Very-large-scale integration

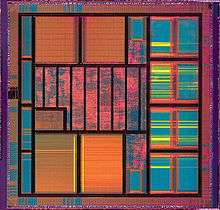

Very-large-scale integration (VLSI) is the process of creating an integrated circuit (IC) by combining thousands of transistors into a single chip. VLSI began in the 1970s when complex semiconductor and communication technologies were being developed. The microprocessor is a VLSI device. Before the introduction of VLSI technology most ICs had a limited set of functions they could perform. An electronic circuit might consist of a CPU, ROM, RAM and other glue logic. VLSI lets IC designers add all of these into one chip.

History

During the mid-1920s, several inventors attempted devices that were intended to control current in solid-state diodes and convert them into triodes. Success did not come until after World War II, during which the attempt to improve silicon and germanium crystals for use as radar detectors led to improvements in fabrication and in the understanding of quantum mechanical states of carriers in semiconductors. Then scientists who had been diverted to radar development returned to solid-state device development. With the invention of transistors at Bell Labs in 1947, the field of electronics shifted from vacuum tubes to solid-state devices.

With the small transistor at their hands, electrical engineers of the 1950s saw the possibilities of constructing far more advanced circuits. As the complexity of circuits grew, problems arose.[1]

One problem was the size of the circuit. A complex circuit, like a computer, was dependent on speed. If the components of the computer were too large or the wires interconnecting them too long, the electric signals couldn't travel fast enough through the circuit, thus making the computer too slow to be effective.[1]

Jack Kilby at Texas Instruments found a solution to this problem in 1958. Kilby's idea was to make all the components and the chip out of the same block (monolith) of semiconductor material. Kilby presented his idea to his superiors, and was allowed to build a test version of his circuit. In September 1958, he had his first integrated circuit ready.[1] Although the first integrated circuit was crude and had some problems, the idea was groundbreaking. By making all the parts out of the same block of material and adding the metal needed to connect them as a layer on top of it, there was no need for discrete components. No more wires and components had to be assembled manually. The circuits could be made smaller, and the manufacturing process could be automated. From here, the idea of integrating all components on a single silicon wafer came into existence, which led to development in small-scale integration (SSI) in the early 1960s, medium-scale integration (MSI) in the late 1960s, and then large-scale integration (LSI) as well as VLSI in the 1970s and 1980s, with tens of thousands of transistors on a single chip (later hundreds of thousands, then millions, and now billions (109)).

Developments

The first semiconductor chips held two transistors each. Subsequent advances added more transistors, and as a consequence, more individual functions or systems were integrated over time. The first integrated circuits held only a few devices, perhaps as many as ten diodes, transistors, resistors and capacitors, making it possible to fabricate one or more logic gates on a single device. Now known retrospectively as small-scale integration (SSI), improvements in technique led to devices with hundreds of logic gates, known as medium-scale integration (MSI). Further improvements led to large-scale integration (LSI), i.e. systems with at least a thousand logic gates. Current technology has moved far past this mark and today's microprocessors have many millions of gates and billions of individual transistors.

At one time, there was an effort to name and calibrate various levels of large-scale integration above VLSI. Terms like ultra-large-scale integration (ULSI) were used. But the huge number of gates and transistors available on common devices has rendered such fine distinctions moot. Terms suggesting greater than VLSI levels of integration are no longer in widespread use.

In 2008, billion-transistor processors became commercially available. This became more commonplace as semiconductor fabrication advanced from the then-current generation of 65 nm processes. Current designs, unlike the earliest devices, use extensive design automation and automated logic synthesis to lay out the transistors, enabling higher levels of complexity in the resulting logic functionality. Certain high-performance logic blocks like the SRAM (static random-access memory) cell, are still designed by hand to ensure the highest efficiency.

Structured design

Structured VLSI design is a modular methodology originated by Carver Mead and Lynn Conway for saving microchip area by minimizing the interconnect fabrics area. This is obtained by repetitive arrangement of rectangular macro blocks which can be interconnected using wiring by abutment. An example is partitioning the layout of an adder into a row of equal bit slices cells. In complex designs this structuring may be achieved by hierarchical nesting.

Structured VLSI design had been popular in the early 1980s, but lost its popularity later because of the advent of placement and routing tools wasting a lot of area by routing, which is tolerated because of the progress of Moore's Law. When introducing the hardware description language KARL in the mid' 1970s, Reiner Hartenstein coined the term "structured VLSI design" (originally as "structured LSI design"), echoing Edsger Dijkstra's structured programming approach by procedure nesting to avoid chaotic spaghetti-structured program

Struggles

As microprocessors become more complex due to technology scaling, microprocessor designers have encountered several challenges which force them to think beyond the design plane, and look ahead to post-silicon:

- Process variation – As photolithography techniques get closer to the fundamental laws of optics, achieving high accuracy in doping concentrations and etched wires is becoming more difficult and prone to errors due to variation. Designers now must simulate across multiple fabrication process corners before a chip is certified ready for production, or use system-level techniques for dealing with effects of variation.[2]

- Stricter design rules – Due to lithography and etch issues with scaling, design rules for layout have become increasingly stringent. Designers must keep ever more of these rules in mind while laying out custom circuits. The overhead for custom design is now reaching a tipping point, with many design houses opting to switch to electronic design automation (EDA) tools to automate their design process.

- Timing/design closure – As clock frequencies tend to scale up, designers are finding it more difficult to distribute and maintain low clock skew between these high frequency clocks across the entire chip. This has led to a rising interest in multicore and multiprocessor architectures, since an overall speedup can be obtained even with lower clock frequency by using the computational power of all the cores.

- First-pass success – As die sizes shrink (due to scaling), and wafer sizes go up (due to lower manufacturing costs), the number of dies per wafer increases, and the complexity of making suitable photomasks goes up rapidly. A mask set for a modern technology can cost several million dollars. This non-recurring expense deters the old iterative philosophy involving several "spin-cycles" to find errors in silicon, and encourages first-pass silicon success. Several design philosophies have been developed to aid this new design flow, including design for manufacturing (DFM), design for test (DFT), and Design for X.

See also

- Application-specific integrated circuit

- Caltech Cosmic Cube

- Design rules checking

- Electronic design automation

- Mead & Conway revolution

- Polysilicon

References

- 1 2 3 "The History of the Integrated Circuit". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 21 Apr 2012.

- ↑ "A Survey Of Architectural Techniques for Managing Process Variation", ACM Computing Surveys, 2015

Further reading

- Baker, R. Jacob (2010). CMOS: Circuit Design, Layout, and Simulation, Third Edition. Wiley-IEEE. p. 1174. ISBN 978-0-470-88132-3. http://CMOSedu.com/

- Weste, Neil H. E. & Harris, David M. (2010). CMOS VLSI Design: A Circuits and Systems Perspective, Fourth Edition. Boston: Pearson/Addison-Wesley. p. 840. ISBN 978-0-321-54774-3. http://CMOSVLSI.com/

- Chen, Wai-Kai (ed) (2006). The VLSI Handbook, Second Edition (Electrical Engineering Handbook). Boca Raton: CRC. ISBN 0-8493-4199-X.

- Mead, Carver A. and Conway, Lynn (1980). Introduction to VLSI systems. Boston: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-04358-0.

External links

- Lectures on Design and Implementation of VLSI Systems at Brown University

- List of VLSI companies around the world

- Design of VLSI Systems

- Complete VLSI Design Flow