Stoner (novel)

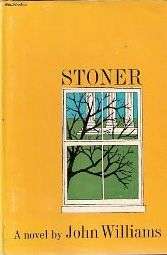

First edition | |

| Author | John Williams |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Viking Press |

Publication date | 1965 |

| Pages | 288 |

| ISBN | 1-59017-199-3 |

| OCLC | 61253892 |

| 813/.54 22 | |

| LC Class | PS3545.I5286 S7 2003 |

Stoner is a 1965 novel by the American writer John Williams. It was reissued in 2003 by Vintage[1] and in 2006 by New York Review Books Classics with an introduction by John McGahern.[2]

Stoner has been categorized under the genre of the academic novel, or the campus novel.[3] Throughout the 200-word prologue and 200-page novel, Stoner follows the undistinguished life and career of William Stoner, an English professor at a Midwestern university.

Plot

The central character, William Stoner, begins as a farm boy in Missouri whose parents send him to the University of Missouri to major in agriculture. After reading Shakespeare's Sonnet 73 and influenced by his instructor, Archer Sloane, Stoner changes his major to literature and pursues a master of arts. After receiving his Ph.D. during World War I, Stoner continues at the university as an assistant professor of English, the position he held for the duration of his career. The novel follows Stoner's undistinguished career and workplace politics, his marriage to Edith, his affair with his colleague Katherine, and his love and pursuit of literature.

Characters

The novel focuses on William Stoner and the central figures in his life. Those who become his enemies are used as tools against him who separate Stoner from his loves. New Yorker contributor Tim Kreider describes their depictions as "evil marked with deformity." [4][5][6]

- William Stoner: The novel's main character, called "Stoner" throughout the book, is a farm boy turned English professor. He uses his love of literature to deal with his unfulfilling home life.

- Edith Stoner: Stoner's wife, a neurotic woman from a strict and sheltered upbringing. Stoner falls in love with the idea of her, but soon realizes that she is bitter and has been long before they were married.

- Grace Stoner: Stoner and Edith's only child. Grace is easily influenced by her mother. Edith keeps Grace away from and against her father as a sort of "punishment" for Stoner, because of the couple's failing relationship.

- Gordon Finch: Stoner's colleague and only real ally and friend. He has known Stoner since their graduate school days and becomes the dean of the college of Arts and Sciences. His affable and outgoing demeanor contrasts that of Stoner.

- David Masters: Stoner's friend from graduate school. He is killed in action during the Great War, but his words have a continuing impact on Stoner's worldview.

- Archer Sloane: Stoner's teacher and mentor growing up. He inspired Stoner to leave agriculture behind and begin studying English literature. He is old and ailing by the time Stoner is hired at the university.

- Hollis Lomax: Sloane's "replacement" at the university. He and Stoner began as friends, but Stoner eventually sees him as an "enemy". Stoner and Lomax do not see eye to eye in their work life. Described as a hunchback.

- Charles Walker: Lomax's crippled mentee, an arrogant and duplicitous young man who uses rhetorical flourish to mask his scholarly ineptitude. Also becomes an enemy to Stoner.

- Katherine Driscoll: A younger teacher, with whom Stoner falls in love and has an affair. University politics and circumstantial differences keep them from continuing a relationship.

Themes

In the novel's introduction, John McGahern says Stoner is a "novel about work." This includes not only traditional work, such as Stoner's life on the farm and his career as a professor, but also the work one puts into life and relationships.[7]

One of the central themes in the novel is the manifestation of passion. Stoner's passions manifest themselves into failures, as proven by the bleak end of his life. Stoner has two primary passions: knowledge and love. According to Morris Dickstein, "he fails at both." [8]

Love is also a widely recognized theme in Stoner. The novel's representation of love moves beyond romance; it highlights bliss and suffering that can be qualities of love. Both Stoner and Lomax discovered a love of literature early in their lives, and it is this love that ultimately endures throughout Stoner's life.[9]

Another of the novel's central themes is the social reawakening, which is closely linked to the sexual reawakening of the protagonist.[10] After the loss of his wife and daughter, Stoner seeks fulfillment elsewhere, beginning the affair with Katherine Driscoll.

Style

John McGahern's Introduction to Stoner and Adam Foulds of The Independent praise Williams' prose for its cold, factual plainness.[9][11] Foulds claims that Stoner has a "flawless narrative rhythm [that] flows like a river."[11] Williams' prose has also been applauded for its clarity, by both McGahern and Charlotte Heathcote of The Daily Express.[6][9] In an interview with the BBC, author Ian McEwan calls Williams' prose "authoritative."[12] Sarah Hampson of The Globe and Mail writes that Williams' "description of petty academic politics reads like the work of someone taking surreptitious notes at dreary faculty meetings."[13] Williams' prose has also been lauded for its precision, making the novel's emotions universally relatable.[6][13]

Background

John Williams had a similar life to that of his character in Stoner. He was an English professor at the University of Denver until he retired in 1985. Like Stoner, he experienced coworker frustrations in the academic world and was devoted to this work, making his novel a reflection of parts of his own life.[14]

Reception

Stoner was initially published in 1965 and sold fewer than 2,000 copies.[15] It was out of print a year later, then reissued in 2003 by Vintage and 2006 by New York Review Books Classics. French novelist Anna Gavalda translated Stoner in 2011, and it became Waterstones' Book of the Year in Britain in 2012. In 2013, sales to distributors tripled.[13] Although Stoner was not a popular novel when it was first published, there were a handful of glowing reviews such as that from The New Yorker on June 12, 1965, in which Williams was praised for creating a character who is dedicated to his work but cheated by the world. Those who gave positive feedback pointed to the truthful voice with which Williams wrote about life's conditions, and they often compared Stoner to his other work, Augustus, in characters and plot direction. One piece of negative criticism came from Williams' own publisher in 1963, who questioned Stoner's potential to gain popularity and become a best seller.[16] Irving Howe and C.P. Snow also gave praise to the novel when it was first published, although sales of the novel did not reflect this positive commentary. It was not until several years later during Stoner’s republication that the book became more well-known. After being re-published and translated into a number of languages, the novel has "sold hundreds of thousands of copies in 21 countries".[17]

Williams' novel is jointly praised for its narrative and stylistic value. In a 2007 review of the recently reissued work, scholar and book critic Morris Dickstein acclaims the writing technique as remarkable and says the novel "takes your breath away".[18][19][20] Bryan Appleyard's review quotes critic D.G. Myers saying that the novel was a good book for beginners in the world of "serious literature".[18] Another critic, author Alex Preston, points out that the novel shows the depressing progression through a person’s life that was written by "the dead hand of realism".[5] In 2010, critic Mel Livatino noted that "[in] nearly fifty years of reading fiction, I have never encountered a more powerful novel—and not a syllable of it sentimental."[21] Writer Steve Almond wrote a review of Stoner in The New York Times Magazine in 2014. Almond claims Stoner focuses on the "capacity to face the truth of who we are in private moments" and questions whether or not any of us are truly able to say we are able to do that. Almond states, "I devoured it in one sitting. I had never encountered a work so ruthless in its devotion to human truths and so tender in its execution."[22] Sarah Hampson of The Globe and Mail sees Stoner as an "antidote" to a 21st-century culture of entitlement. She says that the novel came back to public attention at a time when people feel entitled to personal fulfillment, at the cost of their own morality, and Stoner shows that there can be value even in a life that seems failed.[13] In 2013 it was named Waterstones Book of the Year and The New Yorker called it "the greatest American novel you've never heard of."[23]

Adaptations

A film adaptation of the novel is currently under development by Film4.[24]

References

- ↑ Barnes, Julian. "Stoner: the must-read novel of 2013". the Guardian. Retrieved 2015-11-02.

- ↑ John Williams, Stoner, New York Review Books, New York, 2003.

- ↑ The Academic Novel and the Academic Ideal: John Williams' Stoner. Steve Wiegenstein. The McNeese Review. 1990.

- ↑ "The Greatest American Novel You've Never Heard Of". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2015-11-02.

- 1 2 "Stoner by John Williams". Alex Preston. Retrieved 2015-10-28.

- 1 2 3 "Book Review: Stoner by John Williams". Express.co.uk. Retrieved 2015-10-28.

- ↑ Williams, John. Stoner. New York Review of Books. pp. xii. ISBN 978-1-59017-199-8.

- ↑ The Inner Lives of Men. Morris Dickstein. The New York Times. June 17, 2007

- 1 2 3 McGahern, John. Introduction. Stoner. By John Williams. New York: New York Review Books, 2003. Print.

- ↑ The Academic Novel and the Academic Ideal: John Williams' Stoner. Steve Wiegenstein. The McNeese Review. 1990.

- 1 2 "Stoner, By John Williams: Book of a lifetime". The Independent. Retrieved 2015-10-28.

- ↑ "Novelist McEwan praises Stoner - BBC News". BBC News. Retrieved 2015-10-28.

- 1 2 3 4 "Stoner: How the story of a failure became an all-out publishing success". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2015-10-26.

- ↑ David, Milofsky (2007). "John Williams deserves to be read today". Denver Post.

- ↑ "Literary rebirth". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2015-11-02.

- ↑ Barnes, Julian. "Stoner: the must-read novel of 2013". the Guardian. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ↑ Ellis, Bret Easton. "John Williams's great literary western | Bret Easton Ellis". the Guardian. Retrieved 2015-10-28.

- 1 2 "Bryan Appleyard » Blog Archive » Stoner: The Greatest Novel You Have Never Read". bryanappleyard.com. Retrieved 2015-10-28.

- ↑ Dickstein, Morris (2007-06-17). "The Inner Lives of Men". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2015-10-28.

- ↑ "The Inner Lives of Men," by Morris Dickstein, New York Times, June 17, 2007

- ↑ Mel Livatino "A Sadness Unto the Bone - John Williams's Stoner in The Sewanee Review, 118:3, p. 417

- ↑ Almond, Steve (2014-05-09). "You Should Seriously Read 'Stoner' Right Now". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2015-10-28.

- ↑ "Stoner by John Williams awarded Waterstones book prize". BBC. 3 December 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ↑ "Cannes: Blumhouse, CMG, Film4 Team on 'Stoner' (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved 2015-10-28.

External links

- Discussion of "Stoner" and the techniques of literary realism

- Sonnet 73 with notes, pictures and a summary at shakespeare-navigators.com