Transliteration of Chinese

The different varieties of Chinese have been transcribed into many other writing systems.

General Chinese

General Chinese is a diaphonemic orthography invented by Yuen Ren Chao to represent the pronunciations of all major varieties of Chinese simultaneously. It is "the most complete genuine Chinese diasystem yet published". It can also be used for the Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese pronunciations of Chinese characters, and challenges the claim that Chinese characters are required for interdialectal communication in written Chinese.

General Chinese is not specifically a romanisation system, but two alternative systems. One uses Chinese characters phonetically, as a syllabary of 2082 glyphs, and the other is an alphabetic romanisation system with similar sound values and tone spellings to Gwoyeu Romatzyh.

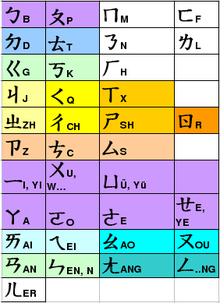

Bopomofo

Wu Jingheng (who had developed a "beansprout alphabet") and Wang Zhao (王照) (who had developed a Mandarin alphabet, Guanhua Zimu, in 1900)[1] and Lu Zhuangzhang were part of the Commission on the Unification of Pronunciation (1912–1913), which developed the rudimentary Jiyin Zimu (記音字母) system of Zhang Binglin into the Mandarin-specific phonetic system now known as Zhuyin Fuhao or Bopomofo, which was eventually proclaimed on 23 November 1918.

The significant feature of Bopomofo is that it is composed entirely of "ruby characters" which can be written beside any Chinese text whether written vertically, right-to-left, or left-to-right.[2] The characters within the Bopomofo system are unique phonetic characters, and are not part of the Latin alphabet. In this way, it is not technically a form of romanisation, but because it is used for phonetic transcription the alphabet is often grouped with the romanisation systems.

Taiwanese kana

Taiwanese kana is a katakana-based writing system once used to write Holo Taiwanese, when Taiwan was ruled by Japan. It functioned as a phonetic guide to Chinese characters, much like furigana in Japanese or Bopomofo. There were similar systems for other languages in Taiwan as well, including Hakka and Formosan languages.

Phags-pa script

The Phags-pa script was an alphabet designed by the Tibetan Lama Zhogoin Qoigyai Pagba (Drogön Chögyal Phagpa) for Yuan emperor Kublai Khan, as a unified script for the literary languages of the Yuan Dynasty. The Phags-pa script has helped reconstruct the pronunciation of pre-modern forms of Chinese but it totally ignores tone.

Manchu alphabet

The Manchu alphabet was used to write Chinese in the Qing dynasty.

Mongolian alphabet

In Inner Mongolia the Mongolian alphabet is used to transliterate Chinese.

Xiao'erjing

Xiao'erjing is a system for transcribing Chinese using the Arabic alphabet. It is used on occasion by many ethnic minorities who adhere to the Islamic faith in China (mostly the Hui, but also the Dongxiang, and the Salar), and formerly by their Dungan descendants in Central Asia. Soviet writing reforms forced the Dungan to replace Xiao'erjing with a Roman alphabet and later a Cyrillic alphabet, which they continue to use up until today.

Romanisation

There have been many systems of romanisation throughout history. However, Hanyu Pinyin has become the international standard since 1982. Other well-known systems include Wade-Giles and Yale.

Cyrillisation

The Russian system for Cyrillisation of Chinese is the Palladius system. The Dungan language (a variety of Mandarin used by the Dungan people) was once written in the Latin script but now employs Cyrillic.

Other Cyrillic using countries other than Russia use different systems.

Braille

A number of braille transcriptions have been developed for Chinese. In mainland China, traditional Mainland Chinese Braille and Two-Cell Chinese Braille are used in parallel to transcribe Standard Chinese. Taiwanese Braille is used in Taiwan for Taiwanese Mandarin.[3]

In traditional Mainland Chinese Braille, consonants and basic finals conform to international braille, but additional finals form a semi-syllabary, as in bopomofo. Each syllable is written with up to three Braille cells, representing the initial, final and tone, respectively. In practice tone is generally omitted.

In Two-Cell Chinese Braille, designed in the 1970s, each syllable is rendered with two braille characters. The first combines the initial and medial; the second the rhyme and tone. The base letters represent the initial and rhyme; these are modified with diacritics for the medial and tone.

Like traditional Mainland Chinese Braille, Taiwanese Braille is a semi-syllabary. Although based marginally on international braille, the majority of consonants have been reassigned.[4]

See also

References

- ↑ Hsia, T., China’s Language Reforms, Far Eastern Publications, Yale University, (New Haven), 1956. pg. 108

- ↑ This is why Bopomofo is popular where Chinese characters are still written vertically, right-to-left, or left-to-right, such as in Taiwan.

- ↑ Not for Taiwanese Hokkien, which commonly goes by the name "Taiwanese"

- ↑ Only p m d n g c a e ê ü (from p m d n k j ä è dropped-e ü) approximate the French norm. Other letters have been reassigned so that the sets of letters in groups such as d t n l and g k h are similar in shape.