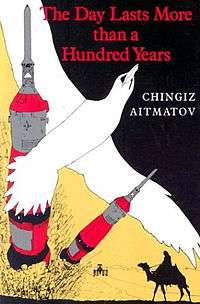

The Day Lasts More Than a Hundred Years

| |

| Author | Chinghiz Aitmatov |

|---|---|

| Original title | И дольше века длится день |

| Translator | F. J. French |

| Country | Soviet Union |

| Language | Russian |

| Genre | Science fiction novel |

| Publisher |

Novy Mir (as series) Indiana University Press (as Book) |

Publication date | 1980 (English edition September 1983) |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 368 pp |

| ISBN | 0-253-11595-7 |

| OCLC | 255105725 |

| 891.73/44 19 | |

| LC Class | PG3478.I8 D613 1983 |

The Day Lasts More Than a Hundred Years (Russian: И дольше века длится день, "And longer than a century lasts a day"), originally published in Russian in the Novy Mir literary magazine in 1980, is a novel written by the Kyrgyz author Chinghiz Aitmatov.

The title of the novel

In an introduction written in 1990, during perestroika, the author wrote that the original title was The Hoop ("Обруч"), which was rejected by censors. The title The Day Lasts More Than a Hundred Years, taken from the poem "Unique Days" ("единственные дни") by Boris Pasternak, used for the magazine version (Novy Mir, #11, 1980), was also criticized as too complicated, and the first "book-size" version of the novel was printed in Roman-Gazeta in a censored form under the title The Buranny Railway Stop (Буранный полустанок).

Introduction

The novel takes place over the course of a day, which encompasses the railman Burranyi Yedigei's endeavor to bury his late friend, Kazangap, in the cemetery Ana-Beiit ("Mother's Grave"). Throughout the trek, Yedigei recounts his personal history of living in the Sary-Ozek steppes along with pieces of Kazakh folklore. The author explains the term "Saryozeks" as "Middle Lands of Yellow Stepes". Sary-Ozek (or Russified form "Sarozek", used interchangeably in the novel) is also the name of a (fictional) cosmodrome.

Additionally, there is a subplot involving two cosmonauts, one American and one Soviet, who make contact with an intelligent extraterrestrial life form and travel to the planet Lesnaya Grud' ("The Bosom of the Forest") while on a space station run co-operatively by the United States and the Soviet Union. The location of the Soviet launch site, Sarozek-1, near Yedigei's railway junction, intertwines the subplot with the main story.

Plot summary

The novel begins with Yedigei learning about the death of his longtime friend, Kazangap. All of Kazangap's crucial relatives have been forewarned of his impending death, and it is decided to set off to bury him the next day. To the consternation of his son, Sabitzhan, who is indifferent toward his father's burial, it is decided to travel across the Sarozek to the Ana-Beiit cemetery in order to bury Kazangap. The procession promptly leaves the next morning, and experiences that took place throughout Yedigei's lifetime, as well as various Sarozek legends, are recollected.

Initially, Yedigei recalls how he had fought in World War II but had been dismissed from duty due to shell shock. As a result, he was sent to work on the railway. Through his work, he met Kazangap, who convinced him to move to what would become his permanent home, the remote Boranly-Burannyi junction, from which he gained his namesake. Kazangap and Yedigei become dear friends, and Kazangap eventually gives Yedigei the gift of a camel, named Karanar, which becomes legendary across the Sarozek because of its strength and vitality.

At the end of 1951, Abutalip and Zaripa Kuttybaev move to Boranly-Burranyi junction with their two young sons. They initially have a hard time adjusting to living on the Sarozek because of the harsh environment; however, they eventually become adjusted. Before relocating, both had been school teachers. Abutalip also fought in the war and had been taken prisoner by the Germans, but he escaped and fought with the Yugoslav partisan army. Nevertheless, upon his return to the Soviet Union he still retained the stigma of having been a prisoner of war and was often relocated because of political reasons.

To leave a personal account of his experiences for his children and also to maintain his faculties amid the desolate Sarozek, Abutalip takes to writing about his time as a prisoner of war, his escape, and fighting for the partisans; he also records the various legends told to him by Yedigei. Unfortunately for him, these activities are discovered during a routine inspection of the junction and reported to higher authorities. The denizens of Boranly-Burannyi and Abutalip are interrogated by the tyrannical Tansykbaev, and he is deemed counterrevolutionary. In due Soviet process, he is taken away and unheard of for a long time. Later, Kazangap travels to the nearby Kumbel' to visit his son. There he finds a letter meant to inform Zaripa of Abutalip's death, but thinks it best to merely tell her that she has a letter rather to inform her of its contents. Yedigei later accompanies Zaripa to Kumbel' in order to receive the letter; coincidentally, Joseph Stalin dies on the same day, but Zaripa was too overcome with grief to pay notice to the news.

Zaripa decides that it is best to forestall conveying the news of Abutalip's death to her children. Yedigei thereafter becomes the paternal figure in her children's lives and grows to love them more than his own daughters. Abutalip's last request was for Yedigei to tell his sons about the Aral Sea, so Yedigei spends much time telling them about his former occupation as a fisherman. As a result of his frequent reminiscing, Yedigei recalls the time he had to catch a golden sturgeon to quell the desires of his wife, Ukubala's, unborn child but decides not to share it. He eventually becomes fond of Zaripa from spending so much time with her and her children, but she does not return his affection and moves away one day when Yedigei travels to another junction to fetch his wandering camel. In consequence, Yedigei projects his anger onto Karanar by maiming him until he runs away again, only to later return famished and dilapidated.

Years later, after internal reforms within the Soviet Union, Yedigei pressures the government to inquire into Abutalip's death in order to clear the names of his sons. Abutalip is declared "rehabilitated," and Yedigei also learns that Zaripa has remarried and has once more begun working as a school teacher.

Near the end of the story, the group that set out to bury Kazangap has nearly reached the Ana-Beiit cemetery. However, they are hindered in their journey by a barbed wire fence erected in the middle of their route. Resolved to go around it, they travel along it toward another road only to reach a check-point manned by a young soldier. To their dismay, they are told that access beyond the fence is prohibited, but the soldier calls his superior to see if an exception can be made. It is then that Yedigei learns that the superior is named Tansykbaev but discovers that this is a different man from the one previously known. However, the new Tansykbaev is also encrusted in a patina of hierarchical obedience and interpersonal tyranny; unmoved by the procession's request, he denies them entry and also informs them that the Ana-Beiit cemetery is to be leveled in the future.

During their return, everybody in the group, with the exception of Kazangap's son, Sabitzhan, decides that it would be against tradition to return from a burial with a body. They decide to bury Kazangap near a precipice on the Sarozek. Yedigei, most adamantly, makes them promise to bury him next to Kazangap since he is the oldest and the most likely to die next.

Everybody leaves after the burial, but Yedigei remains with Karanar and his dog, Zholbars, to ruminate over the day's circumstances. He decides to return to the check-point in order to vocalize his anger at the guard, but a series of rockets are launched into space from within the fenced area before he reaches the check-point, sending Yedigei, Zholbars, and Karanar running off into the Sarozek.

Subplot summary

Shortly after learning the news of Kazangap's death, Yedigei observes a rocket launching from the launch site north of the Boranly-Burranyi junction. Launches, though infrequent, are not unusual to Yedigei, but this one in particular is because he had no prior knowledge of it. Generally, such occasions heralded pompous celebration, but this one had not.

This launch, and the circumstances surrounding it, have been kept secret from the public, and an American launch from Nevada occurs at the same time. Both are destined for the joint Soviet-American space station, Parity, currently orbiting the Earth. There were already two cosmonauts on board the Parity space station before the launch; however, they had mysteriously curtailed all contact with the aircraft carrier Convention, afloat between San Francisco and Vladivostok, which serves as a base of operations for the Soviets and Americans.

Once they arrive, the two cosmonauts sent to Parity discover that their predecessors have disappeared completely. Before leaving, they left a note stating that they had made contact with intelligent life from the planet Lesnaya Grud'. Together, they decided to keep their findings private out of fear for the political turmoil that might occur. The inhabitants of Lesnaya Grud' had traveled to Parity and transported the two cosmonauts to their home planet. From there, the cosmonauts send a transmission back to Parity describing the planet. It has a much larger population than Earth, nobody has any concept of war, and there is an established and functional world government. Furthermore, Lesnaya Grud' suffers from the problem of "internal withering," where portions of the planet turn to uninhabitable desert. Although this problem will not be critical for many millions of years, the inhabitants of Lesnaya Grud' are already trying to decide what to do about it and how to possibly fix it.

In response to the cosmonauts' actions, the officials on Convention decide to prohibit them from ever returning to Earth. Moreover, they all vow never to mention what took place. In order to ensure their decision, the Americans and Soviets threaten to destroy any foreign spacecraft that comes into Earth's orbit, and both nations launch missile-equipped satellites to secure their threat. The aircraft carrier Convention is then handed over to neutral Finland, and the operation is shut down.

Characters

Burannyi Yedigei

Yedigei is the main protagonist. He is a railway worker on the Sarozek who was once a soldier in the second World War and before that, a fisherman on the Aral Sea. It is he who undertakes the responsibility for Kazangap's burial and most of the story is told from his perspective.

Kazangap

Kazangap was the oldest man in Buranly-Burranyi and originally encouraged Yedigei to move there. He worked alongside Yedigei on the railway. The "day" mentioned in the title The Day Lasts More than a Hundred Years is the day on which he is buried.

Ukubala

Ukubala is the wife of Yedigei. Overall, she is mostly submissive to his desires but does encourage him to seek an investigation into the death of Abutalip. Throughout the story, she is loyal to Yedigei and even overlooks his affection for Zaripa. On multiple occasions, Yedigei recalls them laboring together.

Main themes

Mankurt

Aitmatov draws in his book heavily on the tradition of the mankurts. According to Kyrgyz legend mankurts were prisoners of war who were turned into slaves by having their heads wrapped in camel skin. Under a hot sun these skins dried tight, like a steel band, thus enslaving them forever, which he likens this to a ring of rockets around the earth to keep out a higher civilisation. A mankurt did not recognise his name, family or tribe — "a mankurt did not recognise himself as a human being", he writes.[1]

N. Shneidman stated "The mankurt motif, taken from central Asian lore, is the dominant idea of the novel and connects the different narrative levels and time sequences".[2] In the later years of the Soviet Union Mankurt entered everyday speech to describe the alienation that people had toward a society that repressed them and distorted their history.[3] In former Soviet republics the term has come to represent those non Russians who have been cut off from their own ethnic roots by the effects of the Soviet system.[4]

Discussion is open about the origin of the word 'mankurt.' It was first used in the press by Aitmatov and he is said to have taken the word from Manas epos. 'Mankurt' may be derived from the Mongolian term "мангуурах" (manguurah, stupid), Turkic mengirt (one who was deprived memory) or (less probably) man kort (bad tribe) or even from Latin mens curtus (mind cut off).

Allusions/references to other works

Three folkstories are told within The Day Lasts More Than a Hundred Years:

- The story of Naiman-Ana, a woman killed by her mankurt son when she tries to free him.

- The story of Genghis Khan's white cloud got only created in 1989 as new chapter 9; it is not available in English; it is a story about a forbidden relationship between a Mongolian soldier, and a dragon banner maker.

- The story of Raimaly-aga, an aging bard who fell in love with a young woman but was tied to a tree by his family to prevent him from seeing her.

Film

In 1990 the film Mankurt (Манкурт) was released in the Soviet Union.[5] Written by Mariya Urmatova,[6] the film is based on one narrative strand from within the novel The Day Lasts More Than a Hundred Years.[7] It represents the last film directed by Khodzha Narliyev.[8] Its main cast was Tarik Tardzhan, Maya-Gozel Aymedova, Jylmaz Duru, Khodzhadurdy Narliev, Maysa Almazova. The film tells about a Turkmenian who defends his homeland from invasion. After he is captured, tortured, and brainwashed into serving his homeland's conquerors, he is so completely turned that he kills his mother when she attempts to rescue him from captivity.

References

- ↑ Excerpt from: celestial.com.kg

- ↑ Shneidman, N. N (1989). Soviet literature in the 1980s: decade of transition. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-5812-6.

- ↑ Horton, Andrew; Brashinsky, Michael (1992). The zero hour: glasnost and Soviet cinema in transition (illustrated ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 131. ISBN 0-691-01920-7.

- ↑ Laitin, David D. (1998). Identity in formation: the Russian-speaking populations in the near abroad (illustrated ed.). Cornell University Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-8014-8495-7.

- ↑ Oliver Leaman (2001). Companion encyclopedia of Middle Eastern and North African film. Taylor & Francis. p. 17. ISBN 9780415187039.

- ↑ Grzegorz Balski (1992). "Directory of Eastern European film-makers and films, 1945-1991". Flicks Books.

- ↑ Andrew Horton, Michael Brashinsky (1992). The zero hour: glasnost and Soviet cinema in transition. Princeton University Press. pp. 16, 17. ISBN 9780691019208.

- ↑ P. Rollberg (2009). Historical dictionary of Russian and Soviet cinema. Scarecrow Press. pp. 35, 37, 482. ISBN 9780810860728.