Digital humanities

Digital humanities (DH) is an area of scholarly activity at the intersection of computing and the disciplines of the humanities. The nature of this activity ranges broadly, from the practical, such as digitizing historical texts, to the philosophical, such as reflection on the nature of representation itself. This spectrum of activities is reflected in definitions of the field that range from it being a collection of methods to being a distinct epistemology and a kind of science. Within this variation, a distinctive feature of digital humanities is its cultivation of a two-way relationship between the humanities and the digital: the field both employs technology in the pursuit of humanities research and subjects technology to humanistic questioning and interrogation, often simultaneously.

Definition

The definition of the "digital humanities" is being continually formulated by scholars and practitioners; they ask questions and demonstrate through projects and collaborations with others. Collaboration is a major part of DH, with not only scholars sharing their research with other scholars, but with ongoing DH projects, the public can share their ideas about different topics with each other and learn from each other's opinion.

Historically, the digital humanities developed out of humanities computing, and has become associated with other fields, such as humanistic computing, social computing, and media studies. In concrete terms, the digital humanities embraces a variety of topics, from curating online collections of primary sources (primarily textual) to the data mining of large cultural data sets to the development of maker labs. Digital humanities incorporates both digitized (remediated) and born-digital materials and combines the methodologies from traditional humanities disciplines (such as history, philosophy, linguistics, literature, art, archaeology, music, and cultural studies) and social sciences,[2] with tools provided by computing (such as Hypertext, Hypermedia, data visualisation, information retrieval, data mining, statistics, text mining, digital mapping), and digital publishing. Related subfields of digital humanities have emerged like software studies, platform studies, and critical code studies. Fields that parallel the digital humanities include new media studies and information science as well as media theory of composition, game studies, particularly in areas related to digital humanities project design and production, cultural analytics and culturomics.[3][4]

In an interview on the subject of her work, Kathleen Fitzpatrick, an American scholar and exponent of the digital humanities, offers this practical definition: "For me it has to do with the work that gets done at the crossroads of digital media and traditional humanistic study. And that happens in two different ways. On the one hand, it’s bringing the tools and techniques of digital media to bear on traditional humanistic questions; on the other, it’s also bringing humanistic modes of inquiry to bear on digital media."[5] "A chapter in Debates in the Digital Humanities[6] offers twenty-one definitions culled from a far longer online list."[7]

Areas of inquiry

Digital humanities scholars use computational methods either to answer existing research questions or to challenge existing theoretical paradigms, generating new questions and pioneering new approaches. One goal is to systematically integrate computer technology into the activities of humanities scholars,[8] as is done in contemporary empirical social sciences. Such technology-based activities might include incorporation into the traditional arts and humanities disciplines use of text-analytic techniques; GIS; commons-based peer collaboration; and interactive games and multimedia.

Despite the significant trend in digital humanities towards networked and multimodal forms of knowledge, spanning social, visual, and haptic media, a substantial amount of digital humanities focuses on documents and text in ways that differentiate the field's work from digital research in Media studies, Information studies, Communication studies, and Sociology. Another goal of digital humanities is to create scholarship that transcends textual sources. This includes the integration of multimedia, metadata and dynamic environments. An example of this is The Valley of the Shadow project at the University of Virginia, the Vectors Journal of Culture and Technology in a Dynamic Vernacular at University of Southern California or Digital Pioneers projects at Harvard. Another issue in the digital humanities is the visualization of cultural data sets as researched by Curtin University in Perth, Australia.[9]

A growing number of researchers in digital humanities are using computational methods for the analysis of large cultural data sets such as the Google Books corpus.[3] Examples of such projects were highlighted by the Humanities High Performance Computing competition sponsored by the Office of Digital Humanities in 2008,[10] and also by the Digging Into Data challenge organized in 2009[11] and 2011[12] by NEH in collaboration with NSF,[13] and in partnership with JISC in the UK, and SSHRC in Canada.[14]

Environments and tools

Digital humanities takes place in an environment that might be as small as a mobile device or as large as a virtual reality lab. These are the environments for "creating, publishing and working with digital scholarship [and] include everything from personal equipment to institutes and software to cyberspace."[15]

It is also involved in the creation of software, providing "environments and tools for producing, curating, and interacting with knowledge that is 'born digital' and lives in various digital contexts."[16] In this context, the field is sometimes known as computational humanities. Many such projects share a "commitment to open standards and open source."[17]

History

Digital humanities descends from the field of humanities computing, of computationally enabled "formal representations of the human record,"[18] whose origins reach back to the late 1940s in the pioneering work of Roberto Busa.[19][20] In the decades which followed archaeologists, classicists, historians, literary scholars, and a broad array of humanities researchers in other disciplines applied emerging computational methods to transform humanities scholarship.[21]

Other aspects of digital humanities were descended from the IRIS Intermedia project on hypertext at Brown University in the 1980s.

The Text Encoding Initiative, born from the desire to create a standard encoding scheme for humanities electronic texts, is the outstanding achievement of early humanities computing. The project was launched in 1987 and published the first full version of the TEI Guidelines in May 1994.[20]

In the nineties, major digital text and image archives emerged at centers of humanities computing in the U.S. (e.g. the Women Writers Project,[22] the Rossetti Archive,[23] and The William Blake Archive[24]), which demonstrated the sophistication and robustness of text-encoding for literature.[25] The Blake archive, in particular, was designed by its editors to take advantage of "the syntheses made possible by the electronic medium" and thus accomplish an "editorial transformation" in the publication of Blake's work which was, from the author's hands, multimedia.[26]

The terminological change from "humanities computing" to "digital humanities" has been attributed to John Unsworth, Susan Schreibman, and Ray Siemens who, as editors of the anthology A Companion to Digital Humanities (2004), tried to prevent the field from being viewed as "mere digitization."[27] Consequently, the hybrid term has created an overlap between fields like rhetoric and composition, which use "the methods of contemporary humanities in studying digital objects,"[27] and digital humanities, which uses "digital technology in studying traditional humanities objects".[27] The use of computational systems and the study of computational media within the arts and humanities more generally has been termed the 'computational turn'.[28]

In 2006 the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), launched the Digital Humanities Initiative (renamed Office of Digital Humanities in 2008), which made widespread adoption of the term "digital humanities" all but irreversible in the United States.[29]

Digital humanities emerged from its former niche status and became "big news"[29] at the 2009 MLA convention in Philadelphia, where digital humanists made "some of the liveliest and most visible contributions"[30] and had their field hailed as "the first 'next big thing' in a long time."[31]

Today, many historical researches have used DH paradigms and tools for Knowledge Mobilization and Public Dissemination (see Boulou Ebanda de B'béri's [32] (The University of Ottawa) which uses the ArcGIS program to map out 19th century Black pioneer's settlement patterns in Southern Ontario.

Organizations and Institutions

The field of digital humanities is served by several organisations: The European Association for Digital Humanities (EADH), the Association for Computers and the Humanities (ACH), the Society for Digital Humanities/Société pour l'étude des médias interactifs (SDH/SEMI), the Japanese Association for Digital Humanities (JADH), the French-speaking Association for Digital Humanities (Humanistica) and the Australasian Association for Digital Humanities (aaDH), which are joined under the umbrella organisation of the Alliance of Digital Humanities Organizations (ADHO). The alliance funds a number of projects such as the Digital Humanities Quarterly, supports the Text Encoding Initiative, the organisation and sponsoring of workshops and conferences, as well as the funding of small projects, awards and bursaries.[33]

ADHO also oversees a joint annual conference, which began as the ACH/ALLC (or ALLC/ACH) conference, and is now known as the Digital Humanities conference.

CenterNet is an international network of about 100 digital humanities centers in 19 countries, working together to benefit digital humanities and related fields.[34][35]

Methods

The automatic analysis of vast textual corpora has created the possibility for scholars to analyze millions of documents in multiple languages with very limited manual intervention. Key enabling technologies have been Parsing, Machine Translation, Topic categorization, Machine Learning.

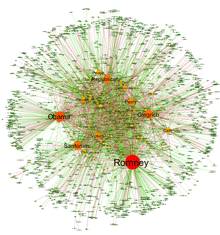

The automatic parsing of textual corpora has enabled the extraction of actors and their relational networks on a vast scale, turning textual data into network data. The resulting networks, which can contain thousands of nodes, are then analyzed by using tools from Network theory to identify the key actors, the key communities or parties, and general properties such as robustness or structural stability of the overall network, or centrality of certain nodes.[37] This automates the approach introduced by Quantitative Narrative Analysis,[38] whereby subject-verb-object triplets are identified with pairs of actors linked by an action, or pairs formed by actor-object.[36]

Content analysis has been a traditional part of social sciences and media studies for a long time. For example, in 2008, Yukihiko Yoshida did a study called[39] "Leni Riefenstahl and German expressionism: research in Visual Cultural Studies using the trans-disciplinary semantic spaces of specialized dictionaries." The study took databases of images tagged with connotative and denotative keywords (a search engine) and found Riefenstahl’s imagery had the same qualities as imagery tagged "degenerate" in the title of the exhibition, "Degenerate Art" in Germany at 1937.

The automation of content analysis has allowed a "big data" revolution to take place in that field, with studies in social media and newspaper content that include millions of news items. Gender bias, readability, content similarity, reader preferences, and even mood have been analyzed based on text mining methods over millions of documents [40] [41] [42] [43] and historical documents written in literary Chinese. [44] The analysis of readability, gender bias and topic bias was demonstrated in [45] showing how different topics have different gender biases and levels of readability; the possibility to detect mood shifts in a vast population by analyzing Twitter content was demonstrated as well.[46]

Criticism and controversies

Lauren F. Klein and Matthew K. Gold have identified a range of criticisms in the Digital Humanities field: 'a lack of attention to issues of race, class, gender, and sexuality; a preference for research-driven projects over pedagogical ones; an absence of political commitment; an inadequate level of diversity among its practitioners; an inability to address texts under copyright; and an institutional concentration in well-funded research universities'.[47] This article mentions many appearances of the Digital Humanities in public media, often in a critical fashion. Digital Humanities has been hailed as a solution to the apparent problems within the humanities, namely a decline in funding, a repeat of debates, and a moribund set of theoretical claims and methodological arguments.[48]

Armand Leroi, writing in the New York Times, discusses the contrast between the algorithmic analysis of themes in literary texts and the work of Harold Bloom, who qualitatively and phenomenologically analyzes the themes of literature over time and through history. The central point of contention is whether or not the Digital Humanities can provide a truly robust analysis of literature and social phenomenon. Can the Digital Humanities provide a novel alternative perspective on the questions asked within the Humanities and Social Sciences?

It has been criticized for not only not paying attention to the traditional questions of lineage and history in the Humanities, but lacking the fundamental cultural criticism that defines the Humanities. However, it remains to be seen whether or not the Humanities have to be tied to cultural criticism, per se, in order to be the Humanities.[49] Alternatively, perhaps this does not matter, as the Digital Humanities could be fundamentally a different enterprise than the Humanities, not a replacement or even supplement.

Adam Kirsch, writing in the New Republic, calls this the "False Promise" of the Digital Humanities.[50] While the rest of Humanities and many Social Science departments are seeing a decline in funding or prestige, the Digital Humanities have been seeing increasing funding and prestige. Burdened with the problems of novelty, the Digital Humanities are discussed as either a revolutionary alternative to the Humanities as we know it or as simply new wine in old bottles. Kirsch attests that the Digital Humanities as currently constructed suffers from problems of being marketers rather than scholars, who attest to the grand capacity of their research more than actually performing new analysis and when they do so, only performing trivial parlor tricks of research. This form of criticism has been repeated by others, such as in Carl Staumshein, writing in Inside Higher Education, who calls it a "Digital Humanities Bubble" [51] and later, in the same publication, Straumshein alleges that the Digital Humanities are a 'Corporatist Restructuring' of the Humanities.[52] Some see the alliance of the Digital Humanities with business to be positive and as they are something to which the business world can pay attention, thus bringing funding and attention to the humanities that it needs.[53] If it were not burdened by the title of Digital Humanities it could escape the allegations that it is elitist and unfairly funded.[54] Furthermore, researchers in the sciences see the Digital Humanities as a welcome improvement over the non-quantitative and repetitive historically popular methods of the humanities and social sciences.[55][56]

Johanna Drucker, a professor at UCLA in the Department of Information Studies, has also criticized the "epistemological fallacies" prevalent in popular visualization tools and technologies (such as Google's n-gram graph) used by digital humanities scholars and the general public, calling some network diagramming and topic modeling tools "just too crude for humanistic work." [57] The lack of transparency in these programs obscure the subjective nature of the data and its processing, she argues, as these programs "generate standard diagrams based on conventional algorithms for screen display...mak[ing] it very difficult for the semantics of the data processing to be made evident." [57]

The literary theorist Stanley Fish claims that the digital humanities pursue a revolutionary agenda and thereby undermine the conventional standards of "pre-eminence, authority and disciplinary power."[58]

There has also been some recent controversy amongst practitioners of digital humanities around the role that race and/or identity politics plays in digital humanities. Tara McPherson attributes some of the lack of racial diversity in digital humanities to the modality of UNIX and computers, themselves.[59] An open thread on DHpoco.org recently garnered well over 100 comments on the issue of race in digital humanities, with scholars arguing about the amount that racial (and other) biases affect the tools and texts available for digital humanities research.[60] McPherson posits that there needs to be an understanding and theorizing of the implications of digital technology and race, even when the subject for analysis appears not to be about race.

Amy E. Earheart criticizes what has become the new digital humanities "canon" in the shift from websites using simple HTML to the usage of the TEI and visuals in textual recovery projects.[61] Works that has been previously lost or excluded were afforded a new home on the internet, but much of the same marginalizing practices found in traditional humanities also took place digitally. According to Earhart, there is a "need to examine the canon that we, as digital humanists, are constructing, a canon that skews toward traditional texts and excludes crucial work by women, people of color, and the GLBTQ community."[61]

Practitioners in digital humanities are also failing to meet the needs of users with disabilities. George H. Williams argues that universal design is imperative for practitioners to increase usability because "many of the otherwise most valuable digital resources are useless for people who are—for example—deaf or hard of hearing, as well as for people who are blind, have low vision, or have difficulty distinguishing particular colors." [62] In order to provide accessibility successfully, and productive universal design, it is important to understand why and how users with disabilities are using the digital resources while remembering that all users approach their informational needs differently.[62]

See also

Centers

- Department of Digital Humanities (King's College London, UK)

- Humanities Advanced Technology and Information Institute (University of Glasgow, Scotland)

- Sussex Humanities Lab (University of Sussex, UK)

- Center for Digital Research in the Humanities (University of Nebraska-Lincoln, USA)

- Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities (University of Virginia, USA)

- Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities

- Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media (George Mason University, Virginia, USA)

- UCL Centre for Digital Humanities (University College London, UK)

- Center for Public History and Digital Humanities (Cleveland State University)

- Scholars' Lab (University of Virginia)

- Centre for Digital Humanities Research (Australian National University)

Meetings

- Digital Humanities conference

- HASTAC

- THATCamp

- DHSI, University of Victoria, Canada

- The European Summer University in Digital Humanities, Leipzig University, Germany

Resources

Miscellaneous

- Computers and writing

- Computational archaeology

- Cybertext

- Cultural analytics

- Digital Classicist

- Digital Humanities Summer Institute

- Digital library

- Digital Medievalist

- Digital history

- Digitizing

- Digital rhetoric

- Digital scholarship

- Electronic Cultural Atlas Initiative

- Electronic literature

- EpiDoc

- E-research

- Humanistic informatics

- Multimedia literacy

- New media

- Systems theory

- Stylometry

- Text Encoding Initiative

- Text mining

- Topic Modeling

- Transliteracy

References

- ↑ League of Nations archives, United Nations Office in Geneva. Network visualization and analysis published in Grandjean, Martin (2014). "La connaissance est un réseau". Les Cahiers du Numérique. 10 (3): 37–54. doi:10.3166/lcn.10.3.37-54. Retrieved 2014-10-15.

- ↑ "Digital Humanities Network". University of Cambridge. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- 1 2 Roth, S. (2014), "Fashionable functions. A Google n-gram view of trends in functional differentiation (1800-2000)", International Journal of Technology and Human Interaction, Band 10, Nr. 2, S. 34-58 (online: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2491422).

- ↑ Liu, C.-L., G. Jin, Q. Liu, W.-Y. Chiu, and Y.-S. Yu. (2011) "Some chances and challenges in applying language technologies to historical studies in Chinese", International Journal of Computational Linguistics and Chinese Language Processing, 16(1-2):27‒46. (http://arxiv.org/abs/1210.5898)

- ↑ "On Scholarly Communication and the Digital Humanities: An Interview with Kathleen Fitzpatrick", In the Library with the Lead Pipe

- ↑ "Day of DH: Defining the Digital Humanities," in Debates in the Digital Humanities, ed. Matthew K. Gold (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012), 69–71.

- ↑ Gardiner, Eileen and Ronald G. Musto. (2015). The Digital Humanities: A Primer for Students and Scholars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 5.

- ↑ Opportunities/tabid/57/Default.aspx "Grant Opportunities" Check

|url=value (help). National Endowment for the Humanities, Office of Digital Humanities Grant Opportunities. Retrieved 25 January 2012. - ↑ "Curtin University, Visualisation Technologies, Perth, Australia".

- ↑ Bobley, Brett (December 1, 2008). "Grant Announcement for Humanities High Performance Computing Program". National Endowment for the Humanities. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- ↑ "Awardees of 2009 Digging into Data Challenge". Digging into Data. 2009. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- ↑ "NEH Announces Winners of 2011 Digging Into Data Challenge". National Endowment for the Humanities. January 3, 2012. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- ↑ Cohen, Patricia (2010-11-16). "Humanities Scholars Embrace Digital Technology". The New York Times. New York. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- ↑ Williford, Christa; Henry, Charles (June 2012). "Computationally Intensive Research in the Humanities and Social Sciences: A Report on the Experiences of First Respondents to the Digging Into Data Challenge". Council on Library and Information Resources. ISBN 978-1-932326-40-6.

- ↑ Gardiner, Eileen and Ronald G. Musto. (2015). The Digital Humanities: A Primer for Students and Scholars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 83.

- ↑ Presner, Todd (2010). "Digital Humanities 2.0: A Report on Knowledge". Connexions. Retrieved 2012-06-09.

- ↑ Bradley, John (2012). "No job for techies: Technical contributions to research in digital humanities". In Marilyn Deegan and Willard McCarty (eds.). Collaborative Research in the Digital Humanities. Farnham and Burlington: Ashgate. pp. 11–26 [14]. ISBN 9781409410683.

- ↑ Unsworth, John (2002-11-08). "What is Humanities Computing and What is not?". Jahrbuch für Computerphilologie. 4. Retrieved 2012-05-31.

- ↑ Svensson, Patrik (2009). "Humanities Computing as Digital Humanities". Digital Humanities Quarterly. 3 (3). ISSN 1938-4122. Retrieved 2012-05-30.

- 1 2 Hockney, Susan (2004). "The History of Humanities Computing". In Susan Schreibman, Ray Siemens, John Unsworth (eds.). Companion to Digital Humanities. Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 1405103213.

- ↑ Feeney, Mary & Ross, Seamus (1994). "Information Technology in Humanities Scholarship, British Achievements, Prospects, and Barriers". Historical Social Research. 19 (1 (69)): 3–59. JSTOR 20755828.

- ↑ Women Writers Project, Brown University, retrieved 2012-06-16

- ↑ Jerome J. McGann (ed.), Rossetti Archive, Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities, University of Virginia, retrieved 2012-06-16

- ↑ Morris Eaves, Robert Essick, and Joseph Viscomi (eds.), The William Blake Archive, retrieved 2012-06-16

- ↑ Liu, Alan (2004). "Transcendental Data: Toward a Cultural History and Aesthetics of the New Encoded Discourse". Critical Inquiry. 31 (1): 49–84. doi:10.1086/427302. ISSN 0093-1896. JSTOR 10.1086/427302.

- ↑ "Editorial Principles". The William Blake Archive. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 Fitzpatrick, Kathleen (2011-05-08). "The humanities, done digitally". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved 2011-07-10.

- ↑ Berry, David (2011-06-01). "The Computational Turn: Thinking About the Digital Humanities". Culture Machine. Retrieved 2012-01-31.

- 1 2 Kirschenbaum, Matthew G. (2010). "What is Digital Humanities and What's it Doing in English Departments?" (PDF). ADE Bulletin (150).

- ↑ Howard, Jennifer (2009-12-31). "The MLA Convention in Translation". The Chronicle of Higher Education. ISSN 0009-5982. Retrieved 2012-05-31.

- ↑ Pannapacker, William (2009-12-28). "The MLA and the Digital Humanities" (The Chronicle of Higher Education). Brainstorm. Retrieved 2012-05-30.

- ↑ The Promised Land Project

- ↑ Vanhoutte, Edward (2011-04-01). "Editorial". Literary and Linguistic Computing. 26 (1): 3–4. doi:10.1093/llc/fqr002. Retrieved 2011-07-11.

- ↑ "About". CenterNet. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ↑ Caraco, Benjamin (1 January 2012). "Les digital humanities et les bibliothèques". Le Bulletin des Bibliothèques de France. 57 (2). Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- 1 2 Automated analysis of the US presidential elections using Big Data and network analysis; S Sudhahar, GA Veltri, N Cristianini; Big Data & Society 2 (1), 1-28, 2015

- ↑ Network analysis of narrative content in large corpora; S Sudhahar, G De Fazio, R Franzosi, N Cristianini; Natural Language Engineering, 1-32, 2013

- ↑ Quantitative Narrative Analysis; Roberto Franzosi; Emory University © 2010

- ↑ Yoshida,Yukihiko, Leni Riefenstahl and German Expressionism: A Study of Visual Cultural Studies Using Transdisciplinary Semantic Space of Specialized Dictionaries, Technoetic Arts: a journal of speculative research (Editor Roy Ascott),Volume 8, Issue3, intellect , 2008

- ↑ Flaounas, I.; Turchi, M.; Ali, O.; Fyson, N.; Bie, T. De; Mosdell, N.; Lewis, J.; Cristianini, N. (2010). "The Structure of EU Mediasphere". PLoS ONE. 5 (12): e14243. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014243.

- ↑ Lampos, V; Cristianini, N. "Nowcasting Events from the Social Web with Statistical Learning". ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology (TIST). 3 (4): 72. doi:10.1145/2337542.2337557.

- ↑ NOAM: news outlets analysis and monitoring system; I Flaounas, O Ali, M Turchi, T Snowsill, F Nicart, T De Bie, N Cristianini Proc. of the 2011 ACM SIGMOD international conference on Management of data

- ↑ Automatic discovery of patterns in media content, N Cristianini, Combinatorial Pattern Matching, 2-13, 2011

- ↑ Bol, P. K., C.-L. Liu, and H. Wang. (2015) "Mining and discovering biographical information in Difangzhi with a language-model-based approach", Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Digital Humanities. (http://arxiv.org/abs/1504.02148)

- ↑ I. Flaounas, O. Ali, T. Lansdall-Welfare, T. De Bie, N. Mosdell, J. Lewis, N. Cristianini, RESEARCH METHODS IN THE AGE OF DIGITAL JOURNALISM, Digital Journalism, Routledge, 2012

- ↑ Effects of the Recession on Public Mood in the UK; T Lansdall-Welfare, V Lampos, N Cristianini; Mining Social Network Dynamics (MSND) session on Social Media Applications

- ↑ "Debates in the Digital Humanities".

- ↑ Leroi, Armand. "Digitizing the Humanities". The New York Times Online. The New York Times. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ↑ Liu, Alan. "Where is Cultural Criticism in the Digital Humanities?". UCSB. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ↑ Kirsch, Adam. "Technology Is Taking Over English Departments". The New Republic. The New Republic. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ↑ Straumshein, Carl. "Digital Humanities Bubble". Inside Higher Education. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ↑ Straumshein, Carl. "Digital Humanities as 'Corporatist Restructuring'". Inside Higher Education. Inside Higher Education. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ↑ Carlson, Tracy. "Humanities and business go hand in hand". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ↑ Pannapacker, William. "Stop Calling It 'Digital Humanities'". Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ↑ "'Poetry in Motion'". Nature. Nature. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ↑ Kirschenbaum, Matthew. "What Is "Digital Humanities," and Why Are They Saying Such Terrible Things about It?" (PDF). Wordpress. Matthew Kirschenbaum. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- 1 2 "Johanna Drucker (UCLA) Lecture, "Should Humanists Visualize Knowledge?"". Vimeo. Retrieved 2016-01-25.

- ↑ Fish, Stanley (2012-01-09). "The Digital Humanities and the Transcending of Mortality". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved 2012-05-30.

- ↑ "Debates in the Digital Humanities".

- ↑ "Open Thread: The Digital Humanities as a Historical "Refuge" from Race/Class/Gender/Sexuality/Disability?".

- 1 2 http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/16

- 1 2 http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/44

Bibliography

- Beagle, Donald, (2014). Digital Humanities in the Research Commons: Precedents & Prospects, Association of College & Research Libraries: dh+lib.

- Benzon, William, & David G. Hays (1976). "Computational Linguistics and the Humanist". Computers and the Humanities, vol. 10, pp. 265–274.

- Berry, D. M., ed. (2012). Understanding Digital Humanities, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Burdick, Anne, Johanna Drucker, Peter Lunenfeld, Todd Presner, & Jeffrey Schnap (2012). Digital_Humanities, The MIT Press

- Busa, Roberto (1980). ‘The Annals of Humanities Computing: The Index Thomisticus’, in Computers and the Humanities vol. 14, pp. 83–90. Computers and the Humanities (1966-2004)

- Celentano, A., Cortesi, A. & Mastandrea, P. (2004). Informatica Umanistica: una disciplina di confine, Mondo Digitale, vol. 4, pp. 44–55.

- Classen, Christoph, Kinnebrock, Susanne, & Löblich, Maria, eds. (2012). Towards Web History: Sources, Methods, and Challenges in the Digital Age. Historical Social Research, 37 (4), 97-188.

- Condron Frances, Fraser, Michael & Sutherland, Stuart, eds. (2001). Oxford University Computing Services Guide to Digital Resources for the Humanities, West Virginia University Press.

- Fitzpatrick, Kathleen (2011). Planned Obsolescence: Publishing, Technology, and the Future of the Academy. New York; NYU Press. ISBN 9780814727874

- Gardiner, Eileen and Ronald G. Musto. (2015). The Digital Humanities: A Primer for Students and Scholars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gold, Matthew K., ed. (2012). Debates In the Digital Humanities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Grandjean, Martin (2016). "A social network analysis of Twitter: Mapping the digital humanities community". Cogent Arts & Humanities. 3 (1): 1171458. doi:10.1080/23311983.2016.1171458.

- Hancock, B.; Giarlo, M.J. (2001). "Moving to XML: Latin texts XML conversion project at the Center for Electronic Texts in the Humanities". Library Hi Tech. 19 (3): 257–264. doi:10.1108/07378830110405139.

- Heftberger, Adelheid (2016). Kollision der Kader. Dziga Vertovs Filme, die Visualisierung ihrer Strukturen und die Digital Humanities. Munich: edition text + kritik.

- Hockey, Susan (2001). Electronic Text in the Humanities: Principles and Practice, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Honing, Henkjan (2008). "The role of ICT in music research: A bridge too far?". International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing. 1 (1): 67–75.

- Inman James, Reed, Cheryl, & Sands, Peter, eds. (2003). Electronic Collaboration in the Humanities: Issues and Options, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Kenna, Stephanie & Ross, Seamus, eds. (1995). Networking in the humanities: Proceedings of the Second Conference on Scholarship and Technology in the Humanities held at Elvetham Hall, Hampshire, UK 13–16 April 1994. London: Bowker-Saur.

- Kirschenbaum, Matthew (2008). Mechanisms: New Media and the Forensic Imagination. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

- Manovich, Lev (2013). 'Software Takes Command. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

- McCarty, Willard (2005). Humanities Computing, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Moretti, Franco (2007). Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for Literary History. New York: Verso.

- Mullings, Christine, Kenna, Stephanie, Deegan, Marilyn, & Ross, Seamus, eds. (1996). New Technologies for the Humanities London: Bowker-Saur.

- Newell, William H., ed. (1998). Interdisciplinarity: Essays from the Literature. New York: College Entrance Examination Board.

- Nowviskie, Bethany, ed. (2011). Alt-Academy: Alternative Academic Careers for Humanities Scholars. New York: MediaCommons.

- Ramsay, Steve (2011). Reading Machines: Toward an Algorithmic Criticism. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Schreibman, Susan, Siemens, Ray & Unsworth, John, eds. (2004). A Companion To Digital Humanities Blackwell Publishers.

- Selfridge-Field, Eleanor, ed. (1997). Beyond MIDI: The Handbook of Musical Codes. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Thaller, Manfred (2012). "Controversies around the Digital Humanities". Historical Social Research. 37 (3): 7–229.

- Tötösy de Zepetnek, Steven (2013). Digital Humanities and the Study of Intermediality in Comparative Cultural Studies. Ed. Steven Tötösy de Zepetnek. West Lafayette: Purdue Scholarly Publishing Services.

- Unsworth, John (2005). Scholarly Primitives: What methods do humanities researchers have in common, and how might our tools reflect this?

- Warwick C., Terras, M., & Nyhan, J., eds. (2012). Digital Humanities in Practice, Facet Publishing

- YOSHIDA,Yukihiko,"Leni Riefenstahl and German Expressionism: A Study of Visual Cultural Studies Using Transdisciplinary Semantic Space of Specialized Dictionaries",Technoetic Arts: a journal of speculative research (Editor Roy Ascott),Volume 8, Issue3,intellect,2008

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Digital humanities. |

- What is digital humanities? - a critical project highlighting the diversity of DH definitions

- The Alliance of Digital Humanities Organizations - the main international alliance of DH programs

- CenterNet - Mapping of DH centers