Lake Victoria

| Lake Victoria (Nalubaale) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | African Great Lakes |

| Coordinates | 1°S 33°E / 1°S 33°ECoordinates: 1°S 33°E / 1°S 33°E |

| Primary inflows | Kagera River |

| Primary outflows | White Nile (river, known as the "Victoria Nile" as it flows out of the lake) |

| Catchment area |

184,000 km2 (71,000 sq mi) 238,900 km2 (92,200 sq mi) basin |

| Basin countries |

Tanzania Uganda Kenya |

| Max. length | 337 km (209 mi) |

| Max. width | 250 km (160 mi) |

| Surface area | 68,800 km2 (26,600 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 40 m (130 ft) |

| Max. depth | 83 m (272 ft) |

| Water volume | 2,750 km3 (660 cu mi) |

| Shore length1 | 3,440 km (2,140 mi) |

| Surface elevation | 1,133 m (3,717 ft) |

| Islands | 84 (Ssese Islands, Uganda; Maboko Island, Kenya) |

| Settlements | |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. | |

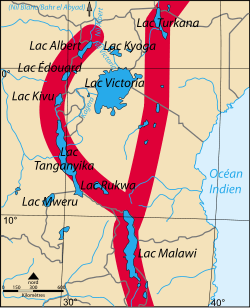

Lake Victoria (Nam Lolwe in Luo; Nalubaale in Luganda; Nyanza in Kinyarwanda and some Bantu languages)[1] is one of the African Great Lakes. The lake was named after Queen Victoria by the explorer John Hanning Speke, the first Briton to document it. Speke accomplished this in 1858, while on an expedition with Richard Francis Burton to locate the source of the Nile River.[2][3]

With a surface area of approximately 68,800 km2 (26,600 sq mi),[4][5] Lake Victoria is Africa's largest lake by area, the world's largest tropical lake,[6] and the world's second largest fresh water lake by surface area, after Lake Superior in North America.[7] In terms of volume, Lake Victoria is the world's ninth largest continental lake, containing about 2,750 cubic kilometres (2.23×109 acre·ft) of water.[8]

Lake Victoria receives its water primarily from direct rainfall and thousands of small streams. The Kagera River is the largest river flowing into this lake, with its mouth on the lake's western shore. Lake Victoria is drained solely by the Nile River near Jinja, Uganda, on the lake's northern shore.[4]

Lake Victoria occupies a shallow depression in Africa; it has a maximum depth of 84 m (276 ft) and an average depth of 40 m (130 ft).[9] Its catchment area covers 184,000 km2 (71,000 sq mi). The lake has a shoreline of 7,142 km (4,438 mi) when digitized at the 1:25,000 level,[10] with islands constituting 3.7 percent of this length,[11] and is divided among three countries: Kenya (6 percent or 4,100 km2 or 1,600 sq mi), Uganda (45 percent or 31,000 km2 or 12,000 sq mi), and Tanzania (49 percent or 33,700 km2 or 13,000 sq mi).[12]

Geology

During its geological history, Lake Victoria went through changes ranging from its present shallow depression, through to what may have been a series of much smaller lakes.[11] Geological cores taken from its bottom show Lake Victoria has dried up completely at least three times since it formed.[13] These drying cycles are probably related to past ice ages, which were times when precipitation declined globally.[13] Lake Victoria last dried out 17,300 years ago, and it refilled beginning about 14,700 years ago. Geologically, Lake Victoria is relatively young – about 400,000 years old – and it formed when westward-flowing rivers were dammed by an upthrown crustal block.[13]

This geological history probably contributed to the dramatic cichlid speciation that characterises its ecology, as well as that of other African Great Lakes.[14] Some researchers dispute this, arguing that while Lake Victoria was at its lowest between 18,000 and 14,000 years ago, and it dried out at least once during that time, there is no evidence of remnant ponds or marshes persisting within the desiccated basin. If such features existed, then they would have been small, shallow, turbid, and/or saline, and therefore markedly different from the lake to which today's species are adapted.[15]

Its outflow controlled by the Nalubaale Power Station and associated barrages, the lake itself is much less vulnerable than endorheic lakes to drops in rainfall, but the level of precipitation has a direct impact on the chief water supply of the main agricultural lands to the north in South Sudan, Sudan, and Egypt.

Hydrology and limnology

Lake Victoria receives 80 percent of its water from direct rainfall.[11] Average evaporation on the lake is between 2.0 and 2.2 metres (6.6 and 7.2 ft) per year, almost double the precipitation of riparian areas.[16] In the Kenya Sector, the main influent rivers are the Sio, Nzoia, Yala, Nyando, Sondu Miriu, Mogusi, and Migori. Combined, these rivers contribute far more water to the lake than does the largest single river which enters the lake from the west, the Kagera River.[17]

The only outflow from Lake Victoria is the Nile River, which exits the lake near Jinja, Uganda. In terms of contributed water, this makes Lake Victoria the principal source of the longest branch of the Nile; however, the most distal source of the Nile Basin, and therefore the ultimate source of the Nile, is more often considered to be one of the tributary rivers of the Kagera River (the exact tributary remains undetermined), and which originates in either Rwanda or Burundi. The uppermost section of the Nile is generally known as the Victoria Nile until it reaches Lake Albert. Although it is a part of the same river system known as the White Nile and is occasionally referred to as such, strictly speaking this name does not apply until after the river crosses the Uganda border into South Sudan to the north.

The lake exhibits eutrophic conditions. In 1990–1991, oxygen concentrations in the mixed layer were higher than in 1960–1961, with nearly continuous oxygen supersaturation in surface waters. Oxygen concentrations in hypolimnetic waters (i.e. the layer of water that lies below the thermocline, is noncirculating, and remains perpetually cold) were lower in 1990–1991 for a longer period than in 1960–1961, with values of less than 1 mg per litre (< 0.4 gr/cu ft) occurring in water as shallow as 40 metres (130 ft) compared with a shallowest occurrence of greater than 50 metres (160 ft) in 1961. The changes in oxygenation are considered consistent with measurements of higher algal biomass and productivity.[18] These changes have arisen for multiple reasons: successive burning within its basin,[19] soot and ash from which has been deposited over the lake's wide area; from increased nutrient inflows via rivers,[20] and from increased pollution associated with settlement along its shores.

The extinction of cichlids in the genus Haplochromis has also been blamed on the lake's eutrophication. The fertility of tropical waters depends on the rate at which nutrients can be brought into solution. The influent rivers of Lake Victoria provide few nutrients to the lake in relation to its size. Because of this, most of Lake Victoria's nutrients are thought to be locked up in lake-bottom deposits.[11][21] By itself, this vegetative matter decays slowly. Animal flesh decays considerably faster, however, so the fertility of the lake is dependent on the rate at which these nutrients can be taken up by fish and other organisms.[21] There is little doubt that Haplochromis played an important role in returning detritus and plankton back into solution.[22][23][24] With some 80% of Haplochromis species feeding off detritus, and equally capable of feeding off one another, they represented a tight, internal recycling system, moving nutrients and biomass both vertically and horizontally through the water column, and even out of the lake via predation by humans and terrestrial animals. The removal of Haplochromis, however, may have contributed to the increasing frequency of algal blooms,[20][23][24] which may in turn be responsible for mass fish kills.[20]

Bathymetry

The lake is considered a shallow lake considering its large geographic area with a maximum depth of approximately 80 meters and an average depth of almost exactly 40 meters.[26] A 2016 project digitized ten-thousand points and created the fist true bathymetric map of the lake.[27] The deepest part of the lake is offset to the east of the lake near Kenya and the lake is generally shallower in the west along the Ugandan shoreline and the south along the Tanzanina shoreline.[25]

Fisheries

Lake Victoria supports Africa's largest inland fishery (as of 1997).[28]

Environmental issues

A number of environmental issues are associated with Lake Victoria.

Invasive species

The introduction of exotic fish species, especially the Nile perch, has altered the freshwater ecosystem of the lake and driven several hundred species of native cichlids to near or total extinction. In the 1950s, a proposal to increase fish catches in the lake by introducing the Nile perch (mbutta or Sangara) was adamantly opposed by scientists who feared that the lack of a natural predator for the non-native species would result in the imminent destruction of the lake's bountiful ecosystem.

Despite the controversy, a colonial fisheries officer was ordered to clandestinely put the Nile perch into the portion of the lake that is in Uganda in 1952. Thereafter, it was introduced intentionally in both 1962 and 1963. And by 1964 Mbutta or Sangara was recorded in Tanzania, by 1970 it was well established in Kenya, and by the early 1980s it was abundant throughout Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda, the three countries surrounding the lake.

Now in fifty years' time or less, virtually the entire natural, biological "wealth" unique to Lake Victoria has been destroyed. At one time, the lake contained over 350 endemic species of haplochromines whose extraordinary diversity, and speed of evolution, were inspiring to scientists concerned with the forces that create and maintain the richness of life everywhere. Today, only a handful of species struggle to exist, threatened on one hand by an invasive species (the Nile perch) and on the other hand by the lake's changing conditions.

Due to the presence of the Nile perch, the natural balance of the lake's ecosystem has been disrupted. The food chain is being altered and in some cases, broken by the indiscriminate eating habits of the Nile perch. The subsequent decrease in the member of algae-eating fish allows the algae to grow at an alarming rate, thereby choking the lake. The increasing amounts of algae, in turn, increase the amount of detritus (dead plant material) that falls to the deeper portions of the lake before decomposing. As a by-product of this the oxygen levels in the deeper layer of water are being depleted. Without oxygen, any aerobic life (such as fish) cannot exist in the deeper parts of the lake, forcing all life to exist within a narrow range of depth. In this way, the Nile perch has degraded the diverse and thriving ecosystem that was once Lake Victoria. The abundance of aquatic life is not the only dependent of the lake: more than thirty million people in Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda rely on the lake for its natural resources.

The fishing industry, in particular, is also suffering. With traditional food sources all but extinct, and nets continuously damaged from the sheer force of the Nile perch, local fisheries have to abandon their work. The costs of scarce wood that is burned to dry the fish and of large processing plants that are built to prepare the fish for market preclude many fisheries from entering the Nile perch market. Only fisheries with large financial standings have been able to switch to catching the fish. As the Nile perch's food supply dwindles over time, so does its population, making these fisheries unsustainable. Having no natural predators in the lake and a plethora of food, The Nile perch flourished, often reaching up to 240 kg. Such eating habits are no longer sustainable. The fish has caused mass extinctions among haplochromine populations. And with few available food sources remaining, the Nile perch has taken to cannibalism, with the larger fish feasting on the smaller ones.

Hundreds of endemic species that evolved under the special conditions offered by the protection of Lake Victoria have been lost due to extinction, and several more are still threatened. Their loss is devastating for the lake, the fields of ecology, genetics and evolution biology, and more evidently, for the local fisheries. Local fisheries once depended on catching the lungfish, tilapia, carp and catfish that comprise the local diet. Today, the composition and yields of such fish catches are virtually negligible. Extensive fish kills, Nile perch, loss of habitat and overfishing have caused many fisheries to collapse and many protein sources to be unavailable at the market for local consumption. Few fisheries, though, have been able to make the switch to catching the Nile perch, since that requires a significant amount of capital resources.[29]

Water hyacinth invasion

The Water hyacinth has become a major invasive plant species in Lake Victoria. The release of large amounts of untreated wastewater (sewage), agricultural and industrial runoff directly into Lake Victoria over the past 30 years, has greatly increased the nutrient levels of nitrogen and phosphorus in the lake "triggering massive growth of exotic Water hyacinth, which colonised the lake in the late 1990s".[30][31] This invasive weed creates anoxic (total depletion of oxygen levels) conditions in the lake inhibiting decomposing plant material, raising toxicity and disease levels to both fish and people. At the same time the plant's mat or "web" creates a barrier for boats and ferries to maneuver, impedes access to the shoreline, interferes with hydroelectric power generation, and blocks the intake of water for industries.[30][32][33][34][35] On the other hand, Water hyacinth mats can potentially have a positive effect on fish life in that they create a barrier to overfishing and allow for fish growth, there has even been the reappearance of some fish species thought to have been extinct in recent years. However, the overall effects of the Water hyacinth are still unknown.[32][36]

Growth of the Water hyacinth in Lake Victoria has been tracked since 1993, reaching its maxima biomass in 1997 and then declining again by the end of 2001.[32] Greater growth was observed in the northern part of the lake, in relatively protected areas, which may be linked to current and weather patterns and could also be due to the climate and water conditions, which are more suitable to the plants growth (as there are large urban areas to the north end of the lake, in Uganda).[35] The invasive weed was first attempted to be controlled by hand, removed manually from the lake, however, re-growth occurred quickly. Public awareness exercises were also conducted.[35] More recently, measures have been used such as the introduction of natural insect predators, including two different Water hyacinth weevils and large harvesting and chopping boats, which seem to be much more effective in eliminating the Water hyacinth.[35][37][38][39]

Other factors which may have contributed to the decline of the Water hyacinth in Lake Victoria include varying weather patterns, such as El Nino during the last few months of 1997 and first six months of 1998 bringing with it higher levels of water in the lake and thus dislodging the plants. Heavy winds and rains along with their subsequent waves may have also damaged the plants during this same time frame. The plants may not have been destroyed however, simply moved to another location. Additionally, the water quality and nutrient supply, temperature and other environmental factors could have played a role. Overall the timing of decline could be linked to all of these factors and perhaps together, in combination, they were more effective than any one deterrent would have been by itself.[35] The Water hyacinth is in remission and this trend could be permanent if control efforts are continued.[40]

Pollution

Pollution of Lake Victoria is mainly due to discharge of raw sewage into the lake, dumping of domestic and industrial waste, and fertiliser and chemicals from farms.

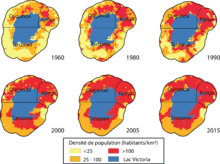

The Lake Victoria basin while generally rural has many major centres of population. Its shores in particular are dotted with the key cities and towns, including Kisumu, Kisii, and Homa Bay in Kenya; Kampala, Jinja and Entebbe in Uganda; and Bukoba, Mwanza and Musoma in Tanzania. These cities and towns also are home to many factories that discharge some chemicals directly into the lake or its influent rivers. Large parts of these urban areas also discharge untreated (raw) sewage into the river, increasing its eutrophication that in turn is helping to increase the invasive water hyacinth.[41]

Environmental Data

As of 2016, an environmental data repository exists for Lake Victoria. The repository contains shoreline, bathymetry, pollution, temperature, wind vector, and other important data for both the lake and the wider Basin.

History and exploration

The first recorded information about Lake Victoria comes from Arab traders plying the inland routes in search of gold, ivory, other precious commodities, and slaves. An excellent map, known as the Muhammad al-Idrisi map from the calligrapher who developed it and dated from the 1160s, clearly depicts an accurate representation of Lake Victoria, and attributes it as the source of the Nile.

The lake was first sighted by a European in 1858 when the British explorer John Hanning Speke reached its southern shore while on his journey with Richard Francis Burton to explore central Africa and locate the Great Lakes. Believing he had found the source of the Nile on seeing this "vast expanse of open water" for the first time, Speke named the lake after Queen Victoria. Burton, who had been recovering from illness at the time and resting further south on the shores of Lake Tanganyika, was outraged that Speke claimed to have proved his discovery to have been the true source of the Nile, which Burton regarded as still unsettled. A very public quarrel ensued, which not only sparked a great deal of intense debate within the scientific community of the day, but also much interest by other explorers keen to either confirm or refute Speke's discovery.[42]

In the late 1860s, the famous British explorer and missionary David Livingstone failed in his attempt to verify Speke's discovery, instead pushing too far west and entering the River Congo system instead.[43] Ultimately, the Welsh-American explorer Henry Morton Stanley, on an expedition funded by the New York Herald newspaper, confirmed the truth of Speke's discovery, circumnavigating the lake and reporting the great outflow at Ripon Falls on the lake's northern shore.

Nalubaale Dam

The only outflow for Lake Victoria is at Jinja, Uganda, where it forms the Victoria Nile. The water since at least 12,000 years ago drained across a natural rock weir. In 1952, engineers acting for the government of British Uganda blasted out the weir and reservoir to replace it with an artificial barrage to control the level of the lake and reduce the gradual erosion of the rock weir. A standard for mimicking the old rate of outflow called the "agreed curve" was established, setting the maximum flow rate at 300 to 1,700 cubic metres per second (392–2,224 cu yd/sec) depending on the lake's water level.

In 2002, Uganda completed a second hydroelectric complex in the area, the Kiira Hydroelectric Power Station, with World Bank assistance. By 2006, the water levels in Lake Victoria had reached an 80-year low, and Daniel Kull, an independent hydrologist living in Nairobi, Kenya, calculated that Uganda was releasing about twice as much water as is allowed under the agreement,[44] and was primarily responsible for recent drops in the lake's level.

Transport

Since the 1900s, Lake Victoria ferries have been an important means of transport between Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya. The main ports on the lake are Kisumu, Mwanza, Bukoba, Entebbe, Port Bell and Jinja. Until Kenyan independence in 1963, the fastest and newest ferry, MV Victoria, was designated a Royal Mail Ship. In 1966, train ferry services between Kenya and Tanzania were established with the introduction of MV Uhuru and MV Umoja. The ferry MV Bukoba sank in the lake on May 21, 1996, with a loss of between 800 and 1,000 lives, making it one of Africa's worst maritime disasters.

See also

References

- ↑ "The Victoria Nyanza. The Land, the Races and their Customs, with Specimens of Some of the Dialects". World Digital Library. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ↑ Dalya Alberge (11 September 2011). "How feud wrecked the reputation of explorer who discovered Nile's source". The Observer. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ↑ Moorehead, Alan (1960). "Part One: Chapters 1–7". The White Nile. Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-095639-9.

- 1 2 vanden Bossche, J.-P.; Bernacsek, G. M. (1990). Source Book for the Inland Fishery Resources of Africa, Issue 18, Volume 1. Food and Agriculture Organization, United Nations. p. 291. ISBN 92-5-102983-0. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ↑ "Fishnet, Lake Victoria, Vector Polygon, ~2015 - LakeVicFish Dataverse". doi:10.7910/dvn/lrshef.

- ↑ Peter Saundry. "Lake Victoria".

- ↑ "Lake Victoria". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ Holtzman J.; Lehman J. T. (1998). "Role of apatite weathering in the eutrophication of Lake Victoria". In John T. Lehman. Environmental Change and Response in East African Lakes. Springer Netherlands. pp. 89–98. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-1437-2_7. ISBN 978-94-017-1437-2.

- ↑ United Nations, Development and Harmonisation of Environmental Laws Volume 1: Report on the Legal and Instituional Issues in the Lake Victoria Basin, United Nations, 1999, page 17

- ↑ "Shoreline, Lake Victoria, vector line, ~2015 - LakeVicFish Dataverse". doi:10.7910/dvn/5y5ivf.

- 1 2 3 4 C. F. Hickling (1961). Tropical Inland Fisheries. London: Longmans.

- ↑ J. Prado, R. J. Beare, J. Siwo Mbuga & L. E. Oluka, 1991. A catalogue of fishing methods and gear used in Lake Victoria. UNDP/FAO Regional Project for Inland Fisheries Development (IFIP), FAO RAF/87/099-TD/19/91 (En). Rome, Food and Agricultural Organization.

- 1 2 3 John Reader (2001). Africa. Washington, D. C.: National Geographic Society. pp. 227–228. ISBN 0-7922-7681-7.

- ↑ Christian Sturmbauer; Sanja Baric; Walter Salzburger; Lukas Rüber; Erik Verheyen (2001). "Lake level fluctuations synchronize genetic divergences of cichlid fishes in African lakes" (PDF). Molecular Biology and Evolution. 18: 144–154. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003788. PMID 11158373.

- ↑ J. C. Stager; T. C. Johnson (2008). "The late Pleistocene desiccation of Lake Victoria and the origin of its endemic biota". Hydrobiologia. 596 (1): 5–16. doi:10.1007/s10750-007-9158-2.

- ↑ Simeon H. Ominde (1971). "Rural economy in West Kenya". In S. H. Ominde. Studies in East African Geography and Development. London: Heinemann Educational Books Ltd. pp. 207–229. ISBN 0-520-02073-1.

- ↑ P. J. P. Whitehead (1959). "The river fisheries of Kenya 1: Nyanza Province". East African Agricultural and Forestry Journal. 24 (4): 274–278.

- ↑ R. E. Hecky; F. W. B. Bugenyi; P. Ochumba; J. F. Talling; R. Mugidde; M. Gophen; L. Kaufman (1994). "Deoxygenation of the deep water of Lake Victoria, East Africa". Limnology and Oceanography. 39 (6): 1476–1481. doi:10.4319/lo.1994.39.6.1476. JSTOR 2838147.

- ↑ R. E. Hecky (1993). "The eutrophication of Lake Victoria". Verhandlungen der Internationale Vereinigung für Limnologie. 25: 39–48.

- 1 2 3 Peter B. O. Ochumba; David I. Kibaara (1989). "Observations on blue-green algal blooms in the open waters of Lake Victoria, Kenya". African Journal of Ecology. 27 (1): 23–34. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1989.tb00925.x.

- 1 2 R. S. A. Beauchamp (1954). "Fishery research in the lakes of East Africa". East African Agricultural Journal. 19 (4): 203–207.

- ↑ Lucy Richardson, The lessons of Lake Victoria Uganda

- 1 2 Les Kaufman; Peter Ochumba (1993). "Evolutionary and conservation biology of cichlid fishes as revealed by faunal remnants in northern Lake Victoria". Conservation Biology. 7 (3): 719–730. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1993.07030719.x. JSTOR 2386703.

- 1 2 Tijs Goldschmidt; Frans Witte; Jan Wanink (1993). "Cascading effects of the introduced Nile perch on the detrivorous/phytoplantivorous species in sublittoral areas of Lake Victoria". Conservation Biology. 7 (3): 686–700. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1993.07030686.x. JSTOR 2386700.

- 1 2 "Bathymetry TIFF, Lake Victoria Bathymetry, raster, 2016 - LakeVicFish Dataverse". doi:10.7910/dvn/soeknr.

- ↑ "LV_Bathy". faculty.salisbury.edu. Retrieved 2016-10-24.

- ↑ "Bathymetry TIFF, Lake Victoria Bathymetry, raster, 2016 - LakeVicFish Dataverse". doi:10.7910/dvn/soeknr.

- ↑ Kim Geheb (1997). The Regulators and the regulated: fisheries management, options and dynamics in Kenya's Lake Victoria Fishery (Ph.D. thesis). University of Sussex.

- ↑ http://www.homehighlight.org/entertainment-and-recreation/nature/nile-perch-and-the-future-of-lake-victoria.html

- 1 2 Luilo, G. B. (August 01, 2008). Lake Victoria water resources management challenges and prospects: a need for equitable and sustainable institutional and regulatory frameworks. African Journal of Aquatic Science, 33, 2, 105-113.

- ↑ Muli, J., Mavutu, K., and Ntiba, J. (2000) Micro-invertebrate fauna of water hyacinth in Kenyan waters of Lake Victoria. International Journal of Ecology and Environmental Science 20: 281–302

- 1 2 3 Kateregga, E., & Sterner, T. (January 01, 2009). Lake Victoria Fish Stocks and the Effects of Water Hyacinth. Journal of Environment & Development, 18, 1, 62-78.

- ↑ Mailu, A. M., G. R. S. Ochiel, W. Gitonga and S. W. Njoka. 1998. Water Hyacinth: An Environmental Disaster in the Winam Gulf of Lake Victoria and its Control, p. 101-105.

- ↑ Gichuki, J., F. Dahdouh Guebas, J. Mugo, C. O. Rabour, L. Triest and F. Dehairs. 2001. Species inventory and the local uses of the plants and fishes of the Lower Sondu Miriu wetland of Lake Victoria, Kenya. Hydrobiologia 458:99-106.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Albright, T. P., Moorhouse, T. G., & McNabb, T. J. (January 01, 2004). The Rise and Fall of Water Hyacinth in Lake Victoria and the Kagera River Basin, 1989-2001. Journal of Aquatic Plant Management, 42, 73-84.

- ↑ Jäger, J., Bohunovsky, L., Radosh, L., & Sustainability Project. (2008). Our planet: How much more can earth take?. London: Haus.

- ↑ Ochiel, G. S., A. M. Mailu, W. Gitonga and S. W. Njoka. 1999. Biological Control of Water Hyacinth on Lake Victoria, Kenya, p. 115-118.

- ↑ Mallya, G. A. 1999. Water hyacinth control in Tanzania, p. 25-29.

- ↑ United Nations Environment Programme., & Belgium. (2006). Africa's lakes: Atlas of our changing environment. Nairobi, Kenya: UNEP.

- ↑ Crisman, T. L., Chapman, Lauren J., Chapman, Colin A., & Kaufman, Les S. (2003). Conservation, ecology, and management of African fresh waters. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- ↑ "Water Hyacinth Re-invades Lake Victoria". Image of the Dat. NASA. February 21, 2007.

- ↑

"Speke, John Hanning". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

"Speke, John Hanning". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900. - ↑ "Kenya, Africa – Lake Victoria in Kenya". Jambo Kenya Network. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ↑ Fred Pearce (February 9, 2006). "Uganda pulls plug on Lake Victoria". New Scientist. 2538: 12.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lake Victoria. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Lake Victoria. |

- Decreasing levels of Lake Victoria Worry East African Countries

- Bibliography on Water Resources and International Law Peace Palace Library

- New Scientist article on Uganda's violation of the agreed curve for hydroelectric water flow.

- Dams Draining Lake Victoria

- Troubled Waters: The Coming Calamity on Lake Victoria multimedia from CLPMag.org

- Specie List of Lake Victoria Basin Cichlids of Lake Victoria and surrounding lakes

- G. D. Hale Carpenter joined the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and took the DM in 1913 with a dissertation on the tsetse fly (Glossina palpalis) and African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness). He published: A Naturalist on Lake Victoria, with an Account of Sleeping Sickness and the Tse-tse Fly (1920). T. F. Unwin Ltd, London; Biodiversity Archive

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v9VJ6cezlnU - A beautiful video of Lake Victoria

Institutions of the East African Community