String theory landscape

| String theory |

|---|

|

| Fundamental objects |

| Perturbative theory |

| Non-perturbative results |

| Phenomenology |

| Mathematics |

|

Theorists

|

The string theory landscape refers to the huge number of possible false vacua in string theory.[1] The large number of theoretically allowed configurations has prompted suggestions that certain physical mysteries, particularly relating to the fine-tuning of constants like the cosmological constant or the Higgs boson mass, may be explained not by a physical mechanism but by assuming that many different vacua are physically realized.[2] The anthropic landscape thus refers to the collection of those portions of the landscape that are suitable for supporting intelligent life, an application of the anthropic principle that selects a subset of the otherwise possible configurations.

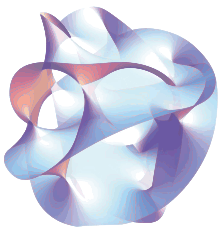

In string theory the number of false vacua is thought to be somewhere between 1010 to 10500.[1] The large number of possibilities arises from different choices of Calabi–Yau manifolds and different values of generalized magnetic fluxes over different homology cycles. If one assumes that there is no structure in the space of vacua, the problem of finding one with a sufficiently small cosmological constant is NP complete,[3] being a version of the subset sum problem.

Anthropic principle

The idea of the string theory landscape has been used to propose a concrete implementation of the anthropic principle, the idea that fundamental constants may have the values they have not for fundamental physical reasons, but rather because such values are necessary for life (and hence intelligent observers to measure the constants). In 1987, Steven Weinberg proposed that the observed value of the cosmological constant was so small because it is impossible for life to occur in a universe with a much larger cosmological constant.[4] In order to implement this idea in a concrete physical theory, it is necessary to postulate a multiverse in which fundamental physical parameters can take different values. This has been realized in the context of eternal inflation.

Bayesian probability

Weinberg (1987) attempted to predict the magnitude of the cosmological constant based on probabilistic arguments. Other attempts have been made to apply similar reasoning to models of particle physics.[5]

Such attempts are based in the general ideas of Bayesian probability; interpreting probability in a context where it is only possible to draw one sample from a distribution is problematic in frequentist probability but not in Bayesian probability, which is not defined in terms of the frequency of repeated events.

In such a framework, the probability of observing some fundamental parameters is given by,

where is the prior probability, from fundamental theory, of the parameters and is the "anthropic selection function", determined by the number of "observers" that would occur in the universe with parameters .

These probabilistic arguments are the most controversial aspect of the landscape. Technical criticisms of these proposals have pointed out that:

- The function is completely unknown in string theory and may be impossible to define or interpret in any sensible probabilistic way.

- The function is completely unknown, since so little is known about the origin of life. Simplified criteria (such as the number of galaxies) must be used as a proxy for the number of observers. Moreover, it may never be possible to compute it for parameters radically different from those of the observable universe.

Simplified approaches

Tegmark et al. have recently considered these objections and proposed a simplified anthropic scenario for axion dark matter in which they argue that the first two of these problems do not apply.[6]

Vilenkin and collaborators have proposed a consistent way to define the probabilities for a given vacuum.[7]

A problem with many of the simplified approaches people have tried is that they "predict" a cosmological constant that is too large by a factor of 10–1000 (depending on one's assumptions) and hence suggest that the cosmic acceleration should be much more rapid than is observed.[8][9][10]

Criticism

Although few dispute the idea that string theory appears to have an unimaginably large number of metastable vacua, the existence - meaning and scientific relevance of the anthropic landscape - remain highly controversial. Prominent proponents of the idea include Andrei Linde, Sir Martin Rees and especially Leonard Susskind, who advocate it as a solution to the cosmological-constant problem. Opponents, such as David Gross, suggest that the idea is inherently unscientific, unfalsifiable or premature. A famous debate on the anthropic landscape of string theory is the Smolin–Susskind debate on the merits of the landscape.

The term "landscape" comes from evolutionary biology (see Fitness landscape) and was first applied to cosmology by Lee Smolin in his book.[11] It was first used in the context of string theory by Susskind.

There are several popular books about the anthropic principle in cosmology.[12] The authors of two physics blogs are opposed to this use of the anthropic principle.[13]

See also

References

- 1 2 The most commonly quoted number is of the order 10500. See M. Douglas, "The statistics of string / M theory vacua", JHEP 0305, 46 (2003). arXiv:hep-th/0303194; S. Ashok and M. Douglas, "Counting flux vacua", JHEP 0401, 060 (2004).

- ↑ L. Susskind, "The anthropic landscape of string theory", arXiv:hep-th/0302219.

- ↑ Frederik Denef; Douglas, Michael R. (2006). "Computational complexity of the landscape". Annals of Physics. 322 (5): 1096–1142. arXiv:hep-th/0602072

. Bibcode:2007AnPhy.322.1096D. doi:10.1016/j.aop.2006.07.013.

. Bibcode:2007AnPhy.322.1096D. doi:10.1016/j.aop.2006.07.013. - ↑ S. Weinberg, "Anthropic bound on the cosmological constant", Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 2607 (1987).

- ↑ S. M. Carroll, "Is our universe natural?" (2005) arXiv:hep-th/0512148 reviews a number of proposals in preprints dated 2004/5.

- ↑ M. Tegmark, A. Aguirre, M. Rees and F. Wilczek, "Dimensionless constants, cosmology and other dark matters", arXiv:astro-ph/0511774. F. Wilczek, "Enlightenment, knowledge, ignorance, temptation", arXiv:hep-ph/0512187. See also the discussion at .

- ↑ See, e.g. Alexander Vilenkin (2006). "A measure of the multiverse". Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical. 40 (25): 6777–6785. arXiv:hep-th/0609193

. Bibcode:2007JPhA...40.6777V. doi:10.1088/1751-8113/40/25/S22.

. Bibcode:2007JPhA...40.6777V. doi:10.1088/1751-8113/40/25/S22. - ↑ Abraham Loeb (2006). "An observational test for the anthropic origin of the cosmological constant". JCAP. 0605: 009. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Jaume Garriga & Alexander Vilenkin (2006). "Anthropic prediction for Lambda and the Q catastrophe". Prog. Theor.Phys. Suppl. 163: 245–57. arXiv:hep-th/0508005

. Bibcode:2006PThPS.163..245G. doi:10.1143/PTPS.163.245. (subscription required (help)).

. Bibcode:2006PThPS.163..245G. doi:10.1143/PTPS.163.245. (subscription required (help)). - ↑ Delia Schwartz-Perlov & Alexander Vilenkin (2006). "Probabilities in the Bousso-Polchinski multiverse". JCAP. 0606: 010. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ L. Smolin, "Did the universe evolve?", Classical and Quantum Gravity 9, 173–191 (1992). L. Smolin, The Life of the Cosmos (Oxford, 1997)

- ↑ L. Susskind, The cosmic landscape: string theory and the illusion of intelligent design (Little, Brown, 2005). M. J. Rees, Just six numbers: the deep forces that shape the universe (Basic Books, 2001). R. Bousso and J. Polchinski, "The string theory landscape", Sci. Am. 291, 60–69 (2004).

- ↑ Lubos Motl's blog criticized the anthropic principle and Peter Woit's blog frequently attacks the anthropic string landscape.

External links

- String landscape; moduli stabilization; flux vacua; flux compactification on arxiv.org

- Cvetič, Mirjam; García-Etxebarria, Iñaki; Halverson, James (March 2011). "On the computation of non-perturbative effective potentials in the string theory landscape". Fortschritte der Physik. 59 (3-4): 243–283. arXiv:1009.5386

. Bibcode:2011ForPh..59..243C. doi:10.1002/prop.201000093.

. Bibcode:2011ForPh..59..243C. doi:10.1002/prop.201000093.