Thomas Beddoes

| Thomas Beddoes | |

|---|---|

Thomas Beddoes, pencil drawing by Edward Bird | |

| Born |

13 April 1760 Shifnal |

| Died | 24 December 1808 (aged 48) |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Bridgnorth Grammar School |

| Alma mater | Pembroke College, Oxford, University of Edinburgh |

| Occupation | Physician |

| Known for | History of Isaac Jenkins |

| Spouse(s) | Anna Maria Edgeworth 1773–1824 |

| Children | Thomas Lovell Beddoes |

Thomas Beddoes (13 April 1760 – 24 December 1808) was an English physician and scientific writer. He was born in Shifnal, Shropshire. He was a reforming practitioner and teacher of medicine, and an associate of leading scientific figures. He worked to treat tuberculosis.

Beddoes was a friend of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and, according to E. S. Shaffer, an important influence on Coleridge's early thinking, introducing him to the higher criticism.[1] The poet Thomas Lovell Beddoes was his son. A painting of him by Samson Towgood Roch is in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Life

Beddoes was born in Shifnal on 13 April 1760 at Balcony House. He was educated at Bridgnorth Grammar School and Pembroke College, Oxford. He enrolled in the University of Edinburgh's medical course in the early 1780s.[2] There he was taught chemistry by Joseph Black and natural history by Kendall Walker. He also studied medicine in London under John Sheldon (1752–1808). In 1784 he published a translation of Lazzaro Spallanzani's Dissertations on Natural History, and in 1785 produced a translation, with original notes, of Torbern Olof Bergman's Essays on Elective Attractions.[3]

He took his degree of doctor of medicine at Pembroke College, Oxford University in 1786.

In 1794, he married Anna, daughter of his associate at the Bristol Pneumatic Institution, Richard Lovell Edgeworth. Their son, poet Thomas Lovell Beddoes, was born in 1803 in Bristol.

Career

Beddoes visited Paris after 1786, where he became acquainted with Lavoisier. Beddoes was appointed professor of chemistry at Oxford University in 1788.[4] His lectures attracted large and appreciative audiences; but his sympathy with the French Revolution excited a clamour against him, he resigned his readership in 1792. In the following year he published the History of Isaac Jenkins, a story which powerfully exhibits the evils of drunkenness, and of which 40,000 copies are reported to have been sold.[3]

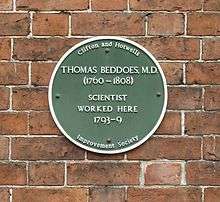

Beddoes addressed tuberculosis, seeking treatments for the disease. He had a clinic in Bristol from 1793 to 1799 and later began the Pneumatic Institution to test various gases for the treatment of tuberculosis. The institution was later changed to a general hospital.

Hope Square, Bristol

Between 1793 and 1799 Beddoes had a clinic at Hope Square, Hotwells in Bristol where he treated patients with tuberculosis. On the principle that butchers seemed to suffer less from tuberculosis than others, he kept cows in a byre alongside the building and encouraged them to breathe on his patients.[5] This became the source of local ridicule, amongst claims that animals were kept in the clinic's bedrooms, against the protests of landlords.[5]

Despite the link he saw between proximity to cows and lower incidence of tuberculosis, he remained sceptical when Edward Jenner began using a cow-derived vaccination for smallpox a few years later.[5]

Bristol Pneumatic Institution

6 Dowry Square, with 7 to the right

While living in Hotwells he began work on a project to establish an institution for treating disease by the inhalation of different gases, which he called pneumatic medicine.[6][7] He was assisted by Richard Lovell Edgeworth. In 1799 the Pneumatic Institution was established at Dowry Square, Hotwells. Its first superintendent was Humphry Davy,[8] who investigated the properties of nitrous oxide in its laboratory. The original aim of the institution was gradually abandoned; it became a general hospital, and was relinquished by its founder in the year before his death.[3]

Beddoes was a man of great powers and wide acquirements, which he directed to noble and philanthropic purposes. He strove to effect social good by popularizing medical knowledge, a work for which his vivid imagination and glowing eloquence eminently fitted him.— Encyc.Brit (1911), [2]

Selected writings

Besides the writings mentioned above, Beddoes was also associated with the following:

- Chemical Essays by Carl Wilhelm Scheele (1786) translator

- An Account of some Appearances attending the Conversion of cast into malleable Iron. In a Letter from Thomas Beddoes, M. D. to Sir Joseph Banks, Bart. P.R.S. (Phil. Trans. Royal Society, 1791)

- Observations on the Nature and Cure of Calculus, Sea Scurvy, Consumption, Catarrh, and Fever (1793)

- Observations on the nature of demonstrative evidence, with an explanation of certain difficulties occurring in the elements of geometry, and reflections on language (1793)

- Political Pamphlets (1795–1797)

- Contributions to Physical and Medical Knowledge, principally from the West of England (1799). In this work (p. 4), Beddoes makes the first recorded use of the word Biology in its modern sense.[9]

- Essay on Consumption (1799)

- Essay on Fever (1807)

- Hygeia, or Essays Moral and Medical (1806)

Beddoes edited the second edition of John Brown's Elements of Medicine (1795).

References

- ↑ Shaffer, E. S. (1980). Kubla Khan and The Fall of Jerusalem. Cambridge University Press. p. 28. ISBN 0521298075.

- 1 2 Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Beddoes, Thomas (1760–1808). Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 614.

- 1 2 3 Chisholm 1911.

- ↑ Cartwright, F.F. (1967). "The Association of Thomas Beddoes, M.D. with James Watt, F.R.S.". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. pp. 131–143. Retrieved 2014-03-11.

- 1 2 3 Mike Jay; John Carey (reviewer) (26 April 2009). "The Atmosphere of Heaven: The Unnatural Experiments of Dr Beddoes and his Sons of Genius". The Sunday Times.

- ↑ Miller, D. P.; Levere, T. H. (2008). ""Inhale it and see?" the collaboration between Thomas Beddoes and James Watt in pneumatic medicine". Ambix. 55 (1): 5–28. PMID 18831152.

- ↑ Stansfield, D. A.; Stansfield, R. G. (1986). "Dr Thomas Beddoes and James Watt: Preparatory work 1794-96 for the Bristol Pneumatic Institute". Medical History. 30 (3): 276–302. doi:10.1017/s0025727300045713. PMC 1139651

. PMID 3523076.

. PMID 3523076. - ↑ Levere, Trevor H (1977). "Dr Thomas Beddoes and the Establishment of His Pneumatic Institution: A Tale of Three Presidents". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 32 (1): 41–49. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1977.0005. PMID 11615622.

- ↑ "biology, n.". Oxford English Dictionary online version. Oxford University Press. September 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-01. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Beddoes, Thomas". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Beddoes, Thomas". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- Barzun, Jacques (1972). Thomas Beddoes M.D. Harper Collins. – essay reprinted in A Jacques Barzun Reader (2002)

Garnett, Richard (1885). "Beddoes, Thomas (1760-1808)". In Stephen, Leslie. Dictionary of National Biography. 4. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

Garnett, Richard (1885). "Beddoes, Thomas (1760-1808)". In Stephen, Leslie. Dictionary of National Biography. 4. London: Smith, Elder & Co. - Jay, Mike (2009). The Atmosphere Of Heaven: The Unnatural Experiments of Dr Beddoes and His Sons of Genius. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12439-2.

- Levere, Trevor H. (1981). "Dr. Thomas Beddoes at Oxford: Radical politics in 1788–1793 and the fate of the Regius Chair in Chemistry". Ambix. 28 (2): 61–69. doi:10.1179/000269881790224318. PMID 11615866.

- Porter, Roy (1992). Doctor of Society: Thomas Beddoes and the Sick Trade in Late Enlightenment England. London: Routledge.

- Robinson, Eric (June 1955). "Thomas Beddoes, M.D., and the reform of science teaching in Oxford". Annals of Science. 11 (2): 137–141. doi:10.1080/00033795500200135.

- Stansfield, Dorothy A. (1984). Thomas Beddoes, M.D., 1760–1808: Chemist, Physician, Democrat. Springer. ISBN 90-277-1686-2.

- Stock, John Edmonds (1811). Memoirs of the Life of Thomas Beddoes, M.D. London: John Murray.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thomas Beddoes. |

- "Thomas Beddoes (1760–1808)". Retrieved 2008-11-09.