The West as America Art Exhibition

The West as America, Reinterpreting Images of the Frontier, 1820–1920, an art exhibition organized by the Smithsonian American Art Museum (then known as the National Museum of American Art, or NMAA) in 1991, caused an unforeseen controversy and according to art critics, "engaged the public in the debate over western revisionism on an unprecedented scale."[1]

The paintings at the Smithsonian American Art Museum represent the United States' government’s oldest art collection and in its 160-year history the museum had not received much detrimental publicity before this exhibition.[2]

The goal of the curators of The West as America was to reveal how artists during this period visually revised the conquest of the West in an effort to correspond with a national ideology that favored Western expansionism. By mixing New West historiographical interpretation with Old West art, the curators sought not only to show how these frontier images have defined our idea of the national past but also to dispel the traditional beliefs behind the images.[3] Many who visited the exhibit missed the curator’s point and instead became incensed with what they saw as the curator’s dismantling of the history and legacy of the American western frontier.[4]

Republican members of the Senate Appropriations Committee were angered by what they termed the show’s "political agenda" and threatened to cut funds to the Smithsonian Institution.[5]

Controversial reviews generated widespread media coverage, both negative and positive, in leading newspapers, magazines, and art journals. Television crews from Austria, Italy and the United States Information Agency vied to videotape the show before its 164 paintings, drawings, photographs, sculptures and prints, along with the 55 text panels accompanying the artworks were taken down.[2]

Several key factors, including a prominent venue, skillful promotion, widespread publicity, elaborate catalog and the importance of the artworks themselves all contributed to the impact of the exhibition. Timing also played a part in fostering public response both pro and con as the show’s run coincided with events such as the collapse of the Soviet Union, the allied victory in the Gulf War, the resurgence of multiculturalism and the revival of public interest in western themes in fashion, advertising, music, literature and film.[1]

Controversy

The history of the expansion to the west is viewed by some as a vital component in explaining the structure of the United States’ national identity. There are competing visions of the western past that assume different western significances and these newer versions of western history were being emphasized at the show. The NMAA director, Elizabeth Broun stated, “The museum took a major step toward redefining western history, western art and national culture.”[6]

The conclusions set forth in the The West as America were rooted in revisionist studies such as Henry Nash Smith’s Virgin Land: The American West as Symbol and Myth, Richard Slotkin’s Regeneration Through Violence: The Mythology of the American Frontier, 1600–1860 (1973) and William H. and William N. Goetzmann’s book and 1986 PBS television series, The West of the Imagination.[1]

A writer for the The Journal of American History, Andrew Gulliford, stated in his article entitled "The West as America: Reinterpreting Images of the Frontier, 1820–1920 "The West as America gave no praise or tribute to the grandeur and majesty of the western landscape or to the nation-building ethos of the pioneering experience. Instead, exhibition labels presented the truth of conquest and exploitation in US history, an approach that struck many visitors and reviewers as heretical."[2]

Other exhibitions and programs that focused on western history include, “The American Frontier: Images & Myths” at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1973; “Frontier America: The Far West” at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston in 1975; “Treasures of the Old West” at the Thomas Gilcrease Institute in 1984; “American Frontier Life” at the Amon Carter Museum of Western Art in 1987; and, “Frontier America” at the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in 1988.”[2]

_by_Joshua_Shaw.jpg)

According to The Western Historical Quarterly writer, B. Byron Price, the traditions and myths at the core of western art, in addition to the expense of exhibit installations and practical constraints such as time, space, format, patronage, and availability of collections contribute to the resistance of museums to attempt shows of historical revision and why conventional monolithic view of the West as a romantic and triumphant adventure remain the mode in many art exhibits today.[1]

Revisionist themes appear more often in the story lines of high-profile temporary and traveling shows like The American Cowboy, organized by the Library of Congress in 1983, The Myth of the West, a 1990 show offering from the Henry Gallery of the University of Washington, and Discovered Lands, Invented Pasts, a cooperative effort of the Gilcrease Museum, the Yale University Art Gallery, and the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library in 1992.[1]

These shows did not generate the level of controversy seen at the NMAA's The West As America exhibit. According to art reviews, what set apart past shows on the west and The West as America was the show’s “strident rhetoric”.[1] Andrew Gulliford writes, "Few Americans were prepared for the blunt and incisive exhibit labels, which sought to reshape the opinions of museum visitors and to jar them out of their traditional assumptions about western art as authentic."[2] According to B. Byron Price, "Several people appreciated the serious, critical attention accorded to artwork and found merit in the complexity of analysis and the curator's interpretation of western art."[1]

The exhibition

The West as America exhibition included 164 works of art by 86 well-known artists and was curated by William H. Truettner and a team of seven scholars of American art including Nancy K. Anderson, Patricia Hills, Elizabeth Johns, Joni Louise Kinsey, Howard R. Lamar Alex Nemerov and Julie Schimmel.[3]

A text panel in the last section of the show reads,

"The art of Frederic Remington, Charles Schreyvogel, Charles Russell, Henry Farny, and other turn-of-the-century artists has been called a “permanent record” of nineteenth century frontier America. Yet, as the accompanying photographs of Schreyvogel attests, these artist often created their work in circumstances vastly removed from frontier America itself.”[7]

Artist Frederic Remington’s painting Fight for the Water Hole (1903), which was displayed in the last section of the show's thematic exhibit, was accompanied by a wall text with a quote from the artist that read,

“I sometimes feel that I am trying to do the impossible with my pictures in not having a chance to work direct but as there are no people such as I paint it’s “studio” or nothing.”[7]

Truettner’s intention was not to criticize western art but to acknowledge the way the art of the West imaginatively invented its subjects. Truettner sought to demonstrate the deep ties between the art and the artists’ participation in the American Art-Union during the antebellum period and to show that many artists' works were influenced by patronage from capitalist and industrialists of the Gilded Age.[2]

Another wall text read,

“Although they reveal isolated facts about the West, the paintings in this section reveal far more about the urban, industrial culture in which they were made and sold. For it was according to this culture’s attitudes – attitudes about race, class, and history – that artists such as Schreyvogel and Remington created that place we know as the “Old West.""[7]

The NMAA produced a 390-page book for the exhibit, which was edited by Truettner and included a forward by the NMAA director, Elizabeth Broun. In addition, the NMAA produced a handbook entitled “A Guide for Teachers,” intended for grades 10 -12 to help students develop the ability to interpret works of art and to see how and why works of art create meaning. The handbook states, “…. the exhibition at the NMAA argues that this art is not an objective account of history and that art is not necessarily history; seeing is not necessarily believing.”[8]

Through the use of the 55 written text labels, the exhibition curator explicitly asked the audience to “see through” the images to the historical conditions that produced them. This technique raised what critics called "uncomfortable questions about basic American myths and their relationship to art."

Roger B. Stein, in an article for The Public Historian entitled, "Visualizing Conflict in 'The West As America,'" took the view that the show effectively communicated its revisionist claims by insisting upon a nonliteral way of reading images through its use of textblocks. He writes, "Visually the exhibition made its subject not just "images of the West," but the process of seeing and the process of making images – the images are social and aesthetic constructions, choices we make about a subject matter."[9] Other critics accused the NMAA curator of "redefining western artists as apologists for Manifest Destiny who were culturally blind to the displacement of indigenous people and ignored the environmental degradation that accompanied the settling of the West."[2]

Both the curator and the director stated they presented an exhibition on American art that described how images have been misconstrued as truthful representations of history, "But," director Broun stated, “the public changed the terms of the debate.” Truettner added, “We thought we were doing a show on images in history, but the public was more concerned that we had challenged a sacred premise.”[2]

Thematic layout of the exhibition

The exhibition consisted of 164 works (more than 300 illustrations in the book) created by 86 artists during 1820–1920.

In an effort to create a show that would effectively question past interpretations of familiar works by these artists, the curator divided the artworks into six thematic categories that were accompanied by 55 written text labels. The text labels commented on the artwork and introduced popular and/or dissenting material.

“Prelude to Expansion: Repainting the Past”

The exhibition began with historical paintings that introduced the concept of national expansion and included representations of colonial and pre-colonial events such as white male Europeans encountering an unknown continent.

One of the first text labels read,

“The paintings in this gallery and those that follow should not be seen as a record of time and place. More often than not they are contrived views, meant to answer the hopes and desires of people facing a seemingly unlimited and mostly unsettled portion of the nation.”[10]

Truettner writes "...images from Christopher Columbus to Kit Carson show the discovery and settlement of the West as a heroic undertaking. Many nineteenth-century artists and the public believed that these images represented a faithful account of civilization moving westward. A more recent approach argues that these images are carefully staged fiction and that heir role was to justify the hardship and conflict of nation building. Western scenes extolled progress but rarely noted damaging social and environmental change."[3]

Another text label read,

"This exhibition assumes that all history is unconsciously edited by those who make it. Looking beneath the surface of these images gives us a better understanding of why national problems created during the era of western expansion still affect us today.”[7]

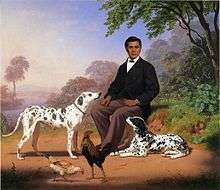

Works in this section included Emanuel Leutze’s Christopher Columbus on Santa Maria in 1492 (1855), which shows Christopher Columbus gesturing toward the New World, Peter F. Rothermel’s Columbus before the Queen (1852) and Landing of the Pilgrims (1854), Thomas Moran’s Ponce de León in Florida, 1514 (1878), Emanuel Leutze’s The Storming of the Teocali by Cortez and His Troops (1848), Joshua Shaw’s The Coming of the White Man (1850), and Robert W. Weir’s Embarkation of the Pilgrims at Delft Haven, Holland, July 22, 1620, (1857). Colonial painting include Robert W. Weir’s The Landing of Henry Hudson (1838) and Emanuel Leutze’s Founding of Maryland (1860).

“Picturing Progress in the Era of Western Expansion”

The second section of the exhibition focused on portraits of prominent settlers and images of scouts, pioneers and European immigrants moving west across an unpopulated landscape.

William S. Jewett’s The Promised Land – The Grayson Family (1850), portrays a prosperous-looking man with his wife and son, all gazing west, posed against a golden landscape. The text labels called it, “more rhetorical than factual,” an image that “ignores the controversy that attended national expansion by equating the westward trek of the Grayson Family with white people’s belief in the idea of progress.”[10]

John Gast’s American Progress (1872) shows “Manifest Destiny”, the religious belief, popular in the 1840s and 1850s, that the United States was impelled by providence to expand its territory.[11]

Called the “Spirit of the Frontier” it was widely distributed as an engraving that portrayed settlers moving west, guided and protected by a goddess-like figure of Columbia aided by technology (railways, telegraphs) and driving Native Americans and bison into obscurity. The painting shows the angel-like figure bringing along light seen on the eastern side of the painting as she travels towards the darkened west.

Albert Bierstadt’s Emigrants Crossing the Plains, 1867, portrays a picturesque party of Germans going to Oregon. The canvas shows the warmth of the setting sun and spectacular hues streaking across the sky, which illuminate the sheer cliffs to the right. According to Truettner, paintings constructed this way brought to life for nineteenth-century viewers the western pioneer experience.

Other images of western migration included George Caleb Bingham’s Daniel Boone Escorting Settlers through the Cumberland Gap, (1851–1852).

Truettner describes Daniel Boone as the quintessential pioneer, whose energy and resourcefulness helped him to build a generous livelihood from a succession of wilderness homesteads. His image had become a national symbol exemplifying the spirit of adventure and accomplishment. But Boone’s initial visit to Kentucky, Truettner explains, was prompted by real-estate speculation. He writes, “…in fact [these men] were no more than commercial vanguards. They were trespassers on foreign territory who began the process of separating Indians from their land. These images communicated that opportunities on the frontier awaited everyone and perpetuated the myth that the settling of the west was peaceful, when in reality it was bitterly contested every step of the way.”[3]

“Inventing ‘The Indian’”

The exhibition's third section used several rooms to group three different and conflicting stereotypes of native Americans, which were thematically subtitled as the Noble Savage, the Threatening Savage and the Vanishing Race.[9]

Combined sample portraits with revisionist text informed by Richard A. Slotkin’s book, Regeneration Through Violence: The Mythology of the American Frontier, 1600–1860 (1973) and Richard Drinnon’s Facing West: The Metaphysics of Indian-Hating and Empire building (1980) generated so much antagonism that Truettner voluntarily revised about ten of the fifty-five labels in an effort to tone down the message and to please anthropologists.[2]

Truettner’s original label read, “This predominance of negative and violent views was a manifestation of Indian hatred, a largely manufactured, calculated reversal of the basic facts of white encroachment and deceit.” Truettner eliminated this sentence from the revised text. Another label stated, “These images give visual expression to white attitudes toward Native peoples who were considered racially and culturally inferior.” The edited version of this label read, “These images give visual expression to white attitudes toward Native peoples." Truettner explained in an oral interview with Andrew Gulliford that he made changes to the text because he “wanted to catch visitors, not alienate them” and because he believes “in communicating with the larger museum audience.”

Charles Bird King painted noble images of Indians as seen in Young Omahaw, War Eagle, Little Missouri and Pawnees (1822).

Text labels read,

“Artistic representations of Indians developed simultaneously with white interest in taking their land. At first, Indians were seen as possessing nobility and innocence. This assessment gave way gradually to a far more violent view that stressed hostile savagery…apparent in contrasting works…”[7]

Charles Deas’ The Death Struggle (1845), depicts a white man and a Native American locked in mortal combat and tumbling over a cliff.

The text labels read,

“Indians were inevitably represented as hostile aggressors at the very moment settlers and the army were invading their land. Such a patent change of image tells us that white artists were presenting a stereotype rather than a balanced view of Indian life.”[7]

In Tompkins H. Matteson’s The Last of the Race (1847), Truettner writes, “Violent encounters were not the only means of “solving the Indian problem.”[3] Truettner adds both Matterson’s The Last of the Race (1847) and John Mix Stanley's Last of Their Race (1857) "suggested Indians would eventually be buried under the waves of the Pacific.”[3]

Another series of paintings represented acculturation themes that predicted Indians would be peacefully absorbed into white society, thereby neutralizing “aggressive” racial characteristics.” Charles Nahl’s Sacramento Indian with Dogs (1867) was among this group of paintings.[3]

Truettner concludes, “The myth in this case denies the Indian problem by solving it two ways: those who could not accept Anglo-Saxon standards of progress were doomed to extinction.”[3]

“Settlement and Development: Claiming the West”

The fourth section included paintings that portrayed the successful lives of miners and settlers and depicted the give-and-take of American frontier democracy. Also included were popular culture and advertising images.[2]

Works in this section included, George Caleb Bingham’s Stump Speaking (1853–1854), John Mix Stanley’s Oregon City on the Willamette River (1850–1852), Charles Nahl and Frederick August Wenderoth, Miners in the Sierras (1851–1852), Mrs. Jonas W. Brown, Mining in the Boise Basin in the Early Seventies (circa 1870–80), George Caleb Bingham’s Canvassing for a Vote (1851–52), and George W. Hoag’s Record Wheat Harvest (1876).

Truettner writes these works, “.... support the myth that there was enough for everyone. Cities were models of organization and industry, exploitation of land and natural resources is featured with engaging naiveté, and industrial pollution is offered as a picturesque accessory to the landscape. These paintings convert frontier life to a national idiom of prosperity and promise.”[3]

“ ‘The Kiss of Enterprise’: The Western Landscape as Symbol and Resource”

The fifth section focused on a series of landscapes that represented in succession, the Green River Bluffs of Wyoming, the Colorado River, the Grand Canyon, the Donner Pass and the big trees of California, which portrayed the west as both edenic wonders and emblems of national pride.[3]

According to Truettner, the market for scenes of commerce and industry coexisted with a "taste for heroic landscape" and included photographs and paintings of the western landscape as both symbol and exploitable resource. The images of the vast west meant to serve as a promotion to inspire further migration. Photographs chronicle the building of railroads and depict black steam engines traveling through the Rocky Mountains[2]

Works in this section included Oscar E. Berninghaus’ A Showery Day, Grand Canyon (1915), Andrew Joseph Russell’s, Temporary and Permanent Bridges and Citadel Rock, Green River (1868) Albumen print, Thomas Moran's, The Chasm of the Colorado (1983–84), Albert Bierstadt’s Donner Lake from the Summit (1873), as well as commercial landscapes and advertising images by unidentified artists, entitled Splendid (1935) and Desert Bloom (1938).

“Doing the ‘Old American’: The Image of the American West, 1880– 1920.”

With the first five sections serving as metaphors of progress, the sixth and last section took the exhibit in a different direction and was deemed by many critics as the most controversial phase of the exhibition.

Truettner explained that the ideology used to justify expansion had suddenly achieved permanent status and without more frontier left to conquer, artists and their images were now called on to relay the ideology of the past to future generations. Truettner claims the images in this section "speak not to the actual events but to the memory of those events and its impact to future audiences."[3]

Critics saw this as the curator’s attempt to deny the art of Frederic Remington, Charles Schreyvogel, Charles Russell and Henry Farny had any basis in western realism and their images were merely products of composite sketches based on photographs.[10]

Attempting to place these artists of western frontier images in an eastern urban context, the exhibit label states, “Although they reveal isolated facts about the West, the paintings in this section reveal far more about the urban, industrial culture in which they were made and sold.”[2]

William Truettner writes in the show's catalog that when artist Charles Russell was asked who purchased his paintings the Montana artist explained in 1919 that his paintings were purchased by “Pittsburghers most of all. They may not be so strong on art but they are real men and they like real life.”[3]

Other works included Charles Russell’s Caught in the Circle (1903), and For Supremacy (1895), Charles Schreyvogel’s Defending the Stockade (circa 1905), and Henry Farny’s The Captive (1885).

Another painting entitled, The Captive (1892), by Irving Couse, generated a lot of critical reviews. Roger B. Stein writes, "The much disputed critical reading of Irving Couse's The Captive (1892), an image of an old chief with his young white “victim,” raised explicit questions about the intersection of gender and race and the function of the gaze in constructing meaning in this troubled emotional and cultural territory in a way that shocked viewers because it had not been prepared for earlier." Stein adds,

"The curatorial experiment failed not because what the textblock said was untrue (though it was partial, inadequate and rhetorically over-insistent) but because the significant verbal comment on gender had been withheld until the last room of the exhibit. Visually, The West As America was a fascinating study of gender issues from the first Leutze images forward. One may legitimately reply that gender was not the intellectual territory which this exhibition staked out in its verbal script, but my argument here is based upon the premise that a museum exhibition is – or ought to be – first and last a visual experience (the book or catalog is another and different mode of communication)."[9]

The label read,

“From Puritan cultures onwards, the captivity theme had been an occasion for white writers and artists to advocated the “unnaturalness” of intermarriage between races. Couse’s painting is part of this tradition.The painting establishes two “romances.” The first – suggested but not denied – is between the woman and the Indian. The two figures belong to different worlds that cannot mix except by violence. (Note the blood on the woman’s left arm). The second romance is between the woman and the viewer of the painting, implicitly a white man, who is cast in the heroic role of rescuer. This relationship is the painting’s “natural” romance.

These two conflicting romances account for the ironic combination of chastity and availability encoded by the woman’s body. The demure turn of her head shows that she has turned away from the Indian. Yet this very gesture of refusal is also a sign of her availability: she turns toward the viewer. It is by her role as sexual stereotype that the woman in Couse’s painting is really captive.”[9]

The label also went on to suggest than an open teepee flap implied sexual encounter and arrow shafts become phallic objects.[2]

Reaction

Political issues

The West as America coincided with the final phase of the Gulf War in 1991. According to reviewers in the media, for those who understood the war as a triumph of American values, the exhibition’s critical stance toward western expansion seemed like a full-blown attack on the nation’s founding principles.[12] The language of the show, while not the curator’s goal, "played into the hands of those who would equate cultural criticism with national betrayal."[2]

In a book for comments by visitors, historian and former Librarian of Congress, Daniel Boorstin wrote that the exhibition was “...a perverse, historically inaccurate, destructive exhibit…. and no credit to the Smithsonian.”[2] Daniel Boorstin’s comment prompted Senior Republican Senator from Alaska Ted Stevens and Senator Slade Gorton from Washington, two senior members of the Senate Appropriations Committee, to expresse outrage over the exhibit and to threaten to cut funding to the Smithsonian Institution.[13]

By appealing to patriotism, the Senators used funding of the Smithsonian as an opportunity to criticize the "dangers of liberalism." Stevens argued that the institutional guardians of culture – the federally funded Smithsonian and other related federally funded arts programs in general – had become "enemies of freedom."[14]

According to the Senators, the problem with The West As America as well as other curatorial controversies produced by the Smithsonian and the National Endowment for the Arts such as the Mapplethorpe and Andre Serrano photographs, was that it “breeds division within our country.”[14]

Citing two other Smithsonian projects, a documentary about the Exxon Valdez oil spill and a television series about the founding of America that was reported to accuse the United States of genocide against the Indians, Steven’s warned Robert McAdams, the head of the Smithsonian that he was "In for a battle.” In a reference to the funding of the Smithsonian, which in part is regulated by the Senate Appropriations Committee, Steven's added, “I’m going to get other people to help me make you make sense.”[13]

To many in the national press and the museum community, the Senators’ attack on the Smithsonian and the exhibition at the National Museum of American Art was one movement in a larger effort to transform culture into a “wedge issue.”[14] The term, often used interchangeably with “hot button issue” is used by politicians to exploit issues using highly contentious “loaded language” to divide the opposing voter base and to galvanize a large electorate around the issue. “Political correctness” became another expression used frequently in the debate.

The use of words and phrases in the exhibit’s text labels such as “race,” “class,” and “sexual stereotype”, allowed critics of so-called “multicultural education” to condemn the show as “politically correct.” In the mind of the critics, the exhibition served as proof that multicultural education had spread from the campuses to the Smithsonian.[12]

The Wall Street Journal, in an editorial entitled, "Pilgrims and Other Imperialists”, labeled the exhibition “an entirely hostile ideological assault on the nation’s founding and history.” Syndicated columnist Charles Krauthammer condemned the exhibition as “tendentious, dishonest, and finally, puerile” and called it “the most politically correct museum exhibit in American history.”[2]

Comments in the museum's guestbook show that for many of the exhibition’s younger supporters, asking questions about western images seemed not only correct but even the obvious thing to do.[12]

In a hearing of the Senate Appropriations Committee on May 15, 1991, Stevens criticized the Smithsonian for demonstrating a "leftist slant" and accused The West As America of having a "political agenda" citing the exhibition’s 55 text cards accompanying the artworks as a direct rejection of the traditional view of United States history as a triumphant, inevitable march westward.[5]

The head of the Smithsonian, Robert McAdams, responded to the attack by saying he welcomed an inquiry, which he hoped would allay concerns and added, “I don’t think the Smithsonian has any business, or ever had any business, developing a political agenda.”[5]

Senator Steven’s called the show “perverted” but later conceded to Newsweek magazine he had not actually seen the exhibit on the West but had ..."merely been alerted by the comment posted by Daniel Boorstin in the museum’s guestbook."[13]

Public commentary

There were more than 700 visitor comments recorded in the museums guestbook in Washington, DC, generating three large volumes of commentary. Viewers passed judgment on the works, the curator’s competence, and the tone of the explanatory texts, previous comments in the comment book and local reviews of the exhibition.

Praise dominated the criticism – 510 of the 735 comments were generally positive.[12] One hundred and ninety-nine people signaled out the wall texts for praise, while 177 felt negatively about them.[15]

Those disagreeing with the text generally thought the images should be allowed to speak for themselves and felt even without the text explanations, the images would reveal a truthful account of westward expansion. The opposing group, some of whom still objected to the texts, agreed the images misrepresented history in that they cast the westward movement as too much of a heroic odyssey.[12]

One commentary typical of those disagreeing with the texts read,

“The “reinterpretations” accompanying these great paintings go too far. Too much supposition in artistic intent. Granted wasn’t all a “dream,” and inequalities were there – but it took guts and spirit to go westward.” (Signed DC)[15]

Another viewer offered,

“I always thought painting was supposed to be about hopes, dreams, the imagination. Instead, you seem to say it’s political statement at every brushstroke. Your tendentious opinions betray a lack of understanding of the artist and a blindness to the paintings themselves. Every painting is, according to you, an evil, cunning, greedy “Anglo-American.” Shame on you for choosing to make a statement (a very limited statement) about your “political correctness” instead of really looking at the art for what it says about the appeal of the West to our collective imagination. Art is bigger than everyday logic.” (Signed VC, Alexandria, VA)[15]

Those defending the exhibit wrote,

“It’s refreshing to see an exhibit on early U.S. history which includes the atrocities that were performed on the native or “original” North American populations. Thank you for challenging the mythology of white supremacy. The paintings are truly interpretative, and without the commentary and discussion that was included alongside the paintings, visitors would not necessarily consider all sides of the westward expansion.” (Signed IN, Washington, DC)[15]

“….myths of the conquest of the West as being peaceful and full of promise with justice for all were horribly false…” (Signed DC Great Falls, VA)[15]

Some viewers had mixed feelings.

“The art is terrific. The labels are propaganda – distortions in the name of “multicultural” education. (Signed, PL, New York, NY)[15]

Some commented on others' comments.

“I found several of the political commentaries thought provoking (e.g., the reading of the woman’s position in The Captive). Others seem less convincing, as in the commentary about the presence or absence of Native Americans. Painters are condemned for omitting the Native Americans (as in The Grayson Family). But they are also condemned for portraying them. I leave the exhibit with the sense that the painters could not have done anything right, and I think the exhibit should address that question.” (Signed, JM, University of North Carolina).[15]

Attendance and exhibition cancellations

The show was scheduled to run from March 15 – July 7, 1991, but was extended an additional 13 days to accommodate a growing audience. Attendance to the NMAA increased by 60% over the same period the previous year.[2]

While praise dominated the comments in the guest book in Washington, DC, show promoters were denied the opportunity to measure the variety and intensity of reaction in the West because of the cancellation of two proposed exhibit tours at the St. Louis Art Museum and the Denver Art Museum.[1] The cancellations were not due to the controversy, but rather a result of the continuing recession and the $90,000 participation fee, which was only part of a total estimated cost of $150,000 per site.[2]

Legacy of the exhibition

Government funding

This debate surrounding The West as America raised questions about the government’s involvement in the arts and whether public museums were able or unable to express ideas that are critical of the United States without the risk of being censured by the government.

The Smithsonian Institution receives funding from the United States Government through the House and Senate Interior, Environmental and Related Agencies Appropriation subcommittees.[16] The Smithsonian is approximately 65% federally funded. In addition, the Smithsonian has trust funds, contributions from corporate, foundation and individual sources and it generates revenue from Smithsonian Enterprises, which include stores, restaurants, Imax theaters, gifts and catalogs.[17]

The West as America cost $500,000 and was covered with private money.[5] At the time of exhibit in 1991, the Smithsonian received about $300 million in federal funds.[13] Federal funding to the Smithsonian has increased by 170.5% over the last 21 years with funding for 2012 totaling $811.5 million.

Total funding of arts-related federal programs in 2011 totaled just over $2.5 billion. The Smithsonian Institution continues to receive the biggest federal arts allocation, receiving $761 million in 2011. The Corporation for Public Broadcasting received $455 million in 2011 (of which about $90 million goes to radio stations). With the total federal budget for fiscal year 2011 of $3.82 trillion, federal arts funding accounts for approximately 0.066% (sixty-six one-thousandths of one percent) of the total federal budget.[18]

The Smithsonian’s federal appropriation for 2012 of $811.5 million represents an increase of $52 million above its 2011 appropriation.[19] The requested budget for the fiscal year 2013 is $857 million, a $45.5 million increase over 2012 funding. With a fiscal year 2013 total federal budget of $3.803 trillion, Smithsonian funding represents .00023% (twenty-three hundred-thousandths of one percent) of the total 2013 federal budget.[20]

Artists

- Thomas Allmond Ayres, Painter, Illustrator

- Edward O. Beaman, Photographer

- James Henry Beard, Painter

- Joseph Hubert Becker, Painter, Illustrator

- Oscar Edmund Berninghaus, Painter

- Albert Bierstadt, Painter

- Charles Bierstadt, Photographer

- George Caleb Bingham, Painter

- Karl Bodmer, Painter, Lithographer

- William Josiah Brickey, Painter

- Valentine Walter Bromley, Painters, Draftsman

- Margaretta (Maggie) Favorite Brown, Painter (aka Mrs. John W. Brown, Mrs. Jonas)

- George de Forest Brush, Painter

- Elbridge Ayer Burbank, Painter

- John Burgum, Painter

- George Catlin, Painter

- John Gadsby Chapman, Painter, Illustrator

- Frederic Edwin Church, Painter

- Eanger Irving Couse, Painter

- Sallie Cover, Painter (aka Mrs. Ferdinand Cover)

- Charles C. Curtis, Photographer

- Charles Deas, Painter

- Seth Eastman, Painter

- Alexander Edouart, Painter, Photographer

- Augustus William Ericson, Photographer

- Henry Francis Farny, Painter, Illustrator

- James Earle Fraser, Sculptor

- Paul Frenzeny, Draftsman

- William Fuller, Painter

- John Gast, Painter, Lithographer

- Sanford Robinson Gifford, Painter

- Carl William Hahn, Painter

- Alfred A. Hart, Painter, Photographer

- Andrew Putnam Hill, Painter, Photographer

- Thomas Hill, Painter

- John K. Hillers, Photographer

- William Henry Holmers, Painter, Draftsman

- William Henry Jackson, Photographer

- William Smith Jewett, Painter

- Theodor Kaufman, Painter

- William Keith, Painter

- Charles Bird King, Painter

- Olof Krans, Painter (aka Olaf Olofson)

- Joseph Lee, Painter

- Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze, Painter

- Hermon Atkins MacNeil, Sculptor, Painter

- Tompkins Harrison Matteson, Painter

- Andrew W. Melrose, Painter

- Alfred Jacob Miller, Painter

- Thomas Moran, Painter, Illustrator

- William Sidney Mount, Painter

- Joseph Mozier, Sculptor

- Charles Christian Nahl, Painter, Illustrator

- Ernest Marjot, Painter (aka Erneste-Etienne de Franceville Narjot)

- Thomas Nast, Painter, Illustrator, Cartoonist

- Victor Nehlig, Painter

- Timothy O'Sullivan, Photographer

- Thomas Proudly Otter, Painter, Engraver

- Frances (Fanny) Flora Bond Palmer, Watercolorist, Lithographer

- Marie-Adrien Persac, Painter, Lithographer

- Frederick Augustus Ferdinand Pettrich, Sculptor (aka Ferdinand Pettrich)

- Alexander Phimister Proctor, Sculptor, Painter

- William Tylee Ranney, Painter

- Frederic Sackrider Remington, Painter, Sculptor, Illustrator

- Peter Rindisbacher, Painter

- Peter Frederick Rothermel, Painter

- Andrew Joseph Russell, Photographer

- Charles Marion Russell, Painter, Sculptor

- Charles Schreyvogel, Painter

- Joshua Shaw, Painter

- Otto Sommer, Painter

- John Mix Stanley, Painter

- Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait, Painter, Illustrator

- Jules Tavernier, Painter, Illustrator

- George Tirrell, Painter (aka John Tirrell)

- Domenico Tojetti, Painter

- Leon Trousset, Painter

- James Walker, Painter

- Carleton Eugene Watkins, Photographer

- John Ferguson Weir, Painter

- Robert Walter Weir, Painter

- Frederick August Wenderoth, Painter

- Thomas Worthington Wittredge, Painter

- Karl Ferdinand Wimar, Painter

- Richard Caton Woodville, Painter

- Newll Convers Wyeth, Painter, Illustrator

See also

- American Old West

- The Old West

- The Smithsonian Institution

- The National Museum of American History

- Manifest Destiny

- Revisionist Western

- Western Expansion of the United States

- Patronage

- Arts Funding

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Price, Byron B. (May 1993). "Cutting for Sign: Museums and Western Revisionism". The Western Historical Society. 24 (2): 229–234. Retrieved 03/05/12. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)(registration required) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Gulliford, Andrew (June 1992). "The West As America: Reinterpreting Images of the Frontier 1820–1920". The Journal of American History. 79 (1): 199–208. doi:10.2307/2078477. JSTOR 2078477.(registration required)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Truettner, William H., ed. (1991). The West As America: Reinterpreting Images of the Frontier, 1820–1920. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institutional Press. ISBN 1-56098-023-0.

- ↑ Wallach, Alan (1998). Exhibiting Contradiction. Amherst, Mass.: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 105–117. ISBN 978-1558491175.

- 1 2 3 4 Kimmelman, Michael (1991-05-26). "Old West, New Twist at the Smithsonian". The New York Times. Retrieved 03/08/12. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Deverell, William (Summer 1994). "Fighting Words: The Significance of the American West in the History of the United States.". The Western Historical Quarterly. 25 (2): 185–206. Retrieved 03/05/12. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)(registration required) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wood, Mary. "The West As America:Reinterpreting Images of the Frontier, 1820–1920". University of Virginia. Retrieved 03/17/12. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ [. http://people.virginia.edu/~mmw3v/west/teacher.htm "The West As America, "A Guide for Teachers""] Check

|url=value (help). National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Museum. - 1 2 3 4 Stein, Roger B. (Summer 1992). "Visualizing Conflict in "The West As America"". The Public Historian. 14 (3): 85–91. doi:10.2307/3378233. Retrieved 03/05/12. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)(registration required) - 1 2 3 Panzer, Mary (1992). "Panning 'The West As America': or Why One Exhibit Did Not Strike Gold". Radical History Review. 52: 105–113. doi:10.1215/01636545-1992-52-105. Retrieved 03/05/12. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)(registration required) - ↑ Trachtenberg, Alan (Sep 1991). "Contesting the West". Art In America. 79 (9): 118.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Truettner, William H.; Alexander Nemerov (Summer 1992). "What You See is Not Necessarily What You Get: New Meaning in Images of the Old West". The Magazine of Western History. 42 (3): 70–76. Retrieved 03/05/12. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)(registration required) - 1 2 3 4 Thomas, Evan (1991-05-26). "Time to Circle the Wagon". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 03/17/12. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - 1 2 3 Wolf, Bryan J. (Sep 1992). "How The West Was Hung, Or, When I Hear the Word "Culture" I Take Out My Checkbook". American Quarterly. 44 (3): 418–438. doi:10.2307/2712983. Retrieved 03/05/12. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)(registration required) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 [“Showdown at “The West As America Exhibition.” American Art 5, no 3 (Summer 1991): 2–11 http://www.jstor.org/stable/3109055 (accessed March 5, 2012)

- ↑ "Smithsonian Institution FY'08 Funding". The National Coalition for History.

- ↑ "Facts About the Smithsonian". Newsdesk, Newsroom of the Smithsonian Institution. 02/01/11. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Anderson, Aaron. "Federal Arts Funding: A Trace Ingredient in the Sausage Factory of Government Spending". createquity.com. Retrieved 03/08/12. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Smithsonian Fiscal Year 2012 Federal Appropriation Totals $811.5 Million". Newsdesk, Newsroom of the Smithsonian Institution. 12/27/11. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Smithsonian fiscal year 2013 Budget Request Totals $857 Million". Newsdesk, Newsroom of the Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 03/08/12. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)