Turmeric

| Turmeric | |

|---|---|

_W_IMG_2440.jpg) | |

| Inflorescence of Curcuma longa | |

| |

| Processed turmeric | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Monocots |

| (unranked): | Commelinids |

| Order: | Zingiberales |

| Family: | Zingiberaceae |

| Genus: | Curcuma |

| Species: | C. longa |

| Binomial name | |

| Curcuma longa L.[1] | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Curcurma domestica Valeton | |

Turmeric or tumeric (Curcuma longa) /ˈtərmərɪk/ or /ˈtjuːmərɪk/ or /ˈtuːmərɪk/[2] is a rhizomatous herbaceous perennial plant of the ginger family, Zingiberaceae.[3] It is native to southern Asia, requiring temperatures between 20 and 30 °C (68 and 86 °F) and a considerable amount of annual rainfall to thrive.[4] Plants are gathered annually for their rhizomes and propagated from some of those rhizomes in the following season.

When not used fresh, the rhizomes are boiled for about 30–45 minutes and then dried in hot ovens, after which they are ground into a deep-orange-yellow powder[5] commonly used as a coloring in Bangladeshi cuisine, Indian cuisine, Iranian cuisine, Pakistani cuisine and curries, and for dyeing.

History and etymology

Turmeric has been used in Asia for thousands of years and is a major part of Siddha medicine.[6] It was first used as a dye, and then later for its medicinal properties.[7]

The origin of the name is uncertain, possibly deriving from Middle English/early modern English as turmeryte or tarmaret. There was speculation that it may be of Latin origin, terra merita (merited earth).[8]

The name of the genus, Curcuma, is from an Arabic name of both saffron and turmeric (see Crocus).

Botanical description

Appearance

Turmeric is a perennial herbaceous plant that reaches up to 1 m (3 ft 3 in) tall. Highly branched, yellow to orange, cylindrical, aromatic rhizomes are found. The leaves are alternate and arranged in two rows. They are divided into leaf sheath, petiole, and leaf blade.[9] From the leaf sheaths, a false stem is formed. The petiole is 50 to 115 cm (20 to 45 in) long. The simple leaf blades are usually 76 to 115 cm (30 to 45 in) long and rarely up to 230 cm (91 in). They have a width of 38 to 45 cm (15 to 18 in) and are oblong to elliptic, narrowing at the tip.

Inflorescence, flower, and fruit

In China, the flowering time is usually in August. Terminally on the false stem is a 12 to 20 cm (4.7 to 7.9 in) long inflorescence stem containing many flowers. The bracts are light green and ovate to oblong with a blunt upper end with a length of 3 to 5 cm.

At the top of the inflorescence, stem bracts are present on which no flowers occur; these are white to green and sometimes tinged reddish-purple and the upper ends are tapered.[10]

The hermaphrodite flowers are zygomorphic and threefold. The three 0.8 to 1.2 cm long sepals are fused, white, have fluffy hairs and the three calyx teeth are unequal. The three bright-yellow petals are fused into a corolla tube up to 3 cm long. The three corolla lobes have a length of 1.0 to 1.5 cm, and are triangular with soft-spiny upper ends. While the average corolla lobe is larger than the two lateral, only the median stamen of the inner circle is fertile. The dust bag is spurred at its base. All other stamens are converted to staminodes. The outer staminodes are shorter than the labellum. The labellum is yellowish, with a yellow ribbon in its center and it is obovate, with a length from 1.2 to 2.0 cm. Three carpels are under a constant, trilobed ovary adherent, which is sparsely hairy. The fruit capsule opens with three compartments.[11][12][13]

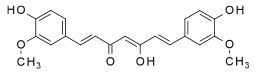

Biochemical composition

The most important chemical components of turmeric are a group of compounds called curcuminoids, which include curcumin (diferuloylmethane), demethoxycurcumin, and bisdemethoxycurcumin. The best-studied compound is curcumin, which constitutes 3.14% (on average) of powdered turmeric.[14] However, there are big variations in curcumin content in the different lines of the species Curcuma longa (1–3189 mg/100g). In addition, other important volatile oils include turmerone, atlantone, and zingiberene. Some general constituents are sugars, proteins, and resins.[15]

Uses

Culinary

Turmeric grows wild in the forests of South and Southeast Asia. It is one of the key ingredients in many Asian dishes. Indian traditional medicine, called Siddha, has recommended turmeric for medicine. Its use as a coloring agent is not of primary value in South Asian cuisine.

Turmeric is mostly used in savory dishes, but is used in some sweet dishes, such as the cake sfouf. In India, turmeric plant leaf is used to prepare special sweet dishes, patoleo, by layering rice flour and coconut-jaggery mixture on the leaf, then closing and steaming it in a special copper steamer (goa).

In recipes outside South Asia, turmeric is sometimes used as an agent to impart a golden yellow color. It is used in canned beverages, baked products, dairy products, ice cream, yogurt, yellow cakes, orange juice, biscuits, popcorn color, cereals, sauces, gelatins, etc. It is a significant ingredient in most commercial curry powders.

Most turmeric is used in the form of rhizome powder. In some regions (especially in Maharashtra, Goa, Konkan, and Kanara), turmeric leaves are used to wrap and cook food. Turmeric leaves are mainly used in this way in areas where turmeric is grown locally, since the leaves used are freshly picked. Turmeric leaves impart a distinctive flavor.

Although typically used in its dried, powdered form, turmeric is also used fresh, like ginger. It has numerous uses in East Asian recipes, such as pickle that contains large chunks of soft turmeric, made from fresh turmeric.

Turmeric is widely used as a spice in South Asian and Middle Eastern cooking. Many Persian dishes use turmeric as a starter ingredient. Various Iranian khoresh dishes are started using onions caramelized in oil and turmeric, followed by other ingredients. The Moroccan spice mix ras el hanout typically includes turmeric.

In India and Nepal, turmeric is widely grown and extensively used in many vegetable and meat dishes for its color; it is also used for its supposed value in traditional medicine.

In South Africa, turmeric is used to give boiled white rice a golden colour.

In Vietnamese cuisine, turmeric powder is used to color and enhance the flavors of certain dishes, such as bánh xèo, bánh khọt, and mi quang. The powder is used in many other Vietnamese stir-fried and soup dishes.

The staple Cambodian curry paste kroeung, used in many dishes including Amok, typically contains fresh turmeric.

In Indonesia, turmeric leaves are used for Minang or Padang curry base of Sumatra, such as rendang, sate padang, and many other varieties.

In Thailand, fresh turmeric rhizomes are widely used in many dishes, in particular in the southern Thai cuisine, such as the yellow curry and turmeric soup.

In medieval Europe, turmeric became known as Indian saffron because it was widely used as an alternative to the far more expensive saffron spice.[16]

Dye

Turmeric makes a poor fabric dye, as it is not very light fast, but is commonly used in Indian and Bangladeshi clothing, such as saris and Buddhist monks's robes.[17] Turmeric (coded as E100 when used as a food additive)[18] is used to protect food products from sunlight. The oleoresin is used for oil-containing products. A curcumin and polysorbate solution or curcumin powder dissolved in alcohol is used for water-containing products. Over-coloring, such as in pickles, relishes, and mustard, is sometimes used to compensate for fading.

In combination with annatto (E160b), turmeric has been used to color cheeses, yogurt, dry mixes, salad dressings, winter butter and margarine. Turmeric is also used to give a yellow color to some prepared mustards, canned chicken broths, and other foods (often as a much cheaper replacement for saffron).

Indicator

Turmeric paper, also called curcuma paper or in German literature Curcumapapier is paper steeped in a tincture of turmeric and allowed to dry. It is used in chemical analysis as an indicator for acidity and alkalinity.[19] The paper is yellow in acidic and neutral solutions and turns brown to reddish-brown in alkaline solutions, with transition between pH of 7.4 and 9.2.[20]

For pH detection, turmeric paper has been replaced in common use by litmus paper. Turmeric can be used as a substitute for phenolphthalein, as its color change pH range is similar.

Traditional uses

In Ayurvedic practices, turmeric has been used to treat a variety of internal disorders, such as indigestion, throat infections, common colds, or liver ailments, as well as topically to cleanse wounds or treat skin sores.[4]

Turmeric is considered auspicious and holy in India and has been used in various Hindu ceremonies for millennia. It remains popular in India for wedding and religious ceremonies.

Turmeric has played an important role in Hindu spiritualism. The robes of the Hindu monks were traditionally colored with a yellow dye made of turmeric. Because of its yellow-orange coloring, turmeric was associated with the sun or the Thirumal in the mythology of ancient Tamil religion. Yellow is the color of the solar plexus chakra which in traditional Tamil Siddha medicine is an energy center. Orange is the color of the sacral chakra.

The plant is used in Poosai (Tamil) to represent a form of the Tamil Goddess Kottravai. In Eastern India, the plant is used as one of the nine components of navapatrika along with young plantain or banana plant, taro leaves, barley (jayanti), wood apple (bilva), pomegranate (darimba), asoka, manaka or manakochu, and rice paddy. The Navaptrika worship is an important part of Durga festival rituals.[21]

It is used in poosai to make a form of Ganesha. Yaanaimugathaan, the remover of obstacles, is invoked at the beginning of almost any ceremony and a form of Yaanaimugathaan for this purpose is made by mixing turmeric with water and forming it into a cone-like shape.

Haldi ceremony (called Gaye holud in Bengal) (literally "yellow on the body") is a ceremony observed during Hindu wedding celebrations in many parts of India including Bengal, Punjab, Maharashtra and Gujarat. The 'ceremony takes place one or two days before the religious and legal Bengali wedding ceremonies. The turmeric paste is applied by friends to the bodies of the couple. This is said to soften the skin, but also colors them with the distinctive yellow hue that gives its name to this ceremony. It may be a joint event for the bride and groom's families, or it may consist of separate events for the bride's family and the groom's family.

During the Tamil festival Pongal, a whole turmeric plant with fresh rhizomes is offered as a thanksgiving offering to Suryan, the sun god. Also, the fresh plant sometimes is tied around the Pongal pot in which an offering of pongal is prepared.

In Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, as a part of the Tamil/Telugu marriage ritual, dried turmeric tuber tied with string is used to create a Thali necklace, the equivalent of marriage rings in western cultures. In western and coastal India, during weddings of the Marathi and Konkani people, Kannada Brahmins turmeric tubers are tied with strings by the couple to their wrists during a ceremony called Kankanabandhana.[22]

Friedrich Ratzel in The History of Mankind reported in 1896 that in Micronesia, the preparation of turmeric powder for embellishment of body, clothing, and utensils had ceremonial character.[23]

Adulteration

As turmeric and other spices are commonly sold by weight, the potential exists for powders of toxic, cheaper agents with a similar color to be added, such as lead(II,IV) oxide, giving turmeric an orange-red color instead of its native gold-yellow.[24] Another common adulterant in turmeric, metanil yellow (also known as acid yellow 36), is considered an illegal dye for use in foods by the British Food Standards Agency.[25]

Research

Basic research shows extracts from turmeric may have antifungal and antibacterial properties.[26]

Turmeric or its principal constituent, curcumin, has been studied in small clinical trials in many human diseases and conditions.[27][28][29]

See also

References

- ↑ "Curcuma longa information from NPGS/GRIN". ars-grin.gov. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- ↑ "Turmeric (pronunciation)". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 2015.

- ↑ Priyadarsini KI (2014). "The chemistry of curcumin: from extraction to therapeutic agent". Molecules. 19 (12): 20091–112. doi:10.3390/molecules191220091. PMID 25470276.

- 1 2 Prasad, S; Aggarwal, B. B.; Benzie, I. F. F.; Wachtel-Galor, S (2011). Benzie IFF, Wachtel-Galor S, eds. Turmeric, the Golden Spice: From Traditional Medicine to Modern Medicine; In: Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects; chap. 13. 2nd edition. CRC Press, Boca Raton (FL). PMID 22593922.

- ↑ "Turmeric processing". Kerala Agricultural University, Kerala, India. 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ Chattopadhyay, Ishita; Kaushik Biswas; Uday Bandyopadhyay; Ranajit K. Banerjee (10 July 2004). "Turmeric and curcumin: Biological actions and medicinal applications" (PDF). Current Science. Indian Academy of Sciences. 87 (1): 44–53. ISSN 0011-3891. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ↑ "Herbs at a Glance: Turmeric, Science & Safety". National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), National Institutes of Health. 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ↑ "Turmeric". Dictionary.com Unabridged Random House Dictionary. 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ↑ Curcuma longa A Modern Herbal, M Grieve. Accessed November 2013

- ↑ Curcuma longa Linn. Description from Flora of China, South China Botanical Garden. Accessed November 2013

- ↑ SIEWEK (2013) (in German), [, p. 72, at Google Books Exotische Gewürze Herkunft Verwendung Inhaltsstoffe], Springer-Verlag, pp. 72, ISBN 978-3-0348-5239-5, , p. 72, at Google Books

- ↑ "Kurkuma kaufen in Ihrem". Archived from the original on November 20, 2016. Retrieved November 20, 2016.

- ↑ Rudolf Hänsel, Konstantin Keller, Horst Rimpler, Gerhard Schneider (2013) (in German), [, p. 1085, at Google Books Drogen A-D], Springer-Verlag, pp. 1085, ISBN 978-3-642-58087-1, , p. 1085, at Google Books

- ↑ Tayyem RF, Heath DD, Al-Delaimy WK, Rock CL (2006). "Curcumin content of turmeric and curry powders". Nutr Cancer. 55 (2): 126–131. doi:10.1207/s15327914nc5502_2. PMID 17044766.

- ↑ Nagpal M, Sood S (2013). "Role of curcumin in systemic and oral health: An overview". J Nat Sci Biol Med. 4 (1): 3–7. doi:10.4103/0976-9668.107253. PMC 3633300

. PMID 23633828.

. PMID 23633828. - ↑ Prasad S, Aggarwal BB (2011). Benzie IF, Wachtel-Galor S, eds. Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects. 2nd edition; Chapter 13: Turmeric, the Golden Spice. From Traditional Medicine to Modern Medicine. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1439807132. PMID 22593922. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ↑ Brennan, James (15 Oct 2008). "Turmeric". Lifestyle. The National. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- ↑ UK food guide

- ↑ Ravindran, P. N., ed. (2007). The genus Curcuma. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis. p. 244. ISBN 9781420006322.

- ↑ Berger S, Sicker D (2009). Classics in Spectroscopy. Wiley & Sons. p. 208. ISBN 978-3-527-32516-0.

- ↑ "Nabapatrika or Navapatrika – Nine leaves of plants used during Durga Puja". Hindu Blog. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- ↑ Singh KS, Bhanu BV (2004). People of India: Maharashtra, Volume 1. Popular Prakashan. pp. 2130 pages(see page:487). ISBN 9788179911006.

- ↑ Ratzel, Friedrich. The History of Mankind. (London: MacMillan, 1896). URL: www.inquirewithin.biz/history/american_pacific/oceania/oceania-utensils.htm accessed 28 November 2009.

- ↑ "Detention without physical examination of turmeric due to lead contamination". US Food and Drug Administration. 3 December 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ↑ "Producing and distributing food – guidance: Chemicals in food: safety controls; Sudan dyes and industrial dyes not permitted in food". Food Standards Agency, UK Government. 8 October 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ↑ Ragasa C, Laguardia M, Rideout J (2005). "Antimicrobial sesquiterpenoids and diarylheptanoid from Curcuma domestica". ACGC Chem Res Comm. 18 (1): 21–24.

- ↑ Mishra S, Palanivelu K (January–March 2008). "The effect of curcumin (turmeric) on Alzheimer's disease: An overview". Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 11 (1): 13–9. doi:10.4103/0972-2327.40220. PMC 2781139

. PMID 19966973.

. PMID 19966973. - ↑ Maithili Karpaga; Selvi, N.; Sridhar, M. G.; Swaminathan, R. P.; Sripradha, R. (2014). "Efficacy of turmeric as adjuvant therapy in type 2 diabetic patients.". Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry. 30 (2): 180–186. doi:10.1007/s12291-014-0436-2. PMC 4393385

. PMID 25883426.

. PMID 25883426. - ↑ Vaughn, A. R.; Branum, A; Sivamani, R. K. (2016). "Effects of Turmeric (Curcuma longa) on Skin Health: A Systematic Review of the Clinical Evidence". Phytotherapy Research. 30 (8): 1243–64. doi:10.1002/ptr.5640. PMID 27213821.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Curcuma longa. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Curcuma longa |

| Look up turmeric in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Turmeric List of Chemicals (Dr. Duke's)

- Plant Cultures: review of botany, history and uses

- Turmeric from the University of Maryland Medical Center.

- NIH.gov/books: "Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects", 2nd edition Chapter 13: Turmeric, the Golden Spice