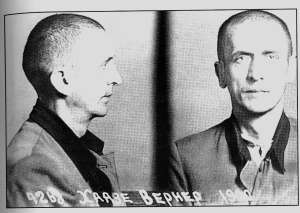

Werner Haase

Werner Haase (2 August 1900 – 30 November 1950) was an SS-Obersturmbannführer (lieutenant colonel), professor of medicine and one of Adolf Hitler's personal physicians.

Biography

Haase was born in Köthen, in Anhalt. He obtained his Doctor's degree in 1924 and then became a surgeon. He joined the Nazi Party in 1933. From 1934, forward, he served on the staff of the surgery clinic of Berlin University.

In 1935, he began serving as Hitler's deputy personal physician. On 1 April 1941, Haase joined the SS. He was promoted to SS-Obersturmbannführer on 16 June 1943. Hitler appears to have had a high opinion of him. The book Hitler's Death: Russia's Last Great Secret from the Files of the KGB, based on documents in the Soviet archives, reproduces a telegram from Hitler sent to Haase on his birthday in 1943, stating: "Accept my heartfelt congratulations on your birthday."[1]

In the last days of the fighting in Berlin in late April 1945, Haase, with Ernst Günther Schenck, worked to save the lives of the many wounded German soldiers and civilians in an emergency casualty station located in the large cellar of the Reich Chancellery. During surgeries, Schenck was aided by Haase. Although Haase had much more surgical experience than Schenck, he was greatly weakened by tuberculosis, and often had to lie down while giving verbal advice to Schenck.[2]

The large Chancellery cellar led a further one-and-a-half meters down to an air-raid shelter known as the Vorbunker.[3] The Vorbunker was connected by a stairway which led down to the Führerbunker.[4] By this time, the Führerbunker had become a de facto Führer Headquarters, and ultimately, the last of Hitler's headquarters.[5]

In addition, Hitler's personal physician Theodor Morell and several others were ordered to leave Berlin by aircraft for the Obersalzberg.[6] When Morell left Berlin on 23 April, he left behind prepared medicine; during the last week of Hitler's life, it was administered by Dr. Haase and by Heinz Linge, Hitler's valet.[7] On 29 April, Hitler expressed doubts about the cyanide capsules he had received through Heinrich Himmler's SS.[8] To verify the capsules' potency, Haase was summoned to the Führerbunker to test one on Hitler's dog Blondi. A cyanide capsule was crushed in the mouth of the dog, which died as a result.[9] Hitler in conversations with Haase during this timeframe, asked the doctor for a recommended method of suicide. Haase instructed Hitler to bite down on a cyanide capsule while shooting himself in the head.[10] He remained in the Führerbunker until Hitler's suicide the following afternoon. Haase then returned to his work at the emergency casualty station. In the seven days they worked together, Schenck and Haas performed some "three hundred and seventy operations".[11] Haase, Helmut Kunz and two nurses, Erna Flegel and Liselotte Chervinska were captured there by Soviet Red Army troops on 2 May.[12]

On 6 May, Haase was one of those taken by the Soviet authorities to identify the bodies of the former Reich Propaganda Minister and (for one day) Reich Chancellor, Joseph Goebbels, his wife Magda Goebbels and their six children. Haase identified Goebbels' body, despite it being partly burned, by the metal brace which Goebbels wore on his deformed right leg.[13]

Haase was made a Soviet prisoner of war. In June 1945 he was charged with being "a personal doctor of the former Reichschancellor of Germany, Hitler, and also treated other leaders of Hitler's government and of the Nazi Party and members of Hitler's SS guard". The sentence is not recorded. Haase, who suffered from tuberculosis, died in captivity in 1950. The place of death is recorded as "Butyr prison hospital".[14] This is probably a reference to the Butyrka prison in Moscow.

Portrayal in the media

Werner Haase has been portrayed by the following actors in film and television productions.

- Morris Perry in the 1981 France/United States television production The Bunker.[15]

- Matthias Habich in the 2004 German film Downfall (Der Untergang).[16]

References

Citations

- ↑ Vinogradov 2005, p. 85.

- ↑ O'Donnell 2001, pp. 148, 150–151.

- ↑ Lehrer 2006, p. 117, 119.

- ↑ Mollo 1988, pp. 28.

- ↑ Beevor 2002, p. 357.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 1999, p. 98.

- ↑ O'Donnell 2001, pp. 37, 125, 317.

- ↑ Kershaw 2008, pp. 951–952.

- ↑ Kershaw 2008, pp. 952.

- ↑ O'Donnell 2001, pp. 322–323.

- ↑ O'Donnell 2001, pp. 147, 148.

- ↑ Vinogradov 2005, p. 62.

- ↑ Vinogradov 2005, p. 84-86.

- ↑ Vinogradov 2005, p. 83.

- ↑ "The Bunker (1981) (TV)". IMDb.com. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- ↑ "Untergang, Der (2004)". IMDb.com. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

Bibliography

- Beevor, Antony (2002). Berlin: The Downfall 1945. London: Viking-Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-670-03041-5.

- Joachimsthaler, Anton (1999) [1995]. The Last Days of Hitler: The Legends, The Evidence, The Truth. Brockhampton Press. ISBN 1-86019-902-X.

- Kershaw, Ian (2008). Hitler: A Biography. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06757-6.

- Lehrer, Steven (2006). The Reich Chancellery and Führerbunker Complex. An Illustrated History of the Seat of the Nazi Regime. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-2393-4.

- Mollo, Andrew (1988). Ramsey, Winston, ed. "The Berlin Führerbunker: The Thirteenth Hole". After the Battle. London: Battle of Britain International (61).

- O'Donnell, James P. (2001) [1978]. The Bunker. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80958-3.

- Vinogradov, V. K. (2005). Hitler's Death: Russia's Last Great Secret from the Files of the KGB. Chaucer Press. ISBN 978-1-904449-13-3.