Theora mesopotamica

| Theora mesopotamica | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

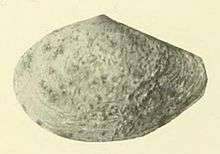

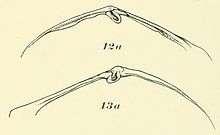

| Right (above) and left (below) valves, from Annandale 1918. Images are to scale with each other. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Bivalvia |

| Subclass: | Heterodonta |

| Order: | Veneroida |

| Superfamily: | Tellinoidea |

| Family: | Semelidae |

| Genus: | Theora |

| Species: | T. mesopotamica |

| Binomial name | |

| Theora mesopotamica (Annandale, 1918) | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Corbula mesopotamica Annandale, 1918 | |

Theora mesopotamica is a species of saltwater and brackish water clam, a bivalve mollusk in the family Semelidae. This species is known from the northwestern end of the Persian Gulf, and from subfossil remains in brackish deposits in the lower Tigris–Euphrates basin of Iraq.

Taxonomy

In 1918, this species was first described by Nelson Annandale, from specimens collected by W. H. Lane, which were placed in the Indian Museum. Annandale named the species Corbula (Erodona) mesopotamica, believing it to belong in the subgenus Erodona within the genus Corbula. Annandale believed this bivalve was most similar to Corbula pfefferi (now Potamocorbula abbreviata),[2] an Indian species.[3] The species epithet mesopotamica refers to the species having been found in the Mesopotamian region.

In 1957, F. E. Eames and G. D. Wilkins, biologists working for British Petroleum, described a new species with the name Abra cadabra.[4] Eames later told S. Peter Dance that he chose the name because, as a species known from subfossils, it "had been dead for a long time, and could be described as a cadaver," and as a pun on the familiar magical incantation abracadabra.[5] In 1995, Abra cadabra was moved to the genus Theora by P. G. Oliver.[6] In 2005, J.-C. Plaziat and W. R. Younis discovered that the name was a junior synonym of Annandale's Corbula mesopotamica and those two authors changed the name of the species to the new combination, Theora mesopotamica.[1]

Description

The shell is small and thin, with inequally sized and asymmetric valves. It is about 1.5 times as long as high, rounded in the front, subtruncate behind and moderately swollen in the central region. The umbos are small and point out slightly; they are situated nearer to the anterior than the posterior end. The dorsal margin from the umbo to the upper end of the anterior margin is slightly convex, and from the umbo to the posterior region is straight and sloping. The lower margin is convex and evenly curved, and the surface of the upper part of the shell is striated with fine, irregular, transverse concentric markings. The right valve measures 8.5 mm (0.33 in) in breadth and 5.5 mm (0.22 in) in height, and the right valve 8.0 mm (0.31 in) and 5.4 mm (0.21 in).[7]

Distribution

Although the species was first found only as subfossil remains by Annandale, he believed it was probably not extinct, and that some of the deposits he saw were likely recent in age.[3] Living specimens of the species have since been obtained from the northwestern part of the Persian Gulf,[6] including in "muddy and silty substrates" around Failaka Island of Kuwait.[8]

Within Iraq, Annandale collected his specimens from a sandy lake-bed deposit, in the vicinity of Nasiriyah on the Euphrates.[3] Eames and Wilkins found the species in borings made in the Hammar Marshes, and Plaziat and Younis found it in other localities of the Hammar Formation; they described it as a typical species of this formation. The deposits in Iraq where the species has been found are in brackish habitat (although Annandale believed the deposits to be freshwater, this was due to reworking), toward the outer edge of tidal influence in the Euphrates and Tigris. Much of the species' former habitat, as evidenced by subfossil remains, is now less brackish than it was when the fossils were deposited, meaning it is less likely to be extant in such places.[1]

Ecology

In a study of fish diets in the Khor Al Zubair, this species was one of the two principal species of bivalve found in the stomach contents of common fish such as soles and croakers.[9]

References

- 1 2 3 Plaziat & Younis 2005.

- ↑ Huber 2014.

- 1 2 3 Annandale 1918.

- ↑ Eames & Wilkins 1957.

- ↑ Dance 2009, p. 569.

- 1 2 Oliver 1995, cited in Plaziat & Younis 2005.

- ↑

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a work now in the public domain: Annandale 1918

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a work now in the public domain: Annandale 1918

- ↑ Al-Yamani et al. 2012, p. 216.

- ↑ Nasir 2000, p. 91.

Works cited

- Al-Yamani, Faiza Y.; Skryabin, Valeriy; Boltachova, Natalya; Revkov, Nikolai; Makarov, Mikhail; Grintsov, Vladimir; Kolesnikova, Elena (2012). Illustrated Atlas on the Zoobenthos of Kuwait (PDF) (1st ed.). Kuwait: Kuwait Institute for Scientific Research. ISBN 99906-41-40-4.

- Annandale, N. (1918). "XX. Freshwater Shells from Mesopotamia". Records of the Indian Museum, Calcutta. 15: 159–170.

- Dance, S. Peter (9 May 2009). "A name is a name is a name: some thoughts and personal opinions about molluscan scientific names" (PDF). Zoologische Mededelingen. Leiden: Naturalis Museum. 83 (7): 565–576. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- Eames, F. E.; Wilkins, G. D. (1957). "Six new molluscan species from the alluvium of Lake Hammar near Basrah". Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London. 32 (5): 198–203. (subscription required (help)).

- Huber, M. (2014). "Corbula pfefferi Preston, 1907". World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- Nasir, N. A. (2000). "The Food and Feeding Relationships of the Fish Communities in the Inshore Waters of Khor Al-Zubair, North-West Arabian Gulf" (PDF). Cybium. 24 (1): 89–99.

- Oliver, P. G. (1995). Bosch, D. T.; Dance, S. P.; Moolenbeek, R. G., eds. Seashells of Eastern Arabia. Dubai: Motivate Publishing.

- Plaziat, Jean-Claude; Younis, Woujdan R. (2005). "The modern environments of Molluscs in southern Mesopotamia, Iraq: A guide to paleogeographical reconstructions of Quaternary fluvial, palustrine and marine deposits". Carnets de Géologie (1): 1–18.