 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article on Marcion

- ↑ The Temple Incident (Mark 11:15–19 and parallels) is a pink event, Before the Council is a "core event not accurately recorded"

- ↑ Acts 3:12–4:4

- ↑ Acts 6:8–8:1

- ↑ Acts 10

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia: Cornelius: "The baptism of Cornelius is an important event in the history of the Early Church. The gates of the Church, within which thus far only those who were circumcised and observed the Law of Moses had been admitted, were now thrown open to the uncircumcised Gentiles without the obligation of submitting to the Jewish ceremonial laws. The innovation was disapproved by the Jewish Christians at Jerusalem (Acts 11:2–3); but when Peter had related his own and Cornelius's vision and how the Holy Ghost had come down upon the new converts, opposition ceased (Acts 11:4–18) except on the part of a few extremists. The matter was finally settled at the Council of Jerusalem (Acts 15)."

- ↑ Acts 12:1–2

- ↑ Gal 2:11–21, Catholic Encyclopedia: Judaizers see section titled: "The Incident At Antioch"

- ↑ Augustine's Contra Faustum 32.13: "The observance of pouring out the blood which was enjoined in ancient times upon Noah himself after the deluge, the meaning of which we have already explained, is thought by many to be what is meant in the Acts of the Apostles, where we read that the Gentiles were required to abstain from fornication, and from things sacrificed, and from blood, that is, from flesh of which the blood has not been poured out."

- ↑ Acts 21:1–28:31

- ↑ Matt 23:37–39, Luke 13:31–35

- ↑ The Great Commission advocates Jesus' teachings for all nations whereas Rabbinic Judaism advocates full Jewish Law only for Jews and converts with the Seven Laws of Noah for other nations.

- ↑ John 6:60–6:66

- ↑ 6:48–59

- ↑ Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.

- ↑ H.H. Ben-Sasson, A History of the Jewish People, Harvard University Press, 1976, ISBN 0-674-39731-2, The Crisis Under Gaius Caligula, pages 254–256: "The reign of Gaius Caligula (37–41) witnessed the first open break between the Jews and the Julio-Claudian empire. Until then—if one accepts Sejanus' heyday and the trouble caused by the census after Archelaus' banishment—there was usually an atmosphere of understanding between the Jews and the empire … These relations deteriorated seriously during Caligula's reign, and, though after his death the peace was outwardly re-established, considerable bitterness remained on both sides. … Caligula ordered that a golden statue of himself be set up in the Temple in Jerusalem. … Only Caligula's death, at the hands of Roman conspirators (41), prevented the outbreak of a Jewish-Roman war that might well have spread to the entire East."

- ↑ Lives of the Twelve Caesars, Claudius XXV.4, referenced in Acts 18:2

- ↑ See Jewish Encyclopedia: Fiscus Iudaicus The following is a direct quote (including editor's notes in brackets) of a translation of Suetonius's Domitian XII: "Besides other taxes, that on the Jews [A tax of two drachmas a head, imposed by Titus in return for free permission to practice their religion; see Josephus, Bell. Jud. 7.6.6] was levied with the utmost rigor, and those were prosecuted who, without publicly acknowledging that faith, yet lived as Jews, as well as those who concealed their origin and did not pay the tribute levied upon their people [These may have been Christians, whom the Romans commonly assumed were Jews]. I recall being present in my youth when the person of a man ninety years old was examined before the procurator and a very crowded court, to see whether he was circumcised."

- ↑ possibly with Jewish involvement: Eusebius' Church History 3.32.4: "And the same writer says that his accusers also, when search was made for the descendants of David, were arrested as belonging to that family." Sidenote 879: "This is a peculiar statement. Members of the house of David would hardly have ventured to accuse Symeon on the ground that he belonged to that house. The statement is, however, quite indefinite. We are not told what happened to these accusers, nor indeed that they really were of David's line, although the ὡσ€ν with which Eusebius introduces the charge does not imply any doubt in his own mind, as Lightfoot quite rightly remarks. It is possible that some who were of the line of David may have accused Symeon, not of being a member of that family, but only of being a Christian, and that the report of the occurrence may have become afterward confused."

- ↑ Kuhn (1960) and Maier (1962) cited by Paget in 'The Written Gospel' (2005), pg 210

- ↑ Friedlander (1899) cited in Pearson in 'Gnosticism, Judaism and Egyptian Christianity' (1990)

- ↑ Eusebius. "Church History". p. 5.24.: "Victor, head of the Roman church, attempted at one stroke to cut off from the common unity all the Asian [Eastern] dioceses. ... But this was not to the taste of all the bishops: They replied with a request that he would turn his mind to the things that make for peace and for unity and love towards his neighbors. We still possess the words of these men, who very sternly rebuked Victor."