The History and Present State of Electricity

The History and Present State of Electricity (1767), by eighteenth-century British polymath Joseph Priestley, is a survey of the study of electricity up until 1766 as well as a description of experiments by Priestley himself.[1]

Background

Priestley became interested in electricity while he was teaching at Warrington Academy. Friends introduced him to the major British experimenters in the field: John Canton, William Watson, and Benjamin Franklin. These men encouraged Priestley to perform the experiments he was writing about in his history; they believed that he could better describe the experiments if he had performed them himself. In the process of replicating others' experiments, however, Priestley became intrigued by the still unanswered questions regarding electricity and was prompted to design and undertake his own experiments.[2]

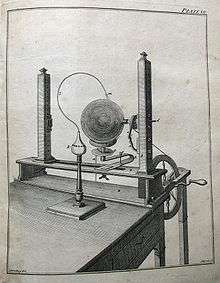

Priestley possessed an electrical machine designed by Edward Nairne. With his brother Timothy he designed and constructed his own machines (see Timothy Priestley#Scientific apparatus).[3]

Contents

The first half of the 700-page book is a history of the study of electricity. It is parted into ten periods, starting with early experiments "prior to those of Mr. Hawkesbee", finishing with variable experiments and discoveries made after Franklin's own experiments. The book takes Franklin's work into focus, which was criticised by contemporary scholars, especially in France and Germany.[4] The second and more influential half contents a description of contemporary theories about electricity and suggestions for future research. Priestley also wrote about the construction and use of electrical machines, basic electrical experiments and "practical maxims for the usw of young elecricians". In the second edition, Priestley added some of his own discoveries, such as the conductivity of charcoal.[5] This discovery overturned what he termed "one of the earliest and universally received maxims of electricity," that only water and metals could conduct electricity. Such experiments demonstrate that Priestley was interested in the relationship between chemistry and electricity from the beginning of his scientific career.[6] In one of his more speculative moments, he "provided a mathematical quasi-demonstration of the inverse-square force law for electrical charges. It was the first respectable claim for that law, out of which came the development of a mathematical theory of static electricity."[7]

The book contains an account of the kite experiment of Benjamin Franklin, that has been taken as authoritative. Some details not found elsewhere are presumed to have been communicated by Franklin.[8] The status of this account matters for the priority dispute over the experiment in which Franklin became involved.[9] The focus on Franklin's experiments influenced the reception of his work in Europe. Pristley's famous text supported the distribution of Franklin's research, which helped it becoming one of the most important works on electricity in the late 18th century.[10]

Influence

Priestley's strength as a natural philosopher was qualitative rather than quantitative and his observation of "a current of real air" between two electrified points would later interest Michael Faraday and James Clerk Maxwell as they investigated electromagnetism. Priestley's text became the standard history of electricity for over a century; Alessandro Volta (who would go on to invent the battery), William Herschel (who discovered infrared radiation), and Henry Cavendish (who discovered hydrogen) all relied upon it. Priestley wrote a popular version of the History of Electricity for the general public titled A Familiar Introduction to the Study of Electricity (1768).[11]

Notes

- ↑ Priestley, Joseph. The History and Present State of Electricity, with original experiments. London: Printed for J. Dodsley, J. Johnson and T. Cadell, 1767.

- ↑ Schofield, 141–44; 152; Jackson, 64–66; Uglow 75–77; Thorpe, 61–65.

- ↑ W. D. A. Smith, Under the Influence: A history of nitrous oxide and oxygen anaesthesia, Macmillan (1982), pp. 5–7.

- ↑ Heilbron, J. L. "Franklin, Haller, and Franklinist History." Isis 68, no. 4 (1977): 539-49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/230008. p. 545.

- ↑ Schofield, 144ff.

- ↑ Gibbs 28–31; see also Thorpe, 64.

- ↑ Schofield, 150.

- ↑ Michael Brian Schiffer; Kacy L. Hollenback; Carrie L. Bell (1 October 2003). Draw the Lighting Down: Benjamin Franklin and Electrical Technology in the Age of Enlightenment. University of California Press. p. 310 note 23. ISBN 978-0-520-23802-2. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- ↑ Professor I Bernard Cohen, PH.D PH.D (1990). Benjamin Franklin's Science. Harvard University Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-674-06659-5. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- ↑ Heilbron, J. L. "Franklin, Haller, and Franklinist History." Isis 68, no. 4 (1977): 539-49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/230008. p. 545-546.

- ↑ Priestley, Joseph. A familiar introduction to the study of electricity. London: Printed for J. Dodsley; T. Cadell; and J. Johnson, 1768.

Bibliography

- Gibbs, F. W. Joseph Priestley: Adventurer in Science and Champion of Truth. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1965.

- Jackson, Joe, A World on Fire: A Heretic, An Aristocrat And The Race to Discover Oxygen. New York: Viking, 2005. ISBN 0-670-03434-7.

- Schofield, Robert E. The Enlightenment of Joseph Priestley: A Study of his Life and Work from 1733 to 1773. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-271-01662-0.

- Thorpe, T.E. Joseph Priestley. London: J. M. Dent, 1906.

- Uglow, Jenny. The Lunar Men: Five Friends Whose Curiosity Changed the World. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002. ISBN 0-374-19440-8.

External links

- Priestley, Joseph. The History and Present State of Electricity, with original experiments. London: Printed for J. Dodsley, J. Johnson and T. Cadell, 1767. (Third edition, 1775)