Višegrad

| Višegrad Вишеград | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Višegrad | ||

| ||

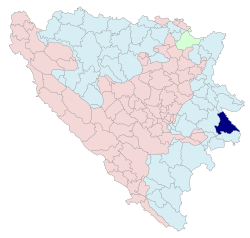

Location of Višegrad in Bosnia and Herzegovina | ||

| Coordinates: 43°47′N 19°17′E / 43.783°N 19.283°E | ||

| Country |

| |

| Entity |

| |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Mladen Đurević (SNSD) | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 448.14 km2 (173.03 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 389 m (1,276 ft) | |

| Population (2013 census) | ||

| • Total | 11,774 | |

| • Density | 26.3/km2 (68/sq mi) | |

| Postal code | 73240 | |

| Area code(s) | (+387) 058 | |

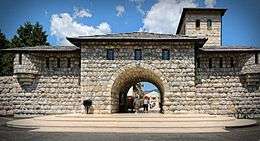

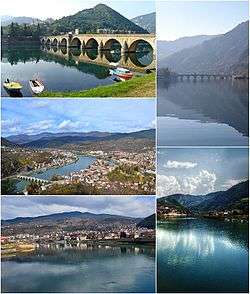

Višegrad (Serbian Cyrillic: Вишеград, pronounced [ʋǐʃɛɡraːd]) is a town and municipality in eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina resting on the River Drina and in the Republika Srpska entity. The town includes the Ottoman-era Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge, a UNESCO world heritage site which was popularized by Nobel prize-winning author Ivo Andrić in his novel The Bridge on the Drina. A tourist site dedicated to Andrić is located near the bridge. Known as Andrićgrad, it was officially opened on 28 June 2014.[1] During the Bosnian War the town was one of the scenes of ethnic cleansing and massacres carried out by Bosnian Serb forces against Bosniak civilians,[2] and it saw a drastic decline in its previous majority Bosniak population.[3] Višegrad is a South Slavic toponym meaning "the upper town/castle/fort". Višegrad is located on the River Drina, on the road from Goražde and Ustiprača towards Užice, Serbia.

Geography

Višegrad is located on the River Drina, which is part of the geographical region of Podrinje. It is also part of the historical region of Stari Vlah; the immediate area surrounding the town was historically called "Višegradski Stari Vlah",[4][5] noted as an ethnographic region[6] in which the population was closer to Užice, located on the Serbian side of the River Drina, than to the surrounding areas.[4]

History

Middle Ages

The area was part of the medieval Serbian state of the Nemanjić dynasty; it was part of the Grand Principality of Serbia under Stefan Nemanja (r. 1166–96). In the Middle Ages, Dobrun was a place within the border area with Bosnia, on the road towards Višegrad. After the death of Emperor Stefan Dušan (r. 1331–55), the region came under the rule of magnate Vojislav Vojinović, and then his nephew, župan (count) Nikola Altomanović.[7][8] The Dobrun Monastery was founded by župan Pribil and his family,[9] some time before the 1370s. The area then came under the rule of the Kingdom of Bosnia, part of the estate of the Pavlović noble family.[10]

The settlement of Višegrad is mentioned in 1407, but is starting to be more often mentioned after 1427.[11] In the period of 1433–37, a relatively short period, caravans crossed the settlement many times.[11] Many people from Višegrad worked for the Republic of Ragusa.[11] Srebrenica and Višegrad and its surroundings were again in Serbian hands in 1448 after Despot Đurađ Branković defeated Bosnian forces.[12]

According to Turkish sources, in 1454, Višegrad was conquered by the Ottoman Empire led by Osman Pasha. It remained under the Ottoman rule until the Berlin Congress (1878), when Austria-Hungary took control of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Ottoman period

The Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge was built by the Ottoman architect and engineer Mimar Sinan for Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha. Construction of the bridge took place between 1571 and 1577. It still stands, and it is now a tourist attraction, after being inscribed in the UNESCO World Heritage Site list.[13]

In 1875, the Serbs from the area between Višegrad and Novi Pazar revolted and formed a volunteer military corps, who fought in the valley of the River Ibar in 1876.[14]

Austro-Hungarian period

The Bosnian Eastern Railway from Sarajevo to Uvac and Vardište was built through Višegrad during the Austro-Hungarian rule in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Construction of the line started in 1903. It was completed in 1906, using the 760 mm (2 ft 5 15⁄16 in) track gauge. With the cost of 75 million gold crowns, which approximately translates to 450 thousand gold crowns per kilometer, it was one of the most expensive railways in the world built by that time.[15] This part of the line was eventually extended to Belgrade in 1928.[16] Višegrad is today part of the narrow-gauge heritage railway Šargan Eight.

World War II

The area was a site of Partisan–German battles.[17]

Bosnian War

Višegrad is one of several towns along the River Drina in close proximity to the Serbian border. The town was strategically important during the conflict. A nearby hydroelectric dam provided electricity and also controlled the level of the River Drina, preventing flooding downstream areas. The town is situated on the main road connecting Belgrade and Užice in Serbia with Goražde and Sarajevo in Bosnia and Herzegovina, a vital link for the Užice Corps of the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) with the Uzamnica camp as well as other strategic locations implicated in the conflict.[18][19]

On 6 April 1992, JNA artillery bombarded the town, in particular Bosniak-inhabited neighbourhoods and nearby villages. Murat Šabanović and a group of Bosniak men took several local Serbs hostage and seized control of the hydroelectric dam, threatening to blow it up. Water was released from the dam causing flooding to some houses and streets.[19] Eventually on 12 April, JNA commandos seized the dam. The next day the JNA's Užice Corps took control of Višegrad, positioning tanks and heavy artillery around the town. The population that had fled the town during the crisis returned and the climate in the town remained relatively calm and stable during the later part of April and the first two weeks of May.[19] On 19 May 1992 the Užice Corps officially withdrew from the town and local Serb leaders established control over Višegrad and all municipal government offices. Soon after, local Serbs, police and paramilitaries began one of the most notorious campaigns of ethnic cleansing in the conflict.[19]

There was widespread looting and destruction of houses, and terrorizing of Bosniak civilians, with instances of rape, with a large number of Bosniaks killed in the town, with many bodies were dumped in the River Drina. Men were detained at the barracks at Uzamnica, the Vilina Vlas Hotel and other sites in the area. Vilina Vlas also served as a "brothel", in which Bosniak women and girls (some not yet 14 years old), were brought to by police officers and paramilitary members (White Eagles and Arkan's Tigers).[20] Bosniaks detained at Uzamnica were subjected to inhumane conditions, including regular beatings, torture and strenuous forced labour. Both of the town's mosques were razed.[18][19][21] According to victims' reports some 3,000 Bosniaks were murdered in Višegrad and its surroundings, including some 600 women and 119 children.[22][23] According to the Research and Documentation Center, at least 1661 Bosniaks were killed/missing in Višegrad.[24]

With the Dayton Agreement, which put an end to the war, Bosnia and Herzegovina was divided into two entities, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska, the latter which Višegrad became part of.

Before the war, 63% of the town residents were Bosniak. In 2009, only a handful of survivors had returned to what is now a predominantly Serb town.[25] On 5 August 2001, survivors of the massacre returned to Višegrad for the burial of 180 bodies exhumed from mass graves. The exhumation lasted for two years and the bodies were found in 19 different mass graves.[26] The charges of mass rape were unapproved as the prosecutors failed to request them in time.[27] Cousins Milan Lukić and Sredoje Lukić were convicted on July 20, 2009, to life in prison and 30 years, respectively, for a 1992 killing spree of Muslims.[18][28]

Architecture

- Andrićgrad, town built by Serbian filmmaker Emir Kusturica, dedicated to Ivo Andrić.

- Dobrun Monastery, a Serbian Orthodox monastery founded one of the most notable monasteries of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[29]

Sport

The local football club, FK Drina HE Višegrad, competes in the First League of the Republika Srpska.

Culture

The House of Culture was founded in 1953. Film screenings and other cultural activities take place in there, including amateur drama programs. The City Gallery, which was opened in 1996, is located in the House of Culture.[30] There is also a folk dance ensemble operating in Višegrad under the name KUD "Bikavac".[31]

Demographics

Municipality

According to the 1991 Census, the municipality of Višegrad had a population of 21,199 residents.[32]

| Census of the Municipality of Višegrad | ||||||

| Year | 1991. | 1981. | 1971. | |||

| Bosniaks | 13,471 (63.54%) | 14,397 (62.05%) | 15,752 (62.04%) | |||

| Serbs | 6,743 (31.80%) | 7,648 (32.96%) | 9,225 (36.33%) | |||

| Croats | 32 (0.15%) | 60 (0.25%) | 68 (0.26%) | |||

| Yugoslavs | 319 (1.50%) | 758 (3.26%) | 141 (0.55%) | |||

| Others | 634 (3.37%) | 338 (1.45%) | 203 (0.79%) | |||

| Total | 21,199 | 23,201 | 25,389 | |||

Town

According to the 1991 Census, the town of Višegrad had a population of 11,828 residents.[32]

| Census of the Town of Višegrad | ||||||

| Year | 1991. | 1981. | 1971. | |||

| Bosniaks | 7,413 (62.67%) | 2,854 (47.66%) | 2,429 (49.91%) | |||

| Serbs | 3,512 (29.69%) | 2,446 (40.84%) | 2,141 (43.99%) | |||

| Croats | 28 (0.24%) | 52 (0.86%) | 53 (1.08%) | |||

| Yugoslavs | 300 (2.5%) | 518 (8.65%) | 107 (2.19%) | |||

| Others | 575 (4.9%) | 118 (1.97%) | 136 (2.79%) | |||

| Total | 11,828 | 5,988 | 4,866 | |||

References

- ↑ Aspden, Peter (27 June 2014). "The town that Emir Kusturica built". Financial Times. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ Russell, Alec (23 March 2012). "Unforgiven, unforgotten, unresolved: Bosnia 20 years on". Financial Times. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ "Crimes before the ICTY: Višegrad". icty.org. United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY). Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- 1 2 Biblioteka Nasi Krajevi. 4. 1963. pp. 16–22.

- ↑ Petar Vlahović (2004). Serbia: the country, people, life, customs. Ethnographic Museum. p. 31. ISBN 978-86-7891-031-9.

- ↑ Etnološki pregled: Revue d'ethnologie. 12-14. 1974. p. 83.

- ↑ Синиша Мишић (2010). Лексикон градова и тргова средњовековних српских земаља: према писаним изворима. Завод за уџбенике. pp. 73–. ISBN 978-86-17-16604-3.

У ово време Добрун је у саставу државе Немањића и то у пограничном подручју с Босном, на путу који води за Вишеград. После смрти цара Душана (1355) припадао је кнезу Војиславу Војиновићу, а затим његовом синовцу ...

- ↑ Etnografski institut (1950). Zbornik radova Etnografskog instituta. 17-18. SANU. p. 18.

- ↑ Драгиша Милосављевић (2006). Средњевековни град и манастир Добрун. Дерета. p. 104. ISBN 978-86-7346-570-8.

Били су то жупан Прибил н>егови синови Петар и Стефан и jедна ман>е позната лич- ност знатно вишег ранга - nротоовесrajар Стан - юуи jе као такав и представл>ен у ктиторскоj поворци у Добруну.20 Вероватно пе временом ...

- ↑ Историјски гласник: орган Друштва историчара СР Србије. Друштво. 1981.

... земље Павловића простирале су се од Добруна, на истоку, до Врхбосне на западу. ...

- 1 2 3 Desanka Kovačević-Kojić (1978). Agglomérations urbaines dans l'état médiéval bosniaque. Veselin Masleša. p. 99.

- ↑ Milan Vasić (1995). Bosna i Hercegovina od srednjeg veka do novijeg vremena: međunarodni naučni skup 13-15. decembar 1994. Istorijski institut SANU. pp. 98–99.

- ↑ "Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge in Višegrad". whc.unesco.org. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ Gale Stokes (1990). Politics as development: the emergence of political parties in nineteenth century Serbia. Duke University Press. p. 335.

- ↑ "Narrow-gauge railway in Višegrad". visegradturizam.com. Tourist organization of Višegrad. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ "Uskotračne željeznice - Grafikoni" [Narrow-gauge railways - Graphs]. zeljeznice.net (in Croatian). Retrieved 17 September 2016. (registration required (help)).

- ↑ Dušan Trbojević (1998). Cersko-Majevička grupa korpusa, 1941-1945: pod komandom pukovnika Dragoslava S. Račića. D. Trbojević.

- 1 2 3 "ICTY: Milan Lukić and Sredoje Lukić judgement" (PDF).

- 1 2 3 4 5 "ICTY: Mitar Vasiljević judgement" (PDF).

- ↑ Final report of the United Nations Commission of Experts, established pursuant to security council resolution 780 (1992), Annex VIII - Prison camps; Under the Direction of: M. Cherif Bassiouni; S/1994/674/Add.2 (Vol. IV), 27 May 1994

- ↑ Final report of the United Nations Commission of Experts established pursuant to security council resolution 780 Archived February 3, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Damir Kaletovic. "Bosnia's ideal fugitive hideout". International Relations and Security Network.

- ↑ "Hope for Bosnia town whose bridge will shine again". Reuters. May 26, 2007.

- ↑ "IDC: Podrinje victim statistics". Archived from the original on 2007-07-07.

- ↑ "Visegrad in Denial Over Grisly Past". Institute for War and Peace Reporting. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ↑ "Bosnian Institute News: Has anyone seen Milan Lukic?". Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ↑ Investigation: Visegrad rape victims say their cries go unheard Archived June 18, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Hague: Bosnian Serbs Sentenced". The New York Times. 21 July 2009. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ↑ Политика, издање од 6. јануара 2008. године

- ↑ "Javne ustanove za kulturu" [Cultural institutions]. visegradturizam.com (in Serbian). Tourist organization of Višegrad. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ "Kulturno umjetnička društva" [Culture and art associations]. visegradturizam.com (in Serbian). Tourist organization of Višegrad. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- 1 2 "Popis stanovništva 1991" [1991 Census]. fzs.ba (in Bosnian). Federal Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

Sources

- Stjepo Trifković (1903). Višegradski Stari Vlah. Srpska kraljevska akademija.

External links

![]() Media related to Višegrad at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Višegrad at Wikimedia Commons

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Višegrad. |

- Official presentation of Tourist organization of Visegrad

- visegrad.rs Tourist attractions and services in Visegrad

- Visegrad24.info

Coordinates: 43°46′58″N 19°17′28″E / 43.78278°N 19.29111°E

.svg.png)