Vought Airtrans

|

Vought Airtrans passenger vehicle in operation at DFW International Airport | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Locale | Dallas/Fort Worth Airport, Texas |

| Transit type | People mover |

| Number of stations | 33 |

| Daily ridership | 250 million over lifetime |

| Operation | |

| Began operation | January, 1974 |

| Operator(s) | Dallas/Fort Worth Airport |

| Number of vehicles | 68 |

| Train length | 21 feet per vehicle |

| Headway | 165 feet |

| Technical | |

| System length | 15 mi (24.14 km) |

| Top speed | 17mph |

LTV's (Vought) Airtrans was an automated people mover system that operated at Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport between 1974 and 2005. The adaptable people mover was utilized for several separate systems: the Airport Train, Employee Train, American Airlines TrAAin and utility service. All systems utilized the same guideways and vehicle base but served different stations to create various routes.

After 30 years of service the system's 1970s technology was no longer adequate for the expanding airport's needs, and in 2005 it was replaced by the current Skylink system. While most of the system was auctioned and sold for scrap, some guideways and stations (some of which are still open to the public) remain. Airtrans moved nearly 5 million people in its first year of operation; by the end of its life it had served over 250 million passengers.[1][2]

As the first US installation of a fully automated transit system, Airtrans technology was expected to be deployed in similar mass transit systems around the country. In Japan, the system was licensed by a consortium formed between Niigata Engineering and Sumitomo Corporation for similar deployments there.[3] However, no further systems were constructed. Car #25 was donated to the Frontiers of Flight Museum in Dallas, Texas, and Cars #30 and #82 were donated to North Texas Historic Transportation in Fort Worth, Texas.[4][5]

History

Background

During the early 1960s there was growing concern in the United States about the effects of urban sprawl and the resulting urban decay that followed. Major cities across the country were watching their downtown cores turn into ghost towns as the suburbs expanded and caused a flight of capital out of the cities. The only cities that were combatting this were the ones with effective mass transit systems, cities like New York City and Boston, where the utility of the subway was greater than a car. However, these solutions were extremely expensive to develop, well beyond the budgets of smaller cities or the suburbs of larger ones. Through the 1960s there was a growing movement in urban planning circles that the solution was the personal rapid transit system, small automated vehicles that were much less expensive to develop.

At the same time, as Project Apollo wound down and President Richard Nixon started disengaging from the Vietnam War, there was considerable concern in the aerospace industry that the 1970s and 1980s would be lean times. The highly automated operation the PRT systems required, along with the project management needed to build a large mass transit system, was a natural fit for the aerospace companies to provide and by the late 1970s many were working on PRT systems. In 1970 LTV joined these efforts, when the Vice President of Engineering formed a study team to investigate ground transportation systems. They sketched out a system using off-the-shelf hardware to build a new PRT design.[6]

DFW bid

The Dallas/Fort Worth Airport had recently started construction, and a people mover was one of their requirements. The airport consisted of four semi-circular terminal areas arranged in a line with large parking lots on either ends of the line, and two hotel towers in the middle. It was miles from one end to the other, so some form of rapid transit was needed to move people around the complex. DFW wanted the system to transport not only people, but mail, trash, supplies, and baggage as well. Varo Corp. had recently purchased the Monocab concept from its private developer and were pitching the system to DFW. LTV was asked to join them in a joint proposal, which was submitted late in 1970, along with two others from different providers. However, all three were over the price the airport had budgeted, and the companies were asked to re-submit.[6]

Varo declined, and sold their interest in Monocab to Rohr, Inc., which later re-emerged as the Rohr ROMAG. LTV decided to submit their original design for the May 1971 deadline, developing their guideway to match existing highway specifications and construction techniques as a way to lower costs. Since they had no time to develop prototype hardware, they instead backed up their proposal with an extensive computer simulation of full operations. Westinghouse and Dashaveyor (Bendix) also entered designs, but LTV's simulation proved decisive and they were announced as the winner on 2 August 1971.[7] The contract stipulated that the system had to be operational on 13 July 1973.[7]

Construction of the Airtrans guideway took place almost on-schedule, which turned out to be better than the airport itself. When DFW opened in January 1974, Airtrans, which had been heralded as "people mover of the future,' quickly fell short of expectations. Originally operating between 7 a.m. and 10 p.m., it worked reliably only 56 percent of the time. A more serious problem was the budget. Originally bid at $34 million, a series of problems led Vought to declare a $22.6 million loss on the project.[8]

Service life

.jpg)

In accordance with the original contract specifications, Airtrans was originally built to support both freight and passenger service. Inter-terminal baggage was handled by 89 LD3 containers, which were loaded on a series of semi-automated conveyor belt systems at each terminal. During construction the airport demanded a lower required time for inter-terminal handling, and a different system had to be installed that could meet these increased speeds - the Airtrans baggage handling system was never used in operations. Likewise, the mail handling services were demonstrated at the "Air Mail Facility", but the USPS declined to use it as they felt it was too demanding in that it required their employees to interface with an automatic system.[9] An incinerator was built for trash handling, but never worked properly and was never put into use. Instead, trash from the terminals was moved on the existing passenger vehicles after hours. In the end, only the supplies facility would use the cargo vehicles, operating with great success until 1991 when increased demands for passenger services forced the cargo vehicles to be converted to passenger bodies.[9][10]

In service, the Airtrans system had a number of unexpected problems. The system was originally designed for typical Dallas weather, which rarely sees snow, and it was expected that the normal operations would keep the guideway clear when snow did fall. In operation, snow and ice proved to be a serious problem, but a detailed study on ways to keep the system clear demonstrated it would be less expensive to provide truck services during those rare periods.[11][12] Additionally, maintaining the vehicles proved more difficult than expected, but DFW's transportation department kept updating the system, one piece at a time. Wiring and electronic components were moved inside the Airtrans cars; they had been exposed to weather under the cars. Circuit boards were replaced with microchips. After fifteen years of continual improvement, the system emerged as a paragon of reliability. At its peak in 1987, the system carried 23,000 passengers a day. In 1988, now operating 24 hours, the system achieved a 99.8% in-service record.[10] In 1989 the vehicles were refurbished to improve maintenance and cleaning operations.[13] When Airtrans made its debut, it used eight-track cartridges for its announcements; the audio system was later upgraded to a cassette system, and still later to a digital voice synthesizer.

The system was originally installed in an era of very different security concerns, and operated on both sides of the modern secure/insecure line. The insecure side was used by passengers moving between the terminals and to and from the parking lots, the secure side for employees moving around the airport and for cargo services (when they were used). This forced employees to transit through security when moving to and from the line when new security arrangements were added. A solution to this problem was easily implemented by moving the employee side doors to the opposite side of the platform, then sending in some of the cars "backwards" so the doors were on the other side. With this change the new routes became the "Employee Train", while the passenger side became the "Airport Train".[10] Another modification was added between 1990 and 1991 to service American Airlines passengers moving between terminals 3E and 2E (today known as Terminals A & C), known as the “TrAAin" or "AAirtrans Express". An additional crossover connecting east and west sides of the airport was added to the system in 1997 and 1998.

As the original lifetime of the vehicles approached, DFW started studying replacing the system. As LTV had long exited the transit business, and no other companies offered similar AGT systems that could be adapted to the existing network, an entirely new system was needed and eventually won by the Bombardier Innovia APM 200. Since the system required entirely new guideways, the Airtrans system would have to be kept operational while the new system was installed. A mid-life upgrade process, mostly guideway improvements, was implemented in 1998.[14] Passenger operations started to wind down in 2003, replaced by a shuttle bus service. Employee Train operations ended on 9 May 2005, followed by TrAAin on 20 May. The new Skylink service opened the next day.[10]

Other developments

In 1976 Vought was awarded a $7 million contract by the Urban Mass Transit Administration to study modifications needed to produce a version of Airtrans suitable for mass transit applications. Changes were aimed primarily at increasing the speed from 17 to 30 mph, along with changes to reduce capital costs of implementing systems. Vought used one of the production cargo vehicles as an instrumented testbed, running it on the existing DFW guideways at increased speeds, and used the information collected to determine what changes would need to be made to provide this performance in an operational setting. Several changes were needed; the power collection arms that pressed against the wires on the track side had to be modified to a design originally considered for the DFW system, the steering had to be upgraded in order to switch quickly enough, and to improve energy use, the new vehicles also featured regenerative braking. A non-mechanical steering system reading a ferrous stripe in the center of the guideway was also tried, but abandoned as not necessary for speeds up to 30 mph.[15]

Nothing ever came of these proposals, and LTV exited the AGT market.

System operations

Vehicles

The Airtrans vehicles were 21 feet (6.4 m) long, 7 feet (2.1 m) wide, and 10 feet (3.0 m) high and had an empty weight of 14,000 lbs. The chassis was based on a large electrically powered bus, built of steel and running on foam-filled tires with air-bag suspensions. A linkage between the front and rear wheels provided four-wheel steering.[16]

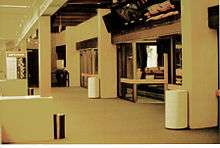

Passenger vehicles contained longitudinal seating for up to 16 passengers and standing room for up to 24 people (for a total of 40). The bodywork was made of acrylic-coated fiberglass and an automatic door was located on only one side. Across from the door a raised area provided room for hand luggage while hiding the manual controls.[10] Emergency exits were located on each end of the vehicle.[16] The passenger vehicles could be coupled to form 2- (or later) 3-car trains. The bi-directional motor could be switched and the car repositioned on the guideway to provide a right-opening or left-opening door.[16]

For cargo vehicles, the passenger bodywork was replaced with a flatbed containing three powered conveyor belts for loading cargo, sized to handle three LD3 containers.

Vehicles operated with five blocks (consisting of 90 feet (27 m) each) of guideway between vehicles. Full speed was allowed in the first, reduced speeds in the next two, and full stop in the last two. The vehicles required 165 feet (50 m) to stop completely. These large headways reduced passenger capacity and required multiple vehicles to make up for this.

Operations were normally handled by two operators in the control center.[9] Vehicles were equipped with two-way communications to allow passengers to talk to the operators in an emergency.[16]

The vehicles were original painted brown on the exterior with orange and yellow interiors, matching the color scheme of the airport. In 1989 the cars were refurbished, resulting in a blue and white theme and more durable interiors.[17]

Guideways and power supply

Guideways were made of concrete and based on highway construction techniques. The varying topography of the airport resulted in both aerial and ground level guideways winding their way over and under public roadways. As the guideway entered the semicircular terminals or remote parking areas, it remained at ground/ramp level and under the terminal building. At these terminal areas the guideway branched out to serve various stations, bypass tracks and vehicle storage sidings. Additional bypass guideways were constructed as the airport expanded. At several locations along the guideway tug sidings were located near the airport service road, allowing a disabled vehicle to be removed from the guideway and towed to the maintenance facility.

The guideway was uni-directional, with all vehicles traveling around the airport in a counter-clockwise direction. The top of guideway walls contained rails that steered the vehicles. Small urethane wheels on either side of the vehicle engaged the rail and were mechanically linked to a conventional steering suspension on the main wheels. Switching was provided by switching bars on either side of the guideway that raised or lowered to trap one of the two sets of guidance wheels under them. The switch was adapted from existing fail-safe switches used on railways.

Power was supplied in three-phase form at 480 VAC through three conductor strips on the guideway wall.[18] Below the conductors was a common ground, and above it was an inductive loop used for signalling. Mechanical "feelers" extending from the corners of the vehicle with brushes on their ends engaged the conductors. Power was rectified and fed into a DC motor, which was attached to a conventional differential and then to the wheels at one end. The motor was bi-directional and was switched depending on the vehicle's direction of travel.[16]

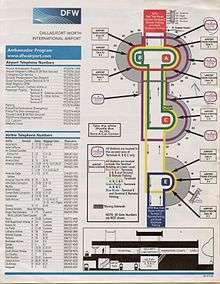

Routes and stations

Airtrans was operated over a number of fixed routes throughout the airport. Each route could be modified using different stations, guideways and vehicle configurations. Conversion of the system to offer point-to-point service like a true group rapid transit system was considered but not implemented, although all stations contained bypass tracks or vehicles could proceed through lower-demand stations without stopping. The flexibility of the system resulted in routes that changed often to serve different airline and passenger needs. While initially planned for "origin and destination" traffic, the system was modified to move connecting passengers (although never very effectively due to its uni-directional operation). The initial service specifications allowed for a maximum inter-terminal trip of 20 minutes, and 30 minutes to remote parking.[19]

Airtrans was built to serve 53 passenger, employee and service stations around the airport, 33 of those for passengers and employees.[20] Each terminal contained 3 passenger stations corresponding to that terminal's section (for example, Terminal 2E Section 1) located adjacent to the lower level terminal drive. These passenger stations contained an enclosed waiting area, destination signage, two sets of bi-parting automatic doors (with room for a third) and elevators to upper level ticketing/baggage claim. In early years of operation entry to the station was gained by placing a quarter in and passing through entry turnstiles. An employee station for each terminal section was located on a separate guideway adjacent to the terminal's ramp area, and screened from passenger view. These stations were more primitive, containing an outdoor waiting area with a fence and no automatic doors preventing access to the electrified guideway.[19]

The North (1W) and South (5E) Remote Parking areas each contained two stations; an additional station served the airport hotel. These stations consisted of two platforms on either side of a single guideway: an enclosed passenger station and an exposed employee station. Transfer to either side of the guideway was accommodated by a sheltered elevated or below-station walkway.

At the time of opening Airtrans routes consisted of 5 passenger routes (3 inter-terminal, 2 remote parking) and 4 employee routes (directly connecting 1 terminal to 1 remote parking station). On-demand cargo service served various cargo stations located at the terminals. Two air mail routes were put in service for the U.S. Postal Service, but they were soon terminated when demand outpaced capacity and equipment did not interface well.[21]

In 1991 American Airlines built 2 new stations each in Terminals A (2E) and C (3E) for $38 million as part of the new "TrAAm" (later, "TrAAin" service).[22] The modern stations, built adjacent to employee stations on the secure ramp side, allowed connecting passengers to transfer between American's terminals without exiting security to use the inter-terminal airport train. These stations provided escalator service directly to the terminal gate areas. A fifth TrAAin station serving Terminal B (2W) was later constructed along a guideway when American Airlines expanded to that terminal. This new service resulted in termination of the Airtrans cargo service, as all cargo vehicles were converted to passenger vehicles.

In the final year of operation (2005), Airtrans consisted of the following routes (in order of travel):

Airport Train Red: North Remote Parking Stations B & A; Terminal B (2W) Stations C, B, A; Terminal C (3E) Station B; Terminal A (2E) Station C & A.

Airport Train Green: Terminal B (2W) Stations C, B, A; Terminal C (3E) Station B; Terminal A (2E) Station C & A.

Airport Train Yellow: Terminal B (2W) Stations C, B, A; Terminal E (4E) Stations C, B, A; Terminal C (3E) Station B; Terminal A (2E) Station C & A.

American Airlines TrAAin: Terminal C (3E) Gates C17-C39, Gates C1-C16; Terminal A (2E) Gates A19-A39, Gates A1-A18; Terminal B (2W) Gates B1-B10.

Airport Employee Train: Two routes connecting all terminals with North Remote or South Remote Parking.

Incidents

In 1977, a single Airtrans passenger train slammed into the back of a two-car employee train, injuring nine people. The vehicle was under manual control to bypass a malfunctioning section of guideway in the South Remote Parking Lot.[23]

Two deaths related to Airtrans occurred in September 1977. A teenager was killed after jumping on top of a vehicle from a restricted retaining wall and falling to the guideway, where he was run over by a two-car train. During the same week, a man from Fort Worth was electrocuted and killed when touching a high voltage wire on the guideway.[24]

In 1986, an Airtrans vehicle struck a jogger who had mistaken the guideway for a running path. The man, visiting from Atlanta, was pushed 238 feet (73 m) by the train before a trip wire snapped and stopped the train. He received cuts and abrasions but was not killed.[25]

Specifications

Airtrans facts from DFW Airport:[10]

- 15: Guideway length in miles for all Airport Train routes

- 33: Total number of Airport Train stations

- 68: Number of passenger vehicles in Airport Train fleet

- 11,450: Continuous days of service provided by Airport Train

- 274,800: Continuous hours of service provided by Airport Train

- 250,000,000: Total passengers carried

- 97,000,000: Total mileage run by all Airport Train cars

- $34,000,000: Original contract cost for the Airport Train & guideway

References

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vought Airtrans. |

- ↑ The demonstration of automated guideway transit for accelerated urban deployment. by LTV Corporation. 1975

- ↑ DFW News

- ↑ AGT 1975, pg. 47

- ↑ "Frontiers of Flight"

- ↑ "Equipment Roster". North Texas Historic Transportation. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- 1 2 Vought, Program Background

- 1 2 Vought, System Requirements and LTV's Proposed Solution

- ↑ "The LTV Corporation"

- 1 2 3 Vought, Controls

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Capps 2005

- ↑ Patton, R J and Raven, R R, "Combatting Ice on Airtrans and other Guideways", TRB Special Report 185, Snow Removal and Ice Control Research, p. 328-336

- ↑ Stevens, R D and Nicarico, T J, "All-Weather Protection for AGT Guideways and Stations", TRB Special Report 185, Snow Removal and Ice Control Research, p. 337-342

- ↑ Dallas Morning News, January 8, 1989

- ↑ John Graddy, "Dallas/Fort Worth Airport Train Critical Needs"

- ↑ Corbin

- 1 2 3 4 5 Vought, Vehicles

- ↑ Joe Simnacher. "AIRTRANS RECOVERS FROM A ROUGH START." The Dallas Morning News 8 Jan. 1989, HOME FINAL, SPECIAL: 7K. NewsBank. Web. 23 Mar. 2010.

- ↑ Vought, Power Distribution

- 1 2 http://www.airtrans.endofnet.com/airtrans/umtatx060020796%20phase%20II%20vol5.pdf UMTA-TX-06-0020-79-6 AUTP Phase II Volume 5: System Operation

- ↑ http://www.voughtaircraft.com/heritage/special/html/sairt8.html Vought Heritage

- ↑ "Stovall Criticizes Postal Service." The Dallas Morning News. October 7, 1974.

- ↑ Terry Maxon. "American Airlines to get train system rolling." DALLAS MORNING NEWS 27 Sep. 1991, HOME FINAL, BUSINESS: 11D. NewsBank. Web. 22 Mar. 2010.

- ↑ "Cause of Crash Related." The Dallas Morning News. February 27, 1977.

- ↑ "Teen-ager Killed at D-FW Sought Job Earlier". The Dallas Morning News. September 17, 1977.

- ↑ Dallas Morning News, July 15, 1986 Missing or empty

|title=(help)

Bibliography

- Vought Aircraft Industries Retiree Club (Vought), "Airtrans"

- Austin Corbin, Jr., "Improving AIRTRANS for Urban Application", PRT IV, Volume 1, Group 1

- Ken Capps, "DFW International Airport Bids Farewell to Venerable Airport Train System", 21 June 2005

- AGT 1975, "Automated Guideway Transit : an assessment of PRT and other new systems", United States Congress, 1975

External links

- Vought Heritage Website

- Video of Airtrans system in operation

- View of Airtrans interior, 1982

- Photo of Airtrans exterior

- AIRTRANS URBAN tech. program Phase I final design, report no. UMTA-TX-06-0020-78-1

- UMTA-TX-06-0020-79-2 AUTP PHASE II Volume 1: CONTROL SYSTEMS IMPROVEMENTS

- UMTA-TX-06-0020-79-3 AUTP Phase II Volume 2 : IMPROVED PASSENGER COMMUNICATIONS

- UMTA-TX-06-0020-79-4 AUTP Phase II VOLUME 3: VEHICLE AND WAYSIDE SUBSYSTEMS

- UMTA-TX-06-0020-79-5 AUTP Phase II Volume 4: Vehicle Fabrication, tests and Demonstration

- UMTA-TX-06-0020-79-6 AUTP Phase II Volume 5: System Operation

- UMTA-TX-06-0020-79-7 AUTP Phase II Volume 6: SEVERE WEATHER

- UMTA-TX-06-0020-79-1 AUTP Phase II IRAN program