Typometer

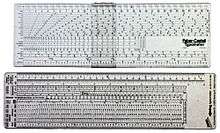

A typometer is a ruler which is usually divided in typographic points or ciceros on one of its sides and in centimeters or millimeters on the other, which was traditionally used in the graphic arts to inspect the measures of typographic materials.[1] The most developed typometers could also measure the type size of a particular typeface, the leading of a text, the width of paragraph rules and other features of a printed text. This way, designers could study and reproduce the layout of a document.

One of the domains where the typometer was most widely used was the editorial offices of newspapers and magazines, where it was used along with other tools such as tracing paper and linen testers to define the layout of the pages of the publications, until the 1980s.[2]

Typometers were initially made of wood or metal (in later times, of transparent plastic or acetate), and were produced in diverse shapes and sizes.[3] Some of them presented several scales that were used to measure the properties of the text. Each scale corresponded with a type size or with a leading unit, if line blocks were divided by blank spaces. However, typometers could not be used to measure certain computer-generated type sizes, that could be set in fractions of points.[4]

Due to the technological advancements in desktop publishing, that allow for a greater precision when setting the type size of texts, typometers have disappeared from most graphic design related professions. It keeps being used, even today, by traditional printers who still employ type metal.

History

The idea of organising type sizes according to a particular point system first appeared during the XVIIth century, in the 1723 book La Science pratique de l'imprimerie, written by French printer and bookseller Martin-Dominique Fertel.[5] In 1737, French engraver and typecaster Pierre-Simon Fournier (called Fournier the young) invented a tool in the shape of a square that he called prototype,[6] which allowed him to accurately measure type sizes. He also stablished the Fournier point, that could be used for the first time to set a correlation between a type size and a constant number of points. According to his own words,

Pour faire la combinaison des corps, il suffit de savoir le nombre de points typographiques dont ils sont composés. Il faut pour cela que les points ou grandeurs données soient invariables, de manière qu'il puissent servir de guides dans l'imprimerie, comme le pied de roi, les pouces et les lignes en servent dans la géométrie.

In order to combine type sizes, one only needs to know the number of typographic points that compose them. For that, it's important that the points or measures that are given remain constant, so they can be used as guides in the printing press, in the same way that the king's foot, the thumbs and the lines are used in geometry.— Pierre-Simon Fournier.[6]

This way, in his Table des proportions (proportions table) published in 1737, Fournier the young proposed a scale consisting in 144 typographic points on which he distributed the type sizes that were commonly used in the printing press, which ranged from the Parisienne (the smallest size, which the exception of the Perle, which was rarely used) to the Grosse nonpareille (Great nonpareil, the largest size).[7]

However, Fournier's prototype presented a major disadvantage, because its system of measures was very difficult to compare with the royal inches (pouces de roi) that were commonly used in France at the time. For this reason, French printer François-Ambroise Didot (1730–1804) created a simplified system, which he called typometer,[8] and that he based on the pied du roi.[7][9] This invention was first described in the book Essai de fables nouvelles, by Pierre Didot, François-Ambroise's son.[10]

Didot's new measuring scale was divided in 288 typographic points, instead of the former 144, and described 12 type sizes, instead of the 20 or 22 listed by Fournier the young. As many of the sizes kept their names, but changed their dimensions, a great confusion ensued among printers, and some of them campaigned for a return to the older system.[7] Nevertheless, the Didot points were progressively adopted until becoming the norm. This way of measuring type based in the mediaeval royal units prevailed even after the French Revolution, when the metric system was adopted by France.

In Germany, the French typographic point system was never properly implemented, which resulted in a wide variability of dimensions for type metal. In order to try to solve this situation, in 1879, German and Prussian printer and businessman Hermann Berthold proposed his own system to standardise typographic points based on the metric system[11] For that purpose, he divided a meter in 2660 identical typographic points. This measure, which is 0,0076 % wider than the Didot point, became the current reference for printing. From 1897 on, German manufacturer A. W. Faber started commercialising sliding rulers that allowed typographers to calculate in a simple manner the measures of their layouts.

Notes and references

- ↑ Radics, Vilmos; Ritter, Aladár (1984). Make-up and typography. International Organization of Journalists. p. 13. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

The typometer is an instrument for measuring typographical denominations: type sizes, column width and depth, slugs, type area, etc.

- ↑ Salaverría Aliaga, Ramón (2006). "El nuevo perfil profesional del periodista en el entorno digital" (PDF). Actas de las XIII Jornadas de Jóvenes Investigadores en Comunicación - Nuevos retos de la comunicación: tecnología, empresa, sociedad. Zaragoza, Spain: Universidad San Jorge: 175. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

Herramientas como la máquina de escribir con papel de calco, el tipómetro o el teletipo suenan hoy a piezas de museo. Pero debemos recordar que aún en los años 1980 eran el estándar tecnológico en las redacciones de los diarios.

- ↑ "Les outils de l'atelier". Fornax éditeur (in French). Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ↑ "Fundamentos de tipometría". Unos Tipos Duros (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ↑ Fertel, Martin-Dominique (1723). "Des caractères & de leur proportion. La comparaiſon de ces caracteres entre-eux, par rapport à leurs differens corps.". La Science pratique de l'imprimerie. Contenant des instructions trés-faciles pour se perfectionner dans cet art (in French). Saint Omer: Martin-Dominique Fertel. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- 1 2 Laboulaye, Charles (1845). Dictionnaire des arts et manufactures: A-F(1845) (in French). Librairie Scientifique-Industriel de L. Mathias (Augustin). pp. 1723–1724. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 Balleroy, J. B.; Germond, J. B. Dictionnaire des productions de la nature et de l'art, qui font l'objet du commerce, tant de la Belgique que de la France, Volumen 1 (in French). pp. 129–130. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ↑ Typometer was both the name of the system and of the tool that was used to measure type.

- ↑ Known as Paris foot in English

- ↑ Didot, Pierre (1786). Essai de fables nouvelles dédiées au roi (in French). París: François Ambroise Didot. pp. 135–136. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

Le typomètre est un étalon pour la mesure du corps des caracteres. C'est une platine d'acier, bordée en saillie par une équerre de même métal : un de ses côtés, mesuré en dedans l'équerre, est de 10 lignes et demie de pied-de-roi ; l'autre côté, mesuré également en dedans, a 48 lignes ou 288 metres, la ligne étant divise en 6 metres. Ainsi le typomètre sert à vérifier en même temps le corps des caractères et leur hauteur en papier.

- ↑ Beinert, Wolfgang (15 January 2015). "Berthold, Hermann". typolexikon.de (in German). Retrieved 22 November 2016.