Camino de Santiago

| Route of Santiago de Compostela | |

|---|---|

| Name as inscribed on the World Heritage List | |

| |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iv, vi |

| Reference | 669 |

| UNESCO region | Europe and North America |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1993 (17th Session) |

The Camino de Santiago (Latin: Peregrinatio Compostellana, Galician: Camiño de Santiago), also known by the English names Way of St. James, St. James's Way, St. James's Path, St. James's Trail, Route of Santiago de Compostela,[1] and Road to Santiago,[2] is the name of any of the pilgrimage routes, known as pilgrim ways, to the shrine of the apostle St. James the Great in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Galicia in northwestern Spain, where tradition has it that the remains of the saint are buried. Many follow its routes as a form of spiritual path or retreat for their spiritual growth. It is also popular with hiking and cycling enthusiasts as well as organized tours.

Major Christian pilgrimage route

The Way of St. James was one of the most important Christian pilgrimages during the Middle Ages, together with those to Rome and Jerusalem, and a pilgrimage route on which a plenary indulgence could be earned;[3] other major pilgrimage routes include the Via Francigena to Rome and the pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

Legend holds that St. James's remains were carried by boat from Jerusalem to northern Spain, where he was buried in what is now the city of Santiago de Compostela. (The name Santiago is the local Galician evolution of Vulgar Latin Sancti Iacobi, "Saint James".)

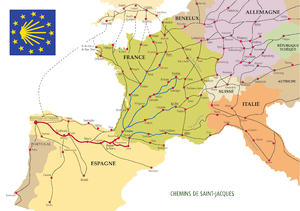

The Way can take one of dozens of pilgrimage routes to Santiago de Compostela. Traditionally, as with most pilgrimages, the Way of Saint James began at one's home and ended at the pilgrimage site. However, a few of the routes are considered main ones. During the Middle Ages, the route was highly travelled. However, the Black Death, the Protestant Reformation, and political unrest in 16th century Europe led to its decline. By the 1980s, only a few pilgrims per year arrived in Santiago. Later, the route attracted a growing number of modern-day pilgrims from around the globe. In October 1987, the route was declared the first European Cultural Route by the Council of Europe; it was also named one of UNESCO's World Heritage Sites.

Whenever St. James's Day (25 July) falls on a Sunday, the cathedral declares a Holy or Jubilee Year. Depending on leap years, Holy Years occur in 5, 6, and 11 year intervals. The most recent were 1982, 1993, 1999, 2004, and 2010. The next will be 2021, 2027, and 2032.[4]

History

The pilgrimage to Santiago has never ceased from the time of the discovery of St. James's remains, though there have been years of fewer pilgrims, particularly during European wars.

Pre-Christian history

The main pilgrimage route to Santiago follows an earlier Roman trade route, which continues to the Atlantic coast of Galicia, ending at Cape Finisterre. Although it is known today that Cape Finisterre, Spain's westernmost point, is not the westernmost point of Europe (Cabo da Roca in Portugal is farther west), the fact that the Romans called it Finisterrae (literally the end of the world or Land's End in Latin) indicates that they viewed it as such. At night, the Milky Way overhead seems to point the way, so the route acquired the nickname "Voie lactée" – the Milky Way in French.[5]

Scallop symbol

The scallop shell, often found on the shores in Galicia, has long been the symbol of the Camino de Santiago. Over the centuries the scallop shell has taken on mythical, metaphorical and practical meanings, even if its relevance may actually derive from the desire of pilgrims to take home a souvenir.

Two versions of the most common myth about the origin of the symbol concern the death of Saint James, who was martyred by beheading in Jerusalem in 44 AD. According to Spanish legends, he had spent time preaching the gospel in Spain, but returned to Judaea upon seeing a vision of the Virgin Mary on the bank of the Ebro River.[6][7]

- Version 1: After James's death, his disciples shipped his body to the Iberian Peninsula to be buried in what is now Santiago. Off the coast of Spain, a heavy storm hit the ship, and the body was lost to the ocean. After some time, however, it washed ashore undamaged, covered in scallops.

- Version 2: After James's death his body was transported by a ship piloted by an angel, back to the Iberian Peninsula to be buried in what is now Santiago. As the ship approached land, a wedding was taking place on shore. The young groom was on horseback, and on seeing the ship approaching, his horse got spooked, and horse and rider plunged into the sea. Through miraculous intervention, the horse and rider emerged from the water alive, covered in seashells.[8]

The scallop shell also acts as a metaphor. The grooves in the shell, which meet at a single point, represent the various routes pilgrims traveled, eventually arriving at a single destination: the tomb of James in Santiago de Compostela. The shell is also a metaphor for the pilgrim: As the waves of the ocean wash scallop shells up onto the shores of Galicia, God's hand also guides the pilgrims to Santiago.

As the symbol of the Camino de Santiago, the shell is seen very frequently along the trails. The shell is seen on posts and signs along the Camino in order to guide pilgrims along the way. The shell is even more commonly seen on the pilgrims themselves. Wearing a shell denotes that one is a traveler on the Camino de Santiago. Most pilgrims receive a shell at the beginning of their journey and either attach it to them by sewing it onto their clothes or wearing it around their neck or by simply keeping it in their backpack.[9]

The scallop shell also served practical purposes for pilgrims on the Camino de Santiago. The shell was the right size for gathering water to drink or for eating out of as a makeshift bowl.

The pilgrim's staff is a walking stick used by pilgrims to the shrine of Santiago de Compostela in Spain.[10] Generally, the stick has a hook on it so that something may be hung from it, and may have a crosspiece on it.[11]

Medieval route

The pilgrim route is a very good thing, but it is narrow. For the road which leads us to life is narrow; on the other hand, the road which leads to death is broad and spacious. The pilgrim route is for those who are good: it is the lack of vices, the thwarting of the body, the increase of virtues, pardon for sins, sorrow for the penitent, the road of the righteous, love of the saints, faith in the resurrection and the reward of the blessed, a separation from hell, the protection of the heavens. It takes us away from luscious foods, it makes gluttonous fatness vanish, it restrains voluptuousness, constrains the appetites of the flesh which attack the fortress of the soul, cleanses the spirit, leads us to contemplation, humbles the haughty, raises up the lowly, loves poverty. It hates the reproach of those fuelled by greed. It loves, on the other hand, the person who gives to the poor. It rewards those who live simply and do good works; And, on the other hand, it does not pluck those who are stingy and wicked from the claws of sin.

The earliest records of visits paid to the shrine dedicated to St. James at Santiago de Compostela date from the 9th century, in the time of the Kingdom of Asturias and Galicia. The pilgrimage to the shrine became the most renowned medieval pilgrimage, and it became customary for those who returned from Compostela to carry back with them a Galician scallop shell as proof of their completion of the journey. This practice was gradually extended to other pilgrimages.

The earliest recorded pilgrims from beyond the Pyrenees visited the shrine in the middle of the 11th century, but it seems that it was not until a century later that large numbers of pilgrims from abroad were regularly journeying there. The earliest records of pilgrims that arrived from England belong to the period between 1092 and 1105. However, by the early 12th century the pilgrimage had become a highly organized affair.

One of the great proponents of the pilgrimage in the 12th century was Pope Callixtus II, who started the Compostelan Holy Years.[12] The official guide in those times was the Codex Calixtinus. Published around 1140, the 5th book of the Codex is still considered the definitive source for many modern guidebooks. Four pilgrimage routes listed in the Codex originate in France and converge at Puente la Reina. From there, a well-defined route crosses northern Spain, linking Burgos, Carrión de los Condes, Sahagún, León, Astorga, and Compostela.

The daily needs of pilgrims on their way to and from Compostela were met by a series of hospitals and contributed to the development of the idea itself, some Spanish towns still bearing the name; Hospital de Órbigo. The hospitals were often staffed by Catholic orders and under royal protection. Donations were encouraged but many poorer pilgrims had little clothes and poor health often barely getting to the next hospital. Romanesque architecture, a new genre of church architecture, design was affected by the crowds of the devout leading to the development of with massive archways. There was also the sale of the now-familiar paraphernalia of tourism, such as badges and souvenirs. Since the Christian symbol for James the Greater was the scallop shell, many pilgrims wore one as a sign to anyone on the road that they were a pilgrim. This gave them privileges to sleep in churches and ask for free meals, but also attempted to ward off thieves with limited success, thus needing another hospital in the next town. Pilgrims often prayed to Saint Roch whose numerous depictions with the Cross of St James can still be seen along the Way even today.

The pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela was possible because of the protection and freedom provided by the Kingdom of France, where the majority of pilgrims originated. Enterprising French (including Gascons and other peoples not under the French crown) settled in towns along the pilgrimage routes, where their names appear in the archives. The pilgrims were tended by people like Domingo de la Calzada, who was later recognized as a saint.

Pilgrims walked the Way of St. James, often for months and sometime years at a time, to arrive at the great church in the main square of Compostela and pay homage to St. James. Many arrived with very little due to illness or robbery or both. Traditionally pilgrims lay their hands on the pillar just inside the doorway of the cathedral, and so many now have done it has visibly worn away the stone.[13]

The popular Spanish name for the astronomical Milky Way is El Camino de Santiago. According to a common medieval legend, the Milky Way was formed from the dust raised by traveling pilgrims.[14] Compostela itself means "field of stars". Another origin for this popular name is Book IV of the Book of Saint James which relates how the saint appeared in a dream to Charlemagne, urging him to liberate his tomb from the Moors and showing him the direction to follow by the route of the Milky Way.

As penance

The Church employed a system of rituals to atone for temporal punishment due to sins known as penance. According to this system, pilgrimages were a suitable form of expiation for some temporal punishment, and they could be used as acts of penance for those who were guilty of certain crimes. As noted in the Catholic Encyclopedia:[15]

In the registers of the Inquisition at Carcassone...we find the four following places noted as being the centres of the greater pilgrimages to be imposed as penances for the graver crimes: the tomb of the Apostles at Rome, the shrine of St. James at Compostella [sic], St. Thomas' body at Canterbury, and the relics of the Three Kings at Cologne.

There is still a tradition in Flanders of pardoning and releasing one prisoner every year[16] under the condition that this prisoner walks to Santiago wearing a heavy backpack, accompanied by a guard.

Enlightenment Era

During the war of American Independence, John Adams was ordered by Congress to go to Paris to obtain funds for the cause. His ship started leaking and he disembarked with his two sons in Finisterre in 1779. From there he proceeded to follow the Way of St. James in the reverse direction of the pilgrims' route, in order to get to Paris overland. He did not stop to visit Santiago, which he later came to regret. In his autobiography, Adams described the customs and lodgings afforded to St. James's pilgrims in the 18th century and he recounted the legend as he learned it:[17]

I have always regretted that We could not find time to make a Pilgrimage to Saintiago de Compostella. We were informed, ... that the Original of this Shrine and Temple of St. Iago was this. A certain Shepherd saw a bright Light there in the night. Afterwards it was revealed to an Archbishop that St. James was buried there. This laid the Foundation of a Church, and they have built an Altar on the Spot where the Shepherd saw the Light. In the time of the Moors, the People made a Vow, that if the Moors should be driven from this Country, they would give a certain portion of the Income of their Lands to Saint James. The Moors were defeated and expelled and it was reported and believed, that Saint James was in the Battle and fought with a drawn Sword at the head of the Spanish Troops, on Horseback. The People, believing that they owed the Victory to the Saint, very cheerfully fulfilled their Vows by paying the Tribute. ...Upon the Supposition that this is the place of the Sepulchre of Saint James, there are great numbers of Pilgrims, who visit it, every Year, from France, Spain, Italy and other parts of Europe, many of them on foot.

Adams' great-grandson, the historian Henry Adams visited Leon, among other Spanish cities, during his trip through Europe as a youth, although he did not follow the entire pilgrimage route.[18] Another Enlightenment-era traveler on the pilgrimage route was the naturalist Alexander von Humboldt.

Modern-day pilgrimage

Today, hundreds of thousands (over 200,000 in 2014)[19] of Christian pilgrims and many others set out each year from their front doorsteps or from popular starting points across Europe, to make their way to Santiago de Compostela. Most travel by foot, some by bicycle, and a few travel as some of their medieval counterparts did, on horseback or by donkey (for example, the British author and humorist Tim Moore). In addition to those undertaking a religious pilgrimage, many are hikers who walk the route for other reasons: travel, sport, or simply the challenge of weeks of walking in a foreign land. Also, many consider the experience a spiritual adventure to remove themselves from the bustle of modern life. It serves as a retreat for many modern "pilgrims".[20]

Routes

The oldest route to Santiago de Compostela, first taken in the 9th century, is referred to as the Original Way or Camino Primitivo, which begins in Oviedo.[21]

Pilgrims on the Way of St. James walk for weeks or months to visit the city of Santiago de Compostela. Some Europeans begin their pilgrimage on foot from the very doorstep of their homes, just as their medieval counterparts did.

They follow many routes (any path to Santiago can be considered a pilgrim's path), but the most popular is Via Regia and its last part, the French Way (Camino Francés). Historically, due to the Codex Calixtinus, most of the pilgrims came from France: typically from Arles, Le Puy, Paris, and Vézelay; some from Saint Gilles. Cluny, site of the celebrated medieval abbey, was another important rallying point for pilgrims and, in 2002, it was integrated into the official European pilgrimage route linking Vézelay and Le Puy.

The Spanish consider the Pyrenees a starting point. Along the French border, common starting points are Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port or Somport, on the French side of the Pyrenees, and Roncesvalles or Jaca, on the Spanish side. (The distance from Roncesvalles to Santiago de Compostella through León is about 800 km.). An alternative is the Northern Route nearer the Spanish coast along the Bay of Biscay, which was first used by pilgrims to avoid travelling through the territories occupied by the Muslims in the Middle Ages.

Another popular route is the Portuguese Way, which starts either at the cathedral in Lisbon (for a total of about 610 km) or at the cathedral in Porto in the north of Portugal (for a total of about 227 km), crossing into Galicia at Valença.[22]

Accommodation

In Spain, France and Portugal, pilgrim's hostels with beds in dormitories dot the common routes, providing overnight accommodation for pilgrims who hold a credencial (see below). In Spain this type of accommodation is called a refugio or albergue, both of which are similar to youth hostels or hostelries in the French system of gîtes d'étape.

Staying at pilgrims' hostels, known as albergues, usually costs between 6 and 10 euros per night per bed, although a few hostels known as donativos operate on voluntary donations. (Municipal albergues cost 6 euros, while private albergues generally cost between 10 and 15 euros per night.) Pilgrims are usually limited to one night's accommodation and are expected to leave by eight in the morning to continue their pilgrimage.

Hostels may be run by the local parish, the local council, private owners or pilgrims' associations. Occasionally these refugios are located in monasteries, such as the one run by monks in Samos, Spain and the one in Santiago de Compostela.

The final hostel on the route is the famous Hostal de los Reyes Catolicos, which lies across the plaza from the Cathedral of Santiago de Campostela. It was originally constructed by Ferdinand and Isabel, the Catholic Monarchs. Today it is a luxury 5-star Parador hotel, which still provides free services to a limited number of pilgrims daily.

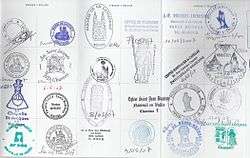

Credencial or pilgrim's passport

Most pilgrims carry a document called the credencial, purchased for a few euros from a Spanish tourist agency, a church or parish house on the route, a refugio, their church back home, or outside of Spain through the national St. James organization of that country. The credencial is a pass which gives access to inexpensive, sometimes free, overnight accommodation in refugios along the trail. Also known as the "pilgrim's passport", the credencial is stamped with the official St. James stamp of each town or refugio at which the pilgrim has stayed. It provides pilgrims with a record of where they ate or slept, and serves as proof to the Pilgrim's Office in Santiago that the journey was accomplished according to an official route, and thus that the pilgrim qualifies to receive a compostela (certificate of completion of the pilgrimage).

Most often the stamp can be obtained in the refugio, cathedral, or local church. If the church is closed, the town hall or office of tourism can provide a stamp, as can nearby youth hostels or private St. James addresses. Many of the small restaurants and cafes along the Camino also provide stamps. Outside Spain, the stamp can be associated with something of a ceremony, where the stamper and the pilgrim can share information. As the pilgrimage approaches Santiago, many of the stamps in small towns are self-service due to the greater number of pilgrims, while in the larger towns there are several options to obtain the stamp.

Compostela

The compostela is a certificate of accomplishment given to pilgrims on completing the Way. To earn the compostela one needs to walk a minimum of 100 km or cycle at least 200 km. In practice, for walkers, the closest convenient point to start is Sarria, as it has good bus and rail connections to other places in Spain. Pilgrims arriving in Santiago de Compostela who have walked at least the last 100 km, or cycled 200 km to get there (as indicated on their credencial), and who state that their motivation was at least partially religious are eligible for the compostela from the Pilgrim's Office in Santiago. At the Pilgrim's Office the credencial is examined for stamps and dates, and the pilgrim is asked to state whether the motivation in traveling the Camino was "religious", "religious and other", or "other". In the case of "religious" or "religious and other" a compostela is available; in the case of "other" there is a simpler certificate in Spanish.

The compostela has been indulgenced since the Early Middle Ages and remains so to this day, during Holy Years.[23] It reads:

CAPITULUM huius Almae Apostolicae et Metropolitanae Ecclesiae Compostellanae sigilli Altaris Beati Jacobi Apostoli custos, ut omnibus Fidelibus et Perigrinis ex toto terrarum Orbe, devotionis affectu vel voti causa, ad limina Apostoli Nostri Hispaniarum Patroni ac Tutelaris SANCTI JACOBI convenientibus, authenticas visitationis litteras expediat, omnibus et singulis praesentes inspecturis, notum facit : (Latin version of name of recipient)

Hoc sacratissimum Templum pietatis causa devote visitasse. In quorum fidem praesentes litteras, sigillo ejusdem Sanctae Ecclesiae munitas, ei confero.

Datum Compostellae die (day) mensis (month) anno Dei (year)

Canonicus Deputatus pro Peregrinis

English translation:

The CHAPTER of this holy apostolic and metropolitan Church of Compostela, guardian of the seal of the Altar of the blessed Apostle James, in order that it may provide authentic certificates of visitation to all the faithful and to pilgrims from all over the earth who come with devout affection or for the sake of a vow to the shrine of our Apostle St. James, the patron and protector of Spain, hereby makes known to each and all who shall inspect this present document that [Name]has visited this most sacred temple for the sake of pious devotion. As a faithful witness of these things I confer upon him [or her] the present document, authenticated by the seal of the same Holy Church.

Given at Compostela on the [day] of the month of [month] in the year of the Lord [year].

Deputy Canon for Pilgrims

The simpler certificate of completion in Spanish for those with non-religious motivation reads:

La S.A.M.I. Catedral de Santiago de Compostela le expresa su bienvenida cordial a la Tumba Apostólica de Santiago el Mayor; y desea que el Santo Apóstol le conceda, con abundancia, las gracias de la Peregrinación.

English translation:

The Holy Apostolic Metropolitan Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela expresses its warm welcome to the Tomb of the Apostle St. James the Greater; and wishes that the holy Apostle may grant you, in abundance, the graces of the Pilgrimage.

The Pilgrim's Office gives more than 100,000 compostelas each year to pilgrims from more than 100 different countries.

Pilgrim's Mass

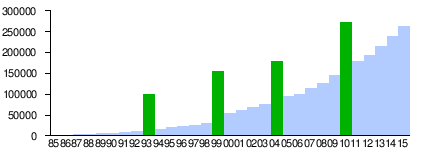

Green bars are holy years |

A Pilgrim's Mass is held in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela each day at 12:00 and 19:30.[24] Pilgrims who received the compostela the day before have their countries of origin and the starting point of their pilgrimage announced at the Mass. The Botafumeiro, one of the largest censers in the world, is operated during certain Solemnities and on every Friday, except Good Friday, at 19:30.[25] Priests administer the Sacrament of Penance, or confession, in many languages. In the Holy Year of 2010 the Pilgrim's Mass was exceptionally held four times a day, at 10:00, 12:00, 18:00, and 19:30, catering for the greater number of pilgrims arriving in the Holy Year.[26]

As tourism

The Xunta de Galicia (Galicia's regional government) promotes the Way as a tourist activity, particularly in Holy Compostelan Years (when 25 July falls on a Sunday). Following the Xunta's considerable investment and hugely successful advertising campaign for the Holy Year of 1993, the number of pilgrims completing the route has been steadily rising. The next Holy Year will occur in 2021, 11 years after the last Holy Year of 2010. More than 272,000 pilgrims made the trip during the course of 2010.

| Year | Pilgrims |

|---|---|

| 2015 | 262,458 |

| 2014 | 237,886 |

| 2013 | 215,880 |

| 2012 | 192,488 |

| 2011 | 179,919 |

| 2010 | 272,7031 |

| 2009 | 145,877 |

| 2008 | 125,141 |

| 2007 | 114,026 |

| 2006 | 100,377 |

| 2005 | 93,924 |

| 2004 | 179,9441 |

| 2003 | 74,614 |

| 2002 | 68,952 |

| 2001 | 61,418 |

| 2000 | 55,004³ |

| 1999 | 154,6131 |

| 1998 | 30,126 |

| 1997 | 25,179 |

| 1996 | 23,218 |

| 1995 | 19,821 |

| 1994 | 15,863 |

| 1993 | 99,4361 |

| 1992 | 9,764 |

| 1991 | 7,274 |

| 1990 | 4,918 |

| 1989 | 5,760² |

| 1988 | 3,501 |

| 1987 | 2,905 |

| 1986 | 1,801 |

| 1985 | 690 |

| 1 Holy Years (Xacobeo/Jacobeo) 2 4th World Youth Day in Santiago de Compostela 3 Santiago named European Capital of Culture Source: The archives of Santiago de Compostela.[27][28][29] | |

In film and television

(Chronological)

- The pilgrimage is central to the plot of the film The Milky Way (1969), directed by surrealist Luis Buñuel. It is intended to critique the Catholic church, as the modern pilgrims encounter various manifestations of Catholic dogma and heresy.

- The Naked Pilgrim (2003) documents the journey of art critic and journalist Brian Sewell to Santiago de Compostela for the UK's Channel Five. Travelling by car along the French route, he visited many towns and cities on the way including Paris, Chartres, Roncesvalles, Burgos, Leon and Frómista. Sewell, a lapsed Catholic, was moved by the stories of other pilgrims and by the sights he saw. The series climaxed with Sewell's emotional response to the Mass at Compostela.

- The Way of St. James was the central feature of the film Saint Jacques... La Mecque (2005) directed by Coline Serreau.

- In The Way (2010), starring Martin Sheen and Emilio Estevez, who also wrote and directed, the principal character (a father played by Sheen) walked the Way of St. James learns that his son has died on the route and takes up the pilgrimage in order to complete it for his son. The film was presented at the Toronto International Film Festival in September 2010,[30][31] and premiered in Santiago in November 2010.

- On his PBS travel Europe television series, Rick Steves covers Northern Spain and the Camino de Santiago in series 6. The cited reference contains information about this episode and resources for the trip, as well as blog posts and user comments.[32]

- In 2013, Simon Reeve presented the "Pilgrimage" series on BBC2, in which he followed various pilgrimage routes across Europe including the Camino de Santiago in episode 2.[33]

- Life in a Walk (2015) follows Yogi Roth and his father, Will, on their trek along the Camino De Santiago.

Selected literature

(Alphabetical by author's surname)

- Anne Carson, "Kinds of Water" (1987). A prose poem that traces the narrator's journey, focusing on the philosophical questions it raises, especially with regards to the nature and desire of the pilgrim. The piece can be found in the anthology of Carson's essays, Plainwater (1995).

- Paulo Coelho, The Pilgrimage (1987)

- Jack Hitt, Off the Road: A Modern-Day Walk Down the Pilgrim’s Route into Spain (1994)

- Hape Kerkeling, I'm Off Then: Losing and Finding Myself on the Camino de Santiago (2009), on his 2001 voyage. It is the best-selling German-language non-fiction book since Gods, Graves and Scholars (1949).

- Hemingway, Ernest, "The Sun Also Rises" (1926). Jake's journey from France to the fiesta of San Fermin is an undertaking of the pilgrimage of Santiago de Compestela.

- David Lodge, Therapy (1995)

- Shirley Maclaine, The Camino: A Journey of the Spirit (2001)

- James Michener, Iberia (1968), contains one chapter about the Camino de Santiago.

- Cees Nooteboom, Roads to Santiago (1996, English edition)

- Conrad Rudolph, Pilgrimage to the End of the World: The Road to Santiago de Compostela (2004)

- Walter Starkie, The Road to Santiago (1957) John Murray, reprinted 2003.

See also

- Camino de Santiago (route descriptions)

- Codex Calixtinus

- Confraternity of Saint James

- Cross of Saint James

- Dominic de la Calzada

- Hajj

- Order of Santiago

- Palatine Ways of St. James

- Via Jacobi

- World Heritage Sites of the Routes of Santiago de Compostela in France

References

- ↑ "Routes of Santiago de Compostela: Camino Francés and Routes of Northern Spain". UNESCO.

- ↑ Starkie, Walter (1965) [1957]. The Road to Santiago: Pilgrims of St. James. University of California Press.

- ↑

Kent, William H. (1913). "Indulgences". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. This entry on indulgences suggests that the evolution of the doctrine came to include pilgrimage to shrines as a trend that developed from the 8th century A.D.: "Among other forms of commutation were pilgrimages to well-known shrines such as that at St. Albans in England or at Compostela in Spain. But the most important place of pilgrimage was Rome. According to Bede (674–735) the visitatio liminum, or visit to the tomb of the Apostles, was even then regarded as a good work of great efficacy (Hist. Eccl., IV, 23). At first the pilgrims came simply to venerate the relics of the Apostles and martyrs; but in course of time their chief purpose was to gain the indulgences granted by the pope and attached especially to the Stations."

Kent, William H. (1913). "Indulgences". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. This entry on indulgences suggests that the evolution of the doctrine came to include pilgrimage to shrines as a trend that developed from the 8th century A.D.: "Among other forms of commutation were pilgrimages to well-known shrines such as that at St. Albans in England or at Compostela in Spain. But the most important place of pilgrimage was Rome. According to Bede (674–735) the visitatio liminum, or visit to the tomb of the Apostles, was even then regarded as a good work of great efficacy (Hist. Eccl., IV, 23). At first the pilgrims came simply to venerate the relics of the Apostles and martyrs; but in course of time their chief purpose was to gain the indulgences granted by the pope and attached especially to the Stations." - ↑ "Holy Years at Santiago de Compostela". Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ↑ "Medieval footpath under the stars of the Milky Way". Telegraph Online.

- ↑ Chadwick, Henry (1976), Priscillian of Avila, Oxford University Press

- ↑ Fletcher, Richard A. (1984), Saint James's Catapult : The Life and Times of Diego Gelmírez of Santiago de Compostela, Oxford University Press

- ↑ Starkie, Walter (1965) [1957]. The Road to Santiago: Pilgrims of St. James. University of California Press. p. 71.

- ↑ "Camino de Santiago en Navarra". Government of Navarre. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ↑ Pilgrim's or Palmer's Staff (fr. bourdon): this was used as a device in a coat of arms as early at least as Edward II's reign, as will be seen. The Staff and the Escallop shell (q.v.) were the badge of the pilgrim, and hence it is but natural it should find its way into the shields of those who had visited the Holy Land. The usual form of representation is figure 1, but in some the hook is wanting, and when this is the case it is scarcely distinguishable from a pastoral staff as borne by some of the monasteries: it is shown in figure 2. While, too, it is represented under different forms, it is blazoned as will be seen also, under different names, e.g. a pilgrim's crutch, a crutch-staff, &c., but there is no reason to suppose that the different names can be correlated with different figures. The crutch, perhaps, should be represented with the transverse piece on the top of the staff (like the letter T) instead of across it. heraldsnet.org

- ↑ "Brief history: The Camino – past, present & future". Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ↑ Davies, Bethan; Cole, Ben (2003). Walking the Camino de Santiago. Pili Pala Press. p. 179. ISBN 0-9731698-0-X.

- ↑ Bignami, Giovanni F. (26 March 2004). "Visions of the Milky Way". Science. 303 (5666): 1979. doi:10.1126/science.1096275. JSTOR 3836327.

- ↑ "Pilgrimages". New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia, retrieved 1 December 2006.

- ↑ "Huellas españolas en Flandes". Turismo de Bélgica. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012.

- ↑ "John Adams autobiography, part 3, Peace, 1779-1780, sheet 10 of 18". Harvard University Press, 1961. August 2007.

- ↑ Henry Adams, The Education of Henry Adams

- ↑ "More Popular Than Ever, Way of St. James Still Offers Enlightenment". Der Spiegel.

- ↑ "The present-day pilgrimage". The Confraternity of Saint James.

- ↑ "Primitive Way-Camino de Santiago Primitivo". Retrieved 2015-12-15.

- ↑ The Confraternity of Saint James. "The Camino Portugués". Retrieved 2016-05-17.

- ↑ "The Compostela". Confraternity of Saint James. Archived from the original on 29 January 2015. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Masses Hours". catedraldesantiago.es. Catedral de Santiago de Compostela. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- ↑ "The Botafumiero". catedraldesantiago.es. Catedral de Santiago de Compostela. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- ↑ "The Holy Year: When Does the Holy Year Take Place?". catedraldesantiago.es. Catedral de Santiago de Compostela. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

It is Holy Year in Compostela when the 25th of July, Commemoration of the Martyrdom of Saint James, falls on a Sunday.

December 8, 2015-November 20, 2016, Pope Francis's Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy, is also a Holy Year. - ↑ "Pilgrims by year according to the office of pilgrims at the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela".

- ↑ "Pilgrims 2006-2009 according to the office of pilgrims at the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela".

- ↑ "Statistics".

- ↑ "The Way (2010)". IMDb. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ↑ "The way official movie site". Theway-themovie.com. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ↑ "Rick Steves travel show, episode: "Northern Spain and the Camino de Santiago"". ricksteves.com. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ↑ "YouTube".

External links

- huropean peace walk http://www.peacewalk.eu/

- Camino de Santiago Community dedicated to help pilgrims plan their trip

- Comeon.ws, detailed and accurate information about The Caminos and Albergues (GPS tracks, POIs, maps)

- Virtual Visit Cathedral Santiago de Compostela

- Camino de Santiago helping you to Santiago

- Camino de Santiago Backpacking Journals Follow hikers as they walk the Way of Saint James

- The Art of medieval Spain, A.D. 500-1200, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Way of St. James (p. 175-183)

- Free Guide for Hikers on the Way of St. James

- Walk the Camino de Santiago de Compostela First hand pilgrim advice for various European St. James pilgrimage walking routes

- App Mi Camino for Android SmartPhones

- Free Android app and maps for navigation to Camino de Santiago for Android SmartPhones

- Camino Pilgrim Free Android app for planning and walking the Camino de Santiago

- Trekopedia - Camino de Santiago Reference database and mobile apps with GPS, accommodations, available services, attractions, communities, points of interest, etc.

Coordinates: 42°27′32″N 5°52′59″W / 42.459°N 5.883°W