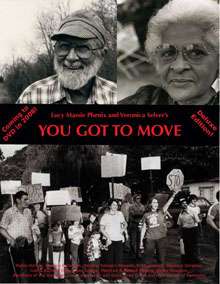

You Got to Move

| You Got to Move | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by |

Lucy Massie Phenix Veronica Selver |

| Produced by | Cumberland Mountain Educational Cooperative |

| Cinematography |

Alan Dater Roger Phenix Gary Steele |

| Edited by | Lucy Massie Phenix |

| Distributed by | Milliarum Zero |

Release dates | 1985 |

Running time | 87 minutes |

| Country | United States of America |

| Language | English |

You Got to Move is a documentary by Lucie Massie Phenix and Veronica Selver that follows people from communities in the Southern United States in their various processes of becoming involved in social change. The film’s centerpiece is the Highlander Folk School (now known as Highlander Research and Education Center), a 75-year-old center for education and social action that was somehow involved in each of the lives chronicled in the documentary.

You Got to Move features folk, country and gospel music from the Southern United States and in fact takes its name from an old spiritual.

Featured People in You Got to Move:

Bernice Robinson A black beautician who became the first teacher of a literacy program on Johns Island, off the coast of South Carolina, talks about teaching adults to read and write in order to pass voter registration requirements during the mid-1950s and 1960s throughout the Southern states.

“I will never forget Anna Vastine. She couldn’t read or write and it was the greatest reward when I had all the names up on the board one night, in jungle fashion, you know and I’d asked them could they pick their names out. Mrs. Vastine said, ‘I see my name,’ and she went down the list and she took the ruler from me and she said, ‘That’s Anna, that’s my first name.’ And then she went over on the other side up and down ‘til she found Vastine and said, ‘That’s my name, V-A-S-T-I-N-E ,Vastine.’ And goose pimples just came out all over me, because that woman couldn’t read or write when she came in there. She was 65 years old.”

Bernice Johnson Reagon A college student who participated in challenging the legality of segregated public facilities in her hometown of Albany, Georgia—a student protest that grew into one of the first city-wide mass Demonstrations of the Civil Rights Movement.

“Now I sit back and look at some of the things we did, and I say, ‘What in the world came over us,’ you know? But death had nothing to do with what we were doing. If somebody shot us we would be dead. And when people died, we cried. And we went to funerals. And we went and did the next thing the next day, because it was really beyond life and death. It was really like... Sometimes you know what you’re supposed to be doing, and when you know what you’re supposed to be doing, it’s somebody else’s job to kill you.”

Bill Saunders A former worker in a mattress factory who now runs a community radio station in Charleston, South Carolina, and was involved in creating a hospital workers’ organization at the Medical College Hospital in Charleston, which organized a 100-day-long hospital workers’ strike in 1969.

“It was really an experience for me, because again, I was able to learn that there were whites tha were suffering the same way that blacks were as it relates to economics. Now, not having access to all of the restrooms, not getting into the lunchroom, they didn’t have those problems. But, actually, they weren’t making any money, and that’s where the problem lies.”

Rebecca Simpson Fought to get damage payments for the people in her community in Cranks Creek, Harlan County, Kentucky much of whose property was destroyed by a series of floods related to strip-mining abuses; succeeded in reclaiming much of the mountainous land around Cranks Creek.

“My education was just like a big black spot in my life. I couldn’t go beyond that, I thought. I thought, probably if you try to do thing like I’ve done, you’d need, you know, like a college degree. But if you ain’t got it, you have to go on without it. So I found out you don’t have to be educated to do what you have to do.”

Gail Story and MaryLee Rogers Two housewives from Bumpass Cove in East Tennessee helped organize community action to stop trucks from dumping hazardous chemicals in the garbage dump in their area.

“Oh mercy, five years ago, and now. Well we was jus ordinary housewives. We taught ourself to drive. We didn’t go any place that we didn’t take the kids, which was just to the grocery store and maybe to the Laundromat. We wasn’t involved in anything, not even PTA. We didn’t feel like we could donate anything. We didn’t think there was anything we could do.” — Gail

“First thing we should say: Our mothers taught us to be good mothers and wives— that’s it. That was our role in life, you know. That’s what was taught and that’s what we did five year ago—watch soap operas. Now I don’t even get to watch a soap opera. I never see a soap opera.” — MaryLee

Myles Horton One of the founders of Highlander Folk School, a 50-year-old center for education and social action.

“I think the future is... well, as somebody said one time, ‘it’s out there.’ It’s not only out there, but it’s ready to be changed. It’s malleable, and there’s nothing fixed that you can’t unfix. But to unfix things that appear to be fixed, you have to not only be creative and imaginative, but courageously dedicated to the long haul.”