Battle of Quiberon Bay

| Battle of Quiberon Bay | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Seven Years' War | |||||||

The Battle of Quiberon Bay, Nicholas Pocock, 1812. National Maritime Museum | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

24 ships of the line 5 frigates |

21 ships of the line 6 frigates | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

2 ships of the line wrecked, 400 killed. |

6 ships of the line destroyed, 1 ship of the line captured, 2,500 killed/drowned. | ||||||

The Battle of Quiberon Bay (known as Bataille des Cardinaux in French), was a decisive naval engagement fought on 20 November 1759 during the Seven Years' War between the Royal Navy and the French Navy. It was fought in Quiberon Bay, off the coast of France near St. Nazaire. The battle was the culmination of British efforts to eliminate French naval superiority, which could have given the French the ability to carry out their planned invasion of Great Britain. A British fleet of 24 ships of the line under Sir Edward Hawke tracked down and engaged a French fleet of 21 ships of the line under Marshal de Conflans. After hard fighting, the British fleet sank or ran aground six ships, captured one and scattered the rest, giving the Royal Navy one of its greatest victories, and ending the threat of French invasion for good.

The battle signalled the rise of the Royal Navy in becoming the world's foremost naval power, and, for the British, was part of the Annus Mirabilis of 1759.

Background

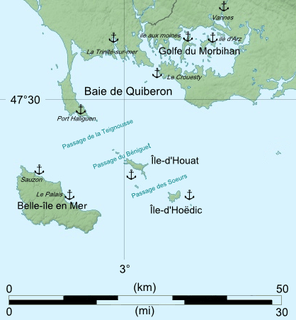

During 1759, the British, under Hawke, maintained a close blockade on the French coast in the vicinity of Brest. In that year the French had made plans to invade England and Scotland, and had accumulated transports and troops around the Loire estuary. The defeat of the Mediterranean fleet at the Battle of Lagos in August made the invasion plans impossible, but Choiseul still contemplated a plan for Scotland, and so the fleet was ordered to escape the blockade and collect the transports assembled in the Gulf of Morbihan.

During the first week of November a westerly gale came up and, after three days, the ships of Hawke's blockade were forced to run for Torbay on the south coast of England. Robert Duff was left behind in Quiberon Bay, with a squadron of five 'fifties' (ships of the line with 50 cannons) and nine frigates to keep an eye on the transports.[2] In the meantime, a small squadron from the West Indies joined Conflans in Brest and, when an easterly wind came on the 14th, Conflans slipped out. He was sighted by HMS Actaeon which had remained on station off Brest despite the storms but which failed to rendezvous with Hawke, by HMS Juno & Swallow which tried to warn Duff but were apparently chased off by the French, and by the victualler Love and Unity returning from Quiberon, which sighted the French fleet at 2pm on the 15th, 70 miles west of Belle-Isle.[3] She met Hawke the next day and he sailed hard for Quiberon into a SSE gale. Meanwhile, HMS Vengeance had arrived in Quiberon Bay the night before to warn Duff and he had put his squadron to sea in the teeth of a WNW gale.[4]

Battle

Having struggled with unfavourable winds, Conflans had slowed down on the night of the 19th in order to arrive at Quiberon at dawn. 20 miles off Belleisle he sighted seven of Duff's squadron.[4] Once he realised that this was not the main British fleet, he gave chase. Duff split his ships to the north and south, with the French van and centre in pursuit, whilst the rearguard held off to windward to watch some strange sails appearing from the west.[5] The French broke off the pursuit but were still scattered as Hawke's fleet came into sight.[5] HMS Magnanime sighted the French at 8.30[4] and Hawke gave the signal for line abreast.[5]

Conflans was faced with a choice, to fight in his current disadvantageous position in high seas and a "very violent" WNW wind, or take up a defensive position in Quiberon Bay and dare Hawke to come into the labyrinth of shoals and reefs.[6] About 9am Hawke gave the signal for general chase along with a new signal for the first 7 ships to form a line ahead and, in spite of the weather and the dangerous waters, set full sail.[7] By 2.30 Conflans rounded Les Cardinaux, the rocks at the end of the Quiberon peninsula that give the battle its name in French. The first shots were heard as he did so, although Sir John Bentley in Warspite claimed that they were fired without his orders.[8] However the British were starting to overtake the rear of the French fleet even as their van and centre made it to the safety of the bay.

Just before 4pm the battered Formidable surrendered to the Resolution, just as Hawke himself rounded The Cardinals.[9] Meanwhile, Thésée lost her duel with HMS Torbay and foundered, Superbe capsized, and the badly damaged Héros struck her flag to Viscount Howe[9] before running aground on the Four Shoal during the night.

Meanwhile, the wind shifted to the NW, further confusing Conflans' half-formed line as they tangled together in the face of Hawke's daring pursuit. Conflans tried unsuccessfully to resolve the muddle, but in the end decided to put to sea again. His flagship, Soleil Royal, headed for the entrance to the bay just as Hawke was coming in on Royal George. Hawke saw an opportunity to rake Soleil Royal, but Intrépide interposed herself and took the fire.[10] Meanwhile, Soleil Royal had fallen to leeward and was forced to run back and anchor off Croisic, away from the rest of the French fleet. By now it was about 5pm and darkness had fallen, so Hawke made the signal to anchor.[10]

During the night eight French ships managed to do what Soleil Royal had failed to do, to navigate through the shoals to the safety of the open sea, and escape to Rochefort.[11] Seven ships and the frigates were in the Villaine estuary (just off the map above, to the east), but Hawke dared not attack them in the stormy weather.[11] The French jettisoned their guns and gear and used the rising tide and northwesterly wind to escape over the sandbar at the bottom of the Villaine river.[11] One of these ships was wrecked, and the remaining six were trapped throughout 1760 by a blockading British squadron and only later managed to break out and reach Brest in 1761/1762.[12] The badly damaged Juste was lost as she made for the Loire, 150 of her crew surviving the ordeal,[13] and Resolution grounded on the Four Shoal during the night.

Richard Wright 1760

Soleil Royal tried to escape to the safety of the batteries at Croisic, but Essex pursued her with the result that both were wrecked on the Four Shoal beside Heros.[11] On the 22nd the gale moderated, and three of Duff's ships were sent to destroy the beached ships. Conflans set fire to Soleil Royal while the British burnt Heros,[11] as seen in the right of Richard Wright's painting. Hawke tried to attack the ships in the Villaine with fireboats, but to no effect.[10]

Aftermath

The power of the French fleet was broken, and would not recover before the war was over; in the words of Alfred Thayer Mahan (The Influence of Sea Power upon History), "The battle of 20 November 1759 was the Trafalgar of this war, and [...] the English fleets were now free to act against the colonies of France, and later of Spain, on a grander scale than ever before". For instance, the French could not follow up their victory at the land Battle of Sainte-Foy in what is now Canada in 1760 for want of reinforcements and supplies from France, and so Quiberon Bay may be regarded as the battle that determined the fate of New France and hence Canada. Hawke's commission was extended and followed by a peerage (allowing him and his heirs to speak in the House of Lords) in 1776.

France experienced a credit crunch as financiers recognised that Britain could now strike at will against French trade.[14] The French government was forced to default on its debt.[14]

Order of battle

France

| Name | Guns | Commander | Men | Notes |

| First Division | ||||

| Soleil Royal | 80 | Paul Osée Bidé de Chézac | 950 | Flagship of Marquis de Conflans – Aground and burnt |

| Orient | 80 | Alain Nogérée de la Filière | 750 | Flagship of Chevalier de Guébridant Budes – Escaped to Rochefort |

| Glorieux | 74 | René Villars de la Brosse-Raquin | 650 | Escaped to the Vilaine, blockaded there until April, 1762[12] |

| Robuste | 74 | Fragnier de Vienne | 650 | Escaped to the Vilaine, blockaded there until 1761, returned to Brest in January, 1762[12] |

| Dauphin Royal | 70 | André d’Urtubie | 630 | Escaped to Rochefort |

| Dragon | 64 | Louis-Charles Le Vassor de La Touche | 450 | Escaped to the Vilaine, blockaded there until January, 1761[12] |

| Solitaire | 64 | Louis-Vincent de Langle | 450 | Escaped to Rochefort |

| Second Division | ||||

| Tonnant | 80 | Antoine de Marges de Saint-Victoret | 800 | Flagship of Chevalier de Beauffremont – Escaped to Rochefort |

| Intrépide | 74 | Charles Le Mercerel de Chasteloger | 650 | Escaped to Rochefort |

| Thésée | 74 | Guy François de Kersaint | 650 | Foundered |

| Superbe | 70 | Jean-Pierre-René-Séraphin du Tertre de Montalais | 630 | Sunk by Royal George |

| Northumberland | 64 | Belingant de Kerbabut | 450 | Escaped to Rochefort |

| Éveillé | 64 | Pierre-Bernardin Thierry de La Prévalaye | 450 | Escaped to the Vilaine, blockaded there until 1761, returned to Brest in January, 1762[12] |

| Brillant | 64 | Louis-Jean de Kerémar | 450 | Escaped to the Vilaine, blockaded there until January, 1761[12] |

| Third Division | ||||

| Formidable | 80 | Louis de Saint-André du Verger | 800 | Flagship of De Saint André du Vergé – Taken by Resolution |

| Magnifique | 74 | Bigot de Morogues | 650 | Escaped to Rochefort |

| Héros | 74 | Vicomte de Sanzay | 650 | Surrendered, but ran aground next day during heavy weather, burnt |

| Juste | 70 | François de Saint-Allouarn | 630 | Wrecked in the Loire |

| Inflexible | 64 | Tancrede | 540 | Lost at the entrance to the Vilaine |

| Sphinx | 64 | Goyon | 450 | Escaped to the Vilaine, blockaded there until April, 1762[12] |

| Bizarre | 64 | Prince de Montbazon | 450 | Escaped to Rochefort |

| Frigates and corvettes | ||||

| Hébé | 40 | 300 | Returned to Brest | |

| Aigrette | 36 | Escaped to the Vilaine | ||

| Vestale | 34 | 254 | Escaped to the Vilaine | |

| Calypso | 16 | Paul Alexandre du Bois-Berthelot | Escaped to the Vilaine | |

| Prince Noir | 6 | Pierre-Joseph Kergariou de Roscouet | Escaped to the Vilaine | |

| Other | ||||

| Vengeance | ? | |||

Britain

| Name | Guns | Commander | Men | Notes |

| Royal George | 100 | Captain John Campbell | 880 | Flagship of Sir Edward Hawke |

| Union | 90 | Captain Thomas Evans | 770 | Flagship of Sir Charles Hardy |

| Duke | 80 | Samuel Graves | 800 | |

| Namur | 90 | Matthew Buckle | 780 | |

| Mars | 74 | Commodore James Young | 600 | |

| Warspite | 74 | Sir John Bentley | 600 | |

| Hercules | 74 | William Fortescue | 600 | |

| Torbay | 74 | Augustus Keppel | 600 | |

| Magnanime | 74 | Viscount Howe | 600 | |

| Resolution | 74 | Henry Speke | 600 | Wrecked on Le Four shoal |

| Hero | 74 | George Edgcumbe | 600 | |

| Swiftsure | 70 | Sir Thomas Stanhope | 520 | |

| Dorsetshire | 70 | Peter Denis | 520 | |

| Burford | 70 | James Gambier | 520 | |

| Chichester | 70 | William Saltren Willet | 520 | |

| Temple | 70 | Washington Shirley | 520 | |

| Essex | 64 | Lucius O'Brien | 480 | Wrecked on Le Four shoal |

| Revenge | 64 | John Storr | 480 | |

| Montague | 60 | Joshua Rowley | 400 | |

| Kingston | 60 | Thomas Shirley | 400 | |

| Intrepid | 60 | Jervis Maplesden | 400 | |

| Dunkirk | 60 | Robert Digby | 420 | |

| Defiance | 60 | Patrick Baird | 420 | |

| Rochester | 50 | Robert Duff | 350 | |

| Portland | 50 | Mariot Arbuthnot | 350 | |

| Falkland | 50 | Francis Samuel Drake | 350 | |

| Chatham | 50 | John Lockhart | 350 | |

| Venus | 36 | Thomas Harrison | 240 | |

| Minerva | 32 | Alexander Hood | 220 | |

| Sapphire | 32 | John Strachan | 220 | |

| Vengeance | 28 | Gamaliel Nightingale | 200 | |

| Coventry | 28 | Francis Burslem | 200 | |

| Maidstone | 28 | Dudley Digges | 200 |

Namesake

HMAS Quiberon was a destroyer named in memory of the battle of Quiberon Bay. She served in the Royal Navy and then the Royal Australian Navy. Quiberon was launched in 1942 and saw operations in World War II. She was decommissioned in 1964.[15]

Notes

- ↑ Syrett (ed.). The Royal Navy in European Waters During the American Revolutionary War. p. 59.

- ↑ Corbett, Julian S. (1907), England In The Seven Years War vol II, Longmans Green, p. 50

- ↑ Corbett pp52-3

- 1 2 3 Corbett p59

- 1 2 3 Corbett p60

- ↑ Corbett p61

- ↑ Corbett pp63-4

- ↑ Corbett p65

- 1 2 Corbett p66

- 1 2 3 Corbett p67

- 1 2 3 4 5 Corbett p68

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 O. Troude, Batailles navales de la France, Volume 1

- ↑ N°3 (printemps 2009) - Le Pouliguen

- 1 2 Corbett p72

- ↑ Cassells, Vic (2000). The Destroyers: their battles and their badges. East Roseville, New South Wales: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7318-0893-2. OCLC 46829686.

Sources and references

- Charnock, John Esq., Biographia Navalis, Vols.5 & 6 (London 1798)

- Clowes, W.L. (ed.). The Royal Navy; A History, from the Earliest Times to the Present, Volume III. (London 1898).

- Jenkins, E.H. A History of the French Navy (London 1973).

- McLynn, Frank. 1759: the year Britain became master of the world (Random House, 2011) pp 354-87.

- Mackay, R.F. Admiral Hawke (Oxford 1965).

- Marcus, G. Quiberon Bay; The Campaign in Home Waters, 1759 (London, 1960).

- Padfield, Peter. Maritime Supremacy & the Opening of the Western Mind: Naval Campaigns that Shaped the Modern World (Overlook Books, 2000).

- Robson, Martin. A History of the Royal Navy: The Seven Years War (IB Tauris, 2015).

- Syrett, David (1998). The Royal Navy in European Waters During the American Revolutionary War. Univ of South Carolina Press. ISBN 9781570032387.

- Tracy, Nicholas. The Battle of Quiberon Bay, 1759: Hawke and the Defeat of the French Invasion. (2010).

- Tunstall, Brian and Tracy, Nicholas (ed.). Naval Warfare in the Age of Sail. The Evolution of Fighting Tactics, 1650-1815 (London, 1990).

- Wheeler, Dennis. "A climatic reconstruction of the Battle of Quiberon Bay, 20 November 1759." Weather 50.7 (1995): 230-239. weather conditions

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Quiberon Bay. |