Theodor de Bry

| Theodor de Bry | |

|---|---|

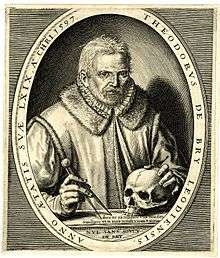

An engraved self-portrait of Theodorus de Bry. He is dressed in work costume, with a flange goffered on a collar of fur, one hand holding a compass while the other rests on a human skull, both signs of erudition at that time. The Latin words registered on the table are: "Domine, doce me ita reliquos vitae meae dies transigere ut in vera pietate vivam et moriar." ("Lord, teach me to pass the remaining days of my life such that I live and die in true piety.") Just below these words is the motto of the de Bry family: "Nul sans soucy." ("None without worry.") | |

| Born |

1528 Liège |

| Died |

27 march 1598 Frankfurt |

| Known for | Engraving |

| Notable work | Collectiones peregrinatiorum in Indiam orientalem et Indiam occidentalem (1590–1633) |

Theodorus de Bry (also Theodor de Bry) (1528 – 27 March 1598) was an engraver, goldsmith, editor and publisher, famous for his depictions of early European expeditions to the Americas. The Spanish Inquisition forced de Bry, a Protestant, to flee his native, Spanish-controlled Southern Netherlands. He moved around Europe, starting from the city of Liège in the Prince-Bishopric of Liège (where he was born and grew up), then to Strasbourg, Antwerp, London and Frankfurt, where he settled.

De Bry created a large number of engraved illustrations for his books. Most of his books were based on first-hand observations by explorers, even if De Bry himself, acting as a recorder of information, never visited the Americas. To modern eyes, many of the illustrations seem formal but detailed.

Life

Theodorus de Bry was born in 1528 in Liège, Prince-Bishopric of Liège, now in Belgium, to a family which had escaped the destruction of the city of Dinant in 1466 during the Liège Wars by the Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good and his son Charles the Bold. As a man he trained under his grandfather, Thiry de Bry the Elder (? - 1528), and under his father, Thiry de Bry the Younger (1495–1590), who were jewellers and engravers, engraving copper plates. The art of copper plate engraving was the technology required at that time for printing images and drawings as part of books. In 1524 Thiry de Bry the Younger married Catherine le Blavier, daughter of Conrad le Blavier de Jemeppe. Their son, Theodore de Bry, also became a jeweller and engraver.

Theodore de Bry became a Protestant, and in 1570 was sentenced to perpetual banishment and his goods were confiscated.[1] He moved to Strasbourg, along the west bank of the Rhine. In 1577, he moved to Antwerp in the Duchy of Brabant, which was part of the Spanish Netherlands or Southern Netherlands and Low Countries of that time (16th century), where he further developed and used his skills as a copper engraver. Between 1585 and 1588 he lived in London, where he met the geographer Richard Hakluyt and began to collect stories and illustrations of various European explorations, most notably from Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues.

In 1588, Theodorus and his family moved permanently to Frankfurt-am-Main, where he became citizen and began to plan his first publications. The most famous one is known as Les Grands Voyages, i.e., "The Great Travels", or "The Discovery of America". He also published the largely identical India Orientalis series, as well as many other illustrated works on a wide range of subjects. His books were published in Latin, and were also translated into German, English and French to reach a wider reading public.

In 1590 Theodorus de Bry and his sons published a new, illustrated edition of Thomas Harriot's A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia about the first English settlements in North America (in modern-day North Carolina). His illustrations were based on the watercolor paintings of colonist John White.[3] The book sold well, and the next year de Bry published a new one about the first French attempts to colonize Florida: Fort Caroline, founded by Jean Ribault and René de Laudonnière. It featured 43 illustrations based on paintings of Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, one of the few survivors of Fort Caroline. Jacques de Moyne had planned to publish his account of his expeditions but died 1587. According to de Bry's account, he had bought de Moyne's paintings from his widow in London and used them as a basis for the engravings.

He and his son John-Theodore made adjustments to both the texts and the illustrations of the original accounts, on the one hand in function of his own understanding of Le Moyne's paintings, and, most importantly, to please potential buyers. The Latin and German editions varied markedly, in accordance with the differences in estimated readership.

The verisimilitude of many of de Bry's illustrations is questionable; not least because he never crossed the Atlantic. Amerindians look like Mediterranean Europeans, and illustrations mix different tribal customs and artifacts. In addition to day-to-day life of the American natives, Theodore de Bry even included a few depictions of cannibalism. All in all, the vast amount of these illustrations and texts influenced the European perception of the New World, Africa, and Asia.

Among other works he engraved a set of twelve plates illustrating the Procession of the Knights of the Garter in 1587, and a set of thirty-four plates illustrating the Procession at the Obsequies of Sir Philip Sidney; plates for Thomas Harriot's Brief and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (Frankfurt, 1590); the plates for the six volumes of Jean-Jacques Boissard's Romanae Urbis Topogrephia et Antiquitates (1597–1602); and, with Boissard, a series of 100 portraits and biographies of humanists and Protestants entitled Icones Virorum Illustrium (1597–1599).

De Bry had been assisted by his two sons, Johann Theodor de Bry (1561–1623) and Johann Israel de Bry (1565–1609), who after their father's death in Frankfurt-am-Main on 27 March 1598, carried on the Collectiones (expanded to voyages in Asia, reaching 30 volumes) and the illustration of Boissard's work and also added to the Icones and other significant publications, like Robert Fludd's works on the microcosm and macrocosm.

His work and engravings can today be consulted at many museums around the world, including Liège, his birthplace, and at Brussels in Belgium. In France, they are housed at the Library of the Marine Historical Service at the Château de Vincennes on the outskirt of Paris. In the USA, there are copies at the Public Library of New York, at the University of California at Los Angeles, and elsewhere. In Argentina, it is possible to find copies at the Museo Maritimo de Ushuaia in Tierra del Fuego and at the Navy Department of Historic Studies in Buenos Aires. In Scotland, eleven titles are listed in the catalogue of Edinburgh University Library (Special Collections).

Works

- 1590–1634 Bry (Theodore de). Collectiones peregrinatiorum in Indiam orientalem et Indiam occidentalem, XIII partibus comprehenso a Theodoro, Joan-Theodoro de Bry, et a Matheo Merian publicatae. Francofurti. 1590-1634. Fol. (Parts I to VI, edited and illustrated by T. de Bry, parts VII to IX by his sons, Johann Theodor and Johann Israel de B.; parts X to XII by J. T. de B., and part XIII by M.Merian.)

- 1596 (America. Part VI.) Historiae ab A. Bezono ... scriptae, sectio tertio....in hac reperies qua natione Hispani... Peruani regni provincias occuparint, capto rege Atabaliba, etc. (3d part of G. Benzoni's Historia del Mondo Nuovo.) Map and plates, 2 parts. Frankfurt. 1596. Fol.

- 1617 (Second edition). Oppenheimii. 1617. Fol.

- 1595 (German edition). Frankfurt. 1595. Fol.

- 1613 (Second German edition). Frankfurt. 1613. Fol.

- 1599 (America. Part VII). Descriptionem trium itinerum. . .equitis F. Draken....J. Hauckens.. .G. Ralegh ... in Latinum sermonem conversaauctore G. Artus. Maps and plates. 3 pt. Francofurti. 1599. Fol.

- 1625 (Second edition). Francofurti. 1625. Fol.

- 1602 (America. Part IX). De novi orbis natura (by J.de Acosta). Accessit... S. de Weert and...O. a. Noort ....Plates. 5 pt. Francofurti. 1602. Fol.

- 1633 (Second edition). Francofurti. 1633. Fol.

- 1601 (German edition). Yon Gelegenheit der elemente natur de Neuer Welt. J. H. v. Linschoten. Frankfurt. 1601. Fol.

- 1602 (Latin and German edition). Francofurti. 1602.

- 1620 (Latin). Francofurti. 1634. Fol.

See also

References

- ↑ A. Siret, "Bry (Théodore de)", Biographie Nationale de Belgique, vol. 3 (Brussels, 1872), 125–128.

- ↑ Theatres of Cruelty: Wars of Religion, Violence, and The New World Commentary by Tom Conley, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, The Newberry Library, 1990

- ↑ http://www.virtualjamestown.org/images/white_debry_html/jamestown.html

- Lauren Beck, "Illustrating the Conquest in the Long Eighteenth Century: Theodore de Bry and His Legacy," in Book Illustration in the Long Eighteenth Century: Reconfiguring the Visual Periphery of the Text, Ed. Christina Ionescu. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2011, 501-40.

- M. Bouyer & J.-P. Duviols, Le Théâtre du Nouveau Monde: Les grands Voyages de Théodore de Bry (Gallimard, 1992). ISBN 2-07-056509-2

- Bernadette Bucher, Icon and Conquest: A Structural Analysis of the Illustrations of the de Bry's Great Voyages (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1981). ISBN 0-226-07832-9 (translated from the French edition, La Sauvage aux seins pendants. Paris: Hermann, 1977. ISBN 2-7056-5845-9)

- Michiel van Groesen, The Representations of the Overseas World in the De Bry Collection of Voyages (1590-1634) (Leiden/Boston 2008)

- Thomas Harriot, A briefe and true Report of the new found Land of Virginia: The complete 1590 edition with 28 engravings by Theodor de Bry, after the drawings of John White and other illustrations, with a new introduction by Paul Hulton of the British Museum (Dover Publications, 1972). ISBN 0-486-21092-8

- Henry Keazor: "Theodore De Bry's Images for America", Print Quarterly 15/2 (1998), pp. 131–149

- Henry Keazor: "'Charting the autobiographical, selfregarding subject'? Theodor De Brys Selbstbildnis", in: Berichten, Erzählen, Beherrschen - Wahrnehmung und Repräsentation in der frühen Kolonialgeschichte Europas, hrsg. von Susanna Burghartz, Maike Christadler und Dorothea Nolde (= Zeitsprünge - Forschungen zur Frühen Neuzeit, Band 7, Heft 2/3), Frankfurt am Main 2003, p. 395 - 428

- Jerald T. Milanich, "The Devil in the Details", Archaeology magazine May/June 2005

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bry, Theodorus". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bry, Theodorus". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - Archives of the de Bry family.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Bry, Theodorus. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Theodor de Bry. |

- Théodore de Bry of Liège: portrait, biography, masterpieces (in French).

- Les collections artistiques de l'Université de Liège

- La Renaissance liègeoise et la lutte contre la réforme (in French)

- Theodore de Bry and his illustrated Voyages and Travels

- Contents of Grands Voyages, by Theodore de Bry. German and Latin Editions.

- De Bry's Grand Voyages. Early Expeditions To The New World.

- The Roanoke Colony of "Virginia" from De Bry's Grand Voyages.

- Index of White watercolors/De Bry Engravings

- Picturing the new World: Hand-colored DeBry Engravings of 1590.

- Grand Voyages prints Birmingham Public Library (Alabama)

- Johan Theodor de Bry in Rijksmuseum

- One of the largest collection of de Brys prints available to date