Thought Police

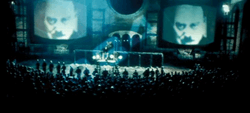

In the novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984), by George Orwell, the Thought Police (Thinkpol in Newspeak) are the secret police of the superstate, Oceania, who are charged with uncovering and punishing "thoughtcrime" and thought-criminals. The Thinkpol use psychological methods and omnipresent surveillance (e.g. telescreens) to search, find, monitor, and arrest citizens of Oceania who would challenge the status quo — the authority of the Party and of Big Brother — even if only with a thought.[1]

George Orwell’s concept of “thought policing” derived from his “power of facing unpleasant facts”, in his criticizism of society’s prevailing ideas — which often placed him in conflict with other people and their “smelly little orthodoxies”.[2]

In Nineteen Eighty-Four

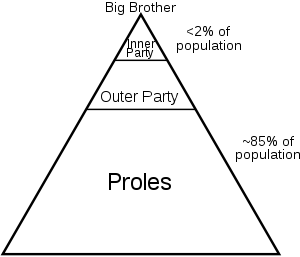

In Orwell's novel, the government (which is dominated entirely by the Inner Party) attempts to control not only the speech and actions, but also the thoughts of its subjects, labeling "unapproved thoughts" with the term thoughtcrime, or crimethink in Newspeak. For such infractions, the Thought Police arrest two characters in the book, Winston and Julia.

Orwell's Thought Police also operate a false resistance movement to lure in disloyal Party members before arresting them. One Thought Police agent, O'Brien, is part of this false flag operation. It is not revealed, however, if a genuine resistance movement actually exists—though the tactic of using a false resistance group called Operation Trust was actually used to lure out dissidents by the State Political Directorate in the Soviet Union.[3][4]

Every Party member has a telescreen in his or her home, which the Thought Police use to observe the populace's actions, looking for unorthodox opinions or an inner struggle. When a Party member talks in their sleep, the words are carefully analyzed. The Thought Police also target and eliminate highly intelligent people, since there is concern they may come to realize how the Party is exploiting them. An example is Syme, a developer of Newspeak, who, despite his fierce devotion to the Party, simply disappears one day.

Winston rebels against the Thought Police by writing "DOWN WITH BIG BROTHER" in his journal (which Party members are not even allowed to have) without knowing it. He attempts to cover up his own thoughts, but believes he will be caught quickly.

The Thought Police generally interfere very little with the working class of Oceania, known as the Proles—although a few Thought Police agents always move among them, spreading false rumors, and identifying and eliminating any individual deemed capable of independent thought or rebellion against the Party, and all Party members live their lives under the constant supervision of the Thought Police.

To remove any possibility of creating martyrs, whose memories could be used as a rallying cause against the Party, the Thought Police gradually wear down the will of political prisoners in the Ministry of Love through conversations, degradation, and finally in a torture chamber known as Room 101. These methods are designed and intended to eventually make prisoners genuinely accept Party ideology and come to love Big Brother, not merely confess. The prisoners are then released back into society for a short while, but are soon re-arrested, charged with new offences, and executed. All other Party members who knew them must forget them, and are prohibited from remembering them by the Thoughtcrime avoiding habit known as "crimestop". All records of the executed prisoners are destroyed and replaced with falsified records by the Ministry of Truth, and their bodies are disposed of by means of cremation.

Other uses

In the first half of the twentieth century, before the 1949 publication of 1984, the Special Higher Police (特別高等警察 Tokubetsu Kōtō Keisatsu or 特高 Tokkō) in Japan were sometimes known as the "Thought Police" (Shiso Keisho).[5]

The term "Thought Police", by extension, has come to refer to real or perceived enforcement of ideological correctness, or preemptive policing where a person is apprehended in anticipation of the possibility that they may commit a crime, in any modern or historical contexts.

In the twenty-first century, a related concept of ideological correctness in reference to the calling out or labeling of words or speech considered by some to be improper or inappropriate is known as "political correctness" (frequently shortened to "PC"). The term has come into the common lexicon.[6][7]

See also

References

| Look up thought police in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- ↑ Taylor, Kathleen. Brainwashing: The Science of Thought Control p. 21. Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-19-920478-0 and ISBN 978-0-19-920478-6.

- ↑ Orwell, George; Orwell, Sonia; Angus, Ian; The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, p. 460; David R. Godine Publisher, 2000; ISBN 1-56792-133-7, ISBN 978-1-56792-133-5

- ↑ Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, The Mitrokhin Archive: The KGB in Europe and the West, Gardners Books (2000), ISBN 0-14-028487-7

- ↑ Pamela K. Simpkins and K. Leigh Dyer, The Trust, The Security and Intelligence Foundation Reprint Series, July 1989.

- ↑ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 113 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ↑ Krugman, Paul (26 May 2012). "The New Political Correctness". New York Times. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ William S. Lind, "The Origins of Political Correctness", Accuracy in Academia, 2000.