Whitney Glacier

| Whitney Glacier | |

|---|---|

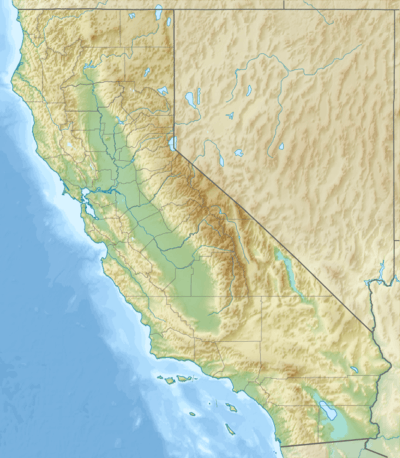

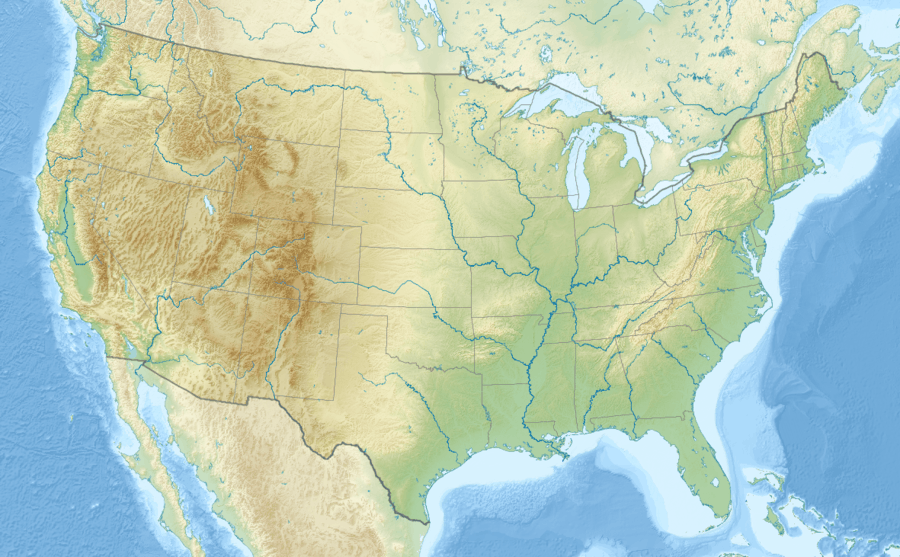

Whitney Glacier  Whitney Glacier Location in California | |

| Type | Mountain glacier |

| Location |

Mount Shasta, Siskiyou County, California, United States |

| Coordinates | 41°24′50″N 122°12′41″W / 41.41389°N 122.21139°WCoordinates: 41°24′50″N 122°12′41″W / 41.41389°N 122.21139°W[1] |

| Area | .5 sq mi (1.3 km2) |

| Length | 2 mi (3.2 km) |

| Thickness | 126 ft (38 m) in 1986 |

| Terminus | Moraine |

| Status | Expanding |

The Whitney Glacier is a glacier situated on Mount Shasta, in the U.S. state of California.[2][3] The Whitney Glacier is the longest glacier and the only valley glacier in California. In area and volume, it ranks second in the state behind the nearby Hotlum Glacier. In 1986, the glacier was measured to be 126 ft (38 m) deep and over three km in length.[4] The glacier starts on Mount Shasta's Misery Hill at 13,700 ft (4,200 m) and then it flows northwestward down to the saddle between Mount Shasta and Shastina.[5] There is a major icefall that occurs there since the ground is very uneven at 11,800 ft (3,600 m).[5] Past the icefall, the glacier flows down the valley between Mount Shasta and Shastina with the terminus at 9,500 to 9,800 ft (2,900 to 3,000 m).[5][6]

Advance

In 2002, scientists made the first detailed survey of Mount Shasta's glaciers in 50 years. They found that seven of the glaciers have grown over the period 1951-2002, with the Hotlum and Wintun Glaciers nearly doubling, the Bolam Glacier increasing by half, and the Whitney and Konwakiton Glaciers growing by a third.[7] The study concluded that though there has been a two to three degree Celsius temperature rise in the region, there has also been a corresponding increase in the amount of snowfall. Increased temperatures have tapped Pacific Ocean moisture, leading to snowfalls that supply the accumulation zone of the glacier with 40 percent more snowfall than is melted in the ablation zone. Over the past 50 years, the glacier has actually expanded 30 percent, which is the opposite of what is being observed in most areas of the world. Researchers have also stated that if the global warming forecast for the upcoming next 100 years are accurate, the increased snowfall will not be enough to offset the increased melting, and the glacier is then likely to retreat.[8][9]

Whitney Glacier, along with the Hubbard Glacier in Alaska, are larger now than in 1890.[10] However, Hubbard Glacier, along with a few other notable glaciers whose termini are at sea level, are calving glaciers.

Glaciologists often point out that glaciers are sensitive indicators of climate. This paradigm should not be applied to calving glaciers. During most of the calving glacier cycle, the slow advances and relatively rapid retreats are not very sensitive to climate. For example, the calving glaciers that are currently growing and advancing in the face of global warming, were retreating throughout the little ice age. Calving glaciers become sensitive to climate only late in the advancing phase, when the mass flux out of the accumulation area approaches the mass lost by melting in the ablation area and losses due to calving can no longer be replaced. No reasonable change in climate will change this imbalance and stop the advances of these few glaciers.[11]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Whitney Glacier". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2012-09-30.

- ↑ "Existing Glaciers of Mount Shasta". College of the Siskiyous. Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ↑ "Glaciers of California". Glaciers of the American West. Glaciers Online. Archived from the original on 2006-09-03. Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ↑ Driedger, Carolyn L.; Kennard, Paul M. (1986). "Ice volumes on Cascade volcanoes; Mount Rainier, Mount Hood, Three Sisters, and Mount Shasta". U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1365. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- 1 2 3 Google Earth elevation for GNIS coordinates.

- ↑ "Whitney Glacier, USGS MOUNT SHASTA (CA) Topo Map". USGS Quad maps. TopoQuest.com. Retrieved 2008-07-05.

- ↑ Harris, Stephen L. (2005). Fire Mountains of the West: The Cascade and Mono Lake Volcanoes (3rd ed.). Mountain Press Publishing Company. p. 109. ISBN 0-87842-511-X.

- ↑ Wong, Kathleen. "California Glaciers". California Wild. California Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on 2006-10-06. Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ↑ Whitney, David (September 4, 2006). "A growing glacier: Mount Shasta bucks global trend, and researchers cite warming phenomena". The Bee. Archived from the original on 2007-01-21. Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ↑ Trabant, D.C.; R.S. March; D.S. Thomas (2003). "Hubbard Glacier, Alaska: Growing and Advancing in Spite of Global Climate Change and the 1986 and 2002 Russell Lake Outburst Floods". U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet FS-001-03. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ↑ Trabant, D.C.; R.S. March; B.F. Molina (2002). "Growing and Advancing Calving Glaciers in Alaska". American Geophysical Union. Retrieved 2007-03-23.

References

- Bill Guyton (2001). Glaciers of California: Modern Glaciers, Ice Age Glaciers, the Origin of the Yosemite Valley, and a Glacier Tour in the Sierra Nevada. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22683-6.