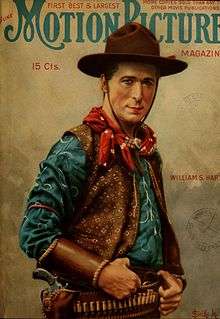

William S. Hart

| William S. Hart | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

William Surrey Hart December 6, 1864 Newburgh, New York, United States |

| Died |

June 23, 1946 (aged 81) Newhall, California, United States |

| Occupation | Actor, screenwriter, director, producer |

| Years active | 1888–1941 |

| Spouse(s) | Winifred Westover (1921–1927) |

| Children | William S. Hart, Jr. (1922–2004) |

William Surrey Hart (December 6, 1864 – June 23, 1946) was an American silent film actor, screenwriter, director and producer.[1] He is remembered as a foremost western star of the silent era who "imbued all of his characters with honor and integrity."[2] During the late 1910s and early 1920s, he was one of the most consistently popular movie stars, frequently ranking high among male actors in popularity contests held by movie fan magazines.[3][4][5]

Biography

Hart was born in Newburgh, New York, to Nicholas Hart (c1834-1895) and Rosanna Hart (c1839–1909). William had 2 brothers, who died very young, and 4 sisters. His father was born in England, and his mother was born in Ireland. He was a distant cousin of the western star Neal Hart.

He began his acting career on stage in his 20s, and in film when he was 49, which coincided with the beginning of film's transition from curiosity to commercial art form.[6] Hart’s stage debut came in 1888 as a member of a company headed by Daniel E. Bandmann. The following year he joined Lawrence Barrett’s company in New York and later spent several seasons with Mlle. Hortense Rhéa’s traveling company.[7] He toured and traveled extensively while trying to make a name for himself as an actor, and for a time directed shows at the Asheville Opera House in North Carolina, around the year 1900. He had some success as a Shakespearean actor on Broadway, working with Margaret Mather and other stars; he appeared in the original 1899 stage production of Ben-Hur. His family had moved to Asheville but, after his youngest sister Lotta died of typhoid fever in 1901, they all left together for Brooklyn until William went back on tour.[8]

Hart went on to become one of the first great stars of the motion picture western. Fascinated by the Old West, he acquired Billy the Kid's "six shooters" and was a friend of legendary lawmen Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson. He entered films in 1914 where, after playing supporting roles in two short films, he achieved stardom as the lead in the feature The Bargain. Hart was particularly interested in making realistic western films. His films are noted for their authentic costumes and props, as well as Hart's acting ability, honed on Shakespearean theater stages in the United States and England.

Beginning in 1915, Hart starred in his own series of two-reel western short subjects for producer Thomas Ince, which were so popular that they were supplanted by a series of feature films. Many of Hart's early films continued to play in theaters, under new titles, for another decade. In 1915 and 1916 exhibitors voted him the biggest money making star in the US.[9] In 1917 Hart accepted a lucrative offer from Adolph Zukor to join Famous Players-Lasky, which merged into Paramount Pictures. In the films Hart began to ride a brown and white pinto he called Fritz. Fritz was the forerunner of later famous movie horses known by their own name, e.g., horses like Tom Mix's Tony, Roy Rogers's Trigger and Clayton Moore's Silver. Hart was now making feature films exclusively, and films like Square Deal Sanderson and The Toll Gate were popular with fans. Hart married young Hollywood actress Winifred Westover. Although their marriage was short-lived, they had one child, William S. Hart, Jr. (1922 – 2004).

By the early 1920s, however, Hart's brand of gritty, rugged westerns with drab costumes and moralistic themes gradually fell out of fashion. The public became attracted by a new kind of movie cowboy, epitomized by Tom Mix, who wore flashier costumes and was faster with the action. Paramount dropped Hart, who then made one last bid for his kind of western. He produced Tumbleweeds (1925) with his own money, arranging to release it independently through United Artists. The film turned out well, with an epic land-rush sequence, but did only fair business at the box office. Hart was angered by United Artists' failure to promote his film properly and sued United Artists. The legal proceedings dragged on for years, and the courts finally ruled in Hart's favor, in 1940.

After Tumbleweeds, Hart retired to his Newhall, California, ranch home, "La Loma de los Vientos,” which was designed by architect Arthur R. Kelly. In 1939 he appeared in his only sound film, a spoken prologue for a reissue of Tumbleweeds. The 75-year-old Hart, filmed on location at his Newhall ranch, reflects on the Old West and recalls his silent-movie days fondly. The speech turned out to be William S. Hart's farewell to the screen. Most prints and video versions of Tumbleweeds circulating today include Hart's speech. Hart died on June 23, 1946, in Newhall, California at the age of 81. He was buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

Dedications

For his contribution to the motion picture industry, William S. Hart has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6363 Hollywood Blvd. In 1975, he was inducted into the Western Performers Hall of Fame at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

As part of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, California, Hart's former home and 260-acre (1.1 km²) ranch in Newhall is now William S. Hart Park. The William S. Hart High School District as well as William S. Hart Senior High School, both located in the Santa Clarita Valley in the northern part of Los Angeles County, were named in his honor. A Santa Clarita baseball field complex is named in his honor.

On November 10, 1962, Hart was honored posthumously in an episode of the short-lived The Roy Rogers and Dale Evans Show, a western variety program on ABC.

Published books

.jpg)

After Hart retired from film making he began writing short stories and book-length manuscripts.[10] His published books are:

- "Pinto Ben and Other Stories" (written with Mary Hart), 1919, Britton Publishing Company

- "Injun and Whitey", 1920, Grossett & Dunlap

- "Injun and Whitey Strike Out For Themselves", 1921, Grossett & Dunlap

- "Injun and Whitey To the Rescue", 1922, Grossett & Dunlap

- "Told Under a White Oak Tree" (credited as by "Bill Hart's Pinto Pony"), 1922, Houghton Mifflin Co.

- "A Lighter of Flames", 1923, Thomas Y. Crowell

- "The Order of Chanta Sutas", 1925, unknown publisher

- "My Life East and West", 1929, Houghton Mifflin Co.

- "Hoofbeats", 1933, Dial Press

- "Law On Horseback and Other Stories", 1935, self-published

- "And All Points West" (written with Mary Hart), 1940, Lacotah Press

Filmography

- Ben-Hur (1907)

- The Bad Buck of Santa Ynez (1914) (extant; Library of Congress)

- The Gringo (1914) (*unconfirmed)

- His Hour of Manhood (1914)

- Jim Cameron's Wife (1914)

- The Bargain (1914)

- Two-Gun Hicks (1914)

- In the Sage Brush Country (1914)

- Grit (1915)

- The Scourge of the Desert (1915)

- Mr. 'Silent' Haskins (1915)

- The Grudge (1915)

- The Sheriff's Streak of Yellow (1915)

- The Roughneck (1915) (?; Library of Congress)

- On the Night Stage (1915)

- The Taking of Luke McVane (1915)

- The Man from Nowhere (1915)

- 'Bad Buck' of Santa Ynez (1915) (extant; Library of Congress)

- The Darkening Trail (1915)

- The Conversion of Frosty Blake (1915)

- Tools of Providence (1915)

- The Ruse (1915) (extant; Library of Congress)

- Cash Parrish's Pal (1915)

- Knight of the Trail (1915)

- Pinto Ben (1915)

- Keno Bates, Liar (1915)

- The Disciple (1915)

- Between Men (1915) (extant; Library of Congress)

- Hell's Hinges (1916) (extant; Library of Congress)

- The Aryan (1916) (extant; Library of Congress)

- The Primal Lure (1916)

- The Apostle of Vengeance (1916)

- The Captive God (1916)

- The Patriot (1916)

- The Dawn Maker (1916)

- The Return of Draw Egan (1916) (extant;DVD)

- The Devil's Double (1916)

- All Star Liberty Loan Drive Special for War Effort (1917)

- Truthful Tulliver (1917)

- The Gun Fighter (1917)

- The Desert Man (1917)

- The Square Deal Man (1917)

- Wolf Lowry (1917)

- The Cold Deck (1917)

- The Silent Man (1917)

- The Narrow Trail (1917)

- Wolves of the Rail (1918)

- The Lion of the Hills (1918)

- Staking His Life (1918)

- 'Blue Blazes' Rawden (1918)

- The Tiger Man (1918)

- Selfish Yates (1918)

- Shark Monroe (1918)

- Riddle Gawne (1918)

- The Border Wireless (1918)

- Branding Broadway (1918)

- Breed of Men (1919)

- The Poppy Girl's Husband (1919)

- The Money Corral (1919)

- Square Deal Sanderson (1919)

- Wagon Tracks (1919) (extant; Library of Congress)

- John Petticoats (1919) (extant; Library of Congress)

- The Toll Gate (1920) (extant; Library of Congress)

- Sand! (1920) (extant, DVD)

- The Cradle of Courage (1920)

- The Testing Block (1920)

- O'Malley of the Mounted (1921)

- The Whistle (1921) (extant; Library of Congress)

- Three Word Brand (1921)

- White Oak (1921) (extant; Library of Congress)

- Travelin' On (1922) (extant; Library of Congress)

- Wild Bill Hickok (1923)

- Singer Jim McKee (1924) (extant; Library of Congress)

- Tumbleweeds (1925) (extant; Library of Congress, others)

- Show People (1928) (*cameo at studio luncheon)

- Tumbleweeds (1940/rerelease) (*filmed talkie prologue to accompany 1925 silent)

The Dawn-Maker (1916)

The Dawn-Maker (1916) The Return of Draw Egan (1916)

The Return of Draw Egan (1916) The Square Deal Man (1917)

The Square Deal Man (1917) The Money Corral (1919)

The Money Corral (1919) The Whistle (1921)

The Whistle (1921) White Oak (1921)

White Oak (1921)

William S. Hart Ranch and Museum

When Hart passed away, he bequeathed his home to Los Angeles County so that it could be converted into a park and museum.[11] His former home in Newhall, Santa Clarita, California has become a satellite of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County and remains free and open to the public to this day.[12] The home is a Spanish Colonial Revival style mansion and contains many of the movie star's possessions including Native American artifacts and works by artists Charles Russell, James Montgomery Flagg, and Joe de Yong.[13] The Museum is an important part of Hart's legacy as he said before he died: "When I was making pictures, the people gave me their nickels, dimes, and quarters. When I am gone, I want them to have my home."[14] The surrounding 265-acre William S. Hart Park includes the mansion, trails, an animal area with farm animals, bison, and a picnic area.[15]

References

- ↑ Obituary Variety, June 26, 1946, page 62.

- ↑ Los Angeles Times

- ↑ "Popularity Contest Closes". Motion Picture Magazine. Chicago: Brewster Publications. December 1920. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- ↑ "The Motion Picture Hall of Fame". Motion Picture Magazine. Chicago: Brewster Publications. July 1918. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- ↑ "The Greatest of Popularity Contests". Motion Picture Classic. Chicago: Brewster Publications. June 1920. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- ↑ William S. Hart Ranch and Museum

- ↑ Davis, Ronald L., 2003. William S. Hart: Projecting the American West - pp. 28-32 Retrieved March 2, 2014

- ↑ Google Books

- ↑ "SHOOTIN FAME.". The Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 – 1954). Hobart, Tas.: National Library of Australia. August 27, 1942. p. 6. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- ↑ Ronald L. Davis, William S. Hart: Projecting the American West, University of Oklahoma Press, 2003

- ↑ http://www.hartmuseum.org/more.html

- ↑ http://www.hartmuseum.org/tours.html

- ↑ http://www.hartmuseum.org/tours.html

- ↑ http://www.hartmuseum.org/more.html

- ↑ "Animals at Hart Park". Friends of Hart Park and Museum. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

Further reading

- William Surrey Hart, My Life East and West, New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1929.

- David W. Menefee, The First Male Stars: Men of the Silent Era, Albany: Bear Manor Media, 2007.

- Jeanine Basinger, Silent Stars, 1999 (ISBN 0-8195-6451-6). (chapter on William S. Hart and Tom Mix)

- Ronald L. Davis, William S. Hart: Projecting the American West, University of Oklahoma Press, 2003.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William S. Hart. |

- William S. Hart at the Internet Movie Database

- William S. Hart at the Internet Broadway Database

- In Loving Memory Of William S. Hart

- William S. Hart Ranch and Museum

- "William S. Hart History". Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society. Retrieved July 4, 2004. (Photos & text)

- William S. Hart Photos and History

- Ron Schuler's Parlour Tricks: The Good Badman

- The Haunted Hart Ghost Site

- William S. Hart Union High School District, Santa Clarita Valley, California

- William S. Hart High School, Newhall, California

- Photographs of William S. Hart

- William S. Hart at Find a Grave

- Works by William S. Hart at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about William S. Hart at Internet Archive

- Works by William S. Hart at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)