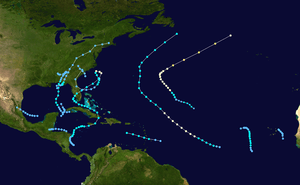

Tropical Storm Alberto (1994)

| Tropical storm (SSHWS/NWS) | |

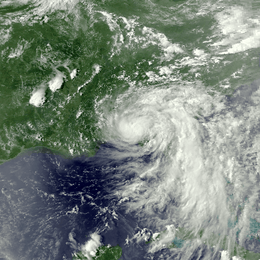

Satellite image of Alberto near landfall | |

| Formed | June 30, 1994 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | July 7, 1994 |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 65 mph (100 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 993 mbar (hPa); 29.32 inHg |

| Fatalities | 32 direct |

| Damage | $1 billion (1994 USD) |

| Areas affected | Florida Panhandle, Alabama, Georgia |

| Part of the 1994 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Tropical Storm Alberto was the costliest storm of the 1994 Atlantic hurricane season. The storm was the first named storm of the season. It hit Florida across the Southeast United States in July, causing a massive flooding disaster while stalling over Georgia and Alabama. Alberto caused $1 billion in damage (1994 USD) and 30 deaths.

Meteorological history

A tropical wave moved off the coast of Africa on June 18. It moved westward across the dry, shear-ridden Atlantic Ocean, and remained weak until passing through the Greater Antilles. Deep convection developed over the wave in response to light vertical shear and warm waters of the Caribbean Sea, and organized into Tropical Depression One near the Isle of Youth on June 30. A trough of low pressure brought the depression to the northwest over the Gulf of Mexico, remaining weak due to increased upper level shear. The shear abated, allowing the depression to strengthen into Tropical Storm Alberto on July 2.

Alberto continued to the north-northeast in response to a short wave trough, and steadily strengthened as the convection became embedded around the center. Tropical Storm Alberto peaked with maximum sustained winds of 65 miles per hour (105 km/h) just as it was making landfall near Destin, Florida. The storm would have likely attained hurricane status had it been over water just hours longer, as a warm spot was apparent, indicating the formation of an eye feature. Alberto quickly weakened to a tropical depression over Alabama as it continued to the northeast, but retained a well-organized circulation. High pressures build to its north and east, causing the remnant tropical depression to stall over northwestern Georgia. It turned to a west drift, and dissipated over central Alabama on July 7.

Preparations

On June 30, on the day of Alberto's formation, a tropical storm warning was issued from Puerto Juárez to Mérida, Mexico; the warning was discontinued on July 1. In the United States, a tropical storm watch was posted on July 2 for locations between Sabine Pass, Texas and Pensacola, Florida. The watch was subsequently upgraded to a tropical storm warning from Gulfport, Mississippi to Cedar Key, Florida; it was soon altered to a hurricane warning. Later on July 3, the hurricane warning was discontinued and replaced with a tropical storm warning, which was lifted at 2100 UTC.[1]

On the Florida Panhandle, residents boarded up windows in anticipation of what was to be a "fury".[2] At gasoline stations, unusually long lines formed, and local stores did increased business in selling emergency supplies.[3] Thousands of tourists along the coast left the region; a local deputy was quoted as estimating that 10,000 people checked out of their hotels early. On Okaloosa Island and Holiday Isle, ground-floor house and businesses were forced to evacuate.[4] Civil-defense authorities evacuated residents from low-lying locations.[5] Then-Governor of Florida, Lawton Chiles, declared a State of emergency for parts of the state, and advised residents along the coast to monitor updates regarding the storm.[6] Over 3,000 people sought refuge in Red Cross shelters along the coast of Florida, westward into parts of Alabama.[7]

Impact

Upon forming, the storm dropped heavy rainfall over parts of Cuba, peaking at 10 inches (250 mm).[8][9]

Florida

At Destin, Florida, sustained winds blew at 63 miles per hour (101 km/h),[10] while winds gusted to 75 miles per hour (121 km/h); however, there was an unofficial report of 89 miles per hour (143 km/h) gusts. There, barometric pressure fell to 993 mb in association with Alberto. Storm tides of 5 feet (1.5 m) was estimated along the coast of Destin, while tides reached 3 feet (0.91 m) at Panama City.[8] At St. George Island, wind gusts reached 58 miles per hour (93 km/h). Beach erosion and tidal flooding occurred along the coast.[11] Throughout northwest Florida, 5 inches (130 mm) of rain fell,[8] with totals as high as 21.57 inches (548 mm). Other precipitation accumulations include 13.25 inches (337 mm) at Caryville.[12]

Along the coast, damage was limited to sea walls, piers and boats, and roof damage to some beachfront motels. As the storm progressed inland, it brought down signs, billboards, trees and powerlines, and triggered moderate flooding; about 18,500 customers lost electric power. As a weakened tropical depression, the remnants of Alberto dropped extensive rainfall throughout the region.[10] As heavy rain fell to the north, tremendous volumes of water moved down major river systems into the Florida Panhandle.[13] As a result, there was extensive river flooding that exceeded 100-year events in some locations, particularly along the Apalachicola and Chipola Rivers. The Apalachicola remained above flood stage until August, although in localized areas, flooding persisted until September due to Tropical Storm Beryl. A total of 300,000 chickens and 125 cattles and hogs were lost within the state, and offshore, 90% of the oysters in Apalachicola Bay were lost. The flooding was severe, inflicting $40 million (1994 USD) in damage to infrastructure, $14 million in insured damage, and $25 million in agricultural losses.[10]

Georgia

In Georgia, rainfall from the tropical cyclone peaked at 27.85 in (707 mm) near Americus.[14] Due to a previously stalled cold front, which subsequently caused Alberto to remain stationary, the ground was already saturated with rainfall. Virtually all of the precipitation became instant runoff into streams and rivers.[15] Peak discharges along the Flint and Ocmulgee rivers exceeded 100-year flood levels.[16] At least 100 dam and recreational watersheds suffered severe damage or were destroyed. Many roads were inundated, forcing the closure of 175 roads and 1,000 bridges.[16][17] Damage to highway infrastructure exceeded $130 million.[16]

Approximately 471,000 acres (191,000 ha) of croplands were submerged, causing about $100 million in damage to agriculture. Fifteen of the United States Geological Survey's (USGS) gaging stations were severely damaged or demolished, forcing data to be collected manually and reported by cellphone. Due to flooded water system, approximately 500,000 people were temporarily left without drinking water. There were 31 deaths in the state,[16] most of which from cars being swept onto flooded roads or into swollen creeks.[17] With $750 million in damage, Alberto was considered the costliest tropical cyclone in Georgia,[18] while the flooding was considered the worst in the history of the state.[19]

Southwest Georgia

Along the state line with Florida, five counties in southwestern Georgia reported 3 to 5 in (76 to 127 mm) of precipitation. In Bainbridge, the rising Flint River caused 300 residents to evacuate. A local fertilizer plant was also threatened by the swollen Flint River. In the five counties of Brooks, Colquitt, Cook, Thomas, and Worth, the Little and Ochlockonee rivers overflowed their banks, flooding adjacent areas. In Early and Miller counties, 7 to 10 in (180 to 250 mm) of rain fell between July 3 and July 7, while an additional 3 to 7 in (76 to 178 mm) of precipitation was observed from July 10 to July 14. Many low-lying areas were flooded. Seven families were evacuated from their homes in Safford due to flooding. Further north, the Flint River also overflow its banks in Baker and Mitchell. Extensive flooding occurred in Newton, with more than $100,000 in property damage. Widespread inundation of crops were reported in both counties.[15]

In Dougherty County, the Flint River exceeded its banks, forcing over 20,000 residents to evacuate. Five deaths were reported in the county, with four people drowning in the river and another from a woman being trapped in her home for several days. Several locations along State Route 37 flooded in Fort Gaines, a city in Clay County. To the north in Randolph County, Cuthbert recorded 23.85 in (606 mm) of rainfall during a 5-day period. Many streets in the city were flooded, including two portions of U.S. Route 82 and a part of State Route 266. In Terrell County, the sheriff's department reported that many roads were inundated due to swollen creeks and streams. A number of homes and businesses were suffered extensive impact, with up to several million dollars in many. A woman died in Dawson after her car was swept off the road into Chickasawhatchee River.[15]

Numerous county roads were flooded in Lee County due to swollen streams and creeks. Over 600 people were evacuated from their homes county-wide after rising waters began to flood residential areas. In Webster County, many roads were inundated due to the flooding of streams and creeks. About 1 to 5 in (25 to 127 mm) of precipitation fell in Dodge, Pulaski, Wilcox counties, inundating croplands along the Ocmulgee River. Extensive flooding was reported in much of Dooly County. Several bridges washed out and many roads were closed, including State Route 27 near Drayton. Some residential areas were flooded, resulting in evacuations. In Crisp County, a portion of Interstate 75 was closed due to flooding. A subdivision was evacuated, as well as areas around Lake Blackshear.[15]

In Americus, flood waters threatened 21,000 acres (8,500 ha) of peanuts and other crops such as cotton and corn, while numerous streets, businesses, and homes were inundated. Nine people died after cars washed off of inundated roads. Two other fatalities occurred after flood waters destroyed a home on Lake Jackson and another after a mobile home was swept away. In Plains, 22.8 inches (580 mm) of rainfall was observed. Several homes and businesses were inundated. A tractor trailer on U.S. Route 280 washed away, killing the three male occupants of the vehicle.[15] Additionally, flood waters approached the home of former President of the United States Jimmy Carter, but no damage occurred.[20] Standing water also covered numerous roads in Leslie. On Lake Corinth, a 17‑year‑old boy attempted to fix a downed telephone line, but died after his boat capsized.[15]

Central Georgia

For a time, the city of Macon was completely cut off by flood waters severing all roads in and out of the city. Most of the city lost all water service during the height of flood when two major treatment plants were flooded. It took almost two weeks before service was restored. The city of Montezuma was the hardest hit of all when the flood levee was topped by the nearby Flint River. The entire downtown area was inundated with up to 18 feet of water. Cleanup would take months to complete.[15]

In Columbus, 3.5 in (89 mm) of precipitation was observed in 24 hours, while 5.72 in (145 mm) of rain fell throughout a 4-day period. Police reported that numerous streets were flooded, including a cave-in caused by runoff. Three homes in West Point were evacuated.[15]

Several people in Taylor County reported seeing a funnel cloud. Thunderstorm winds damaged some buildings and mobile homes. One woman suffered minor injuries.[15]

North Georgia

Heavy rainfall extended into northern Georgia. In Heard County, the city of Franklin recorded 6.13 in (156 mm) of precipitation. Portions of State Route 34 were inundated with up to 2 ft (0.61 m) of water. To the east in Coweta County, 6 to 8 in (150 to 200 mm) of rain fell. Two mobile home parks were flooded. Water also inundated Interstate 85 at exit 11. In Spalding County, 14.30 in (363 mm) of precipitation was observed at Griffin. Many homes and businesses were flooded and several earthen dams failed. A woman died when her cars ran into a washed out road; two others were injured in the same location.[15]

Flooding also occurred in portions of the Atlanta metropolitan area. About 9–13 in (230–330 mm) of rain fell in Butts County. Several roads were inundated by flood waters and a number of culverts and drainage systems that collapsed due to excessive water; a total of 20 roads were closed. Seventy to eighty families in the county were evacuated. At Indian Springs State Park, water overflowed the dams, flooding the park with up to 3 ft (0.91 m) of water.[15]

Rainfall totals between 4 and 7 in (100 and 180 mm) flooded numerous culverts, houses, and roads in Rockdale County. Additionally, a 16‑year‑old girl drowned after attempting to rescue a dog. At the Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport in Atlanta, 7.05 in (179 mm) of rain was recorded, forcing many to evacuate flooded apartments in nearby College Park.[15]

Another person died in a DeKalb County due to a car accident caused by slick roads.[21]

Aftermath

Because of the severe flooding in the state of Georgia, then-governor Zell Miller declared 30 counties in a state of emergency, which included the following counties in central Georgia: Bibb, Butts, Crawford, Dooly, Houston, Jones, Lamar, Macon, Monroe, Peach, Sumter, Taylor, Twiggs, and Upson.

See also

- Other storms of the same name

- List of wettest tropical cyclones in the United States

- List of floods

- List of Florida hurricanes (1975-1999)

- Timeline of the 1994 Atlantic hurricane season

References

- ↑ Edward Rappaport. "Tropical Storm Alberto Preliminary Report Page 10". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- ↑ Jason Vest (July 4, 1994). "Tropical Storm Alberto Not So Tough; As `Fury' Sputters, Only Tourism Is Hit Hard in Florida Panhandle". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- ↑ Staff Writer (July 3, 1994). "Florida Braces for Tropical Storm Alberto". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- ↑ Staff Writer (July 4, 1994). "Tropical Storm Hits Florida, but Damage Is Little". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- ↑ Staff Writer (July 3, 1994). "Season's 1st Tropical Storm Heads for Gulf Coast". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- ↑ Associated Press (July 3, 1994). "Storm Headed for Florida". The Victoria Advocate. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- ↑ Reuters (July 4, 1994). "First Tropical Storm Pounds Florida". The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- 1 2 3 Edward Rappaport. "Tropical Storm Alberto Preliminary Report Page 3". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ Associated Press (July 2, 1994). "A tropical depression that dumped up to 10". San Antonio Express-News. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- 1 2 3 "Flood Event Report for Florida". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ "High Wind Event Report for Florida". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ Edward Rappaport. "Tropical Storm Alberto Preliminary Report Page 10". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ National Weather Service. "Tropical Storm Alberto Floods of July 1994 Disaster Survey Report". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ Roth, David M. (April 29, 2015). "Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Data. United States Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Storm Data - July 1994" (PDF). National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Timothy C. Stamey (1995). Floods In Central And Southeastern Georgia In July 1994 (PDF) (Report). Atlanta, Georgia: Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- 1 2 Flood-Related Mortality -- Georgia, July 4-14, 1994 (Report). Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. July 29, 1994. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- ↑ Hurricanes in Georgia (Report). Atlanta, Georgia: Georgia Emergency Management Agency. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- ↑ Peter Applebome (July 12, 1994). "Flood Brings Danger Now, Worry Later For Georgia". Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- ↑ "Carter's house is 'high and dry'". Deseret News. Associated Press. July 7, 1994. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ↑ Mary Braswell (June 27, 2014). "Remembering the 31 lives lost during the Flood of 1994". The Albany Herald. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tropical Storm Alberto (1994). |