Vietnam

Coordinates: 16°10′N 107°50′E / 16.167°N 107.833°E

| Socialist Republic of Vietnam Cộng hòa Xã hội chủ nghĩa Việt Nam |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: "Độc lập – Tự do – Hạnh phúc" "Independence – Freedom – Happiness" |

||||||

| Anthem: "Tiến Quân Ca" (English: "Army March") |

||||||

![Location of Vietnam (green)in ASEAN (dark grey) – [Legend]](../I/m/Location_Vietnam_ASEAN.svg.png) |

||||||

| Capital | Hanoi 21°2′N 105°51′E / 21.033°N 105.850°E | |||||

| Largest city | Ho Chi Minh City | |||||

| Official languages | Vietnamese | |||||

| Official scripts | Vietnamese | |||||

| Ethnic groups | ||||||

| Demonym | Vietnamese | |||||

| Government | Unitary Marxist–Leninist one-party socialist state | |||||

| • | President | Trần Đại Quang | ||||

| • | Prime Minister | Nguyễn Xuân Phúc | ||||

| • | Chairwoman of National Assembly | Nguyễn Thị Kim Ngân | ||||

| Legislature | National Assembly | |||||

| Formation | ||||||

| • | Viet Minh declare independence from France | 2 September 1945 | ||||

| • | Fall of Saigon | 30 April 1975 | ||||

| • | Reunification | 2 July 1976[2] | ||||

| • | Current constitution | 28 November 2013[lower-alpha 3] | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| • | Total | 332,698 km2 (65th) 128,565 sq mi |

||||

| • | Water (%) | 6.4[3] | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| • | 2015 estimate | 91,700,000[4] (14th) | ||||

| • | Density | 276.03/km2 (46th) 714.9/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2015 estimate | |||||

| • | Total | $593.509 billion[4] | ||||

| • | Per capita | $6,414[4] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2015 estimate | |||||

| • | Total | $214.750 billion[4] | ||||

| • | Per capita | $2,321[4] | ||||

| Gini (2005–2013) | 35.6[5] medium |

|||||

| HDI (2014) | medium · 116th |

|||||

| Currency | đồng (₫) (VND) | |||||

| Time zone | Indochina Time (UTC+07:00) | |||||

| • | Summer (DST) | No DST (UTC+7) | ||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Calling code | +84 | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | VN | |||||

| Internet TLD | .vn | |||||

Vietnam (UK /ˌvjɛtˈnæm, -ˈnɑːm/, US ![]() i/ˌviːətˈnɑːm, -ˈnæm/;[6] Vietnamese: Việt Nam [viət˨ næm˧]), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV; Vietnamese: Cộng hòa Xã hội chủ nghĩa Việt Nam (

i/ˌviːətˈnɑːm, -ˈnæm/;[6] Vietnamese: Việt Nam [viət˨ næm˧]), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV; Vietnamese: Cộng hòa Xã hội chủ nghĩa Việt Nam (![]() listen)), is the easternmost country on the Indochina Peninsula in Southeast Asia. With an estimated 90.5 million inhabitants as of 2014, it is the world's 14th-most-populous country, and the eighth-most-populous Asian country. Vietnam is bordered by China to the north, Laos to the northwest, Cambodia to the southwest, and Malaysia across the South China Sea to the southeast.[lower-alpha 4] Its capital city has been Hanoi since the reunification of North and South Vietnam in 1975.

listen)), is the easternmost country on the Indochina Peninsula in Southeast Asia. With an estimated 90.5 million inhabitants as of 2014, it is the world's 14th-most-populous country, and the eighth-most-populous Asian country. Vietnam is bordered by China to the north, Laos to the northwest, Cambodia to the southwest, and Malaysia across the South China Sea to the southeast.[lower-alpha 4] Its capital city has been Hanoi since the reunification of North and South Vietnam in 1975.

Vietnam was part of Imperial China for over a millennium, from 111 BC to AD 939. An independent Vietnamese state was formed in 939, following a Vietnamese victory in the Battle of Bạch Đằng River. Successive Vietnamese royal dynasties flourished as the nation expanded geographically and politically into Southeast Asia, until the Indochina Peninsula was colonized by the French in the mid-19th century. Following a Japanese occupation in the 1940s, the Vietnamese fought French rule in the First Indochina War, eventually expelling the French in 1954. Thereafter, Vietnam was divided politically into two rival states, North and South Vietnam. Conflict between the two sides intensified in what is known as the Vietnam War. The war ended with a North Vietnamese victory in 1975.

Vietnam was then unified under a communist government but remained impoverished and politically isolated. In 1986, the government initiated a series of economic and political reforms which began Vietnam's path towards integration into the world economy.[8] By 2000, it had established diplomatic relations with all nations. Since 2000, Vietnam's economic growth rate has been among the highest in the world,[8] and, in 2011, it had the highest Global Growth Generators Index among 11 major economies.[9] Its successful economic reforms resulted in its joining the World Trade Organization in 2007. It is also a historical member of the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie. Vietnam remains one of the world's four remaining one-party socialist states officially espousing communism.

Etymology

The name Việt Nam (Vietnamese pronunciation: [viə̀t naːm]) is a variation of Nam Việt (Chinese: 南越; pinyin: Nányuè; literally Southern Việt), a name that can be traced back to the Triệu Dynasty of the 2nd century BC.[10] The word Việt originated as a shortened form of Bách Việt (Chinese: 百越; pinyin: Bǎiyuè), a word applied to a group of peoples then living in southern China and Vietnam.[11] The form "Vietnam" (越南) is first recorded in the 16th-century oracular poem Sấm Trạng Trình. The name has also been found on 12 steles carved in the 16th and 17th centuries, including one at Bao Lam Pagoda in Haiphong that dates to 1558.[12]

In 1802, Nguyễn Phúc Ánh established the Nguyễn dynasty, and in the second year, he asked the Qing Emperor Jiaqing to confer him the title 'King of Nam Viet/Nanyue'(南越 in Chinese), but the Grand Secretariat of Qing dynasty pointed out that the name Nam Viet/Nanyue includes regions of Guangxi and Guangdong in China, and 'Nguyễn Phúc Ánh only has Annam, which is simply the area of our old Jiaozhi (交趾), how can they be called Nam Viet/Nanyue?' Then, as recorded, '(Qing dynasty) rewarded Yuenan/Vietnam(越南) as their nation's name, ..., to also show that they are below the region of Baiyue/Bach Viet'.[13]

Between 1804 and 1813, the name was used officially by Emperor Gia Long.[lower-alpha 5] It was revived in the early 20th century by Phan Bội Châu's History of the Loss of Vietnam, and later by the Vietnamese Nationalist Party.[14] The country was usually called Annam until 1945, when both the imperial government in Huế and the Viet Minh government in Hanoi adopted Việt Nam.[15]

History

Prehistory and ancient history

Archaeological excavations have revealed the existence of humans in what is now Vietnam as early as the Paleolithic age. Homo erectus fossils dating to around 500,000 BC have been found in caves in Lạng Sơn and Nghệ An provinces in northern Vietnam.[16] The oldest Homo sapiens fossils from mainland Southeast Asia are of Middle Pleistocene provenance, and include isolated tooth fragments from Tham Om and Hang Hum.[17] Teeth attributed to Homo sapiens from the Late Pleistocene have also been found at Dong Can,[18] and from the Early Holocene at Mai Da Dieu,[18] Lang Gao[19] and Lang Cuom.[20]

By about 1000 BC, the development of wet-rice cultivation and bronze casting in the Ma River and Red River floodplains led to the flourishing of the Đông Sơn culture, notable for its elaborate bronze drums. At this time, the early Vietnamese kingdoms of Văn Lang and Âu Lạc appeared, and the culture's influence spread to other parts of Southeast Asia, including Maritime Southeast Asia, throughout the first millennium BC.[21][22][23]

Dynastic Vietnam

The Hồng Bàng dynasty of the Hùng kings is considered the first Vietnamese state, known in Vietnamese as Văn Lang. In 257 BC, the last Hùng king was defeated by Thục Phán, who consolidated the Lạc Việt and Âu Việt tribes to form the Âu Lạc, proclaiming himself An Dương Vương. In 207 BC, a Chinese general named Zhao Tuo defeated An Dương Vương and consolidated Âu Lạc into Nanyue. However, Nanyue was itself incorporated into the empire of the Chinese Han dynasty in 111 BC after the Han–Nanyue War.

For the next thousand years, what is now northern Vietnam remained mostly under Chinese rule.[24] Early independence movements, such as those of the Trưng Sisters and Lady Triệu, were only temporarily successful, though the region gained a longer period of independence as Vạn Xuân under the Anterior Lý dynasty between AD 544 and 602.[25] By the early 10th century, Vietnam had gained autonomy, but not sovereignty, under the Khúc family.

In AD 938, the Vietnamese lord Ngô Quyền defeated the forces of the Chinese Southern Han state at Bạch Đằng River and achieved full independence for Vietnam after a millennium of Chinese domination.[26] Renamed as Đại Việt (Great Viet), the nation enjoyed a golden era under the Lý and Trần dynasties. During the rule of the Trần Dynasty, Đại Việt repelled three Mongol invasions.[27] Meanwhile, Buddhism flourished and became the state religion.

Following the 1406–7 Ming–Hồ War which overthrew the Hồ dynasty, Vietnamese independence was briefly interrupted by the Chinese Ming dynasty, but was restored by Lê Lợi, the founder of the Lê dynasty. The Vietnamese dynasties reached their zenith in the Lê dynasty of the 15th century, especially during the reign of Emperor Lê Thánh Tông (1460–1497). Between the 11th and 18th centuries, Vietnam expanded southward in a process known as nam tiến ("southward expansion"),[28] eventually conquering the kingdom of Champa and part of the Khmer Empire.[29][30]

From the 16th century onwards, civil strife and frequent political infighting engulfed much of Vietnam. First, the Chinese-supported Mạc dynasty challenged the Lê dynasty's power. After the Mạc dynasty was defeated, the Lê dynasty was nominally reinstalled, but actual power was divided between the northern Trịnh lords and the southern Nguyễn lords, who engaged in a civil war for more than four decades before a truce was called in the 1670s. During this time, the Nguyễn expanded southern Vietnam into the Mekong Delta, annexing the Central Highlands and the Khmer lands in the Mekong Delta.

The division of the country ended a century later when the Tây Sơn brothers established a new dynasty. However, their rule did not last long, and they were defeated by the remnants of the Nguyễn lords, led by Nguyễn Ánh and aided by the French.[31] Nguyễn Ánh unified Vietnam, and established the Nguyễn dynasty, ruling under the name Gia Long.

1862–1945: French Indochina

.jpg)

Vietnam's independence was gradually eroded by France – aided by large Catholic militias – in a series of military conquests between 1859 and 1885. In 1862, the southern third of the country became the French colony of Cochinchina. By 1884, the entire country had come under French rule, with the Central and Northern parts of Vietnam separated in the two protectorates of Annam and Tonkin. The three Vietnameses entities were formally integrated into the union of French Indochina in 1887. The French administration imposed significant political and cultural changes on Vietnamese society. A Western-style system of modern education was developed, and Roman Catholicism was propagated widely. Most French settlers in Indochina were concentrated in Cochinchina, particularly in the region of Saigon.[32] The royalist Cần Vương movement rebelled against French rule and was defeated in the 1890s after a decade of resistance. Guerrillas of the Cần Vương movement murdered around a third of Vietnam's Christian population during this period.[33]

Developing a plantation economy to promote the export of tobacco, indigo, tea and coffee, the French largely ignored increasing calls for Vietnamese self-government and civil rights. A nationalist political movement soon emerged, with leaders such as Phan Bội Châu, Phan Chu Trinh, Phan Đình Phùng, Emperor Hàm Nghi and Ho Chi Minh fighting or calling for independence. However, the 1930 Yên Bái mutiny of the Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng was suppressed easily.[34] The French maintained full control of their colonies until World War II, when the war in the Pacific led to the Japanese invasion of French Indochina in 1940. Afterwards, the Japanese Empire was allowed to station its troops in Vietnam while permitting the pro-Vichy French colonial administration to continue. Japan exploited Vietnam's natural resources to support its military campaigns, culminating in a full-scale takeover of the country in March 1945 and the Vietnamese Famine of 1945, which caused up to two million deaths.[35]

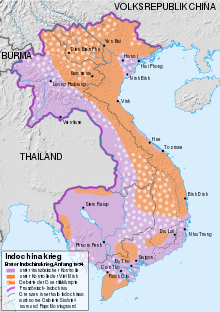

1946–54: First Indochina War

Legend:

In 1941, the Viet Minh – a communist and nationalist liberation movement – emerged under the Marxist–Leninist revolutionary Ho Chi Minh, who sought independence for Vietnam from France and the end of the Japanese occupation. Following the military defeat of Japan and the fall of its puppet Empire of Vietnam in August 1945, the Viet Minh occupied Hanoi and proclaimed a provisional government, which asserted national independence on 2 September. In the same year, the Provisional Government of the French Republic sent the French Far East Expeditionary Corps to restore colonial rule, and the Viet Minh began a guerrilla campaign against the French in late 1946.[36] The resulting First Indochina War lasted until July 1954.[37]

The defeat of French and Vietnamese loyalists in the 1954 Battle of Dien Bien Phu allowed Ho Chi Minh to negotiate a ceasefire from a favorable position at the subsequent Geneva Conference. The colonial administration was ended and French Indochina was dissolved under the Geneva Accords of 1954, which separated the loyalist forces from the communists at the 17th parallel north with the Vietnamese Demilitarized Zone.[lower-alpha 6] Two states formed after the partition – Ho Chi Minh's Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the north and Emperor Bảo Đại's State of Vietnam in the south. A 300-day period of free movement was permitted, during which almost a million northerners, mainly Catholics, moved south, fearing persecution by the communists.[41]

The partition of Vietnam was not intended to be permanent by the Geneva Accords, which stipulated that Vietnam would be reunited after elections in 1956.[42] However, in 1955, the State of Vietnam's Prime Minister, Ngô Đình Diệm, toppled Bảo Đại in a fraudulent referendum organised by his brother Ngô Đình Nhu, and proclaimed himself president of the Republic of Vietnam.[43]

1954–1975: Vietnam War

The pro-Hanoi Viet Cong began a guerrilla campaign in the late 1950s to overthrow Diệm's government.[44] Between 1953 and 1956, the North Vietnamese government instituted various agrarian reforms, including "rent reduction" and "land reform," which resulted in significant political oppression. During the land reform, testimony from North Vietnamese witnesses suggested a ratio of one execution for every 160 village residents, which extrapolated nationwide would indicate nearly 100,000 executions. Because the campaign was concentrated mainly in the Red River Delta area, a lower estimate of 50,000 executions became widely accepted by scholars at the time.[45][46][47][48] However, declassified documents from the Vietnamese and Hungarian archives indicate that the number of executions was much lower than reported at the time, although likely greater than 13,500.[49] In 1960 and 1962, the Soviet Union and North Vietnam signed treaties providing for further Soviet military support. In the South, Diệm countered North Vietnamese subversion (including the assassination of over 450 South Vietnamese officials in 1956) by detaining tens of thousands of suspected communists in "political reeducation centers." This was a ruthless program that incarcerated many non-communists, although it was also successful at curtailing communist activity in the country, if only for a time. The North Vietnamese government claimed that 2,148 individuals were killed in the process by November 1957.[50] In 1960 and 1962, the Soviet Union and North Vietnam signed treaties providing for further Soviet military support.

In 1963, Buddhist discontent with Diệm's regime erupted into mass demonstrations, leading to a violent government crackdown.[51] This led to the collapse of Diệm's relationship with the United States, and ultimately to the 1963 coup in which Diệm and Nhu were assassinated.[52] The Diệm era was followed by more than a dozen successive military governments, before the pairing of Air Marshal Nguyễn Cao Kỳ and General Nguyễn Văn Thiệu took control in mid-1965. Thieu gradually outmaneuvered Ky and cemented his grip on power in fraudulent elections in 1967 and 1971.[53] Under this political instability, the communists began to gain ground.

To support South Vietnam's struggle against the communist insurgency, the United States began increasing its contribution of military advisers, using the 1964 Tonkin Gulf incident as a pretext for such intervention. US forces became involved in ground combat operations in 1965, and at their peak they numbered more than 500,000.[54][55] The US also engaged in a sustained aerial bombing campaign. Meanwhile, China and the Soviet Union provided North Vietnam with significant material aid and 15,000 combat advisers.[56][57] Communist forces supplying the Viet Cong carried supplies along the Ho Chi Minh trail, which passed through Laos.[58]

The communists attacked South Vietnamese targets during the 1968 Tet Offensive. Although the campaign failed militarily, it shocked the American establishment, and turned US public opinion against the war.[59][60] During the offensive, communist troops massacred over 3,000 civilians at Hue.[61] Facing an increasing casualty count, rising domestic opposition to the war, and growing international condemnation, the US began withdrawing from ground combat roles in the early 1970s. This process also entailed an unsuccessful effort to strengthen and stabilize South Vietnam.[62]

Following the Paris Peace Accords of 27 January 1973, all American combat troops were withdrawn by 29 March 1973. In December 1974, North Vietnam captured the province of Phước Long and started a full-scale offensive, culminating in the Fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975.[63] South Vietnam was briefly ruled by a provisional government while under military occupation by North Vietnam. On 2 July 1976, North and South Vietnam were merged to form the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.[2] The war left Vietnam devastated, with the total death toll standing at between 800,000 and 3.1 million.[35][64][65]

1976–present: reunification and reforms

In the aftermath of the war, under Lê Duẩn's administration, there were no mass executions of South Vietnamese who had collaborated with the U.S. or the Saigon government, confounding Western fears.[66] However, up to 300,000 South Vietnamese were sent to reeducation camps, where many endured torture, starvation, and disease while being forced to perform hard labor.[67] The government embarked on a mass campaign of collectivization of farms and factories.[68] This caused economic chaos and resulted in triple-digit inflation, while national reconstruction efforts progressed slowly. In 1978, the Vietnamese military invaded Cambodia to remove from power the Khmer Rouge, who had been attacking Vietnamese border villages.[69] Vietnam was victorious, installing a government in Cambodia which ruled until 1989.[70] This action worsened relations with the Chinese, who launched a brief incursion into northern Vietnam in 1979.[71] This conflict caused Vietnam to rely even more heavily on Soviet economic and military aid.

At the Sixth National Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam in December 1986, reformist politicians replaced the "old guard" government with new leadership.[72][73] The reformers were led by 71-year-old Nguyễn Văn Linh, who became the party's new general secretary.[72][73] Linh and the reformers implemented a series of free-market reforms – known as Đổi Mới ("Renovation") – which carefully managed the transition from a planned economy to a "socialist-oriented market economy".[74][75]

Though the authority of the state remained unchallenged under Đổi Mới, the government encouraged private ownership of farms and factories, economic deregulation and foreign investment, while maintaining control over strategic industries.[75] The Vietnamese economy subsequently achieved strong growth in agricultural and industrial production, construction, exports and foreign investment. However, these reforms have also caused a rise in income inequality and gender disparities.[76][77][78]

Government and politics

.jpg)

The Socialist Republic of Vietnam, along with China, Cuba, and Laos, is one of the world's four remaining one-party socialist states officially espousing communism. Its current state constitution, 2013 Constitution, asserts the central role of the Communist Party of Vietnam in all organs of government, politics and society. The General Secretary of the Communist Party performs numerous key administrative and executive functions, controlling the party's national organization and state appointments, as well as setting policy. Only political organizations affiliated with or endorsed by the Communist Party are permitted to contest elections in Vietnam. These include the Vietnamese Fatherland Front and worker and trade unionist parties. Although the state remains officially committed to socialism as its defining creed, its economic policies have grown increasingly capitalist,[79] with The Economist characterizing its leadership as "ardently capitalist communists".[80]

Legislature

The National Assembly of Vietnam is the unicameral legislature of the state, composed of 498 members. Headed by a Chairman, it is superior to both the executive and judicial branches, with all government ministers being appointed from members of the National Assembly.

Executive

The President of Vietnam is the titular head of state and the nominal commander-in-chief of the military, serving as the Chairman of the Council of Supreme Defense and Security. The Prime Minister of Vietnam is the head of government, presiding over a council of ministers composed of three deputy prime ministers and the heads of 26 ministries and commissions.

Judiciary

The Supreme People's Court of Vietnam, headed by a Chief Justice, is the country's highest court of appeal, though it is also answerable to the National Assembly. Beneath the Supreme People's Court stand the provincial municipal courts and numerous local courts. Military courts possess special jurisdiction in matters of national security. Vietnam maintains the death penalty for numerous offences; as of February 2014, there are around 700 inmates on death row in Vietnam.[81]

Military

The Vietnam People's Armed Forces consists of the Vietnam People's Army, the Vietnam People's Public Security and the Vietnam Civil Defense Force. The Vietnam People's Army (VPA) is the official name for the active military services of Vietnam, and is subdivided into the Vietnam People's Ground Forces, the Vietnam People's Navy, the Vietnam People's Air Force, the Vietnam Border Defense Force and the Vietnam Coast Guard. The VPA has an active manpower of around 450,000, but its total strength, including paramilitary forces, may be as high as 5,000,000.[82] In 2011, Vietnam's military expenditure totalled approximately US$2.48 billion, equivalent to around 2.5% of its 2010 GDP.[83]

International relations

Throughout its history, Vietnam's key foreign relationship has been with its largest neighbour and one-time imperial master, China. Vietnam's sovereign principles and insistence on cultural independence have been laid down in numerous documents over the centuries, such as the 11th-century patriotic poem Nam quốc sơn hà and the 1428 proclamation of independence Bình Ngô đại cáo. Though China and Vietnam are now formally at peace, significant territorial tensions remain between the two countries.[84]

Currently, the formal mission statement of Vietnamese foreign policy is to: "Implement consistently the foreign policy line of independence, self-reliance, peace, cooperation and development; the foreign policy of openness and diversification and multi-lateralization of international relations. Proactively and actively engage in international economic integration while expanding international cooperation in other fields."[85] Vietnam furthermore declares itself to be "a friend and reliable partner of all countries in the international community, actively taking part in international and regional cooperation processes."[85]

By December 2007, Vietnam had established diplomatic relations with 172 countries, including the United States, which normalized relations in 1995.[86][87] Vietnam holds membership of 63 international organizations, including the United Nations, ASEAN, NAM, Francophonie and WTO. It also maintains relations with over 650 non-government organizations.[88]

In May 2016, President Obama further normalized relations with Vietnam after he announced the lifting of an arms embargo on sales of lethal arms to Vietnam.[89]

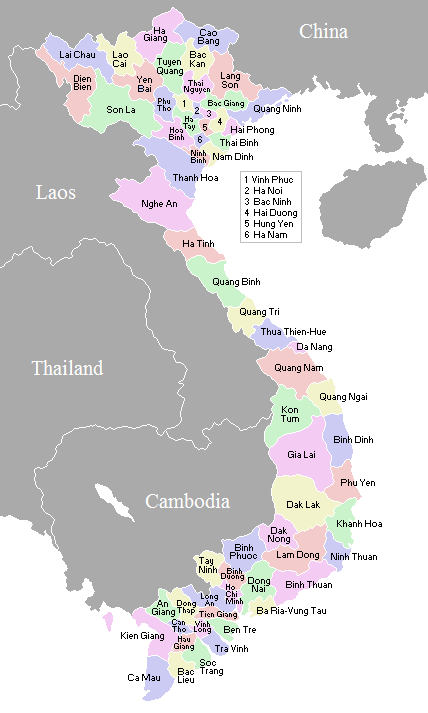

Administrative subdivisions

Vietnam is divided into 58 provinces (Vietnamese: tỉnh, from the Chinese 省, shěng). There are also five municipalities (thành phố trực thuộc trung ương), which are administratively on the same level as provinces.

|

Bắc Ninh |

Bắc Giang |

|

Hà Tĩnh |

|

|

Bình Định |

Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu |

An Giang |

The provinces are subdivided into provincial municipalities (thành phố trực thuộc tỉnh), townships (thị xã) and counties (huyện), which are in turn subdivided into towns (thị trấn) or communes (xã). The centrally controlled municipalities are subdivided into districts (quận) and counties, which are further subdivided into wards (phường).

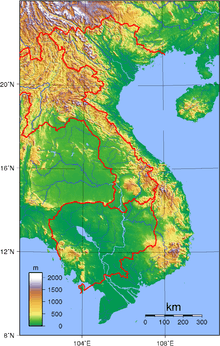

Geography

Vietnam is located on the eastern Indochina Peninsula between the latitudes 8° and 24°N, and the longitudes 102° and 110°E. It covers a total area of approximately 331,210 km2 (127,881 sq mi),[3] making it almost the size of Germany. The combined length of the country's land boundaries is 4,639 km (2,883 mi), and its coastline is 3,444 km (2,140 mi) long.[3] At its narrowest point in the central Quảng Bình Province, the country is as little as 50 kilometres (31 mi) across, though it widens to around 600 kilometres (370 mi) in the north. Vietnam's land is mostly hilly and densely forested, with level land covering no more than 20%. Mountains account for 40% of the country's land area, and tropical forests cover around 42%.

The northern part of the country consists mostly of highlands and the Red River Delta. Phan Xi Păng, located in Lào Cai Province, is the highest mountain in Vietnam, standing 3,143 m (10,312 ft) high. Southern Vietnam is divided into coastal lowlands, the mountains of the Annamite Range, and extensive forests. Comprising five relatively flat plateaus of basalt soil, the highlands account for 16% of the country's arable land and 22% of its total forested land. The soil in much of southern Vietnam is relatively poor in nutrients.

The Red River Delta, a flat, roughly triangular region covering 15,000 km2 (5,792 sq mi),[90] is smaller but more intensely developed and more densely populated than the Mekong River Delta. Once an inlet of the Gulf of Tonkin, it has been filled in over the millennia by riverine alluvial deposits. The delta, covering about 40,000 km2 (15,444 sq mi), is a low-level plain no more than 3 meters (9.8 ft) above sea level at any point. It is criss-crossed by a maze of rivers and canals, which carry so much sediment that the delta advances 60 to 80 meters (196.9 to 262.5 ft) into the sea every year.

Panoramic view

Climate

Because of differences in latitude and the marked variety in topographical relief, the climate tends to vary considerably from place to place. During the winter or dry season, extending roughly from November to April, the monsoon winds usually blow from the northeast along the Chinese coast and across the Gulf of Tonkin, picking up considerable moisture. Consequently, the winter season in most parts of the country is dry only by comparison with the rainy or summer season. The average annual temperature is generally higher in the plains than in the mountains, and higher in the south than in the north. Temperatures vary less in the southern plains around Ho Chi Minh City and the Mekong Delta, ranging between 21 and 28 °C (69.8 and 82.4 °F) over the course of the year. Seasonal variations in the mountains and plateaus and in the north are much more dramatic, with temperatures varying from 5 °C (41.0 °F) in December and January to 37 °C (98.6 °F) in July and August.

Ecology and biodiversity

Vietnam has two World Natural Heritage Sites – Hạ Long Bay and Phong Nha-Kẻ Bàng National Park – and six biosphere reserves, including Cần Giờ Mangrove Forest, Cát Tiên, Cát Bà, Kiên Giang, the Red River Delta, and Western Nghệ An.

Vietnam lies in the Indomalaya ecozone. According to the 2005 National Environmental Present Condition Report.[91] Vietnam is one of twenty-five countries considered to possess a uniquely high level of biodiversity. It is ranked 16th worldwide in biological diversity, being home to approximately 16% of the world's species. 15,986 species of flora have been identified in the country, of which 10% are endemic, while Vietnam's fauna include 307 nematode species, 200 oligochaeta, 145 acarina, 113 springtails, 7,750 insects, 260 reptiles, 120 amphibians, 840 birds and 310 mammals, of which 100 birds and 78 mammals are endemic.[91]

Vietnam is furthermore home to 1,438 species of freshwater microalgae, constituting 9.6% of all microalgae species, as well as 794 aquatic invertebrates and 2,458 species of sea fish.[91] In recent years, 13 genera, 222 species, and 30 taxa of flora have been newly described in Vietnam.[91] Six new mammal species, including the saola, giant muntjac and Tonkin snub-nosed monkey have also been discovered, along with one new bird species, the endangered Edwards's pheasant.[92] In the late 1980s, a small population of Javan rhinoceros was found in Cát Tiên National Park. However, the last individual of the species in Vietnam was reportedly shot in 2010.[93]

In agricultural genetic diversity, Vietnam is one of the world's twelve original cultivar centers. The Vietnam National Cultivar Gene Bank preserves 12,300 cultivars of 115 species.[91] The Vietnamese government spent US$49.07 million on the preservation of biodiversity in 2004 alone, and has established 126 conservation areas, including 28 national parks.[91]

Economy

In 2012, Vietnam's nominal GDP reached US$138 billion, with a nominal GDP per capita of $1,527.[4] According to a December 2005 forecast by Goldman Sachs, the Vietnamese economy will become the world's 21st-largest by 2025, with an estimated nominal GDP of $436 billion and a nominal GDP per capita of $4,357.[94] According to a 2008 forecast by PricewaterhouseCoopers, Vietnam may be the fastest-growing of the world's emerging economies by 2025, with a potential growth rate of almost 10% per annum in real dollar terms.[95] In 2012, HSBC predicted that Vietnam's total GDP would surpass those of Norway, Singapore and Portugal by 2050.[96]

Vietnam has been for much of its history a predominantly agricultural civilization based on wet rice cultivation. There is also an industry for bauxite mining in Vietnam, an important material for the production of aluminum. The Vietnamese economy is shaped primarily by the Vietnamese Communist Party in Five Year Plans made through the plenary sessions of the Central Committee and national congresses.

The collectivization of farms, factories and economic capital is a part of this central planning, with millions of people working in government programs. Vietnam's economy has been plagued with inefficiency and corruption in state programs, poor quality and underproduction, and restrictions on economic activity. It also suffered from the post-war trade embargo instituted by the United States and most of Europe. These problems were compounded by the erosion of the Soviet bloc, which included Vietnam's main trading partners, in the late 1980s.

In 1986, the Sixth National Congress of the Communist Party introduced socialist-oriented market economic reforms as part of the Đổi Mới reform program. Private ownership was encouraged in industries, commerce and agriculture.[97] Thanks largely to these reforms, Vietnam achieved around 8% annual GDP growth between 1990 and 1997, and the economy continued to grow at an annual rate of around 7% from 2000 to 2005, making Vietnam one of the world's fastest growing economies. Growth remained strong even in the face of the late-2000s global recession, holding at 6.8% in 2010, but Vietnam's year-on-year inflation rate hit 11.8% in December 2010, according to a GSO estimate. The Vietnamese dong was devalued three times in 2010 alone.[98]

Manufacturing, information technology and high-tech industries now form a large and fast-growing part of the national economy. Though Vietnam is a relative newcomer to the oil industry, it is currently the third-largest oil producer in Southeast Asia, with a total 2011 output of 318,000 barrels per day (50,600 m3/d).[99] In 2010, Vietnam was ranked as the 8th largest crude petroleum producers in the Asia and Pacific region.[100] Like its Chinese neighbours, Vietnam continues to make use of centrally planned economic five-year plans.

Deep poverty, defined as the percentage of the population living on less than $1 per day, has declined significantly in Vietnam, and the relative poverty rate is now less than that of China, India, and the Philippines.[101] This decline in the poverty rate can be attributed to equitable economic policies aimed at improving living standards and preventing the rise of inequality; these policies have included egalitarian land distribution during the initial stages of the Đổi Mới program, investment in poorer remote areas, and subsidising of education and healthcare.[102] According to the IMF, the unemployment rate in Vietnam stood at 4.46% in 2012.[4]

Trade

Since the early 2000s, Vietnam has applied sequenced trade liberalisation, a two-track approach opening some sectors of the economy to international markets while protecting others.[102][103] In July 2006, Vietnam updated its intellectual property legislation to comply with TRIPS, and it became a member of the WTO on 11 January 2007. Vietnam is now one of Asia's most open economies: two-way trade was valued at around 160% of GDP in 2006, more than twice the contemporary ratio for China and over four times the ratio for India.[104] Vietnam's chief trading partners include China, Japan, Australia, the ASEAN countries, the United States and Western Europe.

Vietnam's Customs office reported in July 2013 that the total value of international merchandise trade for the first half of 2013 was US$124 billion, which was 15.7% higher than the same period in 2012. Mobile phones and their parts were both imported and exported in large numbers, while in the natural resources market, crude oil was a top-ranking export and high levels of iron and steel were imported during this period. The U.S. was the country that purchased the highest amount of Vietnam's exports, while Chinese goods were the most popular Vietnamese import.[105]

As a result of several land reform measures, Vietnam has become a major exporter of agricultural products. It is now the world's largest producer of cashew nuts, with a one-third global share; the largest producer of black pepper, accounting for one-third of the world's market; and the second-largest rice exporter in the world, after Thailand. Vietnam is the world's second largest exporter of coffee.[106] Vietnam has the highest proportion of land use for permanent crops – 6.93% – of any nation in the Greater Mekong Subregion. Other primary exports include tea, rubber, and fishery products. However, agriculture's share of Vietnam's GDP has fallen in recent decades, declining from 42% in 1989 to 20% in 2006, as production in other sectors of the economy has risen.

In 2014 Vietnam negotiated a free trade agreement with the European Union, giving the country access to the EU's Generalized System of Preferences. This provides preferential access to European markets for developing countries through reduced tariffs.[107]

Science and technology

Vietnamese scholars developed many academic fields during the dynastic era, most notably social sciences and the humanities. Vietnam has a millennium-deep legacy of analytical histories, such as the Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư of Ngô Sĩ Liên. Vietnamese monks led by the abdicated Emperor Trần Nhân Tông developed the Trúc Lâm Zen branch of philosophy in the 13th century. Arithmetics and geometry have been widely taught in Vietnam since the 15th century, using the textbook Đại thành toán pháp by Lương Thế Vinh as a basis. Lương Thế Vinh introduced Vietnam to the notion of zero, while Mạc Hiển Tích used the term số ẩn (en: "unknown/secret/hidden number") to refer to negative numbers. Vietnamese scholars furthermore produced numerous encyclopedias, such as Lê Quý Đôn's Vân đài loại ngữ.

In recent times, Vietnamese scientists have made many significant contributions in various fields of study, most notably in mathematics. Hoàng Tụy pioneered the applied mathematics field of global optimization in the 20th century, while Ngô Bảo Châu won the 2010 Fields Medal for his proof of fundamental lemma in the theory of automorphic forms. Vietnam is currently working to develop an indigenous space program, and plans to construct the US$600 million Vietnam Space Center by 2018.[108] Vietnam has also made significant advances in the development of robots, such as the TOPIO humanoid model.[109] In 2010, Vietnam's total state spending on science and technology equalled around 0.45% of its GDP.[110]

Transport

Much of Vietnam's modern transport network was originally developed under French rule to facilitate the transportation of raw materials, and was reconstructed and extensively modernized following the Vietnam War.

Air

Vietnam operates 21 major civil airports, including three international gateways: Noi Bai in Hanoi, Da Nang International Airport in Da Nang, and Tan Son Nhat in Ho Chi Minh City. Tan Son Nhat is the nation's largest airport, handling 75% of international passenger traffic. According to a state-approved plan, Vietnam will have 10 international airports by 2015 – besides the aforementioned three, these include Vinh International Airport, Phu Bai International Airport, Cam Ranh International Airport, Phu Quoc International Airport, Cat Bi International Airport, Cần Thơ International Airport and Long Thanh International Airport. The planned Long Thanh International Airport will have an annual service capacity of 100 million passengers once it becomes fully operational in 2020.

Vietnam Airlines, the state-owned national airline, maintains a fleet of 69 passenger aircraft,[111][112] and aims to operate 150 by 2020. Several private airlines are also in operation in Vietnam, including Air Mekong, Jetstar Pacific Airlines, VASCO and VietJet Air.

Road

Vietnam's road system includes national roads administered at the central level, provincial roads managed at the provincial level, district roads managed at the district level, urban roads managed by cities and towns, and commune roads managed at the commune level. Bicycles, motor scooters and motorcycles remain the most popular forms of road transport in Vietnam's urban areas, although the number of privately owned automobiles is also on the rise, especially in the larger cities. Public buses operated by private companies are the main mode of long-distance travel for much of the population.

Road safety is a serious issue in Vietnam – on average, 30 people are killed in traffic accidents every day.[113] Traffic congestion is a growing problem in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, as the cities' roads struggle to cope with the boom in automobile use.

Rail

Vietnam's primary cross-country rail service is the Reunification Express, which runs from Ho Chi Minh City to Hanoi, covering a distance of nearly 2,000 kilometres. From Hanoi, railway lines branch out to the northeast, north and west; the eastbound line runs from Hanoi to Hạ Long Bay, the northbound line from Hanoi to Thái Nguyên, and the northeast line from Hanoi to Lào Cai.

In 2009, Vietnam and Japan signed a deal to build a high-speed railway using Japanese technology; numerous Vietnamese engineers were later sent to Japan to receive training in the operation and maintenance of high-speed trains. The railway will be a 1,630-km-long[114] express route, serving a total of 26 stations, including Hanoi and the Thu Thiem terminus in Ho Chi Minh City.[115] Using Japan's Shinkansen technology,[116] the line will support trains travelling at a maximum speed of 360 kilometres (220 mi) per hour. The high-speed lines linking Hanoi to Vinh, Nha Trang and Ho Chi Minh City will be laid by 2015. From 2015 to 2020, construction will begin on the routes between Vinh and Nha Trang and between Hanoi and the northern provinces of Lào Cai and Lạng Sơn.

Water

As a coastal country, Vietnam has many major sea ports, including Cam Ranh, Da Nang, Hai Phong, Ho Chi Minh City, Hong Gai, Qui Nhơn, Vũng Tàu and Nha Trang. Further inland, the country's extensive network of rivers play a key role in rural transportation, with over 17,700 kilometres (11,000 mi) of navigable waterways carrying ferries, barges and water taxis.[117][118]

In addition, the Mekong Delta and Red River Delta are vital to Vietnam's social and economic welfare – most of the country's population lives along or near these river deltas, and the major cities of Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi are situated near the Mekong and Red River deltas, respectively. Further out in the South China Sea, Vietnam currently controls the majority of the disputed Spratly Islands, which are the source of longstanding disagreements with China and other nearby nations.[119]

Water supply and sanitation

Water supply and sanitation in Vietnam is characterized by challenges and achievements. Among the achievements is a substantial increase in access to water supply and sanitation between 1990 and 2010, nearly universal metering, and increased investment in wastewater treatment since 2007. Among the challenges are continued widespread water pollution, poor service quality, low access to improved sanitation in rural areas, poor sustainability of rural water systems, insufficient cost recovery for urban sanitation, and the declining availability of foreign grant and soft loan funding as the Vietnamese economy grows and donors shift to loan financing. The government also promotes increased cost recovery through tariff revenues and has created autonomous water utilities at the provincial level, but the policy has had mixed success as tariff levels remain low and some utilities have engaged in activities outside their mandate.

Demographics

As of 2014, the population of Vietnam as standing at approximately 90.7 million people. The population had grown significantly from the 1979 census, which showed the total population of reunified Vietnam to be 52.7 million.[120] In 2012, the country's population was estimated at approximately 90.3 million.[4] Currently, the total fertility rate of Vietnam is 1.8 (births per woman),[121] which is largely due to the government's family planning policy, the two-child policy.

Ethnicity

According to the 2009 census, the dominant Viet or Kinh ethnic group constituted nearly 73.6 million people, or 85.8% of the population. The Kinh population is concentrated mainly in the alluvial deltas and coastal plains of the country. A largely homogeneous social and ethnic group, the Kinh possess significant political and economic influence over the country. However, Vietnam is also home to 54 ethnic minority groups, including the Hmong, Dao, Tay, Thai, and Nùng. Many ethnic minorities – such as the Muong, who are closely related to the Kinh – dwell in the highlands, which cover two-thirds of Vietnam's territory. Before the Vietnam War, the population of the Central Highlands was almost exclusively Degar (including over 40 tribal groups); however, Ngô Đình Diệm's South Vietnamese government enacted a program of resettling Kinh in indigenous areas.[122] The Hoa (ethnic Chinese)[123] and Khmer Krom people are mainly lowlanders. As Sino-Vietnamese relations soured in 1978 and 1979, some 450,000 Hoa left Vietnam.[124]

| | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||||||

| Hồ Chí Minh City  Hà Nội |

1 | Hồ Chí Minh City | Municipalities of Vietnam | 8,244,400 |  Hải Phòng  Cần Thơ | ||||

| 2 | Hà Nội | Municipalities of Vietnam | 7,379,300 | ||||||

| 3 | Hải Phòng | Municipalities of Vietnam | 1,946,000 | ||||||

| 4 | Cần Thơ | Municipalities of Vietnam | 1,238,300 | ||||||

| 5 | Biên Hòa | Đồng Nai | 1,104,495 | ||||||

| 6 | Đà Nẵng | Municipalities of Vietnam | 1,007,700 | ||||||

| 7 | Nha Trang | Khánh Hòa | 393,218 | ||||||

| 8 | Buôn Ma Thuột | Đắk Lắk | 350,000 | ||||||

| 9 | Huế | Thừa Thiên-Huế | 337,554 | ||||||

| 10 | Vinh | Nghệ An | 330,000 | ||||||

Languages

The official national language of Vietnam is Vietnamese (Tiếng Việt), a tonal Mon–Khmer language which is spoken by the majority of the population. In its early history, Vietnamese writing used Chinese characters. In the 13th century, the Vietnamese developed their own set of characters, referred to as Chữ nôm. The folk epic Truyện Kiều ("The Tale of Kieu", originally known as Đoạn trường tân thanh ) by Nguyễn Du was written in Chữ nôm. Quốc ngữ, the romanized Vietnamese alphabet used for spoken Vietnamese, was developed in the 17th century by the Jesuit Alexandre de Rhodes and several other Catholic missionaries.[125] Quốc ngữ became widely popular and brought literacy to the Vietnamese masses during the French colonial period.[125]

Vietnam's minority groups speak a variety of languages, including Tày, Mường, Cham, Khmer, Chinese, Nùng, and H'Mông. The Montagnard peoples of the Central Highlands also speak a number of distinct languages.[126] A number of sign languages have developed in the cities.

The French language, a legacy of colonial rule, is spoken by many educated Vietnamese as a second language, especially among the older generation and those educated in the former South Vietnam, where it was a principal language in administration, education and commerce; Vietnam remains a full member of the Francophonie, and education has revived some interest in the language.[127][128] Russian – and to a much lesser extent German, Czech and Polish – are known among some Vietnamese whose families had ties with the Soviet bloc during the Cold War.[129] In recent years, as Vietnam's contacts with Western nations have increased, English has become more popular as a second language. The study of English is now obligatory in most schools, either alongside or in many cases, replacing French.[129][130] Japanese and Korean have also grown in popularity as Vietnam's links with other East Asian nations have strengthened.

Religion

According to an analysis by the Pew Research Center, in 2010 about 45.3% of the Vietnamese adhere to indigenous religions, 16.4% to Buddhism, 8.2% to Christianity, 0.4% to other faiths, and 29.6% of the population isn't religious.[131]

According to the General Statistics Office of Vietnam's report for 1 April 2009, 6.8 million (or 7.9% of the total population) are practicing Buddhists, 5.7 million (6.6%) are Catholics, 1.4 million (1.7%) are adherents of Hòa Hảo, 0.8 million (0.9%) practise Caodaism, and 0.7 million (0.9%) are Protestants. In total, 15,651,467 Vietnamese (18.2%) are formally registered in a religion.[132] According to the 2009 census, while over 10 million people have taken refuge in the Three Jewels of Buddhism,[133][134] the vast majority of Vietnamese people practice ancestor worship in some form. According to a 2007 report, 81% of the Vietnamese people do not believe in God.[135]

About 8% of the population are Christians, totalling around six million Roman Catholics and fewer than one million Protestants. Christianity was first introduced to Vietnam by Portuguese and Dutch traders in the 16th and 17th centuries, and was further propagated by French missionaries in the 19th and 20th centuries, and to a lesser extent, by American Protestant missionaries during the Vietnam War, largely among the Montagnards of South Vietnam.

The largest Protestant churches are the Evangelical Church of Vietnam and the Montagnard Evangelical Church. Two-thirds of Vietnam's Protestants are reportedly members of ethnic minorities.[136] Although a small religious minority, Protestantism is claimed to be the country's fastest-growing religion, expanding at a rate of 600% in the previous decade.[137]

The Vietnamese government is widely seen as suspicious of Roman Catholicism. This mistrust originated during the 19th century, when some Catholics collaborated with the French colonists in conquering and ruling the country and in helping French attempts to install Catholic emperors, such as in the Lê Văn Khôi revolt of 1833. Furthermore, the Catholic Church's strongly anti-communist stance has made it an enemy of the Vietnamese state. The Vatican Church is officially banned, and only government-controlled Catholic organisations are permitted. However, the Vatican has attempted to negotiate the opening of diplomatic relations with Vietnam in recent years.[138]

Several other minority faiths exist in Vietnam. A significant number of people are adherents of Caodaism, an indigenous folk religion which has structured itself on the model of the Catholic Church. Sunni and Cham Bani Islam is primarily practiced by the ethnic Cham minority, though there are also a few ethnic Vietnamese adherents in the southwest. In total, there are approximately 70,000 Muslims in Vietnam,[139] while around 50,000 Hindus and a small number of Baha'is are also in evidence.

The Vietnamese government rejects allegations that it does not allow religious freedom. The state's official position on religion is that all citizens are free to their belief, and that all religions are equal before the law.[140] Nevertheless, only government-approved religious organisations are allowed; for example, the South Vietnam-founded Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam is banned in favour of a communist-approved body.[141]

Education

Vietnam has an extensive state-controlled network of schools, colleges and universities, and a growing number of privately run and partially privatised institutions. General education in Vietnam is divided into five categories: kindergarten, elementary schools, middle schools, high schools, and universities. A large number of public schools have been constructed across the country to raise the national literacy rate, which stood at 90.3% in 2008.[142]

A large number of Vietnam's most acclaimed universities are based in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City. Facing serious crises, Vietnam's education system is under a holistic program of reform launched by the government. Education is not free; therefore, some poor families may have trouble paying tuition for their children without some form of public or private assistance. Regardless, school enrollment is among the highest in the world,[143][144] and the number of colleges and universities increased dramatically in the 2000s, from 178 in 2000 to 299 in 2005.

Health

In 2009, Vietnam's national life expectancy stood at 76 years for women and 72 for men,[145] and the infant mortality rate was 12 per 1,000 live births.[146] By 2009, 85% of the population had access to improved water sources.[145] However, malnutrition is still common in the rural provinces.[147] In 2001, government spending on health care corresponded to just 0.9% of Vietnam's gross domestic product (GDP), with state subsidies covering only about 20% of health care expenses.[148]

In 1954, North Vietnam established a public health system that reached down to the hamlet level.[149] After the national reunification in 1975, a nationwide health service was established. In the late 1980s, the quality of healthcare declined to some degree as a result of budgetary constraints, a shift of responsibility to the provinces, and the introduction of charges. Inadequate funding has also contributed to a shortage of nurses, midwives, and hospital beds; in 2000, Vietnam had only 250,000 hospital beds, or 14.8 beds per 10,000 people, according to the World Bank.[148]

Since the early 2000s, Vietnam has made significant progress in combating malaria, with the malaria mortality rate falling to about 5% of its 1990s equivalent by 2005, after the country introduced improved antimalarial drugs and treatment. However, tuberculosis cases are on the rise, with 57 deaths per day reported in May 2004. With an intensified vaccination program, better hygiene, and foreign assistance, Vietnam hopes to reduce sharply the number of TB cases and annual new TB infections.[148]

As of September 2005, Vietnam had diagnosed 101,291 HIV cases, of which 16,528 progressed to AIDS, and 9,554 died. However, the actual number of HIV-positive individuals is estimated to be much higher. On average, 40–50 new infections are reported every day in Vietnam. As of 2007, 0.5% of the population is estimated to be infected with HIV, and this figure has remained stable since 2005.[150] In June 2004, the United States announced that Vietnam would be one of 15 nations to receive funding as part of a US$15 billion global AIDS relief plan.[148]

Culture

Vietnam's culture has developed over the centuries from indigenous ancient Đông Sơn culture with wet rice agriculture as its economic base. Some elements of the national culture have Chinese origins, drawing on elements of Confucianism and Taoism in its traditional political system and philosophy. Vietnamese society is structured around làng (ancestral villages); all Vietnamese mark a common ancestral anniversary on the tenth day of the third lunar month.[151] The influences of immigrant peoples – such as the Cantonese, Hakka, Hokkien and Hainan cultures – can also be seen, while the national religion of Buddhism is strongly entwined with popular culture. In recent centuries, the influences of Western cultures, most notably France and the United States, have become evident in Vietnam.

The traditional focuses of Vietnamese culture are humanity (nhân nghĩa) and harmony (hòa); family and community values are highly regarded. Vietnam reveres a number of key cultural symbols, such as the Vietnamese dragon, which is derived from crocodile and snake imagery; Vietnam's National Father, Lạc Long Quân, is depicted as a holy dragon. The lạc – a holy bird representing Vietnam's National Mother, Âu Cơ – is another prominent symbol, while turtle and horse images are also revered.[152]

In the modern era, the cultural life of Vietnam has been deeply influenced by government-controlled media and cultural programs. For many decades, foreign cultural influences – especially those of Western origin – were shunned. However, since the 1990s, Vietnam has seen a greater exposure to Southeast Asian, European and American culture and media.[153]

Media

Vietnam's media sector is regulated by the government in accordance with the 2004 Law on Publication.[154] It is generally perceived that Vietnam's media sector is controlled by the government to follow the official Communist Party line, though some newspapers are relatively outspoken.[155] The Voice of Vietnam is the official state-run national radio broadcasting service, broadcasting internationally via shortwave using rented transmitters in other countries, and providing broadcasts from its website. Vietnam Television is the national television broadcasting company.

Since 1997, Vietnam has extensively regulated public Internet access, using both legal and technical means. The resulting lockdown is widely referred to as the "Bamboo Firewall".[156] The collaborative project OpenNet Initiative classifies Vietnam's level of online political censorship to be "pervasive",[157] while Reporters Without Borders considers Vietnam to be one of 15 global "internet enemies".[158] Though the government of Vietnam claims to safeguard the country against obscene or sexually explicit content through its blocking efforts, many politically and religiously sensitive websites are also banned.[159]

Music

Traditional Vietnamese music varies between the country's northern and southern regions. Northern classical music is Vietnam's oldest musical form, and is traditionally more formal. The origins of Vietnamese classical music can be traced to the Mongol invasions of the 13th century, when the Vietnamese captured a Chinese opera troupe.[160] Throughout its history, Vietnamese has been most heavily impacted by the Chinese musical tradition, as an integral part, along with Korea, Mongolia and Japan.[161] Nhã nhạc is the most popular form of imperial court music. Chèo is a form of generally satirical musical theatre. Xẩm or Hát xẩm (Xẩm singing) is a type of Vietnamese folk music. Quan họ (alternate singing) is popular in Hà Bắc (divided into Bắc Ninh and Bắc Giang Provinces) and across Vietnam. Hát chầu văn or hát văn is a spiritual form of music used to invoke spirits during ceremonies. Nhạc dân tộc cải biên is a modern form of Vietnamese folk music which arose in the 1950s. Ca trù (also hát ả đào) is a popular folk music. "Hò" can not be thought of as the southern style of Quan họ. There are a range of traditional instruments, including the Đàn bầu (a monochord zither), the Đàn gáo (a two-stringed fiddle with coconut body), and the Đàn nguyệt (a two-stringed fretted moon lute).

Literature

Vietnamese literature has a centuries-deep history. The country has a rich tradition of folk literature, based on the typical 6–to-8-verse poetic form named ca dao, which usually focuses on village ancestors and heroes.[162] Written literature has been found dating back to the 10th-century Ngô dynasty, with notable ancient authors including Nguyễn Trãi, Trần Hưng Đạo, Nguyễn Du and Nguyễn Đình Chiểu. Some literary genres play an important role in theatrical performance, such as hát nói in ca trù.[163] Some poetic unions have also been formed in Vietnam, such as the Tao Đàn. Vietnamese literature has in recent times been influenced by Western styles, with the first literary transformation movement – Thơ Mới – emerging in 1932.[164]

Festivals

Vietnam has a plethora of festivals based on the lunar calendar, the most important being the Tết New Year celebration. Traditional Vietnamese weddings remain widely popular, and are often celebrated by expatriate Vietnamese in Western countries.

Tourism

Vietnam has become a major tourist destination since the 1990s, assisted by significant state and private investment, particularly in coastal regions.[165] About 3.77 million international tourists visited Vietnam in 2009 alone.[166]

Popular tourist destinations include the former imperial capital of Hué, the World Heritage Sites of Phong Nha-Kẻ Bàng National Park, Hội An and Mỹ Sơn, coastal regions such as Nha Trang, the caves of Hạ Long Bay and the Marble Mountains. Numerous tourist projects are under construction, such as the Bình Dương tourist complex, which possesses the largest artificial sea in Southeast Asia.[167]

On 14 February 2011, Joe Jackson, the father of American pop star Michael Jackson, attended a ground breaking ceremony for what will be Southeast Asia's largest entertainment complex, a five-star hotel and amusement park called Happyland. The US$2 billion project, which has been designed to accommodate 14 million tourists annually, is located in southern Long An Province, near Ho Chi Minh City. It is expected that the complex will be completed in 2014.[168]

Clothing

The áo dài, a formal dress, is worn for special occasions such as weddings and religious festivals. White áo dài is the required uniform for girls in many high schools across Vietnam. Áo dài was once worn by both genders, but today it is mostly the preserve of women, although men do wear it to some occasions, such as traditional weddings.[169] Other examples of traditional Vietnamese clothing include the áo tứ thân, a four-piece woman's dress; the áo ngũ, a form of the thân in 5-piece form, mostly worn in the north of the country; the yếm, a woman's undergarment; the áo bà ba, rural working "pyjamas" for men and women;[170] the áo gấm, a formal brocade tunic for government receptions; and the áo the, a variant of the áo gấm worn by grooms at weddings. Traditional headwear includes the standard conical nón lá and the "lampshade-like" nón quai thao.

Sport

The Vovinam and Bình Định martial arts are widespread in Vietnam,[171] while soccer is the country's most popular team sport.[172] Its national team won the ASEAN Football Championship in 2008. Other Western sports, such as badminton, tennis, volleyball, ping-pong and chess, are also widely popular.

Vietnam has participated in the Summer Olympic Games since 1952, when it competed as the State of Vietnam. After the partition of the country in 1954, only South Vietnam competed in the Games, sending athletes to the 1956 and 1972 Olympics. Since the reunification of Vietnam in 1976, it has competed as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, attending every Summer Olympics from 1988 onwards. The present Vietnam Olympic Committee was formed in 1976 and recognized by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in 1979.[173] As of 2014, Vietnam has never participated in the Winter Olympics. In 2016, Vietnam participated in the Rio Olympics, where they won their first gold medal.[174]

Cuisine

Vietnamese cuisine traditionally features a combination of five fundamental taste "elements" (Vietnamese: ngũ vị): spicy (metal), sour (wood), bitter (fire), salty (water) and sweet (earth).[175] Common ingredients include fish sauce, shrimp paste, soy sauce, rice, fresh herbs, fruits and vegetables. Vietnamese recipes use lemongrass, ginger, mint, Vietnamese mint, long coriander, Saigon cinnamon, bird's eye chili, lime and basil leaves.[176] Traditional Vietnamese cooking is known for its fresh ingredients, minimal use of oil, and reliance on herbs and vegetables, and is considered one of the healthiest cuisines worldwide.[177]

In northern Vietnam, local foods are often less spicy than southern dishes, as the colder northern climate limits the production and availability of spices. Black pepper is used in place of chilis to produce spicy flavors. The use of such meats as pork, beef, and chicken was relatively limited in the past, and as a result freshwater fish, crustaceans – particularly crabs – and mollusks became widely used. Fish sauce, soy sauce, prawn sauce, and limes are among the main flavoring ingredients. Many signature Vietnamese dishes, such as bún riêu and bánh cuốn, originated in the north and were carried to central and southern Vietnam by migrants.[178]

See also

- Corruption in Vietnam

- Effects of Agent Orange on the Vietnamese people

- Index of Vietnam-related articles

- Outline of Vietnam

- Vietnam Coast Guard

- Vietnam People's Public Security

- Women in Vietnam

Notes

- ↑ Only the first verse of the "Army March" is recognized as the official national anthem of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

- ↑ Also called Kinh people[1]

- ↑ In effect since 1 January 2014

- ↑ The South China Sea is referred to in Vietnam as the East Sea (Biển Đông).[7]

- ↑ At first, Gia Long requested the name Nam Việt, but the Jiaqing Emperor refused.[10]

- ↑ Neither the United States government nor Ngô Đình Diệm's State of Vietnam signed anything at the 1954 Geneva Conference. The non-communist Vietnamese delegation objected strenuously to any division of Vietnam; however, the French accepted the Viet Minh proposal[38] that Vietnam be united by elections under the supervision of "local commissions".[39] The United States, with the support of South Vietnam and the United Kingdom, countered with the "American Plan,"[40] which provided for United Nations-supervised unification elections. The plan, however, was rejected by Soviet and other communist delegations.[40]

References

- Citations

- ↑ "Dân tộc Kinh" (in Vietnamese). Communist Party of Vietnam. 15 October 2004. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- 1 2 Robbers, Gerhard (30 January 2007). Encyclopedia of world constitutions. Infobase Publishing. p. 1021. ISBN 978-0-8160-6078-8. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Vietnam – Geography". Index Mundi. 12 July 2011. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "World Economic Outlook: Vietnam". International Monetary Fund. October 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- 1 2 "2015 Human Development Report Summary" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2015. pp. 13, 17. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ↑ Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], Peter Roach, James Hartmann and Jane Setter, eds., English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 3-12-539683-2

- ↑ "China continues its plot in the East Sea". Vietnamnet News. 10 December 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- 1 2 "Vietnam's new-look economy". BBC News. 18 October 2004. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ↑ Weisenthal, Joe (22 February 2011). "3G Countries". Business Insider. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- 1 2 Woods 2002, p. 38

- ↑ Yue-Hashimoto 1972, p. 1

- ↑ Thành Lân (14 March 2003). "Ai đặt quốc hiệu Việt Nam đầu tiên?" (in Vietnamese). Vietnam Embassy in the United States. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ↑ 《嘉庆重修一统志》卷五五三

- ↑ Tonnesson & Antlov 1996, p. 117

- ↑ Tonnesson & Antlov 1996, p. 126

- ↑ "The Human Migration: Homo erectus and the Ice Age". Yahoo!. 27 May 2009. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ↑ Kha and Bao, 1967; Kha, 1975; Kha, 1976; Long et al., 1977; Cuong, 1985; Ciochon and Olsen, 1986; Olsen and Ciochon, 1990.

- 1 2 Cuong, 1986.

- ↑ Colani, 1927.

- ↑ Demeter, 2000.

- ↑ "Dong Son culture". LittleVietnamTours.com.vn. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ Nola Cooke, Tana Li, James Anderson (2011). The Tongking Gulf Through History. p.46: "Nishimura actually suggested the Đông Sơn phase belonged in the late metal age, and some other Japanese scholars argued that, contrary to the conventional belief that the Han invasion ended Đông Sơn culture, Đông Sơn artifacts, ..."

- ↑ Vietnam Fine Arts Museum (2000). "... the bronze cylindrical jars, drums, Weapons and tools which were sophistically carved and belonged to the World famous Đông Sơn culture dating from thousands of years; the Sculptures in the round, the ornamental architectural Sculptures ..."

- ↑ "Chinese Colonization (200BC – 938AD)". Asia.msu.edu. Archived from the original on 25 August 2007. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ "Country's Official Name". Easy Riders Vietnam. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ "Spears offer insight into early military strategy". Viet Nam News. 22 January 2006. Archived from the original on 4 March 2009.

- ↑ "The Trần Dynasty and the Defeat of the Mongols". Countrystudies.us. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ "The Lê Dynasty and Southward Expansion". Countrystudies.us. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ "The Kingdom of Champa". Ancientworlds.net. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ "The Chams: Survivors of a Lost Civilisation". Cpamedia.com. Archived from the original on 10 January 2010. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ Colonialism by Melvin Eugene Page and Penny M. Sonnenburg via Google Books. p.723. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ↑ "French Counterrevolutionary Struggles: Indochina and Algeria" (PDF). United States Military Academy. 1968. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ↑ Fourniau, Annam–Tonkin, pp. 39–77

- ↑ "1930: 13 Viet Nam Quoc Dan Dang cadres, for the Yen Bai mutiny". ExecutedToday.com. 17 June 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- 1 2 Hirschman, Charles; Preston, Samuel; Vu Manh Loi (1995). "Vietnamese Casualties During the American War: A New Estimate" (PDF). Population and Development Review. 21 (4): 783–812. doi:10.2307/2137774. JSTOR 2137774. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2010.

- ↑ "Vietnam Notebook: First Indochina War, Early Years (1946–1950)". Parallel Narratives. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ↑ Declaration of Independence, Democratic Republic of Vietnam (2 September 1945). Vietnam Documents. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ↑ The Pentagon Papers (1971). Beacon Press. Vol. 3. p. 134.

- ↑ The Pentagon Papers (1971). Beacon Press. Vol. 3. p. 119.

- 1 2 The Pentagon Papers (1971). Beacon Press. Vol. 3. p. 140.

- ↑ "Vietnam's 300 Days of Open Borders: Operation Passage to Freedom". Library of Economics and Liberty. 3 July 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ↑ Moïse, Edwin (4 November 1998). "The Geneva Accords". Clemson University. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ↑ Moïse, Edwin (4 November 1998). "The Aftermath of Geneva, 1954–1961". Clemson University. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ↑ The United States in Vietnam – An Analysis in Depth of America's Involvement in Vietnam. George McTurnin Kahin and John W. Lewis (1967). Delta Books.

- ↑ Turner, Robert F. (1975). Vietnamese Communism: Its Origins and Development. Hoover Institution Publications. p. 143. ISBN 978-0817964313.

- ↑ cf. Gittinger, J. Price, "Communist Land Policy in Viet Nam", Far Eastern Survey, Vol. 29, No. 8, 1957, p. 118.

- ↑ Courtois, Stephane; et al. (1997). The Black Book of Communism. Harvard University Press. p. 569. ISBN 978-0-674-07608-2.

- ↑ Dommen, Arthur J. (2001), The Indochinese Experience of the French and the Americans, Indiana University Press, p. 340, gives a lower estimate of 32,000 executions.

- ↑ "Newly released documents on the land reform". Vietnam Studies Group. Retrieved 2016-07-15.

Vu Tuong: There is no reason to expect, and no evidence that I have seen to demonstrate, that the actual executions were less than planned; in fact the executions perhaps exceeded the plan if we consider two following factors. First, this decree was issued in 1953 for the rent and interest reduction campaign that preceded the far more radical land redistribution and party rectification campaigns (or waves) that followed during 1954-1956. Second, the decree was meant to apply to free areas (under the control of the Viet Minh government), not to the areas under French control that would be liberated in 1954-1955 and that would experience a far more violent struggle. Thus the number of 13,500 executed people seems to be a low-end estimate of the real number. This is corroborated by Edwin Moise in his recent paper "Land Reform in North Vietnam, 1953-1956" presented at the 18th Annual Conference on SE Asian Studies, Center for SE Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley (February 2001). In this paper Moise (7-9) modified his earlier estimate in his 1983 book (which was 5,000) and accepted an estimate close to 15,000 executions. Moise made the case based on Hungarian reports provided by Balazs, but the document I cited above offers more direct evidence for his revised estimate. This document also suggests that the total number should be adjusted up some more, taking into consideration the later radical phase of the campaign, the unauthorized killings at the local level, and the suicides following arrest and torture (the central government bore less direct responsibility for these cases, however).

cf. Szalontai, Balazs (November 2005). "Political and Economic Crisis in North Vietnam, 1955–56". Cold War History. 5 (4): 395–426. cf. Vu, Tuong (2010). Paths to Development in Asia: South Korea, Vietnam, China, and Indonesia. Cambridge University Press. p. 103. ISBN 9781139489010. - ↑ Turner, Robert F. (1975). Vietnamese Communism: Its Origins and Development. Hoover Institution Publications. pp. 174–178. ISBN 978-0817964313.

- ↑ Spencer C. Tucker, ed. (2011). The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO via Google Books. ISBN 9781851099610. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ↑ "JFK and the Diem Coup". National Security Archive. 5 November 2003. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ↑ "This Day in History (Sep 3, 1967): Thieu-Ky ticket wins national election". History.com. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- ↑ "Vietnam War". Seasite.niu.edu. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ "The War's Costs". DigitalHistory.uh.edu. 2006. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ↑ "Soviet Aid to North Vietnam". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ↑ "Chinese Support for North Vietnam during the Vietnam War: The Decisive Edge". Military History Online. 2008. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ↑ "Riding Vietnam's Ho Chi Minh Trail". The Guardian. 28 July 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ↑ "Tet Offensive". Vets With A Mission. Retrieved 10 October 2012. "...NLF/NVA troops and commandos attacked virtually every major town and city in South Vietnam as well as most of the important American bases and airfields...In Saigon, nineteen VC commandos blew their way through the outer walls of the US Embassy..."

- ↑ "The Massacre at Hue". TIME. 31 October 1969. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ↑ Turner, Robert F. (1975). Vietnamese Communism: Its Origins and Development. Hoover Institution Publications. p. 251. ISBN 978-0817964313.

- ↑ "Vietnamization". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ↑ "Saigon's Finale". New York Times. 13 October 1999. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ↑ Shenon, Philip (23 April 1995). "20 Years After Victory, Vietnamese Communists Ponder How to Celebrate". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ↑ Associated Press (3 April 1995). "Vietnam Says 1.1 Million Died Fighting For North."

- ↑ Elliot, Duong Van Mai (2010). "The End of the War". RAND in Southeast Asia: A History of the Vietnam War Era. RAND Corporation. pp. 499, 512–513. ISBN 9780833047540.

- ↑ Sagan, Ginetta; Denney, Stephen (October–November 1982). "Re-education in Unliberated Vietnam: Loneliness, Suffering and Death". The Indochina Newsletter. Retrieved 2016-09-01.

- ↑ "Vietnam Outlines Collectivization Goal". The Spokesman-Review. Google News Archive. 28 June 1977. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ Cambodia – The Fall of Democratic Kampuchea. U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ↑ "Photographer Showcases Legendary Khmer Temple Preah Vihear". National Geographic. 23 June 2009. Archived from the original on 4 August 2009. Retrieved 12 July 2010.

- ↑ Chinese Invasion of Vietnam – February 1979. GlobalSecurity.org. Updated 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- 1 2 Stowe, Judy (28 April 1998). "Obituary: Nguyen Van Linh". The Independent (London). p. 20.

- 1 2 Ackland, Len (20 March 1988). "Long after U.S. war, Vietnam is still a mess". St. Petersburg Times (Florida). Page 2-D.

- ↑ Murray, Geoffrey (1997). Vietnam: Dawn of a New Market. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 24–25. ISBN 0-312-17392-X.

- 1 2 Hoang Thi Bich Loan (18 April 2007). "Consistently pursuing the socialist orientation in developing the market economy in Vietnam". Communist Review. TạpchíCộngsản.org.vn. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011.

- ↑ Palace of Supreme Harmony in Hue (Vietnam) Wagstaff, A.; Van Doorslaer, E.; Watanabe, N. (2003). "On decomposing the causes of health sector inequalities with an application to malnutrition inequalities in Vietnam". Journal of Econometrics. 112: 207. doi:10.1016/S0304-4076(02)00161-6.

- ↑ Goodkind, D. (1995). "Rising Gender Inequality in Vietnam Since Reunification". Pacific Affairs. 68 (3): 342–359. doi:10.2307/2761129. JSTOR 2761129.

- ↑ Gallup, John Luke (2002). "The wage labor market and inequality in Viet Nam in the 1990s". Ideas.repec.org. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- ↑ Johnson, Kay (22 February 2007). "The Spoils of Capitalism". Time. New York. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- ↑ "A bit of everything: Vietnam's quest for role models". The Economist. London. 24 April 2008. Retrieved 19 May 2010. (subscription required)

- ↑ "UN urged to act on Vietnam over death penalty". The Washington Post. 12 February 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ↑ International Institute for Strategic Studies; Hackett, James (ed.) (3 February 2010). The Military Balance 2010. London: Routledge. ISBN 1-85743-557-5.

- ↑ The SIPRI Military Expenditure Database. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ↑ "Escalating Tensions in the South China Sea". The National Interest. 10 September 2012.

- 1 2 "Vietnam Foreign Policy". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ↑ "List of countries which maintain diplomatic relations with the Socialist Republic of Vietnam". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. December 2007. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ↑ "US-Vietnamese Relations". US Embassy. Retrieved 8 December 2009.

- ↑ "Vietnam and International Organizations". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ↑ Matt Spetalnick (March 23, 2016). "U.S. Lifts arms ban on old foe Vietnam as regional tensions simmer". Reuters. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ↑ "Agricultural advanced technologies in Red river delta, Viet Nam these days". Agroviet Newsletter. September 2005. Archived from the original on 21 February 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Báo cáo Hiện trạng môi trường quốc gia 2005" (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on 23 February 2009.

- ↑ "Edwards's Pheasant (Lophura edwardsi)". BirdLife International. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- ↑ Kinver, Mark (25 October 2011). "Javan rhino 'now extinct in Vietnam'". BBC News. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ↑ "The Vietnamese Stock Market" (PDF). Financial Women's Association of New York. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ↑ "Vietnam may be fastest growing emerging economy" (Press release). PricewaterhouseCoopers. 12 March 2008. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ↑ "Vietnam to be listed among top economies by 2050: HSBC". Tuổi Trẻ News. 14 January 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012. Archived 16 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine.