Stack (abstract data type)

In computer science, a stack is an abstract data type that serves as a collection of elements, with two principal operations: push, which adds an element to the collection, and pop, which removes the most recently added element that was not yet removed. The order in which elements come off a stack gives rise to its alternative name, LIFO (for last in, first out). Additionally, a peek operation may give access to the top without modifying the stack.

The name "stack" for this type of structure comes from the analogy to a set of physical items stacked on top of each other, which makes it easy to take an item off the top of the stack, while getting to an item deeper in the stack may require taking off multiple other items first.[1]

Considered as a linear data structure, or more abstractly a sequential collection, the push and pop operations occur only at one end of the structure, referred to as the top of the stack. This makes it possible to implement a stack as a singly linked list and a pointer to the top element.

A stack may be implemented to have a bounded capacity. If the stack is full and does not contain enough space to accept an entity to be pushed, the stack is then considered to be in an overflow state. The pop operation removes an item from the top of the stack.

History

Stacks entered the computer science literature in 1946, in the computer design of Alan M. Turing (who used the terms "bury" and "unbury") as a means of calling and returning from subroutines.[2] Subroutines had already been implemented in Konrad Zuse's Z4 in 1945. Klaus Samelson and Friedrich L. Bauer of Technical University Munich proposed the idea in 1955 and filed a patent in 1957.[3] The same concept was developed, independently, by the Australian Charles Leonard Hamblin in the first half of 1957.[4]

Stacks are often described by analogy to a spring-loaded stack of plates in a cafeteria.[5][1][6] Clean plates are placed on top of the stack, pushing down any already there. When a plate is removed from the stack, the one below it pops up to become the new top.

Non-essential operations

In many implementations, a stack has more operations than "push" and "pop". An example is "top of stack", or "peek", which observes the top-most element without removing it from the stack.[7] Since this can be done with a "pop" and a "push" with the same data, it is not essential. An underflow condition can occur in the "stack top" operation if the stack is empty, the same as "pop". Also, implementations often have a function which just returns whether the stack is empty.

Software stacks

Implementation

A stack can be easily implemented either through an array or a linked list. What identifies the data structure as a stack in either case is not the implementation but the interface: the user is only allowed to pop or push items onto the array or linked list, with few other helper operations. The following will demonstrate both implementations, using pseudocode.

Array

An array can be used to implement a (bounded) stack, as follows. The first element (usually at the zero offset) is the bottom, resulting in array[0] being the first element pushed onto the stack and the last element popped off. The program must keep track of the size (length) of the stack, using a variable top that records the number of items pushed so far, therefore pointing to the place in the array where the next element is to be inserted (assuming a zero-based index convention). Thus, the stack itself can be effectively implemented as a three-element structure:

structure stack:

maxsize : integer

top : integer

items : array of item

procedure initialize(stk : stack, size : integer): stk.items ← new array of size items, initially empty stk.maxsize ← size stk.top ← 0

The push operation adds an element and increments the top index, after checking for overflow:

procedure push(stk : stack, x : item): if stk.top = stk.maxsize: report overflow error else: stk.items[stk.top] ← x stk.top ← stk.top + 1

Similarly, pop decrements the top index after checking for underflow, and returns the item that was previously the top one:

procedure pop(stk : stack):

if stk.top = 0:

report underflow error

else:

stk.top ← stk.top − 1

r ← stk.items[stk.top]

Using a dynamic array, it is possible to implement a stack that can grow or shrink as much as needed. The size of the stack is simply the size of the dynamic array, which is a very efficient implementation of a stack since adding items to or removing items from the end of a dynamic array requires amortized O(1) time.

Linked list

Another option for implementing stacks is to use a singly linked list. A stack is then a pointer to the "head" of the list, with perhaps a counter to keep track of the size of the list:

structure frame:

data : item

next : frame or nil

structure stack:

head : frame or nil

size : integer

procedure initialize(stk : stack):

stk.head ← nil

stk.size ← 0

Pushing and popping items happens at the head of the list; overflow is not possible in this implementation (unless memory is exhausted):

procedure push(stk : stack, x : item): newhead ← new frame newhead.data ← x newhead.next ← stk.head stk.head ← newhead stk.size ← stk.size + 1

procedure pop(stk : stack):

if stk.head = nil:

report underflow error

r ← stk.head.data

stk.head ← stk.head.next

stk.size ← stk.size - 1

return r

Stacks and programming languages

Some languages, such as Perl, LISP and Python, make the stack operations push and pop available on their standard list/array types. Some languages, notably those in the Forth family (including PostScript), are designed around language-defined stacks that are directly visible to and manipulated by the programmer.

The following is an example of manipulating a stack in Common Lisp (">" is the Lisp interpreter's prompt; lines not starting with ">" are the interpreter's responses to expressions):

> (setf stack (list 'a 'b 'c)) ;; set the variable "stack"

(A B C)

> (pop stack) ;; get top (leftmost) element, should modify the stack

A

> stack ;; check the value of stack

(B C)

> (push 'new stack) ;; push a new top onto the stack

(NEW B C)

Several of the C++ Standard Library container types have push_back and pop_back operations with LIFO semantics; additionally, the stack template class adapts existing containers to provide a restricted API with only push/pop operations. PHP has an SplStack class. Java's library contains a Stack class that is a specialization of Vector. Following is an example program in Java language, using that class.

import java.util.*;

class StackDemo {

public static void main(String[]args) {

Stack<String> stack = new Stack<String>();

stack.push("A"); // Insert "A" in the stack

stack.push("B"); // Insert "B" in the stack

stack.push("C"); // Insert "C" in the stack

stack.push("D"); // Insert "D" in the stack

System.out.println(stack.peek()); // Prints the top of the stack ("D")

stack.pop(); // removing the top ("D")

stack.pop(); // removing the next top ("C")

}

}

Hardware stacks

A common use of stacks at the architecture level is as a means of allocating and accessing memory.

Basic architecture of a stack

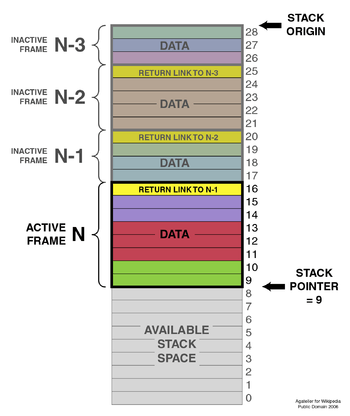

A typical stack is an area of computer memory with a fixed origin and a variable size. Initially the size of the stack is zero. A stack pointer, usually in the form of a hardware register, points to the most recently referenced location on the stack; when the stack has a size of zero, the stack pointer points to the origin of the stack.

The two operations applicable to all stacks are:

- a push operation, in which a data item is placed at the location pointed to by the stack pointer, and the address in the stack pointer is adjusted by the size of the data item;

- a pop or pull operation: a data item at the current location pointed to by the stack pointer is removed, and the stack pointer is adjusted by the size of the data item.

There are many variations on the basic principle of stack operations. Every stack has a fixed location in memory at which it begins. As data items are added to the stack, the stack pointer is displaced to indicate the current extent of the stack, which expands away from the origin.

Stack pointers may point to the origin of a stack or to a limited range of addresses either above or below the origin (depending on the direction in which the stack grows); however, the stack pointer cannot cross the origin of the stack. In other words, if the origin of the stack is at address 1000 and the stack grows downwards (towards addresses 999, 998, and so on), the stack pointer must never be incremented beyond 1000 (to 1001, 1002, etc.). If a pop operation on the stack causes the stack pointer to move past the origin of the stack, a stack underflow occurs. If a push operation causes the stack pointer to increment or decrement beyond the maximum extent of the stack, a stack overflow occurs.

Some environments that rely heavily on stacks may provide additional operations, for example:

- Duplicate: the top item is popped, and then pushed again (twice), so that an additional copy of the former top item is now on top, with the original below it.

- Peek: the topmost item is inspected (or returned), but the stack pointer is not changed, and the stack size does not change (meaning that the item remains on the stack). This is also called top operation in many articles.

- Swap or exchange: the two topmost items on the stack exchange places.

- Rotate (or Roll): the n topmost items are moved on the stack in a rotating fashion. For example, if n=3, items 1, 2, and 3 on the stack are moved to positions 2, 3, and 1 on the stack, respectively. Many variants of this operation are possible, with the most common being called left rotate and right rotate.

Stacks are often visualized growing from the bottom up (like real-world stacks). They may also be visualized growing from left to right, so that "topmost" becomes "rightmost", or even growing from top to bottom. The important feature is that the bottom of the stack is in a fixed position. The illustration in this section is an example of a top-to-bottom growth visualization: the top (28) is the stack "bottom", since the stack "top" is where items are pushed or popped from.

A right rotate will move the first element to the third position, the second to the first and the third to the second. Here are two equivalent visualizations of this process:

apple banana banana ===right rotate==> cucumber cucumber apple

cucumber apple banana ===left rotate==> cucumber apple banana

A stack is usually represented in computers by a block of memory cells, with the "bottom" at a fixed location, and the stack pointer holding the address of the current "top" cell in the stack. The top and bottom terminology are used irrespective of whether the stack actually grows towards lower memory addresses or towards higher memory addresses.

Pushing an item on to the stack adjusts the stack pointer by the size of the item (either decrementing or incrementing, depending on the direction in which the stack grows in memory), pointing it to the next cell, and copies the new top item to the stack area. Depending again on the exact implementation, at the end of a push operation, the stack pointer may point to the next unused location in the stack, or it may point to the topmost item in the stack. If the stack points to the current topmost item, the stack pointer will be updated before a new item is pushed onto the stack; if it points to the next available location in the stack, it will be updated after the new item is pushed onto the stack.

Popping the stack is simply the inverse of pushing. The topmost item in the stack is removed and the stack pointer is updated, in the opposite order of that used in the push operation.

Hardware support

Stack in main memory

Many CPU families, including the x86, Z80 and 6502, have a dedicated register reserved for use as (call) stack pointers and special push and pop instructions that manipulate this specific register, conserving opcode space. Some processors, like the PDP-11 and the 68000, also have special addressing modes for implementation of stacks, typically with a semi-dedicated stack pointer as well (such as A7 in the 68000). However, in most processors, several different registers may be used as additional stack pointers as needed (whether updated via addressing modes or via add/sub instructions).

Stack in registers or dedicated memory

The x87 floating point architecture is an example of a set of registers organised as a stack where direct access to individual registers (relative the current top) is also possible. As with stack-based machines in general, having the top-of-stack as an implicit argument allows for a small machine code footprint with a good usage of bus bandwidth and code caches, but it also prevents some types of optimizations possible on processors permitting random access to the register file for all (two or three) operands. A stack structure also makes superscalar implementations with register renaming (for speculative execution) somewhat more complex to implement, although it is still feasible, as exemplified by modern x87 implementations.

Sun SPARC, AMD Am29000, and Intel i960 are all examples of architectures using register windows within a register-stack as another strategy to avoid the use of slow main memory for function arguments and return values.

There are also a number of small microprocessors that implements a stack directly in hardware and some microcontrollers have a fixed-depth stack that is not directly accessible. Examples are the PIC microcontrollers, the Computer Cowboys MuP21, the Harris RTX line, and the Novix NC4016. Many stack-based microprocessors were used to implement the programming language Forth at the microcode level. Stacks were also used as a basis of a number of mainframes and mini computers. Such machines were called stack machines, the most famous being the Burroughs B5000.

Applications

Expression evaluation and syntax parsing

Calculators employing reverse Polish notation use a stack structure to hold values. Expressions can be represented in prefix, postfix or infix notations and conversion from one form to another may be accomplished using a stack. Many compilers use a stack for parsing the syntax of expressions, program blocks etc. before translating into low level code. Most programming languages are context-free languages, allowing them to be parsed with stack based machines.

Backtracking

Another important application of stacks is backtracking. Consider a simple example of finding the correct path in a maze. There are a series of points, from the starting point to the destination. We start from one point. To reach the final destination, there are several paths. Suppose we choose a random path. After following a certain path, we realise that the path we have chosen is wrong. So we need to find a way by which we can return to the beginning of that path. This can be done with the use of stacks. With the help of stacks, we remember the point where we have reached. This is done by pushing that point into the stack. In case we end up on the wrong path, we can pop the last point from the stack and thus return to the last point and continue our quest to find the right path. This is called backtracking.

The prototypical example of a backtracking algorithm is depth-first search, which finds all vertices of a graph that can be reached from a specified starting vertex. Other applications of backtracking involve searching through spaces that represent potential solutions to an optimization problem. Branch and bound is a technique for performing such backtracking searches without exhaustively searching all of the potential solutions in such a space.

Runtime memory management

A number of programming languages are stack-oriented, meaning they define most basic operations (adding two numbers, printing a character) as taking their arguments from the stack, and placing any return values back on the stack. For example, PostScript has a return stack and an operand stack, and also has a graphics state stack and a dictionary stack. Many virtual machines are also stack-oriented, including the p-code machine and the Java Virtual Machine.

Almost all calling conventions—

Some programming languages use the stack to store data that is local to a procedure. Space for local data items is allocated from the stack when the procedure is entered, and is deallocated when the procedure exits. The C programming language is typically implemented in this way. Using the same stack for both data and procedure calls has important security implications (see below) of which a programmer must be aware in order to avoid introducing serious security bugs into a program.

Efficient algorithms

Several algorithms use a stack (separate from the usual function call stack of most programming languages) as the principle data structure with which they organize their information. These include:

- Graham scan, an algorithm for the convex hull of a two-dimensional system of points. A convex hull of a subset of the input is maintained in a stack, which is used to find and remove concavities in the boundary when a new point is added to the hull.[8]

- Part of the SMAWK algorithm for finding the row minima of a monotone matrix uses stacks in a similar way to Graham scan.[9]

- All nearest smaller values, the problem of finding, for each number in an array, the closest preceding number that is smaller than it. One algorithm for this problem uses a stack to maintain a collection of candidates for the nearest smaller value. For each position in the array, the stack is popped until a smaller value is found on its top, and then the value in the new position is pushed onto the stack.[10]

- The nearest-neighbor chain algorithm, a method for agglomerative hierarchical clustering based on maintaining a stack of clusters, each of which is the nearest neighbor of its predecessor on the stack. When this method finds a pair of clusters that are mutual nearest neighbors, they are popped and merged.[11]

Security

Some computing environments use stacks in ways that may make them vulnerable to security breaches and attacks. Programmers working in such environments must take special care to avoid the pitfalls of these implementations.

For example, some programming languages use a common stack to store both data local to a called procedure and the linking information that allows the procedure to return to its caller. This means that the program moves data into and out of the same stack that contains critical return addresses for the procedure calls. If data is moved to the wrong location on the stack, or an oversized data item is moved to a stack location that is not large enough to contain it, return information for procedure calls may be corrupted, causing the program to fail.

Malicious parties may attempt a stack smashing attack that takes advantage of this type of implementation by providing oversized data input to a program that does not check the length of input. Such a program may copy the data in its entirety to a location on the stack, and in so doing it may change the return addresses for procedures that have called it. An attacker can experiment to find a specific type of data that can be provided to such a program such that the return address of the current procedure is reset to point to an area within the stack itself (and within the data provided by the attacker), which in turn contains instructions that carry out unauthorized operations.

This type of attack is a variation on the buffer overflow attack and is an extremely frequent source of security breaches in software, mainly because some of the most popular compilers use a shared stack for both data and procedure calls, and do not verify the length of data items. Frequently programmers do not write code to verify the size of data items, either, and when an oversized or undersized data item is copied to the stack, a security breach may occur.

See also

References

- 1 2 Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L.; Stein, Clifford (2009) [1990]. Introduction to Algorithms (3rd ed.). MIT Press and McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-262-03384-4.

- ↑ Newton, David E. (2003). Alan Turing: a study in light and shadow. Philadelphia: Xlibris. p. 82. ISBN 9781401090791. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ↑ Dr. Friedrich Ludwig Bauer and Dr. Klaus Samelson (30 March 1957). "Verfahren zur automatischen Verarbeitung von kodierten Daten und Rechenmaschine zur Ausübung des Verfahrens" (in German). Germany, Munich: Deutsches Patentamt. Retrieved 2010-10-01.

- ↑ C. L. Hamblin, "An Addressless Coding Scheme based on Mathematical Notation", N.S.W University of Technology, May 1957 (typescript)

- ↑ Ball, John A. (1978). Algorithms for RPN calculators (1 ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Wiley-Interscience, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 0-471-03070-8.

- ↑ Godse, A. P.; Godse, D. A. (2010-01-01). Computer Architecture. Technical Publications. pp. 1–56. ISBN 9788184315349. Retrieved 2015-01-30.

- ↑ Horowitz, Ellis: "Fundamentals of Data Structures in Pascal", page 67. Computer Science Press, 1984

- ↑ Graham, R.L. (1972). An Efficient Algorithm for Determining the Convex Hull of a Finite Planar Set. Information Processing Letters 1, 132-133

- ↑ Aggarwal, Alok; Klawe, Maria M.; Moran, Shlomo; Shor, Peter; Wilber, Robert (1987), "Geometric applications of a matrix-searching algorithm", Algorithmica, 2 (2): 195–208, doi:10.1007/BF01840359, MR 895444.

- ↑ Berkman, Omer; Schieber, Baruch; Vishkin, Uzi (1993), "Optimal doubly logarithmic parallel algorithms based on finding all nearest smaller values", Journal of Algorithms, 14 (3): 344–370, doi:10.1006/jagm.1993.1018.

- ↑ Murtagh, Fionn (1983), "A survey of recent advances in hierarchical clustering algorithms" (PDF), The Computer Journal, 26 (4): 354–359, doi:10.1093/comjnl/26.4.354.

-

This article incorporates public domain material from the NIST document: Black, Paul E. "Bounded stack". Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures.

This article incorporates public domain material from the NIST document: Black, Paul E. "Bounded stack". Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures.

Further reading

- Donald Knuth. The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 1: Fundamental Algorithms, Third Edition.Addison-Wesley, 1997. ISBN 0-201-89683-4. Section 2.2.1: Stacks, Queues, and Deques, pp. 238–243.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stack data structure. |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Data Structures/Stacks and Queues |

- Stacks and its Applications

- Stack Machines - the new wave

- Bounding stack depth

- Stack Size Analysis for Interrupt-driven Programs (322 KB)