Topaz War Relocation Center

|

Central Utah Relocation Center (Topaz) | |

|

Topaz War Relocation Center on March 14, 1943. | |

| Location | Millard County, Utah, United States |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Delta, Utah |

| Built | 1942 |

| Architect | Daley Brothers |

| NRHP Reference # | 74001934 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | January 2, 1974[1] |

| Designated NHL | March 29, 2007[2] |

The Topaz War Relocation Center, also known as the Central Utah Relocation Center (Topaz) and (briefly) the Abraham Relocation Center,[3] was a camp which housed Nikkei – Americans of Japanese descent and immigrants who had come to the United States from Japan. There were a number of such camps used during the Second World War, under the control of the War Relocation Authority.

The camp consisted of 19,800 acres (8,012.8 ha), nearly four times the size of the more famous Manzanar War Relocation Center in California. Most Topaz internees lived in the central residential area located approximately 15 miles (24.1 km) west of Delta, Utah, though some lived as caretakers overseeing agricultural land and areas used for light industry and animal husbandry.

The site is a U.S. National Historic Landmark.[2]

Terminology

Since the end of World War II, there has been debate over the terminology used to refer to Topaz and the other camps in which Americans of Japanese ancestry and their immigrant parents were imprisoned by the United States Government during the war.[4][5][6] Topaz has been referred to as a "War Relocation Center," "relocation camp," "relocation center," "internment camp," and "concentration camp," and the controversy over which term is the most accurate and appropriate continues to the present day.[7][8][9]

In 1998, use of "concentration camp" gained greater credibility prior to the opening of an exhibit about the American camps at Ellis Island. Initially, the American Jewish Committee (AJC) and the National Park Service, which manages Ellis Island, objected to the use of the term in the exhibit.[10] However, during a subsequent meeting held at the offices of the AJC in New York City, leaders representing Japanese Americans and Jewish Americans reached an understanding about the use of the term.[11] After the meeting, the Japanese American National Museum and the AJC issued a joint statement (which was included in the exhibit) that read in part:

A concentration camp is a place where people are imprisoned not because of any crimes they have committed, but simply because of who they are. Although many groups have been singled out for such persecution throughout history, the term 'concentration camp' was first used at the turn of the [20th] century in the Spanish American and Boer Wars. During World War II, America's concentration camps were clearly distinguishable from Nazi Germany's. Nazi camps were places of torture, barbarous medical experiments and summary executions; some were extermination centers with gas chambers. Six million Jews were slaughtered in the Holocaust. Many others, including Gypsies, Poles, homosexuals and political dissidents were also victims of the Nazi concentration camps. In recent years, concentration camps have existed in the former Soviet Union, Cambodia and Bosnia. Despite differences, all had one thing in common: the people in power removed a minority group from the general population and the rest of society let it happen.[12][13]

The New York Times published an unsigned editorial supporting the use of "concentration camp" in the exhibit.[14] An article quoted Jonathan Mark, a columnist for The Jewish Week, who wrote, "Can no one else speak of slavery, gas, trains, camps? It's Jewish malpractice to monopolize pain and minimize victims."[15] AJC Executive Director David A. Harris stated during the controversy, "...We have not claimed Jewish exclusivity for the term 'concentration camps.'"[16]

History of Topaz

Following American entry into World War II, approximately 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent and Japanese-born residents of the West Coast of the United States were forced to leave their homes in California, Oregon and Washington as a result of Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin Roosevelt.

About 10,000 left the off-limits area during the "voluntary evacuation" period, and avoided internment.

The remaining 110,000 were soon removed from their homes by Army and National Guard troops. First housed in places such as racetrack stables, eventually they were moved to various camps, hundreds or even thousands of miles from home.

Topaz was the primary internment site in the state of Utah. A smaller camp existed briefly at Dalton Wells, a few miles North of Moab, which was used to isolate a few men considered to be troublemakers prior to their being sent to Leupp, Arizona. A site at Antelope Springs, in the mountains west of Topaz, was used as a recreation area by the residents and staff of Topaz.[17]

Topaz was originally known as the Central Utah Relocation Center, but this name was abandoned when administrators realized that the acronym was naturally pronounced "Curse." The camp was then briefly named for the closest settlement, until nearby Mormon residents (with their own heritage of forced relocation) demanded that their town name not be associated with a "prison for the innocent." The final name, Topaz, came from a mountain which overlooks the camp from 9 miles (14.5 km) away.[18]

Utah governor Herbert B. Maw opposed the relocation of any Japanese Americans into the state, stating that if they were such a danger to the West Coast, they would be a danger to Utah[19] (the only governor who did not oppose bringing the Japanese Americans to his state was Colorado governor Ralph Carr).

Topaz was opened September 11, 1942, and eventually became the fifth-largest city in Utah, with over 9,000 internees and staff, and covering approximately 31 square miles (80.3 km2) (mostly used for agriculture).[18] It was closed on October 31, 1945.

The camp was governed by Charles F. Ernst until June 1944, when the position was taken over by Luther T. Hoffman following Ernst's resignation.[20]

Life at Topaz

Climate

Surrounded by desert, Topaz was an entirely new environment for internees, most of whom had been rounded up in the San Francisco area. Located at 4,580 feet (1,396.0 m) above sea level in the Sevier Desert, the high desert environment, classified as BWk under the Köppen classification could be harsh at times. In the arid environment, temperatures could vary greatly throughout the day. The area also experienced powerful winds and dust storms. One such storm caused structural damage to 75 buildings in 1944. Winters were cold, with averages below freezing for several months and an average of 18 inches of snow received. Spring rains turned the clay soil to mud, which bred mosquitoes.[21] Summers were hot, with occasional thunderstorms and temperatures that could exceed 100 degrees F. In 1942, the first snowfall occurred on October 13, before camp construction was fully complete.[22]

Architecture and Living Arrangements

Topaz contained a living complex known as the "city", about one mile square, as well as extensive agricultural lands. Within the city, forty-two blocks were reserved for internees, thirty-four of which were residential. Each block housed 200-300 people, housed in barracks that held five people within a single 20x20ft room. Families were generally housed together, while single adults would be housed with four other unrelated individuals. Residential blocks also contained a recreation hall, a mess hall, an office for the block manager, and a combined laundry/toilet/bathing facility. Each block contained only four bathtubs for all the women and four showers for all the men living there. These packed conditions often resulted in little privacy for residents.[23]

Barracks were build out of wood frame covered in tarpaper, with wooden floors. The barracks were eventually lined with sheetrock, and the floors filled with masonite, but not until many internees had already moved in to the camp, experiencing conditions that let in the wind. While the construction began in July 1942,[23] the first inmates moved in in September 1942, and the camp was not completed until early 1943. Camp construction was completed in part by 214 interned volunteers.[24] Rooms were heated by pot-bellied stoves. Inmates built their own furniture, including beds, tables, and cabinets, from scrap wood leftover from the construction of the camp. Some families also modified their living quarters with fabric partitions.[25]

Topaz also included a number of communal areas, including a high school, two elementary schools, a 28-bed hospital, at least two churches, and a community garden, among others. There was a cemetery as well, although it was never used- all 144 people who died in the camp were cremated and their ashes were held for burial until after the war.[23] Although Yoshiko Uchida reported that there were several burials, it is believed that she was remembering funeral services as being followed by burial.

The camp was patrolled by 85-150 soldiers, and was surrounded by a barbed wire fence. Manned watchtowers with searchlights were placed every quarter of a mile surrounding the perimeter of the camp.

Camp Politics

In 1943, all adult internees were issued a loyalty questionnaire asking them to for willingness to fight in the US Armed Forces and to swear allegiance to the United States and renounce loyalty to the Emperor of Japan. Many Japanese-born Issei, who were barred from attaining American citizenship, resented the second question, feeling that an affirmative answer would leave them effectively stateless. Others objected on other political grounds. In Topaz, nearly 20% of male residents answered in the negative. Anger was high, and was expressed through a few scattered assaults against inmates perceived as too close to the administration. Eventually, a re-wording of the questions soothed tensions.[23]

Related to the pledge, men throughout the camps were permitted to prove their loyalty by serving in the war. A number of young men from Topaz joined with their counterparts from other camps to sign up in the Army to fight in Europe with the highly decorated 442nd Regimental Combat Team. 451 residents from Topaz served in the U.S. military and 15 were killed in action.[24]

._-_NARA_-_538191.jpg)

The death of 63-year-old James Wakasa, who was shot to death on April 11, 1943 by guards for wandering too close to the camp boundary, caused tensions to rise in the camp. Internees reacted with massive work stoppages protesting the death and the surrounding secrecy. In response, the administration determined that fears of subversive activity at the camp were largely without basis, and significantly relaxed security.[24] Internees were able to get permission to leave the camp for hiking and even employment in nearby Delta, but Topaz was still a concentration camp, with residents subject to the control of the War Relocation Authority.

Topaz internees Fred Korematsu and Mitsue Endo challenged their internment in court. Korematsu's case was heard and rejected at the US Supreme Court (Korematsu v. United States), the largest case to challenge internment, while Endo's case was upheld.[26]

Daily Life

Most internees arrived at the camp from Tanforan or Santa Anita Park holding centers; the majority hailed from the San Francisco Bay Area. 65% were Nisei or Kibei- American-born citizens.[23]

The camp was designed to be self-sufficient, and the majority of land within the camp was devoted to farming. Topaz inmates raised cattle, pigs, and chickens in addition to feed crops and vegetables. Due to harsh weather, poor soil, and short growing conditions, the camp was not able to supply all of its animal feed, but camp produce won awards at the Millard County Fair.[27]

Topaz contained two elementary schools, Desert View Elementary and Mountain View Elementary, Topaz High School (grades 7-12) and an adult education program. The schools were taught by a combination of local teachers and internees. Topaz High School developed a devoted community, with reunions held up to 40 years after internment. Sports were popular within the schools as well as the adult population, with sports including baseball, basketball, and sumo wrestling popularly practiced.[28] The Topaz High School sports teams were known as the "Rams."

Cultural associations sprung up throughout the camp. Topaz had a newspaper, the Topaz Times, a literary publication called Trek, and two libraries which eventually contained 7,000 items in both English and Japanese. Artist Chiura Obata led the Tanforan Art School at Topaz, offering art instruction to over 600 students.[24] Internees in all of the camps left their mark on many of the improvements made during their imprisonment. Names, comments and even poetry were impressed into drying concrete in a number of projects, some in English and others in Japanese. These can be seen today, though visitors must search for them on their own.

Some internees were permitted to leave the camp to find employment. In 1943 over 500 internees obtained seasonal agricultural work outside the camp, with another 130 working in other fields outside the camp.[29] Utah faced an agricultural labor shortage at the time, and polling showed that a majority of Utahns supported this policy.[30]

Internees were also sometimes permitted to leave the camp for recreation. A former Civilian Conservation Corps camp at Antelope Springs, in mountains 90 miles (144.8 km) to the west, was taken over as a recreation area for internees and camp staff, and two buildings from Antelope Springs were brought to the central area to be used as Buddhist and Christian churches.[21] The airstrip at Antelope Springs was used by liaison planes which flew some camp administrators for brief trips to the mountains. Internees and most staff had to endure a three-hour truck trip each way.

Notable Topaz internees

- Karl Ichiro Akiya (1909–2001), a writer and political activist.

- Richard Aoki (1938–2009), an American civil rights activist.

- Hisako Shimizu Hibi (1907–1991), an Issei painter and printmaker.

- Yuji Ichioka (1936–2002), an American historian who coined the term "Asian American".

- George Ishiyama (1914–2003), a Japanese American businessman and former president of Alaska Pulp Corporation. Also interned at Heart Mountain.

- Tsuyako Kitashima (1918–2006), a Japanese American activist noted for her role in seeking reparations for Japanese American internment.

- Fred Korematsu (1919–2005), who challenged the constitutionality of Executive Order 9066 in Korematsu v. United States.

- Toshio Mori (1910–1980), author.

- Robert Murase (1938–2005), a world-renowned landscape architect.

- Chiura Obata (1885–1975), a Japanese American artist.

- Frank H. Ogawa (1917–1994), the first Japanese American to serve on the Oakland City Council.

- Miné Okubo (1912–2001), a Japanese American artist and writer, noted for her book, Citizen 13660.

- Mary Yamashiro Otani (1923–2005), a community activist.

- Kay Sekimachi (born 1926), an American fiber artist.

- Toyo Suyemoto (1916-2013), an American poet, memoirist, and librarian

- Goro Suzuki (1917–1979), the Oakland-born entertainer remembered by millions under his stage name, Jack Soo, star of the original stage and movie productions of Flower Drum Song and remembered for his role as Detective Nick Yemana on the 1970s sitcom Barney Miller. Suzuki was a favorite performer at Topaz gatherings.

- Dave Tatsuno (1913–2006), a Japanese American businessman who documented life in an American concentration camp on film.[31]

- Kazue Togasaki (1897-1992), one of the first two women of Japanese ancestry to earn a medical degree in the United States. Also interned at Tule Lake and Manzanar.

- Yoshiko Uchida (1921–1992), a Japanese American writer, most notable for her books, Desert Exile: The Uprooting of a Japanese American Family[32] and Picture Bride.[33]

- Thomas Yamamoto (1917–2004), an American artist.

Topaz in film

Topaz War Relocation Center is the setting for the film American Pastime, a dramatization based on actual events, which tells the story of Nikkei baseball in the camps. A portion of the camp was duplicated for location shooting in Utah's Skull Valley, approximately 40 miles (64.4 km) west of Salt Lake City and 75 miles (120.7 km) north of the actual Topaz site. The film was released in May 2007.

Documentaries about the Topaz War Relocation Center include Dave Tatsuno's Topaz and Ken Verdoia's 1987 work of the same name.[34]

Dave Tatsuno (1913–2006), had a movie camera smuggled into the camp, at the urging of his supervisor, Walter Honderick.[31] Film which he shot from 1943 to 1945 became the documentary Topaz. This film was deemed "culturally significant" by the United States Library of Congress in 1997, and was the second film to be selected for preservation in the National Film Registry (behind the "Zapruder" film of the JFK assassination). Until his death, Tatsuno was an Emeritus member of the board of the Topaz Museum, which is working to preserve the site.

Topaz in literature

Yoshiko Uchida's young adult novel Journey to Topaz recounts the story of Yuki, a young Japanese American girl, whose world is disrupted when, shortly after Pearl Harbor, she and her family must leave their comfortable home in the Berkeley suburbs for the dusty barracks of Topaz. The book is largely based on Uchida's personal experiences: she and her family were interned at Topaz for three years. Julie Otsuka's Novel "When The Emperor Was Divine" tells the story of a family forced to relocate from Berkeley, CA to Topaz in September 1942. The minimalist novel confronts the issues of freedom, loyalty, and identity for the Japanese American Family during World War II. The characters must adjust from their comfortable life in California to the uncertainty of the camps and then return to a town that is not what it once was.

Topaz in recent years

After Topaz was closed, the land was sold and most of the buildings were auctioned off and removed from the site. Even the pipes used to provide water to the camp were sold, and the trenches remain following their removal years ago.

Many of the buildings from the camp still stand, used as farm buildings throughout central Utah, and an alert observer will see several of them during the drive to and from the central area site. Generally in disrepair, a few are well-maintained by their current owners and used for storage or as seasonal apartments for migrant workers.

The remains of the central living area, approximately one square mile, are located southwest of the intersection of 10000 West and 4500 North streets, in Millard County. One of the barracks has been moved to Delta, where it now sits behind the Great Basin Museum. Most of the central area now belongs to the Topaz Museum. Other portions are still used as residential sites.

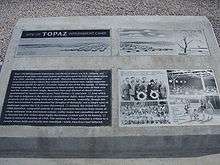

In 1976, the year of the United States' Bicentennial, a monument was placed on the northwestern corner of the central area. Having been vandalized several times, it was eventually replaced in 2002 by another monument of more modern design.

Other areas of significance within the camp's outer boundaries include turkey and hog farms, a cattle ranch and farmlands, all built on land which was bare and unused when the internees arrived. Today, these sites belong to various private owners, a number of whom have made plans to transfer the properties to Topaz Museum.

Numerous foundations, concrete-lined excavations and other ground-level features can be seen at the various sites, but few buildings remain, and natural vegetation has taken over most of the abandoned areas.

The runway at Antelope Springs was rendered unusable by numerous trenches which were dug across it to prevent its use for illicit purposes.

On March 29, 2007, United States Secretary of the Interior Dirk Kempthorne designated "Central Utah Relocation Center Site" a National Historic Landmark.[35]

Meteorite found near Topaz

While interned at Topaz during World War II, Akio Uhihera and Yoshio Nishimoto were on a rock hunting expedition in the Drum Mountains, 16 miles west of the concentration camp. Akio noticed an interesting rock near a sagebrush, and after some excavation found that it was a 1,164 pound rare iron meteorite. What is left of the meteorite is now on display at the Smithsonian Institution.[36]

Remembrance

.jpg)

The Topaz Museum (55 West Main, Delta, Utah) works to preserve important sites at Topaz, and to provide information to those interested in the history of the camps.

The Topaz Museum's mission statement reads:

To preserve the Topaz site and the history of the internment experience during World War II; to interpret its impact on the internees, their families, and the citizens of Millard County; and to educate the public in order to prevent a recurrence of a similar denial of American civil rights.[37]

Statistics

- Camp opened: September 11, 1942 (first internees arrived)

- Camp closed: October 31, 1945 (last internees left)

- Total number interned: 11,212

- Peak number of internees: 8,316

- Internee deaths at Topaz: 130 by natural causes, 1 killed by gunfire

- Nisei who joined United States Army while interned at Topaz: 451 (80 volunteers, 371 drafted)

- Killed In Action: 15

See also

- Japanese American Internment

- Other camps:

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 "Central Utah Relocation Center (Topaz) Site". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-06-12.

- ↑ Farrell, Mary M.; Lord, Florence B.; Lord, Richard W.; Burton, Jeffery F. (2002). Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites. University of Washington Press. p. 259. ISBN 0-295-98156-3.

- ↑ "The Manzanar Controversy". Public Broadcasting System. Retrieved July 18, 2007.

- ↑ Daniels, Roger (May 2002). "Incarceration of the Japanese Americans: A Sixty-Year Perspective". The History Teacher. 35 (3): 4–6. doi:10.2307/3054440. Retrieved 2007-07-18.

- ↑ Ito, Robert (1998-09-15). "Concentration Camp Or Summer Camp?". Mother Jones. Retrieved 2007-07-19.

- ↑ Manzanar Committee (1998). Reflections: Three Self-Guided Tours Of Manzanar. Manzanar Committee. iii–iv. ISBN 0-15-669261-9.

- ↑ "CLPEF Resolution Regarding Terminology". Civil Liberties Public Education Fund. 1996. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

- ↑ "Densho: Terminology & Glossary: A Note On Terminology". Densho. 1997. Retrieved July 15, 2007.

- ↑ Sengupta, Somini (1998-03-08). "What Is a Concentration Camp? Ellis Island Exhibit Prompts a Debate". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ↑ McCarthy, Sheryl (July–August 1999). "Suffering Isn't One Group's Exclusive Privilege". HumanQuest. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ↑ "American Jewish Committee, Japanese American National Museum Issue Joint Statement About Ellis Island Exhibit Set To Open April 3" (Press release). Japanese American National Museum and American Jewish Committee. 1998-03-13. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ↑ Sengupta, Somini (1998-03-10). "Accord On Term "Concentration Camp"". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ↑ "Words for Suffering". New York Times. 1998-03-10. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ↑ Haberman, Clyde (1998-03-13). "NYC; Defending Jews' Lexicon Of Anguish". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ↑ Harris, David A (1998-03-13). "Exhibition on Camps". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ↑ "Antelope Springs (detention facility)". Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- 1 2 "Topaz". Densho Encyclopedia. Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ↑ Arrington, Leonard J. (1997). The Price of Prejudice: the Japanese-American Relocation Center in Utah During WWII (2nd ed.). Delta, Utah: Topaz Museum. p. 15. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ↑ Arrington, Leonard J. (1997). The Price of Prejudice: the Japanese-American Relocation Center in Utah During WWII (2nd ed.). Delta, Utah: Topaz Museum. p. 25. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- 1 2 Lillquist, Karl (September 2007). Imprisoned in the Desert: The Geography of WWII-Era Japanese America Relocation Centers in the Western United States. Chapter 7: Central Washinton University. p. 274. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ↑ Beckwith, Jane. "Topaz Relocation Center". Utah History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Arrington, Leonard J. (1997). The Price of Prejudice: the Japanese-American Relocation Center in Utah During WWII (2nd ed.). Delta, Utah: Topaz Museum. p. 23. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Huefner, Michael. "Densho Encyclopedia: Topaz". encyclopedia.densho.org. Densho. Retrieved 2016-07-21.

- ↑ "Norman Hirose describes his family's living quarters in Topaz.". Densho Encyclopedia. Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ↑ Niiya, Brian. "Ex parte Endo". Densho Encyclopedia. Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ↑ Lillquist, Karl (September 2007). Imprisoned in the Desert: The Geography of WWII-Era Japanese America Relocation Centers in the Western United States. Chapter 7: Central Washinton University. p. 298. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ↑ Lillquist, Karl (September 2007). Imprisoned in the Desert: The Geography of WWII-Era Japanese America Relocation Centers in the Western United States. Chapter 7: Central Washinton University. p. 303. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ↑ Arrington, Leonard J. (1997). The Price of Prejudice: the Japanese-American Relocation Center in Utah During WWII (2nd ed.). Delta, Utah: Topaz Museum. p. 30. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ↑ Lillquist, Karl (September 2007). Imprisoned in the Desert: The Geography of WWII-Era Japanese America Relocation Centers in the Western United States. Chapter 7: Central Washinton University. p. 284. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- 1 2 Fox, Margalit (2006-02-13). "Dave Tatsuno, 92, Whose Home Movies Captured History, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- ↑ Uchida, Yoshiko (1982). Desert Exile: The Uprooting of a Japanese American Family. University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-96190-2.

- ↑ Uchida, Yoshiko (1987). Picture Bride. Simon & Schuster, Inc. ISBN 0-671-66874-9.

- ↑ Niiya, Brian (1987). "Topaz (film)". Densho.

- ↑ Lee, Toni and, Wolfe, Shane (2007-04-04). "Interior Secretary Kempthorne Designates 12 National Historic Landmarks in 10 States" (Press release). National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- ↑ Stokey, Kathleen (December 20, 1944), "Meteor Found in Utah: Japs Find Half-ton Specimen Near Topaz", Deseret News

- ↑ "Topaz Museum Mission Statement". Retrieved 2016-07-11.

Additional reading

- Arrington, Leonard J. (1997) [1962], The Price of Prejudice: the Japanese-American Relocation Center in Utah During WWII (with photographs and update, 2nd ed.), Delta, Utah: Topaz Museum, OCLC 38875423

- Beckwith, Jane (1994), "Topaz Relocation Center", in Powell, Allan Kent, Utah History Encyclopedia, Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah Press, ISBN 0874804256, OCLC 30473917

- Burton, Jeffery F.; Farrell, Mary; Lord, Florence; Lord, Richard (1999), "Chapter 12: Topaz Relocation Center", Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites, Publications in Anthropology, 74, Tucson, Arizona: Western Archaeological and Conservation Center, OCLC 43505944

- Okubo, Miné (1946), Citizen 13660, New York: Columbia University Press, OCLC 1309894

- Taylor, Sandra C. (1993), Jewel of the Desert: Japanese American Internment at Topaz, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0520080041, OCLC 26364261

- "Journey to Topaz" novel for children by Yoshiko Uchida, Grade 4 and up.

- "Journey Home" sequel to "Journey to Topaz."

- Huefner, Michael. "Densho Encyclopedia: Topaz". encyclopedia.densho.org. Densho. Retrieved 2016-07-21.

- Wakida, Patricia. "Densho Encyclopedia: Topaz Times (newspaper)". encyclopedia.densho.org. Densho. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Topaz War Relocation Center. |

Coordinates: 39°24′40″N 112°46′20″W / 39.41111°N 112.77222°W