Tutupaca

| Tutupaca | |

|---|---|

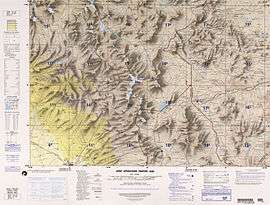

Tutupaca (upper left), Yucamane (center) and Lake Vilacota (on the right) as seen from above (NASA Landsat7 image) | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 5,815 m (19,078 ft) |

| Coordinates | 17°01′35″S 70°22′18″W / 17.02639°S 70.37167°WCoordinates: 17°01′35″S 70°22′18″W / 17.02639°S 70.37167°W |

| Geography | |

Tutupaca | |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcanoes |

| Last eruption | 1802 |

Tutupaca[1][2][3][4][5] is a twin volcano in Peru, about 5,815 metres (19,078 ft) high.[1][4] It is located in the Tacna Region, Candarave Province, Candarave District.[6] Tutupaca is situated northwest of Lake Vilacota and Yucamane volcano.[1] The northern edifice is more strongly eroded and underwent a flank collapse. The volcano has postglacial lava flows and several historical eruptions in 1802 and 1787–1789, with further eruptions suspected that might have occurred on Yucamane instead.[2] The volcano is also active with fumaroles,[7] one was reported on the northeastern flank in 1953.[3] Debris deposits are mined for sulfur.[8]

Geography

Tutupaca rises above a high plateau of 4,400 to 4,600 m (14,400 to 15,100 ft) mainly formed from sedimentary and volcanic material of Miocene-Pliocene age, and is formed from a basal edifice and two smaller ones constructed on top of it. This basal edifice, mostly of andesitic and dacitic composition and centered on the south of the two current edifices, was heavily affected by Pleistocene glaciation and hydrothermal alteration as well as a late ignimbrite eruption. Major moraines of probably Late Glacial Maximum lie in the surrounding valleys and on the basal edifice. The western (or northern) smaller edifice is a complex of lava flows and domes with Plinian eruptive activity, also affected by glacial erosion. One biotite was dated to 0.7 Ma ago. The eastern (or southern) edifice is formed by lava domes unaffected by glacial action, but is cut by a NE-open amphitheatre and containing the remnants of a summit crater. Several non-pristine lava flows are discernible. Two edifice failure events are noticeable on the southern edifice, an older channelized towards the east-southeast, and a more recent one towards the northeast. The river valleys Tacalaya and Callazas run beside the volcano complex, the latter separating it from the younger looking Yucamane. A major SE-NW-trending fault system is associated with the volcano and may be related to the formation of the amphitheatre.[7][9][10]

Recent eruption

A major eruption occurred between 1787 and 1802, causing the failure of the flank of the southern volcano with a volume of 1 km3. The collapse caused the release of pyroclastic flows with a total volume of 6.5–7.5×107 m3. The main collapse was preceded by a pyroclastic flow named Suri Phuju after the valley it is exposed in. The main debris avalanche formed levees and contains huge blocks and hummock hills. The debris deposit is overlain with a second pyroclastic flow named Paipatja that reached the Suches lake to the north of the volcano. Ash fall was reported as far as Arica, 165 km (103 mi) to the south of the volcano. This is probably the youngest debris avalanche in the Andes and one of the largest historical volcanic eruptions of Southern Peru.[9]

Future hazard

The volcano was affected by an earthquake swarm in 2001.[11] While the area surrounding the volcano is sparsely populated, a large scale eruption of Tutupaca in the future could affect 8000-10000 inhabitants in the region, as well as important geothermal and mining structures in the area.[9]

References

- 1 2 3 Peru 1:100 000, Tarata (35-v). IGN (Instituto Geográfico Nacional - Perú).

- 1 2 "Tutupaca". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- 1 2 Bullard, Fred M. (1962). "Volcanoes of Southern Peru". Bulletin Volcanologique. 24 (1): 443–453. doi:10.1007/BF02599360. ISSN 0258-8900.

- 1 2 Siebert, Lee; Simkin, Tom; Kimberly, Paul (2011). Volcanoes of the World: Third Edition. University of California Press. pp. 188,468. ISBN 9780520947931.

- ↑ Erfurt-Cooper, Patricia; Cooper, Malcolm (2010). Volcano and Geothermal Tourism. Earthscan. p. 349. ISBN 9781849775182.

- ↑ escale.minedu.gob.pe – UGEL map of the Candarave Province (Tacna Region)

- 1 2 de Silva, SL; Francis, PW (1990). "Potentially active volcanoes of Peru-Observations using Landsat Thematic Mapper and Space Shuttle imagery". Bulletin of Volcanology. 52 (4): 286–301. doi:10.1007/BF00304100. ISSN 0258-8900.

- ↑ van Wyk de Vries, Benjamin; Davies, Tim (2015). "Landslides, Debris Avalanches, and Volcanic Gravitational Deformation": 665–685. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-385938-9.00038-9.

- 1 2 3 Samaniego, Pablo; Valderrama, Patricio; Mariño, Jersy; van Wyk de Vries, Benjamín; Roche, Olivier; Manrique, Nélida; Chédeville, Corentin; Liorzou, Céline; Fidel, Lionel; Malnati, Judicaëlle (2015). "The historical (218 ± 14 aBP) explosive eruption of Tutupaca volcano (Southern Peru)". Bulletin of Volcanology. 77 (6). doi:10.1007/s00445-015-0937-8. ISSN 0258-8900.

- ↑ Tosdal, Richard M.; Farrar, Edward; Clark, Alan H. (1981). "K-Ar geochronology of the late cenozoic volcanic rocks of the Cordillera Occidental, southernmost Peru". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 10 (1–3): 157–173. doi:10.1016/0377-0273(81)90060-3. ISSN 0377-0273.

- ↑ Holtkamp, S. G.; Pritchard, M. E.; Lohman, R. B. (2011). "Earthquake swarms in South America". Geophysical Journal International. 187 (1): 128–146. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2011.05137.x. ISSN 0956-540X.

Bibliography

- Lionel Fidèl Smoll and Bilberto Zavala Carriòn (2001). Mapa preliminar de amenaza volcànica potencial de volcàn Tutupaca. Lima, Peru: Instituto Geòlogico Minero y Metalurgico, Sector Energia y Minas, Repùblica de Perù.