Women in the Enlightenment

.jpg)

Although the role of women in the Enlightenment has long been debated, there are still constants that many agree on. Salons were new for the time with women socializing and discussing enlightenment ideas, furthering their roles in society and creating stepping stones for future progress. [1]

Salons and salonnieres

Dena Goodman describes women in the salons of France as a very small number of elite women who were concerned with their own education and promoting the philosophies of the Enlightenment. Their purpose, Goodman says, was to "self-satisfy the educational needs of the women who started them." [2] These women would host a salon either in their own home or in a hotel dining room dedicated to the salon's function. The salons developed from a late set meal where discourse was to take place afterwards to a meal early in the afternoon that would last until late at night. During the meal, the focus would be the discourse between patrons rather than the dining.[3] There was an hierarchical social structure in the salons, and the social rank of French society was upheld but under different rules of conversation. The "conversation was meant to replicate the formality of correspondence to limit conflict and misunderstanding between people of different social ranks and orders."[4] This allowed the common person to interact with the nobility. Through these salons, many people were able to make contacts and possibly move up the social ladder due to their fashionable opinions. Within the hierarchy of the salons, women assumed a role of governance. "As governors, rather than judges, salonierres provided the ground for philosopher's serious work by shaping and controlling the discourse to which men of letters were dedicated and which constituted their project of Enlightenment. In so doing, they transformed the salon from a leisure institution of the nobility to an institution of Enlightenment."[5] Women were able to take this position within the salons because of their gentle, polite, civil nature. Goodman uses the example of the salonierre Suzanne Necker to support her claim that these salons influenced politics, as Necker was married to Louis XVI's financial minister. The assumption is that the salon's topics might therefore have had a bearing on official government policy.[6] The salons were a forum in which elite, well-educated women might continue their learning in a place of civil conversation while governing the political discourse and a place where people of all social orders could interact.

Antoine Lilti offers a differing opinion. While acknowledging the visible hierarchy of the salon, Lilti maintains that "[t]he politeness and congeniality of these aristocrats maintained a fiction of equality that never dissolved differences in status but nonetheless made them bearable." [7] The salons allowed people of varying social classes to converse but never as equals.

Lilti describes two roles for women in the salons, the first being that they took the role of "protectorate."

"The women of the salons played a role not unlike the one traditionally played by women in court society: offering protection, acting on behalf of such or such a person, mobilizing ministers or courtesans. Whether it be in averting the wrath of censors, helping an intrepid author out of the Bastille, securing an audience or a pension, or jockeying for a place in the French Academy, membership in high society and the support of female protectors was indispensable."[8]

The second reason women were involved in the salons was because the salons were based on high society's mixed gender sociability. "The women of the salons ensured the 'decency of the household', enlivened conversation, and served as the guarantors of politeness.'"[9] A woman's presence ensured civilized conversation, not as "governors", but as a discrete way of inducing men to control their conduct. Lilti also maintains that the salons were not used as a way for women to further their education, but as a gathering for social events involving both men and women "in which hostesses welcomed into their homes both male and female socialites, as well as writers, as part of a mixed-gendered sociability dedicated to elite forms of entertainment: dining together, conversation, theatre, music, games, belles-lettres."[8] There was no emphasis on serious intellectual discussion; it was merely a form of entertainment that emphasized the hierarchy of social ranks.

Coffeehouses and debating societies

Brian Cowan has described a coffee house as a place where English virtuosi would gather to converse with others who wanted to increase their knowledge in a civilized setting. "The peculiarly 'virtuosic' emphases on civility, curiosity, cosmopolitanism, and learned discourse made the coffeehouse such a distinctive space in the social world of early modern London." [10] People of all levels of knowledge gathered to share information, and what a person learned depended on their own personal interest.

"The coffeehouse was a place for like-minded scholars to congregate, to read, as well as to learn from and to debate with each other, but it was emphatically not a university institution, and the discourse there was of a far different order than any university tutorial."[11]

These informal practices of education were often condemned. Some educated men commented that "the coffeehouse was an inappropriate venue for the learned discourse that was common currency to all virtuosity."[12] Cowan's version of the coffeehouse is as a completely male-dominated institution.

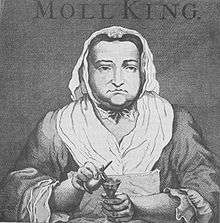

Helen Berry describes another kind of coffee house, one in which women were quite involved. Moll King, for example, not only ran her own coffeehouse but in doing so degraded the virtuosic male-dominated coffee house image. Moll King's "familiarity with urban street life is suggestive of independence and a wild, untamable nature, as well as denoting the more obvious implication of sexual disrepute."[13] When Moll married Thomas King, they opened a small coffeehouse which kept late hours and catered to a clientele very different from the virtuosi.

"Lectures in natural philosophy could be heard at Man's near Charing Cross or Garraway's in Exchange Alley, while the Grecian coffeehouse in the Stand was closely associated with the Royal Society. Moll's was clearly one of the seedier coffeehouses, yet it was popular and attracted fashionable men-about-town."[14]

Moll King's coffeehouse shows that Enlightenment women were not always simply the timid sex, governors of polite conversation, or protectorates of aspiring artists.

Possibly politeness itself, in the Enlightenment context, was not just a uniformly observed set of rules or an attribute which all were striving to attain, but a potentially repressive social force that eighteenth-century men and women, given the opportunity, took peculiar pleasure in transgressing.[15]

Also in England around the time of the coffee houses were debating societies. Donna Andrew depicts these debating societies as a gathering for "the appeal and purposes of meetings that combined instruction with entertainment, gentility with mass audiences, affairs of state with affairs of the heart."[16] Debating societies would rent a hall, charge an admission, and allow the public to discuss many topics in the public sphere. What separated them from other institutions was that they specifically invited women to partake in their discussions. "They (women) were explicitly invited not only to attend, but to take part in debate." [17] Unlike the salons, women were there to participate as equals, not as governors or protectors. Without this restraining governance, there was even violence during some debates.

Even the societies themselves agreed that their proceedings 'might be better regulated.' The president of the Westminster, for example, lamented the presence of 'men of a restless, factious spirit [who] sow dissension in the minds of otherwise peaceable subjects.[16]

Debating societies were initially male-dominated but developed into mixed-gender organizations and also women-only events. At the end of 1780, there were four known women-only debating societies - La Belle Assemblee, the Female Parliament, the Carlisle House Debates for Ladies only, and the Female Congress.[18] The topics often dealt with questions of male and female relations, marriage, courtship, and whether women should be allowed to partake in the political culture. Though women had begun to be asked to partake in the debating societies, there were stipulations as to which societies they could be a part of and when they were permitted to attend. The main stipulation was the non-availability of alcohol. "['t]is remarkable that debating societies which admit ladies, allow no liquor; and those who allow liquor, admit no ladies."[19] Although women did both attend and partake in the debating societies, there was much opposition to this movement at the time. One writer, INDIGNUS, was strongly against the participation of women in debating societies.

Were it really a Fact that these female Orators were any Thing more than The hired Reciters of a studied Lesson, It would be very little to their Honor… But the Truth is….Their lessons are all composed for them; so that they have no more to do with the Arguments they utter, than my Pen has with the Characters I force it to trace.[20]

Women in print

In her book, The Other Enlightenment, Carla Hesse shows that women were much more involved in publishing their writings than previously thought. Hesse explains a major problem that may have led to a decreased number of perceived women writers than before. It comes down to the difference between a woman's being "published" and a woman's "publication." For a woman to be published, she had to have been given the credit for the writing. During most of the Enlightenment, a woman was considered property of her husband; in order for her to publish a work, she had to have the written consent of her husband. When the Old Regime began to fail though, women became more prolific in their publications. The publishers stopped being concerned about which women had consent from their husbands and adopted a completely commercial attitude. The books that were going to sell were going to be published.

The data on women writers suggests that the economic and commercial vision of the Enlightenment and Revolution opened up possibilities for female participation in an absolutely central arena of modern public life that was at odds with the dominant male conception of appropriate relations between the sexes.[21]

After the opening up of the publishing world, it became much easier for women to make a living off of the profession. Writing was a profession that was able to be done anywhere; it could work around any of life's circumstances as long as the person had a pen and paper. "Writing and publishing, as difficult as they are, could be adapted more easily to the contingencies of women's lives (married or unmarried) than any other profession that was as intellectually satisfying and as economically remunerative."[22] Many women who wrote did not write because they needed the money but often wrote for charities. Hesse also shows that the majority of what women were writing at the time defied the gender roles of the day. "Their literary careers had no generic boundaries/Novels were a cherished form of self-expression...but by no means a predominant one."[23]

Another area where women were previously seen as not having participated in a significant way was through Academic Prize Competitions. Historians, such as Pieretti and John Iverson, have promoted the idea that the participation of women in the concours peaked during the time of King Louis XIV and slowly tapered off; others (like Robert Darnton) simply fail to mention them at all. Jeremy Caradonna presents evidence to the contrary, showing that 49 of the over 2000 prize competitions were won by women. This number is a little misleading, however, because many of the women won on more than one occasion. "The abundance of repeat champions brings the total number of female laureates down to 24. Yet numerous women played the circuit without ever ending up in the winner's circle."[24] The idea that women only won because the Prize Competitions were completely anonymous is dispelled by Caradonna as well. "Mlle do Bermann referred to herself as a 'une femme,' and the anonymous concurrente at Châlons began one of her opening sentences with, simply, 'comme je suis fille…'"[25] The shift of the structure of the questions also showed that women were being more heavily encouraged to partake in the Prize Competitions. The questions moved from being related to things it was believed only men would be interested in to questions involving women's rights. The Academy of Besançon even asked a question regarding the education of the woman. After receiving many entries during the two years the competition was open, one of the members of the Academy released a pamphlet chastising misogynist opinions.

The Academy sternly rebuked the contestants for having suggested, audaciously, that women were 'physically incapable,' 'domestic animals,' bred so as to make their spouses 'happy.' [26]

Though there were many women who participated in the Prize Competitions, it does not mean that they were published. Only winning a prize competition ensured publication.

References

- ↑ See Hannah Barker, Elaine Chalus, eds. Gender in Eighteenth-Century England: Roles, Representation and Responsibilities. London: Longman, 1997

- ↑ Goodman, Dena. The Republic of Letters, Cornell Publishers 1994 p.77

- ↑ Goodman, Dena. The Republic of Letters, Cornell Publishers 1994 p.91

- ↑ Goodman, Dena. The Republic of Letters, Cornell Publishers 1994 p.97

- ↑ Goodman, Dena. The Republic of Letters, Cornell Publishers 1994 p.53

- ↑ Goodman, Dena. The Republic of Letters, Cornell Publishers 1994 p.100

- ↑ Lilti, Antoine. Sociability and Mondanite: Men of Letters in the Parisian Salons of the Eighteenth Century, Fayard 2005 p.5

- 1 2 Lilti, Antoine. Sociability and Mondanite:Men of Letters in the Parisian Salons of the Eighteenth Century, Fayard 2005 p.7

- ↑ Lilti, Antoine. Sociability and Mondanite:Men of Letters in the Parisian Salons of the Eighteenth Century, Fayard 2005 p.17

- ↑ Cowan, Brian. The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffee Houses, New Haven: Yale University Press 2005. p.89

- ↑ Cowan, Brian. The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffee Houses, New Haven: Yale University Press 2005. p.91

- ↑ Cowan, Brian. The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffee Houses, New Haven: Yale University Press 2005. p.111

- ↑ Berry, Helen. Rethinking Politeness in Eighteenth Century England:Moll King's Coffee House and the Significance of "Flash Talk", Royal Historical Society 2001. p.69

- ↑ Berry, Helen. Rethinking Politeness in Eighteenth Century England:Moll King's Coffee House and the Significance of "Flash Talk", Royal Historical Society 2001. p.72

- ↑ Berry, Helen. Rethinking Politeness in Eighteenth Century England:Moll King's Coffee House and the Significance of "Flash Talk", Royal Historical Society 2001. p.81

- 1 2 Andrews, Donna. Popular Culture and Public Debate: London 1780 The Historical Journal 1996. p.405

- ↑ Andrews, Donna. Popular Culture and Public Debate: London 1780 The Historical Journal 1996. p.410

- ↑ Andrews, Donna. Popular Culture and Public Debate: London 1780 The Historical Journal 1996. p. 410

- ↑ Andrews, Donna. Popular Culture and Public Debate: London 1780 The Historical Journal 1996. p.409

- ↑ Andrews, Donna. Popular Culture and Public Debate: London 1780 The Historical Journal 1996. p.420

- ↑ Hesse, Carla. The Other Enlightenment: How French Women Became Modern Princeton University Press 2001. p.42

- ↑ Hesse, Carla. The Other Enlightenment: How French Women Became Modern Princeton University Press 2001. p.45

- ↑ Hesse, Carla. The Other Enlightenment: How French Women Became Modern Princeton University Press 2001. p.53

- ↑ Caradonna, Jeremy. Dissertation p.192

- ↑ Caradonna, Jeremy. Dissertation p.199

- ↑ Caradonna, Jeremy. Dissertation p.202