Wager Mutiny

The Wager Mutiny was the mutiny of the crew of HMS Wager after she was wrecked on a desolate island off the west coast of Chile in 1741. The ship was part of a squadron commanded by George Anson and bound to attack Spanish interests in the Pacific. Wager lost contact with the squadron whilst rounding Cape Horn, ran aground and wrecked on the west coast of Chile in May 1741. The main body of the crew mutinied against the captain, David Cheap, abandoned him and his loyal crew members, and returned in a modified open boat to England via the Strait of Magellan. Though most died on the journey, some survived, including the ring-leaders.

Captain Cheap and a smaller group, guided by natives, made their way north to an inhabited region of Chile. Most of them also died on their journey, but Cheap and three others survived and eventually returned to England in 1745, two years after the mutineers. The adventures of the crew of the Wager were a public sensation. They inspired many narratives written by survivors and others, including the novel The Unknown Shore (1959) by the celebrated 20th-century author Patrick O'Brian, who based his account on John Byron's memoir, published in 1768.

HMS Wager

Wager was originally an East India Company ship, an armed trading vessel built mainly to accommodate large cargoes of goods from the far east, but also capable of carrying significant firepower for self protection on the open seas. The vessel was bought by the Admiralty in 1739 to form part of a squadron under Commodore George Anson to attack Spanish interests on the Pacific west coast of South America.

Commodore Anson's squadron

The total squadron consisted of some 1,980 men (crew plus infantry), of which only 188 would survive the voyage. It was one of the most terrifying, challenging, heroic and adventurous circumnavigations of the globe ever completed. The squadron, including Wager, consisted of six warships and two victuallers (supply ships):[1]

- Centurion, the flagship (a fourth-rate ship of 1,005 tons, 60 guns and 400 men)

- Gloucester (866 tons, 50 guns, 300 men)

- Severn (683 tons, 50 guns, 300 men)

- Pearl (559 tons, 40 guns, 250 men)

- Wager (559 tons, 24 guns, 120 men)

- Tryal (201 tons, 8 guns, 70 men)

The two merchant vessels, which carried additional stores, were Anna (400 tons, 16-men), and Industry (200 tons). The squadron also comprised an additional 470 invalids and wounded soldiers from Chelsea hospital, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Cracherode. Most of these men were the first to die during the hardships of the voyage. Their inclusion in place of regular troops, was severely criticised as cruel and ineffective.[2][3][4][5]

Spithead to Staten Island

After taking 40 days to reach Funchal, the squadron replenished supplies of water, wood and fresh food before making the Atlantic crossing to Santa Catarina. Two weeks into this leg of the journey, the store ship Industry signaled to the Commodore that it required to speak to him. The Captain of Industry told Anson that his contract had been fulfilled and the ship needed to turn back for England. The stores from Industry were distributed amongst the remaining ships, with a large quantity of rum sent aboard Wager. Wager therefore held three main classes of cargo aboard (aside from her own allocated stores) namely; rum, trading goods for use with the local indigenous people up the coast of South America, which were to be traded for supplies required by the squadron and used to subvert Spanish rule; and finally, small-arms with powder and ball to arm shore-raiding parties.

Progress of the squadron to Staten Island on the Atlantic side of Cape Horn was remarkable only for the time that was taken to reach Funchal. At the time this was considered an inconvenience. But, this delay, coupled with the impressment of many sailors in England who had recently been at sea for some time, and had not fully restored their bodies to a fresh food diet, resulted in many of the men in the squadron dying of scurvy, due to lack of fresh citrus fruits or meats. The high contingent of invalids in the squadron, coupled with the outbreak of scurvy, meant that Anson's squadron was in poor condition for the arduous rounding of the Horn.[4][6][7]

Captain Dandy Kidd was moved from Wager to the Pearl, and Captain Murray moved to command Wager. Kidd died on the voyage after the squadron left Santa Catarina and before they reached the straits of Staten Island. On his death bed, he predicted success and riches for some, but death and devastating hardship for the crew of Wager. For the notoriously superstitious sailors on board Wager, this was awful news. As it turned out, it was an accurate prophecy.[8][9]

Kidd was replaced by Captain Murray, who left Wager to take command of Pearl. Lieutenant David Cheap was moved from the small sloop Tryal and promoted to Captain of Wager. Cheap was placed in command for the first time of a much larger vessel, crewed by sick and dispirited men who had not had the benefit of a long-serving captain. Cheap compounded these handicaps by denigrating the technical abilities of many of the officers, and being easily moved to fits of rage. In Cheap's favour, he was a capable seaman and navigator, a big man who feared nobody and, possibly most importantly, a loyal and determined officer.[10] The importance of the Wager and her role in the mission was pressed on Cheap by Anson as he assumed command; the squadron would draw on Wager's store of small arms and ammunition to attack shore bases along the west coast of Chile.

The rounding of the Horn

The delays of the voyage were most keenly felt when the squadron rounded the Horn. The weather conditions were atrocious; high sea states and contrary winds meant that progress west was very slow. Added to this was the deteriorating health of the crew: because of scurvy, few able-bodied seamen were available to work the ship and carry out running repairs to the continually battered rigging.[11]

After many weeks working westwards to clear the Horn, the squadron turned north when navigational reckoning suggested enough westerly had been made. At this time latitudinal determination was relatively easy with the use of a sextant; however, longitudinal determination was much harder to predict: it required accurate time-pieces or a good view of the stars on stable ground, neither of which were available to the squadron. Longitude was predicted by dead reckoning, an impossible task given the storm conditions, strong currents and length of time involved. The intention was to turn north only when Anson was reasonably certain that the Horn had been cleared.[12]

The result was nearly a complete disaster. In the middle of the night, the moon shone through the cloud for a few minutes, revealing to diligent sentinels aboard Anna towering waves breaking onto the Patagonian coastline. Anna fired guns and set up lights to warn the other ships of the danger. Without this sighting, the whole of Anson's squadron would have been wrecked, with the likely loss of all hands. This was a severe disappointment. The ships turned around and headed south again into huge seas and a foul wind. During one particularly severe night, Wager became separated from the rest of the squadron, and would never see it again.[13][14][15]

The wrecking of the Wager

As Wager, now alone, continued beating to the west, the question remained, when to turn north? Do it too early and the risk of running the ship aground was very high; which the crew already realized. But, they were severely depleted with scurvy - every day more victims were going down with the condition – and there was a shortage of seamen to handle the ship. The dilemma became contentious when Captain Cheap stated his intention to make for Socorro Island (now Guamblin Island). The gunner, John Bulkley, objected strongly to this proposal. He argued to make the secondary squadron rendezvous, the Island of Juan Fernandez, their primary destination, since it was not as close to the mainland as Socorro and was less likely to result in the wrecking the ship on a lee shore. Bulkley was recognized as probably the most capable seaman on the ship; as gunner, he had officer rank. Navigation was technically the responsibility of the master, Thomas Clark, but he, along with most of the officers on board, was held in thinly-disguised contempt by Cheap.[16]

Bulkley repeatedly tried to persuade Cheap to change his mind, arguing that the ship was in such poor condition that the crew's ability to carry the required sails to beat off a lee-shore or come to anchor was compromised, making Cheap's decision to head for Socorro too hazardous, especially given that the whole area was poorly charted. In the event Bulkley was to prove exactly correct, but Cheap refused to change course.[17][18][19][20]

On 13 May 1741, at 9 am, John Cummins, the carpenter, went forward to inspect the chain plates. Whilst there he thought he caught a fleeting glimpse of land to the west. The lieutenant, Baynes, was also on deck but he saw nothing, and the sighting was not reported. Baynes was later reprimanded at a Court Martial for failing to alert the Captain. The sighting of land to the west was thought to be impossible. But, Wager had entered a large uncharted bay, now called Golfo de Penas, and the land to the west was later to be called the Tres Montes Peninsula.

At 2 pm land was positively sighted to the west and northwest. All hands were mustered to make sail and turn the ship to the southwest. During the frantic operations which followed, Cheap fell down the quarterdeck ladder and dislocated his shoulder and was confined below. There followed a night of terrible weather, with the ship in a disabled and worn-out condition, which severely hampered efforts to get her clear of the bay. At 4:30 am, the ship struck rocks repeatedly, broke her tiller, and although still afloat was partially flooded. The invalids below who were too sick to move were drowned.[21][22]

Bulkley and another seaman, John Jones, began steering the ship with sail alone towards land, but later in the morning the ship struck again, this time fast.[23]

Shipwrecked on Wager Island

Wager had struck rocks on the coast of what would subsequently be known as Wager Island. Some of the crew broke into the spirit room and got drunk, armed themselves and began looting, dressing up in officers' clothes and fighting.[24] Aside from this, 140 other men and officers took to the boats and made it safely on shore; however, their prospects were desperate. They were shipwrecked far into the southern latitudes at the start of winter with little food, in an uncharted and desolate land with hardly any natural resources to sustain them. The crew were dangerously divided, with many blaming the captain for their predicament. On the following day, Friday 15 May, the ship bilged amidships, and many of the drunken crew still on board drowned. The only members of the crew left on board Wager were the boatswain, John King, and a few of his followers. King was a rebellious character, and, as events would prove, an extremely dangerous and difficult individual.[25]

Some of the ship's additional cargo was to prove useful. The crew used the Indian trading goods, mostly bolts of cloth, to add to improvised shelters. The other trinkets were largely useless, as were the small arms and ammunition and powder. No human enemies were nearby and little wildlife to hunt. The large quantity of extra rum was a problem, as many of the crew were perpetually drunk and very difficult to control.

Mutiny

Cast ashore in dreadful conditions, the crew of Wager were frightened and angry with their captain. Dissent and insubordination soon became increasingly common. King fired a four-pounder cannon from Wager at the captain's hut to induce someone to collect him and his mates once they began to fear for their safety on the wreck.[26]

Checking rebellious thoughts of the crew was British Naval law. Dissent by seamen or officers within the contemporary Royal Navy was met with a brutal and energetically-pursued vigour. Anyone found guilty of mutiny would be pursued for the rest of their lives across the globe. To be found guilty required very little insubordination by today’s standards. Once convicted, a man was rapidly sentenced to death by hanging from the yardarm.

The crew knew they were playing an extremely dangerous game, and worked to build a narrative to justify their rebellious actions. Full mutiny would likely not have occurred had the captain agreed to a plan of escape devised by Bulkley, who had the confidence of most men. He proposed that the carpenter, Cummins, would lengthen the longboat and convert it into a schooner which could accommodate more men. They would make their way home, via the Strait of Magellan, to Portuguese Brazil or the British Caribbean, and then home to England. The smaller boats, the barge and the cutter, would accompany the schooner and be important for inshore foraging work along their journey. Bulkley was skilful enough to give the plan a chance of success. Despite much prevarication, Captain Cheap finally would not agree to Bulkley's plan. He preferred to head north and try to catch-up with Anson's squadron.[27] If discipline for ordinary seamen was brutal, the officers were no better off. The importance of doing one's utmost to complete a mission was implicit.[28]

Aware that he had lost his ship, Cheap was in a predicament. He would automatically be subject to court martial and, if found guilty, he could be thrown out of the Navy and into a lifetime of poverty and isolation at best. At worst he could be found guilty of cowardice and executed by firing squad. This was demonstrated by the 1757 execution of Admiral John Byng. Cheap wanted to head north along the Chilean coast to rendezvous with Anson at Valdivia. He had concluded to exert unremitting zeal to try to salvage his first command. His warrant officers had warned him against some of his actions, which would reflect badly on him when the Admiralty investigated the loss of his ship.

This impasse led to the mutiny. The mutineers justified their actions based on other events, including the shooting by Cheap of a drunken insubordinate midshipman called Cozens. Cheap shot the man in the face at point blank range without warning, immediately after arriving at a reported altercation in a rage. Cozens was refused medical aid on the orders of the captain, and took ten days to die in agony.[17][29]

The carpenter continued modifying the boats for an as-yet undecided plan of escape, and until this was complete, outright mutiny would remain only a possibility. Once the schooner was ready, events would happen quickly. Bulkley set the wheels in motion by drafting the following letter for the captain to sign:

- "Whereas upon a General Consultation, it has been agreed to go from this Place through the Streights of Magellan, for the coast of Brazil, in our way for England: We do, notwithstanding, find the People separating into Parties, which must consequently end in the Destruction of the whole Body; and as also there have been great robberies committed on the Stores and every Thing is now at a Stand; therefore, to prevent all future Frauds and Animosoties, we are unanimously agreed to proceed as above-mentioned."[17][30]

Baynes was presented with the letter to read, after which doing so he made the following comment, which astonished the mutineers:

- "I cannot suppose the Captain will refuse the signing of it; but he is so self-willed, the best step we can take, is to put him under arrest for the killing of Mr. Cozens. In this case I will, with your approbation, assume command. Then our affairs will be concluded to the satisfaction of the whole company, without being any longer liable to the obstruction they now meet from the Captain's perverseness and chicanery."[31]

As expected, Cheap refused to sign Bulkley's letter. On 9 October, armed seamen entered Cheap's hut and bound him, claiming that he was now their prisoner and they were taking him to England for trial for the murder of Cozens. Lieutenant Hamilton of the Marines was also confined, the mutineers fearing his resistance to their plan, which confirmed the fact that this was indeed a mutiny. Cheap was completely taken aback, having no real idea how far things had gone.[32] The bound Cheap turned his attention to his Lieutenant, Baynes, terrifying him with the words, "Well 'Captain' Baynes! You will doubtless be called to account for this hereafter."[17][33]

The voyage of the Speedwell

At noon on Tuesday, 13 October 1741, the schooner, now named the Speedwell, got under sail with the cutter and barge in company. Cheap refused to go, and to the relief of the mutineers, he agreed to be left behind with two marines who were earlier shunned for stealing food. Everyone expected Cheap to die on Wager Island, making their arrival in England much easier to explain. Bulkley assumed this by writing in his journal that day, "this was the last I ever saw of the captain". In the event, both would make it back to England alive to tell their version of events, Cheap some two years after Bulkley.[26][34]

Initially the voyage got off to a bad start. After repeatedly splitting sails, the barge was sent back to Wager Island, where there were additional stores.[35] Two midshipmen, John Byron and Alexander Campbell, formed part of the nine who returned. Once back at Wager Island, they were greeted by Captain Cheap, who was delighted to hear of their wish to remain with him.[36] By the time Bulkley sailed back to Wager Island in search of the now missing barge and men, all had disappeared.[37]

The Speedwell and the cutter turned around and sailed south. The journey was arduous and food was in very short supply. On 3 November the cutter parted company; this was serious as she was needed for inshore foraging work. By now Bulkley was despairing of the men in the Speedwell. Most were in the advanced stages of starvation, exposed in a desperately cold, open boat, and had lapsed into apathy. Some days later they had good news, sighting the cutter and rejoining it. Soon after, at night, she broke loose from her consort's tow line and was wrecked on the coast. Of the eighty-one men who had departed about two weeks before, ten had already perished.[38]

As food began to run out, the situation became desperate. Ten men were picked out and forced to sign a paper consenting to being cast ashore on the uninhabited frozen bog-ridden southern coast of Chile, a virtual death sentence. Sixty men remained in the Speedwell. Eventually the improvised vessel entered the Strait of Magellan, in monstrous seas which threatened the boat with every wave. Men were dying from starvation regularly. Some days after exiting The Straits, the boat moved closer to land in order to take in water and hunt for food. Later, as the last of their supplies were being taken on board, Bulkley made sail, abandoning eight men on the desolate shore 300 miles short of Buenos Aires. Three of those he had abandoned made it back to England alive. Only thirty-three men remained in the Speedwell.[39]

Eventually, and after a brief stop at a Portuguese outpost on the River Plate, where the crew were fleeced by the locals for meagre provisions and cheated by a priest who disappeared with their fowling pieces (shotguns) on the promise of returning with game,[40] the Speedwell set sail once more. On 28 January 1742, it sighted the Rio Grande, southern Brazil, after a journey of over two-thousand miles in an open boat over fifteen weeks. Of the eighty-one men who set off from Wager Island, thirty arrived at Rio in a desperate condition.[41]

Captain Cheap's group

Twenty men remained on Wager Island after the departure of the Speedwell. Poor weather during October and November continued. One man died of exposure after being marooned for three days on a rock for stealing food. By December and the summer solstice, it was decided to launch the barge and the yawl and skirt up the coast 300 miles to an inhabited part of Chile. During bad weather, the yawl was overturned and lost, with the quartermaster drowned.[42]

There was not enough room for everyone in the barge, and four of the most helpless men, all marines, were left on the shore to fend for themselves. In his account, Campbell describes events thus:

- "The loss of the yawl was a great misfortune to us who belonged to her (being seven in number) all our clothes, arms, etc. being lost with her. As the barge was not capable of carrying both us and her own company, being in all seventeen men, it was determined to leave four of the Marines on this desolate place. This was a melancholy thing, but necessity compelled us to it. And as we were obliged to leave some behind us, the marines were fixed on, as not being of any service on board. What made the case of these poor men the more deplorable, was the place being destitute of seal, shellfish, or anything they could possibly live upon. The captain left them arms, ammunition, a frying pan, and several other necessaries."[43]

Fourteen men were left in the barge. After repeated failed attempts to round the headland, they decided to return to Wager Island and give up all hope of escape. The four stranded marines were looked for but had disappeared. Two months after leaving Wager Island, Captain Cheap's group returned. The thirteen survivors were close to death, and one man died of starvation shortly after arriving.[44]

Back at the island Captain Cheap took more food than the others and did less work. Fifteen days after returning to Wager Island, the men were visited by a party of Indians, astonished to find them. After some negotiation, with the surgeon speaking Spanish, they agreed to guide the castaways to a small Spanish settlement up the coast, using an overland route to avoid the peninsula. The castaways traded the barge for the journey. In his book, John Byron gives a detailed account of the journey to the village of Castro in Chile, as does Alexander Campbell. The ordeal took four months, during which another ten men died of starvation, exhaustion and fatigue. Marine Lieutenant Hamilton, Midshipmen Campbell, Midshipman Byron, and Captain Cheap were the only survivors.[43][45]

Bulkley & the Speedwell survivors return to England

The 30 mutineers had an anxious time before eventually securing passage to Rio de Janeiro on the brigantine Saint Catherine, which set sail on Sunday 28 March 1742. Once in Rio de Janeiro, internal and external diplomatic wrangling continually threatened to terminally complicate either their lives, or at least their return to England. John King did not help. He formed a violent gang that spent most of its time repeatedly terrorising his former shipmates on various pretexts. They moved to the opposite side of Rio to avoid King. After many episodes of fleeing their accommodations in terror of King and his gang (who referred to him as their 'commander'), Bulkley, Cummins and the cooper, John Young, eventually sought protection from the Portuguese authorities. Captain S W C Pack describes these events:

- "As soon as the ruffians had gone [Kings gang], the terrified occupants left their house via the back wall and fled into the country. Early the next morning they called on the consul and asked for protection. He readily understood that they were all in mortal peril from the mad designs of the boatswain [King] and placed them under protection and undertook to get them on board a ship where they could work their passage."[46]

They eventually secured passage to Bahia in the Saint Tubes, which set sail on 20 May 1742. They gladly left the boatswain John King behind to continue causing criminal havoc in Rio de Janeiro. On 11 September 1742, the Saint Tubes left Bahia bound for Lisbon, and from there they embarked in HMS Stirling Castle on 20 December bound for Spithead, England. They arrived on New Year's Day 1743, after an absence of more than two years.[47]

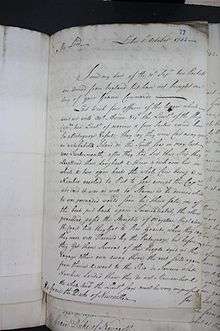

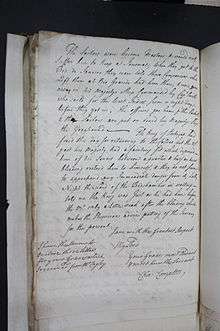

Events were also reported back to London from the British Consul in Lisbon, in a dispatch dated 1 October 1742 (see images):

- "Last week four officers of the Wager which went out with Mr Anson, viz the Lieutenant of the ship [illegible, Bulkley?], two lieutenants of marines and four sailors arrived here in a Portuguese vessel; they say they were cast away upon an uninhabited island in the South Seas in May last twelvemonth, after they had lost their ship they lengthened their longboat and threw a deck over her in which & two open boats the whole crew being 81 in number resorted to put to sea, except their Captain who said it was as well to starve as be drowned which he was persuaded would be their fate [this is a lie]. One of the boats put back again immediately [the barge], the others proceeded, sailed the Straights of Magellan, kept along the coast 'till they got to Rio Grande, where they say they were well received by the Portuguese. But before they got there several of the people died in the voyage, others ran away there [meaning Isaac Morris and others, this is also a lie]. The rest sailed again from thence and went to Rio de Janeiro, what numbers landed there they do not remember. The whole event the Lieutenant [Baynes] says must be very important for [Page 2] the sailors were become masters and would not suffer him to keep a journal. When they got to the Rio de Janeiro they're were lots of their companions who left them at Rio Grande had been there & were gone away in His Majesty's ship commanded by Captain Smith who sailed for the West Indies seven or eight days before they got in. The officers gone home of this Packet [i.e. HMS Stirling Castle] & the sailors are put on board His Majesty's ship the Greyhound."[48]

SWC Pack's book describes a similar report:

- "Arrival of some of the castaways from the loss of H.M.S. Wager in the South Pacific. Were well treated by Portuguese at Rio de Janeiro, but sailors were mutinous against their officers. King of Portugal has had another seizure and his departure for Caldas is postponed... etc."[49]

Lieutenant Baynes, in order to exonerate himself, rushed ahead of Bulkley and Cummins to the Admiralty in London and gave an account of what happened to Wager which reflected badly on Bulkley and Cummins but not himself. Baynes was a weak man and an incompetent officer, as was recorded by all those who provided a narrative of these events. As a result of Baynes' report, Bulkley and Cummins were detained aboard HMS Stirling Castle for two weeks whilst the Admiralty decided how to act. It was eventually decided to release them and defer any formal court martial proceedings until the return of either Commodore Anson or Captain Cheap. When Anson did return in 1744, it was decided that no trial would proceed until Cheap returned. Bulkley asked the Admiralty for permission to publish his journal. It responded that it was his business and he could do as he liked. He released a book containing his journal, but the initial reaction from some was that he should be hanged as a mutineer.[50]

Bulkley found employment when he assumed command of a forty-gun privateer Saphire. It was not long before Bulkley's competence and nerve found him success as he tricked his way around a superior force of French frigates which his vessel encountered when cruising. As a result, Bulkley found his successes being reported in popular London papers and gained some celebrity. He began thinking that it would not be long before the Admiralty would offer him the coveted command of a Royal Navy ship. On 9 April 1745, however, Cheap arrived back in England.[51]

Survivors of Captain Cheap's group return to England

By January 1742 (January 1743 in modern calendar, the year changed on 25th March in those days), as Bulkley was returning to Spithead, the four survivors of Cheap's group had spent seven months in Chaco. Nominal prisoners of the local governor, they were allowed to live with local hosts and were left unmolested. The biggest obstacle in Byron's efforts to return to England began firstly with the old lady who initially looked after him (and her two daughters) in the countryside before his move to the town itself. All of the ladies were fond of Byron and became extremely reluctant to let him leave, successfully getting the governor to agree to Byron staying with her for a few extra weeks. He finally left for Chaco, amidst many tears.[52] Once in Chaco, Byron was also offered the hand in marriage of the richest heiress in the town. Her beau said, although "her person was good, she could not be called a regular beauty", and this seems to have sealed her fate.[53] On 2 January 1743, the group left on a ship bound for Valparaiso. Cheap and Hamilton removed to St Jago, as they were officers who had preserved their commissions. Byron and Campbell were unceremoniously jailed.[43][54]

Campbell and Byron were confined in a single cell infested with insects and placed on a starvation diet. Many locals visited their cell, paying officials for the privilege of looking at the 'terrible Englishmen', people they had heard much about, but never seen before. But, the harsh conditions moved not only their curious visitors but also the sentry at their cell door, who allowed food and money to be taken to them. Eventually Cheap's whole group made it to Santiago, where things were much better. They stayed there on parole for the rest of 1743 and 1744. Exactly why becomes clearer in Campbell's account:

- "The Spaniards are very proud, and dress extremely gay; particularly the women, who spend a great deal of money upon their persons and houses. They are a good sort of people, and very courteous to strangers. Their women are also fond of gentlemen from other countries, and of other nations."[43]

After two years, the group were offered passage on a ship to Spain; they all agreed, except Campbell. He chose to travel overland with some Spanish naval officers to Buenos Aires and from there to connect to a different ship also bound for Spain. Campbell deeply resented Captain Cheap's giving him less money in a cash allowance than he gave to Hamilton and Byron.[55] Campbell was suspected to be edging toward marrying a Spanish colonial woman, which was against the rules of the British Navy at that time. Campbell was furious at this treatment. He wrote:

- "...the misunderstanding between me and the Captain, as already related, and since which we had not conversed together, induced me not to go home in the same ship with a man who had used me so ill; but rather to embark in a Spanish man-of-war then lying at Buenos Aires."[43]

On 20 December 1744, Cheap, Hamilton and Byron embarked on the French ship Lys,[56][57] which had to return to Valparaiso after springing a leak. On 1 March 1744 (modern 1745) Lys set out for Europe, and after a good passage round the Horn, she dropped anchor in Tobago in late June 1745. After managing to get lost and sail obliviously by night through the very dangerous island chain between Grenada and St Vincent, the ship headed for Puerto Rico. The crew was alarmed at seeing abandoned barrels from British warships, as Britain was now at war with France. After narrowly avoiding being captured off San Domingo, the ship made her way to Brest, arriving on 31 October 1744. After six months in Brest being virtually abandoned with no money, shelter, food or clothing, the destitute group embarked for England on a Dutch ship. On 9 April 1745 they landed at Dover, three men of the twenty who had left in the barge with Cheap on 15 December 1741.[58][59]

News of their arrival quickly spread to the Admiralty and Buckley. Cheap went directly to the Admiralty in London with his version of events. A court martial was duly organised. After all he had been through and survived, Bulkley was in danger for his life, and at risk of execution.[51]

Abandoned survivors of the Speedwell group return to England

Left by Bulkley at Freshwater Bay, in what is today the resort city of Mar del Plata,[60][61] were eight men who were alone, starving, sickly and in a hostile and remote country. After a month of living on seals killed with stones to preserve ball and powder, the group began the 300-mile trek north to Buenos Aires. Their greatest fear, correctly as it would transpire, were the Tehuelche nomads, who were known to live in the area. After a 60-mile trek north in two days, they were forced to return to Freshwater Bay because they were unable to locate any water resources. Once back they decided to wait for the wet season before making another attempt. By May they were starving for lack of food. They became more settled in Freshwater Bay, built a hut, tamed some puppies they took from a wild dog, and began raising pigs. One of the party spotted what they described as a 'tiger' reconnoitering their hut one night. Another sighting of a 'lion' shortly after this had the men hastily planning another attempt to walk to Buenos Aires (they actually saw a jaguar and a cougar).[62]

One day, when most of the men were out hunting, the group returned to find the two left behind to mind the camp had been murdered, the hut torn down, and all their possessions taken. Two other men who were hunting in another area disappeared, and their dogs made their way back to the devastated camp. The four remaining men left Freshwater Bay for Buenos Aires, accompanied by 16 dogs and two pigs.[63]

They did not get very far, and for the third time, were forced to return to Freshwater Bay. Shortly afterwards a large group of Indians on horseback surrounded them, took them all prisoner, and enslaved them. After being bought and sold four times, they were eventually taken to a local chieftain's camp. When he learned they were English and at war with the Spanish, he treated them better. By the end of 1743, after eight months as slaves, they eventually told the chief that they wanted to return to Buenos Aires. He agreed but refused to give up John Duck, who was mulatto. An English trader in Montevideo, upon hearing of their plight, put up the ransom of $270 for the other three and they were released.

On arrival in Buenos Aires, the governor put them in jail after they refused to convert to Catholicism. In early 1745 they were moved to the ship Asia, where they were to work as prisoners of war. After this they were thrown in prison again, chained, and placed on a bread and water diet for fourteen weeks, before a judge eventually ordered their release. Then Midshipman Alexander Campbell, another of Wager's crew, arrived in town.[63][64][65]

Midshipman Alexander Campbell's overland trek to Buenos Aires

On 20 January 1745 Campbell and four Spanish naval officers set out across South America from Valparaiso to Buenos Aires. Using mules, the party trekked into the high Andes, where they faced precipitous mountains, severe cold and, at times, serious altitude sickness. First a mule slipped on an exposed path and was dashed onto rocks far below, then two mules froze to death on a particularly horrendous night of blizzards, and an additional 20 died of thirst or starvation on the remaining journey. After seven weeks travelling, the party eventually arrived in Buenos Aires.[43][66]

Campbell and the Freshwater Bay survivors return to England

It took five months for Alexander Campbell to get out of Buenos Aires, where he was twice confined in a fort for periods of several weeks. Eventually the governor sent him to Montevideo, which was just 100 miles across the Río de la Plata. It was here that the three Freshwater Bay survivors, Midshipman Isaac Morris, Seaman Samuel Cooper and John Andrews were languishing as prisoners of war aboard the Spanish ship Asia, along with sixteen other English sailors from another ship. Campbell had finally converted to Catholicism, which helped him. While his fellow shipmates were treated harshly and confined aboard the Asia, Campbell wined and dined with various captains on the social circuit of Montevideo.[43][67]

All four Wager survivors departed for Spain in the Asia at the end of October 1745, but the passage was not without incident. Having been at sea three days, eleven Indian crew on board mutinied against their barbaric treatment by the Spanish officers. They killed twenty Spaniards and wounded another twenty before briefly taking control of the ship (which had a total crew of over five hundred). Eventually the Spaniards worked to reassert control and through a 'lucky shot', according to Morris, they killed the Indian chief Orellana dead. His followers all jumped overboard rather than submit to Spanish retribution.[64][68]

The Asia dropped anchor at the port Corcubion, near Cape Finisterre on 20 January 1746. The authorities chained together Morris, Cooper and Andrews and put them in jail. Campbell went to Madrid for questioning. After four months held captive in awful conditions, the three Freshwater Bay survivors were eventually released to Portugal, from where they sailed for England, arriving in London on 5 July 1746. Bulkley had to confront men he assumed had died on a desolated coastline thousands of miles away.[69]

Campbell's insistence that he had not entered the service of the Spanish Navy, as Cheap and Byron had believed, was apparently confirmed when he arrived in London during early May 1746, shortly after Cheap. Campbell went straight to the Admiralty, where he was promptly dismissed from the service for his change in religion. His hatred for Cheap had, if anything, intensified. After all he had been through, he completes his account of this incredible story thus:

- "Most of the hardships I suffered in following the fortunes of Captain Cheap were the consequence of my voluntary attachment to that gentleman. In reward for this the Captain has approved himself the greatest Enemy I have in the world. His ungenerous Usage of me forced me to quit his Company, and embark for Europe in a Spanish ship rather than a French one."[43][69]

Court martial into the loss of Wager

Proceedings for a full court martial to inquire into the loss of Wager were initiated once Cheap had returned and made his report to the Admiralty. All Wager survivors were ordered to report aboard HMS Prince George at Spithead for the court martial. Bulkley on hearing this reacted in his typical style of being overly clever and devious. He arranged to dine with the Deputy Marshal of the Admiralty (the enforcing officer of the Royal Navy command) but kept his true identity concealed.

Bulkley wrote about his prepared conversation with the Deputy Marshal at the Paul's Head Tavern in Cateaton Street:

- "Desiring to know his opinion in regard to the Officers of the Wager, as their Captain was come home; for that I had a near relation which was an Officer that came in the long-boat from Brazil, and it would give me concern if he would suffer: His answer was that he believ'd that we should be hang'd [sic]. To which I replied, for God's Sake for what, for not being drown'd? And is a Murderer at last come home to their Accuser? I have carefully perused the Journal, and can't conceive that they have been guilty of Piracy, Mutiny, nor any Thing else to deserve it. It looks to me as if their Adversaries have taken up arms against the Power of the Almighty, for delivering them."[70]

At which point the Marshal responded:

- "Sir, they have been guilty of such things to Captain Cheap whilst a Prisoner, that I believe the Gunner and Carpenter will be hang'd if no Body else."[70]

Bulkley told the Marshal of his true identity, who immediately arrested him. Upon arrival aboard Prince George, Bulkley sent some of his friends to visit Cheap to gauge his mood and intentions. Their report gave Bulkley little comfort. Cheap was in a vindictive frame of mind, telling them:

- Gentlemen, I have nothing to say for nor against Villains, until the Day of Tryal, and then it is not in my Power to be off from hanging them."[71]

Upon securing the main players, trial was set for Tuesday 15 April 1746, presided by Vice Admiral of the Red Squadron James Steuart. Much of what happened on the day land was first sighted off Patagonia as recounted here came out in sworn testimonies, with statements from Cheap, Byron, Hamilton, Bulkley, Cummins and King (who had also returned to England, under unknown circumstances) and a number of other crew members.

Cheap, although keen to charge those who abandoned him in the Speedwell with mutiny, decided not to make any accusations when it was suggested to him that any such claims would lead to his being accused of murdering Midshipman Cozens. None of the witnesses was aware at this point that the Admiralty had decided not to examine events after the ship foundered as part of the scope of the court martial proceedings.

After testimony and questioning, the men were all were promptly acquitted of any wrong-doing, except for Lieutenant Baynes. He was admonished for not reporting the carpenter's sighting of land to the west to the captain, or letting go the anchor when ordered.

Aftermath

The mutineers argued that, since their pay stopped on the day their vessel was wrecked, they were no longer under naval law. Captain S W C Pack, in his book about the mutiny, describes this and the Admiralty's decision not to investigate events after the Wager was lost in more detail:

- "Their Lordships knew that a conviction of mutiny would be unpopular with the country. Things were bad with the Navy in April 1746. Their Lordships were out of favour. One of the reasons for this was their harsh treatment of Admiral Vernon, a popular figure with the public... The defence that the Mutineers had was that as their wages automatically stopped when the ship was lost, they were no longer under naval law. Existence of such a misconception could lead, in time of enemy action or other hazard, to anticipation that the ship was already lost. Anson realised the danger and corrected this misconception. As Lord Commissioner he removed any further doubt in 1747. An Act was passed "for extending the discipline of the Navy to crews of his majesty's ships, wrecked lost or taken, and continuing to receive wages upon certain conditions... The survivors of the Wager were extremely lucky not to be convicted of mutiny and owe their acquittal not only to the unpopularity of the Board, but to the strength of public opinion, to the fact that their miraculous escapes had captured the public fancy."[72]

Captain Cheap was promoted to the distinguished rank of post captain and appointed to command the forty-gun ship Lark, demonstrating that the Admiralty considered his many faults secondary to his steadfast loyalty and sense of purpose. He captured a valuable prize soon after, which allowed him to marry in 1748. He died in 1752. His service records, reports, will and death are recorded in the National Archives.[73][74]

Midshipman John Byron was promoted to the rank of master and commander, and appointed to command the twenty-gun ship Syren. He eventually rose to the rank of vice admiral. Byron had a varied and significant active service history which included a circumnavigation of the globe. He married in 1748 and raised a family. His grandson George Gordon Byron became a famous poet. He died in 1786.

Robert Baynes' service records exist from prior to the sailing of Anson's squadron.[75] Upon his return to England after the Wager affair, he never served at sea again. Instead, in February 1745, before the court martial, he was given a position onshore running a naval store yard in Clay near the Sea, Norfolk.[76] Apart from some reports of thieving from his yard, his life did not create other records.[77] He remained in this capacity until his death in 1758.[78][79]

Shortly after the court martial, John Bulkley was offered command of the cutter Royal George, which he declined, thinking her "too small to keep to the sea". He was right in his assessment, as the vessel subsequently foundered in the Bay of Biscay, with the loss of all hands.[17][80]

Alexander Campbell completes his narrative of the Wager affair by denying he had entered the service of the Spanish Navy; however, in the same year his book was published, a report was made against him. Commodore Edward Legge (formerly captain of HMS Severn in Anson's original squadron) reported that whilst cruising in Portuguese waters, he encountered a certain Alexander Campbell in port, formerly of the Royal Navy and the Wager, enlisting English seamen and sending them overland to Cadiz to join the Spanish service.[81]

Further reading

- Rear Admiral C.H. Layman: The Wager Disaster: Mayhem, Mutiny and Murder in the South Seas. Unicorn Press, London 2015. ISBN 978-191-006-550-1

References

- ↑ Williams, Glyn (1999), p. 15

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), p. 13

- ↑ Williams, Glyn (1999), p.21

- 1 2 Walter, Richard (1749) p.7

- ↑ Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the Western Hemisphere, 1492 to the Present, Volume 1, David Marley, p. 388

- ↑ Williams, Glyn (1999), p. 29 & p. 45

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), p. 15

- ↑ Williams, Glyn (1999), p. 35

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), p. 21

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), p. 20

- ↑ Bulkley, John; Cummins, John (1743), pp. 10–11

- ↑ Walter, Richard (1749) pp. 81–82

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), pp. 30–38

- ↑ Williams, Glyn (1999), pp. 45–46

- ↑ Byron, John (1768), pp. 3–4

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), p. 35

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bulkley, John; Cummins, John (1743), pp. 12–14

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), p. 40

- ↑ Williams, Glyn (1999), pp. 38–41

- ↑ Byron, John (1768), pp. 4–5

- ↑ Bulkley, John; Cummins, John (1743), pp. 15–20

- ↑ Byron, John (1768), pp. 7–12

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), pp. 44–45

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), p. 47 & p. 53

- ↑ Byron, John (1768), pp. 16–19

- 1 2 Pack, S (1964), p. 54

- ↑ Bulkley, John; Cummins, John (1743), p. 15–20

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), pp. 80–82

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), p. 62

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), p. 87–88

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), p. 88

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), pp. 96–97

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), p. 98

- ↑ Byron, John (1768), p. 45

- ↑ Bulkley, John; Cummins, John (1743), p.108

- ↑ Byron, John (1768), p. 46

- ↑ Bulkley, John; Cummins, John (1743), p. 109

- ↑ Bulkley, John; Cummins, John (1743), pp. 110–121

- ↑ Bulkley, John; Cummins, John (1743), pp. 122–126

- ↑ Bulkley, John; Cummins, John (1743), pp. 166–167

- ↑ Bulkley, John; Cummins, John (1743), pp. 169–170

- ↑ Byron, John (1768), pp. 51–64

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Campbell, Alexander (1747)

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), pp. 140–146

- ↑ Byron, John (1768), pp. 71–124

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), p. 167

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), pp. 167–172

- ↑ Records assembled by the State Paper Office [National Archives SP 89/42]

- ↑ Records assembled by the State Paper Office SP 89/42

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), p. 222

- 1 2 Pack, S (1964), p. 223

- ↑ Byron, John (1768), p. 146

- ↑ Byron, John (1768), p.147

- ↑ Byron, John (1768), p. 155

- ↑ British Consul, Lisbon "A Castres, Lisbon. Requests payment for a bill drawn by Captain David Cheap late of the Wager" ADM 106/988/106

- ↑ Byron, John (1768), p. 176

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), p. 206

- ↑ Byron, John (1768), p. 189

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), p. 211

- ↑ Vignati, Milcíades Alejo (1956), p.86

- ↑ Bulkeley, John; Cummins, John; Byron, John; Gurney, Alan (2004) p. 237

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), pp. 190–193

- 1 2 Pack, S (1964), pp. 194–198

- 1 2 Byron, John; Morris, Isaac (1913)

- ↑ Morris, Isaac (1751)

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), p. 213

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), p. 214

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), pp. 217–218

- 1 2 Pack, S (1964), p. 219

- 1 2 Pack, S (1964), p. 224

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), p. 225

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), p. 246

- ↑ Admiralty Service Records, David Cheap, 1st Lieutenant ADM 6/15/209

- ↑ Admiralty Archive: Will of Captain David Cheap PROB 11/797

- ↑ Admiralty Service Records: Robert Baynes, Lieutenant ADM 6/15/218

- ↑ Robert Baynes "takes charge of the Rye's stores on the orders of George Goldsworth" ADM 106/1003/52

- ↑ Robert Baynes, "Robert Baynes, men charged with thieving from his yard" ADM 106/1003/141

- ↑ Robert Baynes, Records of the Prerogative Court of Canterbury PROB 31/416/337

- ↑ Robert Baynes, death recorded by Admiralty ADM 354/160/116

- ↑ Pack, S (1964), p.244

- ↑ Williams, Glyn (1999), pp.101–102

- Bulkeley, John; Cummins, John. A Voyage to the South-Seas in the Years 1740-1. London: Jacob Robinson, 1743. Second edition, with additions, London (1757)

- Bulkeley, John; Cummins, John; Byron, John; Gurney, Alan. The Loss of the Wager: The Narratives of John Bulkeley and the Hon. John Byron, Boydell Press (2004). ISBN 1-84383-096-5

- Byron, John. Narrative of the Hon. John Byron; Being an Account of the Shipwreck of The Wager; and the Subsequent Adventures of Her Crew, 1768. Second edition, 1785.

- Byron, John; Morris, Isaac. The Wreck of The Wager and subsequent Adventures of her Crew, Narritives of The Hon. John Byron and his fellow midshipman Isaac Morris. 1913. Blackie & Son Ltd., London.

- Campbell, Alexander. The sequel to Bulkeley and Cummins's voyage to the South-seas. London, W. Owen (1747)

- Layman, Rear Admiral C. H. (2015). The Wager Disaster: Mayhem, Mutiny and Murder in the South Seas. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-1910065501.

- Morris, Isaac. A Narrative of the Dangers and Distresses Which Befel Isaac Morris, and Seven More of the Crew, Belonging to the Wager Store-Ship, Which Attended Commodore Anson, in His Voyage to the South Sea: Containing an Account of Their Adventures. London: S. Birt, 1752.

- Pack, S. W. C. (1964). The Wager Mutiny. A. Redman. OCLC 5152716.

- (Spanish) Vignati, Milcíades Alejo: Viajeros, obras y documentos para el estudio del hombre americano: Obras y documentos para el estudio del hombre americano. Editorial Coni, Buenos Aires, 1956, p. 86

- Walter, Richard (1749), A voyage round the world, in the years 1740-44 (5th Edition). John and Paul Knapdon, London

- Williams, Glyn (1999). The Prize of All the Oceans. Viking, New York. ISBN 0-670-89197-5