Thammasat University massacre

| Thammasat University massacre | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Thammasat University and Sanam Luang in Bangkok, Thailand |

| Date | 6 October 1976 |

| Target | Student protesters |

| Deaths | 46 (official); more than 100 (unofficial) |

Non-fatal injuries | 167 (official) |

| Perpetrators |

Royal Thai Armed Forces Royal Thai Police Village Scouts Nawaphon Red Gaur |

The Thammasat University massacre (in Thailand known simply as "the 6 October event", Thai: เหตุการณ์ 6 ตุลา rtgs: het kan hok tula) was an attack by Thai state forces and far-right paramilitaries on student protesters on the campus of Thammasat University and the adjacent Sanam Luang Square in Bangkok, Thailand on 6 October 1976. Prior to the massacre, four to five thousand students from various universities had demonstrated for more than a week against the return to Thailand from Singapore of former military dictator Thanom Kittikachorn.

A day before the massacre, the Thai press reported on a play staged by student protesters the previous day, which allegedly featured the mock hanging of Crown Prince Vajiralongkorn. In response to this rumored outrage, military and police as well as paramilitary forces surrounded the university. Just before dawn on 6 October, the attack on the student protesters began and continued until noon. To this day, the number of casualties remains in dispute between the Thai government and survivors of the massacre. According to the government, 46 died in the killings, with 167 wounded and 3,000 arrested. Many survivors claim that the death toll was well over 100.[1]:236

Massacre

Immediate causes

The 14 October 1973 uprising overthrew the unpopular Thanom regime and saw him flee Thailand together with General Praphas Charusathien and General Narong Kittikachorn, collectively known as the "three tyrants".[1]:209 Growing unrest and instability from 1973 to 1976, as well as the fear of communism from neighboring countries spreading to Thailand and threatening the interests of the monarchy and the military, convinced the latter to bring former leaders Thanom and Praphas back to Thailand to control the situation. In response to Praphas's return on 17 August, thousands of students demonstrated at Thammasat University for four days until a clash with Red Gaur and Nawaphon toughs left four dead.[1]:233 On 19 September, Thanom returned to Thailand and headed straight from the airport to Wat Bowonniwet Vihara, where he was ordained as a monk in a private ceremony. Massive anti-Thanom protests broke out as the government faced an internal crisis after Prime Minister Seni Pramoj's attempt to tender his resignation was rejected by the Thai Parliament. On 25 September, in Nakhon Pathom, west of Bangkok, two activists putting up anti-Thanom posters were beaten to death and hung from a wall, an outrage that was soon established to be the work of Thai police.[1]:235 A dramatization of this hanging was staged by student protesters at Thammasat University on 4 October. Deliberately or unfortunately, the student at the end of the garrote bore a resemblance to Crown Prince Vajiralongkorn.[1]:235 The following day, as Seni struggled to put together his cabinet, the newspaper Dao Siam published a photograph of the mock hanging on its front page.[2]:90 With the tacit approval of King Bhumibol, announcers on army-controlled radio stations accused the student protesters of lèse-majesté and mobilized the king's paramilitary forces, the Village Scouts, Nawaphon, and Red Gaurs to "kill the communists".[1]:235 At dusk on 5 October, some 4,000 people from these paramilitary forces as well as military and police personnel gathered outside Thammasat University where student protesters had been protesting for weeks. This set the scene for the Thammasat University massacre the following day.[2]:90 ..

Massacre

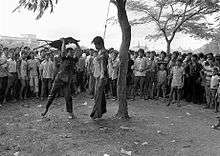

At dawn on 6 October, the military and the police as well as the three paramilitary forces blocked exits from the university and began shooting into the campus, using M-16s, carbines, pistols, grenade launchers, and even armor-piercing recoilless rifles.[1]:235-236[5] Prevented from leaving the campus or even sending wounded to the hospital, the students begged for a ceasefire. The attacks continued.[1]:236 The actors in the mock hanging had already turned themselves in to Seni at the prime minister's office.[1]:236 When one student came out to surrender, he was shot and killed.[1]:236 After a free-fire order was issued by the Bangkok police chief, the campus was stormed, with Border Patrol Police leading the attack.[1]:236 Students diving into the Chao Phraya River were shot at by naval vessels while others who surrendered, lying down on the ground, were picked up and beaten, many to death.[1]:236 Some were hung from trees and beaten,[6] others were set afire. Female students were raped, alive and dead, by police and Red Gaurs.[1]:236 The massacre continued for several hours, and was only halted at noon by a rainstorm.[1]:236

Immediate aftermath

On the afternoon of 6 October after the massacre, the major factions of the military which formed the general staff agreed in principle to overthrow Seni, a plot that King Bhumibol was well aware of and approved, which in turn ensured the success of the coup-makers.[2]:91 Later that night, Admiral Sangad Chaloryu, the newly appointed supreme commander, announced that the military, under the name of the "National Administrative Reform Council" (NARC) had seized power to "prevent a Vietnamese-backed communist plot" and to preserve the "Thai monarchy forever".[2]:91 The king appointed the anti-communist and royalist judge Thanin Kraivichien to lead a government that was composed of those who were loyal to the king. Thanin and his cabinet restored the repressive climate which had existed before 1973.[2]:91

Significance

Return of bureaucratic polity

Over a period of forty years from 1932 when the absolute monarchy was abolished, until 1973 when military rule was overthrown in favor of democracy, military officers and civil servants held sway in Thai politics and dominated the government, with King Bhumibol serving as the ceremonial head of state in accordance with his role as a constitutional monarch established by the 1932 constitution. The Thai political system was known as a "bureaucratic polity" which was dominated by the military and civilian bureaucrats.[7] The massacre disproved the argument that the bureaucratic polity was on the retreat as the military came to play a central role once more in Thai politics, a situation that would continue throughout the 1970s and 1980s until the 1988 general election when all seats were democratically elected, including that of the prime minister, who from 1976 to 1988 was appointed by the king.

Withdrawal symptoms

Following in the footsteps of previous military strongmen like Plaek Phibunsongkhram and Sarit Thanarat, Thanom became prime minister in 1963 following Sarit's death. He oversaw a massive influx of financial aid from the United States and Japan, fuelling the Thai economy, as well as increasing American cultural influence. But by the early-1970s, the US was withdrawing its troops from Indochina. In such a context, the Thai middle class and petty bourgeoisie who had supported student efforts in 1973 to topple the Thanom regime were more a product of their immediate history than devotees of democracy.[8]:18 They lacked political experience and so had no real idea of the consequences of ending the dictatorship. The regime was simultaneously blamed both for failing to exact fuller commitments from its allies and for excessive subservience to Washington.[8]:18 The support given by the Thai middle class and petty bourgeoisie to the 1973 student protests was not an unconditional stamp of approval for democratic processes and the chaos that followed. The "chaotic democracy" from 1973 to 1976 was seen as having threatened the economic interests of the middle class and petty bourgeoisie who favored stability and peace above democracy. In light of this, while they supported the mass demonstrations against the Thanom regime leading up to the uprising on 14 October 1973, they turned their backs on democracy, hence Anderson's use of the phrase "withdrawal symptoms", and welcomed the return to dictatorship on 6 October 1976, heralding the end of the period of chaotic democracy.

King Bhumibol's role

Overview

King Bhumibol had supported student protesters in their demonstrations in 1973 that led to the downfall of the Thanom regime and resulted in the period of "chaotic democracy" from 1973 to 1976. By 1976, he had turned against the students and, according to many scholars, played a crucial, if not the most important, role in bringing about the massacre and a return to military rule after a three-year flirtation with democracy. There were two reasons for this about-face. First, Thailand's neighbors either were facing communist insurgencies or had fallen to communist rule and become communist countries. The US was withdrawing its military presence from the region. The pivotal year in the trajectory of the king's involvement in politics was 1975. South Vietnam fell to the communists and the Communist Party of Vietnam was able to unify the country under its rule and drive out the US. In Cambodia, the communist Khmer Rouge took over the capital Phnom Penh and began a reign of terror that would only end in 1979. The 1975 incident that arguably shook the Thai monarchy to the core was the overthrow by the Lao People's Revolutionary Party of the Lao Royal Family, to which the Thai monarchy traditionally had cultural and historical ties. Second, the period of chaotic democracy brought instability and chaos as demonstrations, strikes, and protests took place much more frequently. They threatened the economic interests of the monarchy managed by the Crown Property Bureau, which favored a stable and peaceful economic environment that would allow its businesses to thrive.

King Bhumibol wielded his influence through a "network monarchy" that was centered on Privy Council President Prem Tinsulanonda. One of the main features of the network monarchy was that the monarch intervened actively in political developments, largely by working through proxies such as privy councillors and trusted military figures.[9] This network monarchy suggests that, contrary to the popular belief that the king was a constitutional monarch and above politics, rather he had been intimately involved in Thai politics and had often intervened in order to secure his political and economic interests. The instability brought about by the student protesters until 1976 as well as the growing specter of communist threat in the region, especially after the "domino effect" where Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos fell in succession to the communists, convinced King Bhumibol to see the protesters as a threat to his rule. The Thai state and its politicians subsequently branded these students, as well as workers and farmers, as "communists" and a "fifth column for the Communist Party of Thailand (CPT) and North Vietnam."[1]:220 In reality, there was little evidence for the claim that protesters, including students protesting at Thammasat University, were communists. While the CPT had grown in strength, they were far from a unified force and they appealed to peasants by focusing on social injustices while avoiding attacking the monarchy and Buddhism. Their gains were fuelled more by the government's alienation of the peasantry.[1]:220 This suggests that the term "communists" was applied very liberally and indiscriminately and more often than not, deliberately, to those who were deemed to be the sources of instability that threatened the monarchy and the king. In the Thai state's view, communism was simply the enemy of the nation, religion (Buddhism), and monarchy, and a sworn enemy of "Thainess".[10]:169-170 One of the more persistent counterinsurgency strategies was to link socialists, communists, and the Left to external threats.[10]:169-170 In order to deal effectively with the "communist" threat that would undermine his rule and status, in addition to deploying governmental forces such as the Thai military and police, King Bhumibol, through his network monarchy, also encouraged three paramilitary forces—the Village Scouts, Nawaphon, and Red Gaurs—to use violence against protesters from 1973 to 1976. This culminated in the Thammasat massacre.

Village Scouts

The Village Scouts organization was a national paramilitary group sponsored by the King and Queen of Thailand since 1972 in order to promote national unity against threats to Thai independence and freedom, particularly against "communism".[11]:407 The movement was set up explicitly to protect the monarchy from communism. It focused on the central features of Thai identity: love of play, deep respect for the king and religion (Buddhism), and for ethnic Thai "specialness".[11]:413 The king was held to be central to the Thai nation, to be protected at all costs, alongside the nation and religion, forming the Thai nationalist shibboleth, "nation, religion, king". The Village Scouts presence provided continuous proof of militant political support for nation-religion-king beyond the Bangkok upper classes, among the "establishments" of provincial capitals, small towns, and villages. It helped to legitimize private, localized repression of protesting peasants and student activists as essential for the preservation the status quo.[8] During the period 1973–1976, Village Scout membership rose to tens of thousands, almost all in rural, CPT-influenced Thailand. After an Internal Security Operations Command (ISOC) takeover, the Village Scouts metamorphosed into a fascist-style mass political movement that would play a major role in the ensuing massacre.[1]:224

Nawaphon

Nawaphon was an ISOC operation organized in 1974. It was composed of mainly low-level government functionaries and clerks, petite bourgeoisie, rural village and communal headmen, as well as a number of monks.[12]:151 The name "Nawaphon" means "nine strengths", a reference to either the Chakri Ninth Reign (King Bhumibol)[1]:225 or the nine points of Nawaphon's program to preserve Thai nationalism.[12]:151 The aim of Nawaphon was to protect the king from threats like communism. A key figure of the movement was the monk, Kittivudho Bhikkhu, who became its leader in 1975. In a June 1976 interview he was asked if killing leftists or communists would produce demerits or negative karma, he said that such killing would not be demeriting because, "...whoever destroys the nation, the religion or the monarchy, such bestial types are not complete persons. Thus, we must intend not to kill people but to kill the Devil; this is the duty of all Thai".[12]:153 In 1967, he established Jittiphawan College. It was inaugurated by King Bhumibol and Queen Sirikit who returned regularly even after Kittivudho began to make incendiary speeches about the need to deal with student protesters and communists.[1]:225 This suggests a close relationship between the Nawaphon movement and the royal family. Employing the slogan that "killing communists is not demeritorious", Kittivudho encouraged the killings of alleged communists from 1973 to 1976 and injected militant Buddhism into the Thai body politic, eventually inciting his followers to commit violence at Thammasat University on 6 October. Earlier, Nawaphon was responsible for the killing of more than 20 prominent farmer activists in 1975.[1]:226 The murders were an attempt to negate the farmers' new-found political agency and, by so doing, return them to their pre-October 1973 state of relative repression.[13] The assassinations of farmer activists were part of the state campaign to suppress any potential threat to the king's rule, sanctioned and encouraged by the king as an integral part of his anti-communist purge.

Red Gaurs

The Red Gaurs were ex-mercenaries and men discharged from the military for disciplinary infractions mixed with unemployed vocational school graduates, high-school dropouts, idle street corner boys, and slum toughs.[8] In the early-1970s, potential recruits found themselves in dire economic straits, unable to obtain employment, and thus were easy targets of anti-student and anti-worker propaganda.[8] Their grievances were exploited by the state, notably the king's network, and their anger directed towards student protesters. They were recruited not on the basis of ideological commitment, but rather by promises of high pay, abundant liquor, brothel privileges, and the lure of public notoriety.[8] Unlike the Village Scouts and the Nawaphon, the motivation of the Red Gaurs was more sociological than ideological.

Royal family involvement

King Bhumibol and the royal family took part frequently in Village Scout activities and attended ceremonies at Kittivudho's college and Red Gaur training camps, thus illustrating their close ties with these three paramilitary forces.[1]:227 While all three forces differed in their nature, they were united by their allegiance to the king and, concomitantly, their hatred of communists. These paramilitary forces would subsequently be mobilized to attack the student protesters at Thammasat University to end their weeks-long protests.

Remembrance

The Thammasat University massacre continues to be a "...scar on the Thai collective psyche..."[14] The government has remained silent over its role, and that of the king, in the killing of student protesters. This silence is deeply embedded in a culture of impunity.[15] In an analysis of the two amnesty laws passed in relation to the massacre, Thailand scholar Tyrell Haberkorn argues that they first created and then consolidated impunity for the coup and the massacre that preceded it.[16]:47 The first amnesty law, passed on 24 December 1976, legalized the coup and prevented those who seized power on the evening of 6 October from being held accountable.[16]:44 The second amnesty law, passed on 16 September 1978, freed eighteen student activists still undergoing criminal prosecution and dismissed the charges against them.[16]:44 The "hidden transcripts" of the two amnesties for massacre and coup that followed reveal the careful, calculated legal moves taken to protect those who were behind them.[16]:64 Despite the rhetoric in the streets and on the radio about the need to protect the nation, the coup and the massacre that preceded it unsettled some inside the state, perhaps because they were aware of the extra-legal status of the massacre, perhaps because they worried about their own culpability, and perhaps because they were aware that the violations in need of amnesty were not only those of the criminal code but of the more basic code of being human.[16]:64-65 Thus, both amnesty laws sought to produce impunity for state violence, particularly the king's involvement. There been no state investigation into the violence and this impunity is both cause and effect of the silence, ambivalence, and ambiguity surrounding the event for both those who survived it and Thai society.[16]:46

Thai scholar Thongchai Winichakul, one of the student protesters who was jailed for his participation in the protests at Thammasat University, argues that the clearest evidence of the evasive public memories of the uprisings and massacre are the names the events have come to be known by, and the most conspicuous site of contested memories is the controversy over the memorial for the events.[17]:265 The massacre continues to be known in Thailand by the deliberately ambiguous term "6 October event". Thongchai argues that this non-committal name is loaded with many unsettled meanings, which imply the absence of any commitment and obscures the past because it is too heavily loaded with contesting voices, placing the massacre on the edge between recognizability and anonymity, between history and the silenced past, and between memory and forgetfulness.[17]:266 Thus, in "remembering" it, its nomenclature carries overt political significance that continues to reverberate in present-day Thai politics, particularly in relation to the role played by the state and King Bhumibol in the attack on student protesters.

The commemoration in 1996 represented a significant break in the silence. Yet, during the commemoration, what happened twenty years earlier was retold innumerable times, though without any reference to the undiscussable parts of that history.[17]:274 There was also no reaction, not even any comment, from the military or any conservative organization.[17]:274 More importantly, the denunciation of state crime avoided imputing blame to any specific individual and the victims' self-sacrifice for society's sake was honored.[17]:274-275 The role played by King Bhumibol in inciting the military and police and paramilitary forces to attack the student protesters was not mentioned so as not to target the king as an "individual". Yet, this could also be interpreted as an attempt by the state to whitewash history by wishing away parts that it did not want the public to know or remember. In addition, by emphasizing the theme of healing and reconciliation in the remembrance, the Thai state, and by implication the king, have sought to make clear that the commemoration had no interest in and would not be involved in any talk of retribution.[17]:274

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Handley, Paul M (2006). The King Never Smiles; A Biography of Thailand's Bhumibol Adulyadej. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10682-3. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mallet, Marian (1978). "Causes and Consequences of the October '76 Coup". Journal of Contemporary Asia. 8 (1). Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ↑ Rithdee, Kong (30 September 2016). "In the eye of the storm". Bangkok Post. Post Publishing. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ↑ Supawattanakul, Kritsada (6 October 2016). "Coming to terms with a brutal history" (Opinion). Bangkok Post. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ↑ "OCT. 6 MASSACRE: THE PHOTOGRAPHER WHO WAS THERE". Khaosod English. Associated Press (AP). 5 October 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ↑ Rojanaphruk, Pravit (5 October 2016). "THE WILL TO REMEMBER: SURVIVORS RECOUNT 1976 THAMMASAT MASSACRE 40 YEARS LATER". Khaosod English. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ↑ Riggs, Fred (1976). "The Bureaucratic Polity as a Working System". In Clark Neher, ed., Thailand: From Village to Nation. Cambridge: Schenkman Books, pp. 406-424.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Anderson, Ben (Jul–Sep 1977). "Withdrawal Symptoms: Social and Cultural Aspects of the October 6 Coup" (PDF). Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars. 9 (3): 13–18. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ↑ McCargo, Duncan (2005). "Network Monarchy and Legitimacy Crises". The Pacific Review, Vol. 18, No. 4, p. 501.

- 1 2 Winichakul, Thongchai (1994). Siam Mapped: A History of the Geo-Body of Siam. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

- 1 2 Muecke, Marjorie (1980). "The Village Scouts of Thailand". Asian Survey, Vol. 20, No. 4.

- 1 2 3 Keyes, Charles (1978). "Political Crisis and Militant Buddhism in Contemporary Thailand". In Bardwell L. Smith, ed., Religion and Legitimation of Power in Thailand, Laos, and Burma. Chambersburg: Anima Books.

- ↑ Haberkorn, Tyrell (2009). "An Unfinished Past: Assassination and the 1974 Land Rent Control Act in Northern Thailand". Critical Asian Studies, Vol. 41, No. 1, p. 28.

- ↑ Corben, Ron (5 October 2016). "Thailand to Mark 40th Anniversary of Bloody 1976 Massacre". VOA News. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ↑ Editor2 (3 October 2016). "Culture of impunity and the Thai ruling class: Interview with Puangthong Pawakapan". Prachatai English. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Haberkorn, Tyrell (2015). "The Hidden Transcript of Amnesty: The 6 October 1976 Massacre and Coup in Thailand". Critical Asian Studies, Vol. 47, No. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Thongchai Winichakul (2002). "Remembering/ Silencing the Traumatic Past". In Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles F. Keyes eds., Cultural Crisis and Social Memory: Modernity and Identity in Thailand and Laos. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

External links

13°45′21.07″N 100°29′27.16″E / 13.7558528°N 100.4908778°ECoordinates: 13°45′21.07″N 100°29′27.16″E / 13.7558528°N 100.4908778°E