Battle of Culloden

| Battle of Culloden | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Jacobite rising of 1745 | |||||||

An incident in the rebellion of 1745, by David Morier | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Duke of Cumberland | Charles Edward Stuart | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

8,000 10 guns 6 mortars |

7,000 12 guns | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

240-400 killed[2] 1000 wounded[2] |

Jacobites: 1,500–2,000 killed or wounded[2][3] 154 captured[2] France: 222 captured[2] | ||||||

The Battle of Culloden (Scottish Gaelic: Blàr Chùil Lodair) was the final confrontation of the Jacobite rising of 1745 and part of a religious civil war in Britain. On 16 April 1746, the Jacobite forces of Charles Edward Stuart were decisively defeated by loyalist troops commanded by William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, near Inverness in the Scottish Highlands.

Queen Anne died in 1714, with no living children; she was the last monarch of the House of Stuart. Under the terms of the Act of Settlement 1701, she was succeeded by her second cousin George I of the House of Hanover, who was a descendant of the Stuarts through his maternal grandmother, Elizabeth, a daughter of James VI and I. The Hanoverian victory at Culloden halted the Jacobite intent to overthrow the House of Hanover and restore the House of Stuart to the British throne; Charles Stuart never again tried to challenge Hanoverian power in Great Britain. The conflict was the last pitched battle fought on British soil.[4]

Charles Stuart's Jacobite army consisted largely of Catholics and Episcopalians, mainly Scots but with a small detachment of Englishmen from the Manchester Regiment. The Jacobites were supported and supplied by the Kingdom of France from Irish and Scots units in the French service. A composite battalion of infantry ("Irish Picquets") comprising detachments from each of the regiments of the Irish Brigade plus one squadron of Irish in the French army served at the battle alongside the regiment of Royal Scots (Royal Ecossais) raised the previous year to support the Stuart claim.[5] The British Government (Hanoverian loyalist) forces were mostly Protestants – English, along with a significant number of Scottish Lowlanders and Highlanders, a battalion of Ulstermen and some Hessians from Germany[6] and Austrians.[7] The quick and bloody battle on Culloden Moor was over in less than an hour when after an unsuccessful Highland charge against the government lines, the Jacobites were routed and driven from the field.

Between 1,500 and 2,000 Jacobites were killed or wounded in the brief battle. Government losses were lighter with 50 dead and 259 wounded although recent geophysical studies on the government burial pit suggest the figure for deaths to be nearer 300. The battle and its aftermath continue to arouse strong feelings: the University of Glasgow awarded Cumberland an honorary doctorate, but many modern commentators allege that the aftermath of the battle and subsequent crackdown on Jacobitism were brutal, and earned Cumberland the sobriquet "Butcher". Efforts were subsequently taken to further integrate the comparatively wild Highlands into the Kingdom of Great Britain; civil penalties were introduced to weaken Gaelic culture and attack the Scottish clan system.

Background

.svg.png)

Charles Edward Stuart, known as "Bonnie Prince Charlie" or the "Young Pretender", arrived in Scotland in 1745 to incite a rebellion of Stuart sympathizers against the House of Hanover. He successfully raised forces, mainly of Scottish Highland clansmen, and slipped past the Hanoverian stationed in Scotland and defeated a force of militiamen at the Battle of Prestonpans. The city of Edinburgh was occupied, but the castle held out and most of the Scottish population remained hostile to the rebels; others, while sympathetic, were reluctant to lend overt support to a movement whose chances were unproven. The British government recalled forces from the war with France in Flanders to deal with the rebellion.

After a lengthy wait, Charles persuaded his generals that English Jacobites would stage an uprising in support of his cause. He was convinced that France would launch an invasion of England as well. His army of around 5,000 invaded England on 8 November 1745. They advanced through Carlisle and Manchester to Derby and a position where they appeared to threaten London. It is often alleged that King George II made plans to decamp to Hanover, but there is no evidence for this and the king is on record as stating that he would lead the troops against the rebels himself if they approached London. (George had experience at the head of an army: in 1743 he had led his soldiers to victory at the Battle of Dettingen, becoming the last British monarch to lead troops into battle.[8]) The Jacobites met only token resistance. There was, however, little support from English Jacobites, and the French invasion fleet was still being assembled. The armies of Field Marshal George Wade and of William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, were approaching. In addition to the militia, London was defended by nearly 6,000 infantry, 700 horse and 33 artillery pieces and the Jacobites received (fictitious) reports of a third army closing on them. The Jacobite general, Lord George Murray, and the Council of War insisted on returning to join their growing force in Scotland. On 6 December 1745, they withdrew, with Charles Edward Stuart leaving command to Murray.

On the long march back to Scotland, the Highland Army wore out its boots and demanded all the boots and shoes of the townspeople of Dumfries as well as money and hospitality. The Jacobites reached Glasgow on 25 December. There they reprovisioned, having threatened to sack the city, and were joined by a few thousand additional men. They then defeated the forces of General Henry Hawley at the Battle of Falkirk Muir. The Duke of Cumberland arrived in Edinburgh on 30 January to take over command of the government army from General Hawley. He then marched north along the coast, with the army being supplied by sea. Six weeks were spent at Aberdeen training.

The King's forces continued to pressure Charles. He retired north, losing men and failing to take Stirling Castle or Fort William. But he invested Fort Augustus and Fort George in Inverness-shire in early April. Charles then took command again, and insisted on fighting a defensive action.

Hugh Rose of Kilravock entertained Charles Edward Stuart and the Duke of Cumberland respectively on 14 and 15 April 1746, before the Battle of Culloden. Charles' manners and deportment were described by his host as most engaging. Having walked out with Mr. Rose, before sitting down he watched trees being planted. He remarked, "How happy, Sir, you must feel, to be thus peaceably employed in adorning your mansion, whilst all the country round is in such commotion." Kilravock was a firm supporter of the house of Hanover, but his adherence was not solicited, nor were his preferences alluded to. The next day, the Duke of Cumberland called at the castle gate, and when Kilravock went to receive him, he bluffly observed, "So you had my cousin Charles here yesterday." Kilravock replied, "What am I to do, I am Scots", to which Cumberland replied, "You did perfectly right."

Opposing forces

Jacobite army

The bulk of the Jacobite army was made up of Highlanders and most of its strength was volunteers. These men made up the gentlemen (officers), cavalry and Lowland units, and as such did much of the fighting during the campaign. The clans which supported the Jacobite cause tended to be Roman Catholic and Scottish Episcopalian, while clans which tended to be Presbyterian sided more with the British government.[10] Nearly three-quarters of the Jacobite army was composed of Highland clansmen who were either Roman Catholic or Episcopalian. The Highlanders served in the clan regiments which were recruited largely from the Highlands of Scotland.[10]

One of the fundamental problems with the Jacobite army was the lack of trained officers. The lack of professionalism and training was readily apparent; even the colonels of the Macdonald regiments of Clanranald and Keppoch considered their men to be uncontrollable.[11][note 1] A typical clan regiment was made up of a small minority of gentlemen (tacksmen) who would bear the "clan name", and under them the common soldiers or "clansmen" who bore a mixed bag of names.[13] The clan gentlemen formed the front ranks of the unit and were more heavily armed than their impoverished tenants who made up the bulk of the regiment.[10] Because they served in the front ranks, the gentlemen suffered higher proportional casualties than the common clansman. The gentlemen of the Appin Regiment suffered one quarter of those killed, and one third of those wounded from their regiment.[13] The Jacobites started the campaign poorly armed. At the Battle of Prestonpans, some only had swords, Lochaber axes, pitchforks and scythes. Although popular imagination pictures the common highlander as being equipped with a broadsword, targe and pistol, it was only officers or gentlemen who were equipped in this way.[14] Further illustrating this point, following the conclusion of the battle, Cumberland reported that there were 2,320 firelocks recovered from the battlefield, but only 190 broadswords. From this, it can be determined that of the roughly 1,000 Jacobites killed at Culloden, no more than one fifth carried a sword.[15] As the campaign progressed, the Jacobites improved their equipment considerably. For instance, 1,500–1,600 stack of arms were landed in October. In consequence, by the time of the Battle of Culloden, the Jacobite army was equipped with 0.69 in (17.5 mm) calibre French and Spanish firelocks.[14]

During the latter stage of the campaign, the Jacobites were reinforced with units of French regulars. These units, like Fitzjames' Horse, and the Irish Picquets, were drawn from the Irish Brigade (Irish units in French service). Another unit was the Royal Écossais ("Royal Scots"), which was a Scottish unit in French service.[16] The majority of these troops were Irish born. Lists of prisoners at Marshalsea, Berwick and prison interviews conducted by Captain Eyre show some of these men to be English born, claiming to have been press-ganged or seized as prisoners on British ships. Fitzjames' Horse was the only Jacobite cavalry unit to fight the whole battle on horseback.[16] Around 500 Irish Picquets in the French army fought in the battle, some of whom were thought to have been press-ganged from 6th (Guise's) Foot taken at Fort Augustus. The Royal Écossais also contained deserters, and the commander, Drummond, attempted to raise a second battalion after the unit had arrived in Scotland.[17] The Jacobite artillery has been generally regarded as being ineffective in the battle. Some modern accounts claim that the Jacobite artillery suffered from having cannon with different calibres of shot. In fact, all but one of the Jacobite cannon were 3-pounders.[17]

Government Army

The Kingdom of Great Britain government army at the Battle of Culloden was made up of infantry, cavalry, and artillery. Of the army's 16 infantry battalions present, four were Scottish units and one was Irish.[18] The officers of the infantry were from the upper classes and aristocracy, while the rank and file were made up of poor agricultural workers. On the outbreak of the Jacobite rising, extra incentives were given to lure recruits to fill the ranks of depleted units. For instance, on 6 September 1745, every recruit who joined the Guards before 24 September was given £6, and those who joined in the last days of the month were given £4. Regiments were named after their Colonel. In theory, an infantry regiment would comprise up to ten companies of up to 70 men. They would then be 815 strong, including officers. However, regiments were rarely anywhere near this large, and at the Battle of Culloden, the regiments were not much larger than about 400 men.[19]

The government cavalry arrived in Scotland in January 1746. They were not combat experienced, having spent the preceding years on anti-smuggling duties. A standard cavalryman had a Land Service pistol and a carbine. However, the main weapon used by the British cavalry was a sword with a 35-inch blade.[20]

The Royal Artillery vastly out-performed their Jacobite counterparts during the Battle of Culloden. However, up until this point in the campaign, the government artillery had performed dismally. The main weapon of the artillery was the 3-pounder. This weapon had a range of 500 yards (460 m) and fired two kinds of shot: round iron and canister. The other weapon used was the Coehorn mortar. These had a calibre of 4 2⁄5 inches (11 cm).[21]

Lead up to battle

.png)

On 30 January, the Duke of Cumberland arrived in Scotland to take command of the government forces after the previous failures by Cope and Hawley. Cumberland decided to wait out the winter, and moved his troops northwards to Aberdeen. Around this time, the army was increased by 5,000 Hessian troops. The Hessian force, led by Prince Frederick of Hesse, took up position to the south to cut off any path of retreat for the Jacobites. The weather had improved to such an extent by 8 April that Cumberland again resumed the campaign. The government army reached Cullen on 11 April, where it was joined by six battalions and two cavalry regiments.[22] Days later, the government army approached the River Spey, which was guarded by a Jacobite force of 2,000, made up of the Jacobite cavalry, the Lowland regiments and over half of the army's French regulars. The Jacobites quickly turned and fled, first towards Elgin and then to Nairn. By 14 April, the Jacobites had evacuated Nairn, and Cumberland camped his army at Balblair just west of the town.[23]

The Jacobite forces of about 5,400 left their base at Inverness, leaving most of their supplies, and assembled 5 miles (8 km) to the east near Drummossie,[24] around 12 miles (19 km) before Nairn. Charles Edward Stuart had decided to personally command his forces and took the advice of his adjutant general, Secretary O'Sullivan, who chose to stage a defensive action at Drummossie Moor,[25] a stretch of open moorland enclosed between the walled Culloden[26] enclosures to the North and the walls of Culloden Park to the South.[27] Lord George Murray "did not like the ground" and with other senior officers pointed out the unsuitability of the rough moorland terrain which was highly advantageous to the Duke with the marshy and uneven ground making the famed Highland charge somewhat more difficult while remaining open to Cumberland's powerful artillery. They had argued for a guerrilla campaign, but Charles Edward Stuart refused to change his mind.

Night attack at Nairn

On 15 April, the government army celebrated Cumberland's twenty-fifth birthday by issuing two gallons of brandy to each regiment.[22] At Murray's suggestion, the Jacobites tried that evening to repeat the success of Prestonpans by carrying out a night attack on the government encampment. Murray proposed that they set off at dusk and march to Nairn. Murray planned to have the right wing of the first line attack Cumberland's rear, while Perth with the left wing would attack the government's front. In support of Perth, Charles Edward Stuart would bring up the second line. The Jacobite force however started out well after dark at about 20:00. Murray led the force cross country with the intention of avoiding government outposts. This however led to very slow going in the dark. Murray's one time aide-de-camp, James Chevalier de Johnstone later wrote, "this march across country in a dark night which did not allow us to follow any track, and accompanied with confusion and disorder".[28] By the time the leading troop had reached Culraick, still 2 miles (3.2 km) from where Murray's wing was to cross the River Nairn and encircle the town, there was only one hour left before dawn. After a heated council with other officers, Murray concluded that there was not enough time to mount a surprise attack and that the offensive should be aborted. O'Sullivan went to inform Charles Edward Stuart of the change of plan, but missed him in the dark. Meanwhile, instead of retracing his path back, Murray led his men left, down the Inverness road. In the darkness, while Murray led one-third of the Jacobite forces back to camp, the other two-thirds continued towards their original objective, unaware of the change in plan. One account of that night even records that Perth and Drummond made contact with government troops before realising the rest of the Jacobite force had turned home. Not long after the exhausted Jacobite forces had made it back to Culloden, reports came of the advancing government troops.[28] By then, many Jacobite soldiers had dispersed in search of food, while others were asleep in ditches and outbuildings.

However, military historian Jeremy Black has contended that even though the Jacobite force had become disordered and lost the element of surprise the night attack remained viable, and that if the Jacobites had advanced the conditions would have made government morale vulnerable and disrupted their fire discipline.[29][30]

Battle on Culloden Moor

Early on a rainy 16 April, the well rested Government army struck camp and at about 05:00 set off towards the moorland around Culloden and Drummossie. Jacobite pickets first sighted the Government advance guard at about 08:00, when the advancing army came within 4 miles (6.4 km) of Drummossie. Cumberland's informers alerted him that the Jacobite army was forming up about 1 mile (1.6 km) from Culloden House—upon Culloden Moor.[31][32] At about 11:00 the two armies were within sight of one another with about 2 miles (3.2 km) of open moorland between them.[31] As the Government forces steadily advanced across the moor, the driving rain and sleet blew from the north-east into the faces of the exhausted Jacobite army.

Opening moves

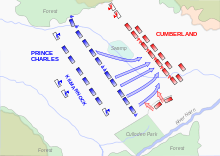

The Jacobite army was originally arrayed between the corners of Culloden and Culwhiniac parks (from left to right): the three Macdonald battalions; a small one of Chisholms; another small one of Macleans and Maclachlans; Lady Mackintosh and Monaltrie's regiments; Lord Lovat's Regiment; Ardsheal's Appin Stewarts; Lochiel's Regiment; and three battalions of the Atholl Brigade. Murray who commanded the right wing, however became aware of the Leanach enclosure that lay ahead of him, a wall that would become an obstacle in the event of a Jacobite advance. Without any consultation he then moved the brigade down the moor and formed into three columns. It seems probable that Murray intended to shift the axis of the Jacobite advance to a more northerly direction, thus having the right wing clear the Leanach enclosure and possibly taking advantage of the downward slope of the moor to the north.[33]

.svg.png)

However, the Duke of Perth seems to have misinterpreted Murray's actions as only a general advance, and the Macdonalds on the far left simply ignored him. The result was the skewing of the Jacobite front line, with the (left wing) Macdonalds still rooted on the Culloden Parks wall and the (right wing) Atholl Brigade halfway down the Culwhiniac Parks wall. In consequence, large gaps immediately appeared in the severely over-stretched Jacobite lines. A shocked Sullivan had no choice but to position the meagre 'second line' to fill the gaps. This second line was (left to right): the Irish Picquets; the Duke of Perth's Regiment; Glenbuchat's; Lord Kilmarnock's Footguards; John Roy Stuart's Regiment; two battalions of Lord Ogilvy's Regiment; the Royal Écossais; two battalions of Lord Lewis Gordon's Regiment. Farther back were cavalry units. On the left were: Lord Strathallan's Horse Bagot's Hussars and possibly Balmerino's Lifeguards. On the right were Lord Elcho's Lifeguards and Fitzjames's Horse. And in the centre was Charles Edward Stuart's tiny escort made up of Fitzjames's Horse and Lifeguards. When Sullivan's redeployment was completed Perth's and Glenbuchat's regiments were standing on the extreme left wing and John Roy Stuart's was standing beside Ardsheal's.[33]

Cumberland brought forward the 13th and 62nd to extend his first and second lines. At the same time, two squadrons of Kingston's Horse were brought forward to cover the right flank. These were then joined by two troops of Cobham's 10th Dragoons. While this was taking place, Hawley began making his way through the Culwhiniac Parks intending to outflank the Jacobite right wing. Anticipating this, the two battalions of Lord Lewis Gordon's regiment had lined the wall. However, since the Government dragoons stayed out of range, and the Jacobites were partly in dead ground they moved back and formed up on a re-entrant at Culchunaig, facing south and covering the army's rear. Once Hawley had led the dragoons through the Parks he deployed them in two lines beneath the Jacobite guarded re-entrant. By this time the Jacobites were guarding the re-entrant from above with four battalions of Lord Lewis Gordon's and Lord Ogilvy's regiments, and the combined squadron of Fitzjames's Horse and Elcho's Lifeguards. Unable to see behind the Jacobites above him, Hawley had his men stand and face the enemy.[33]

Over the next twenty minutes, Cumberland's superior artillery battered the Jacobite lines, while Charles, moved for safety out of sight of his own forces, waited for the Government forces to move. Inexplicably, he left his forces arrayed under Government fire for over half an hour. Although the marshy terrain minimized casualties, the morale of the Jacobites began to suffer. Several clan leaders, angry at the lack of action, pressured Charles to issue the order to charge. The Clan Chattan was first of the Jacobite army to receive this order, but an area of boggy ground in front of them forced them to veer right so that they obstructed the following regiments and the attack was pushed towards the wall. The Jacobites advanced on the left flank of the Government troops, but were subjected to volleys of musket fire and the artillery which had switched from roundshot to grapeshot.

Highland charge

Despite this many Jacobites reached the government lines and, for the first time, a battle was decided by a direct clash between charging highlanders and formed redcoats equipped with muskets and socket bayonets. The brunt of the Jacobite impact was taken by just two government regiments—Barrell's 4th Foot and Dejean's 37th Foot. Barrell's regiment lost 17 and suffered 108 wounded, out of a total of 373 officers and men. Dejean's lost 14 and had 68 wounded, with this unit's left wing taking a disproportionately higher number of casualties. Barrell's regiment temporarily lost one of its two colours.[note 2] Major-General Huske, who was in command of the government's second line, quickly organised the counter attack. Huske ordered forward all of Lord Sempill's Fourth Brigade which had a combined total of 1,078 men (Sempill's 25th Foot, Conway's 59th Foot, and Wolfe's 8th Foot). Also sent forward to plug the gap was Bligh's 20th Foot, which took up position between Sempill's 25th and Dejean's 37th. Huske's counter formed a five battalion strong horseshoe-shaped formation which trapped the Jacobite right wing on three sides.[34]

Poor Barrell's regiment were sorely pressed by those desperadoes and outflanked. One stand of their colours was taken; Collonel Riches hand cutt off in their defence ... We marched up to the enemy, and our left, outflanking them, wheeled in upon them; the whole then gave them 5 or 6 fires with vast execution, while their front had nothing left to oppose us, but their pistolls and broadswords; and fire from their center and rear, (as, by this time, they were 20 or 30 deep) was vastly more fatal to themselves, than us.

.svg.png)

Located on the Jacobite extreme left wing were the Macdonald regiments. Popular legend has it that these regiments refused to charge when ordered to do so, due to the perceived insult of being placed on the left wing.[37] Even so, due to the skewing of the Jacobite front lines, the left wing had a further 200 metres (660 ft) of much boggier ground to cover than the right.[note 3] When the Macdonalds charged, their progress was much slower than that of the rest of the Jacobite forces. Standing on the right of these regiments were the much smaller units of Chisholms and the combined unit of Macleans and Maclachlans. Every officer in the Chisholm unit was killed or wounded and Col. Lachlan Maclachlan, who led the combined unit of Macleans and Maclachlans, was gruesomely killed by a cannon shot. As the Macdonalds suffered casualties they began to give way. Immediately Cumberland then pressed the advantage, ordering two troops of Cobham's 10th Dragoons to ride them down. The boggy ground however impeded the cavalry and they turned to engage the Irish Picquets whom Sullivan had brought up in an attempt to stabilise the deteriorating Jacobite left flank.[note 4][40]

Jacobite collapse and rout

With the collapse of the left wing, Murray brought up the Royal Écossais and Kilmarnock's Footguards who were still at this time unengaged. However, by the time they had been brought into position, the Jacobite army was in rout. The Royal Écossais exchanged musket fire with Campbell's 21st and commenced an orderly retreat, moving along the Culwhiniac enclosure in order to shield themselves from artillery fire. Immediately the half battalion of Highland militia commanded by Captain Colin Campbell of Ballimore which had stood inside the enclosure ambushed the Royal Écossais. Hawley had previously left this Highland unit behind the enclosure, with orders to avoid contact with the Jacobites, to limit any chance of a friendly fire incident. In the encounter Campbell of Ballimore was killed along with five of his men. The result was that the Royal Écossais and Kilmarnock's Footguards were forced out into the open moor and were rushed at by three squadrons of Kerr's 11th Dragoons. The fleeing Jacobites must have put up a fight for Kerr's 11th recorded at least 16 horses killed during the entirety of the battle. The Irish picquets bravely covered the Highlanders retreat from the battlefield and prevented a massacre. This action cost half of the 100 casualties suffered in the battle.[41] The Royal Écossais appear to have retired from the field in two wings. One part of the regiment surrendered upon the field after suffering 50 killed or wounded, but their colours were not taken and a large number retired from the field with the Jacobite Lowland regiments.[42]

.svg.png)

This stand by the Royal Écossais may have given Charles Edward Stuart the time to make his escape. At the time when the Macdonald regiments were crumbling and fleeing the field, Stuart seems to have been rallying Perth's and Glenbuchat's regiments when O'Sullivan rode up to Captain Shea who commanded Stuart's bodyguard: "Yu see all is going to pot. Yu can be of no great succor, so before a general deroute wch will soon be, Seize upon the Prince & take him off ...".[42] Shea then led Stuart from the field along with Perth's and Glenbuchat's regiments. From this point on the fleeing Jacobite forces were split into two groups: the Lowland regiments retired in order southwards, making their way to Ruthven Barracks; the Highland regiments however were cut off by the Government cavalry, and forced to retreat down the road to Inverness. The result was that they were a perfect target for the Government dragoons. Major-general Humphrey Bland led the charge against the fleeing Highlanders, giving "Quarter to None but about Fifty French Officers and Soldiers He picked up in his Pursuit".[42]

Conclusion: casualties and prisoners

Jacobite casualties are estimated at 1,500–2,000 killed or wounded.[2][3] Cumberland's official list of prisoners taken includes 154 Jacobites and 222 "French" prisoners (men from the 'foreign units' in the French service). Added to the official list of those apprehended were 172 of the Earl of Cromartie's men, captured after a brief engagement the day before near Littleferry. In striking contrast to the Jacobite losses, the government forces were 50 dead and 259 wounded, although a high proportion of those recorded as wounded are likely to have died of their wounds. For example, only 29 out of 104 wounded from Barrell's 4th Foot survived to claim pensions. All 6 of the artillerymen recorded as wounded died.[2] The only government casualty of high rank was Lord Robert Kerr, the son of William Kerr, 3rd Marquess of Lothian.

Aftermath

Collapse of the Jacobite campaign

As the first of the fleeing Highlanders approached Inverness they were met by a battalion of Frasers led by the Master of Lovat. Tradition states that the Master of Lovat immediately about-turned his men and marched down the road back towards Inverness, with pipes playing and colours flying. There are however varying traditions as to what happened at the bridge which spans the River Ness. One tradition is that the Master of Lovat intended to hold the bridge until he was persuaded against it. Another is that the bridge was seized by a party of Argyll Militia who were involved in a skirmish when blocking the crossing of retreating Jacobites. While it is almost certain there was a skirmish upon the bridge, it has been proposed that the Master of Lovat shrewdly switched sides and turned upon the fleeing Jacobites. Such an act would explain his remarkable rise in fortune in the years that followed.[45]

Following the battle, the Jacobites' Lowland units headed south, towards Corrybrough and made their way to Ruthven Barracks, while their Highland units headed north, towards Inverness and on through to Fort Augustus. There they were joined by Barisdale's Macdonalds and a small battalion of MacGregors.[45] The roughly 1,500 men who assembled at Ruthven Barracks received orders from Charles Edward Stuart to the effect that all was lost and to "shift for himself as best he could".[46] Similar orders must have been received by the Highland units at Fort Augustus. By 18 April the Jacobite army was disbanded. Officers and men of the units in the French service made for Inverness, where they surrendered as prisoners of war on 19 April. The rest of the army broke up, with men heading for home or attempting to escape abroad.[45]

Some ranking Jacobites made their way to Loch nan Uamh, where Charles Edward Stuart had first landed at the outset of the campaign in 1745. Here on 30 April they were met by the two French frigates—the Mars and Bellone. Two days later the French warships were spotted and attacked by the smaller Royal Navy sloops—the Greyhound, Baltimore, and Terror. The result was the last real battle in the campaign. During the six hours in which the ferocious sea-battle raged the Jacobites recovered cargo on the beach which had been landed by the French ships. In all £35,000 of gold was recovered along with supplies.[45] Invigorated by the vast amounts of loot and visible proof that the French had not deserted them, the group of Highland chiefs decided to prolong the campaign. On 8 May, nearby at Murlaggan, Lochiel, Lochgarry, Clanranald and Barisdale all agreed to rendezvous at Invermallie on 18 May. The plan was that there they would be joined by the what remained of Keppoch's men and Cluny Macpherson's regiment (which did not take part in the battle at Culloden). However, things did not go as planned. After about a month of relative inactivity, Cumberland moved his regulars into the Highlands. On 17 May three battalions of regulars and eight Highland companies reoccupied Fort Augustus. The same day the Macphersons surrendered. On the day of the planned rendezvous, Clanranald never appeared and Lochgarry and Barisdale only showed up with about 300 combined (most of whom immediately dispersed in search of food). Lochiel, who commanded possibly the strongest Jacobite unit at Culloden, was only able to muster about 300. The following morning Lochiel was alerted that a body of Highlanders was approaching. Assuming they were Barisdale's Macdonalds, Locheil waited until they were identified as Loudoun's by the "red crosses in their bonnets". Locheil's men dispersed without fighting. The following week the Government launched punitive expeditions into the Highlands which continued throughout the summer.[45][46]

Following his flight from the battle, Charles Edward Stuart made his way towards the Hebrides with some supporters. By 20 April, Stuart had reached Arisaig on the west coast of Scotland. After spending a few days with his close associates, Stuart sailed for the island of Benbecula in the Outer Hebrides. From there he travelled to Scalpay, off the east coast of Harris, and from there made his way to Stornoway.[47] For five months Stuart criss-crossed the Hebrides, constantly pursued by Government supporters and under threat from local lairds who were tempted to betray him for the £30,000 upon his head.[48] During this time he met Flora Macdonald, who famously aided him in a narrow escape to Skye. Finally, on 19 September, Stuart reached Borrodale on Loch nan Uamh in Arisaig, where his party boarded two small French ships, which ferried them to France.[47] He never returned to Scotland.

Repercussions and persecution

The morning following the Battle of Culloden, Cumberland issued a written order reminding his men that "the public orders of the rebels yesterday was to give us no quarter".[note 5] Cumberland alluded to the belief that such orders had been found upon the bodies of fallen Jacobites. In the days and weeks that followed, versions of the alleged orders were published in the Newcastle Journal and the Gentleman's Journal. Today only one copy of the alleged order to "give no quarter" exists.[50] It is however considered to be nothing but a poor attempt at forgery, for it is neither written nor signed by Murray, and it appears on the bottom half of a copy of a declaration published in 1745. In any event, Cumberland's order was not carried out for two days, after which contemporary accounts report then that for the next two days the moor was searched and all those wounded were put to death. On the other hand, the orders issued by Lord George Murray for the conduct of the aborted night attack in the early hours of 16 April suggest that it would have been every bit as merciless. The instructions were to use only swords, dirks and bayonets, to overturn tents, and subsequently to locate "a swelling or bulge in the fallen tent, there to strike and push vigorously".[50] [note 6] In total, over 20,000 head of livestock, sheep, and goats were driven off and sold at Fort Augustus, where the soldiers split the profits.[52]

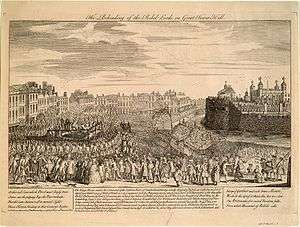

While in Inverness, Cumberland emptied the gaols that were full of people imprisoned by Jacobite supporters, replacing them with Jacobites themselves.[45] Prisoners were taken south to England to stand trial for high treason. Many were held on hulks on the Thames or in Tilbury Fort, and executions took place in Carlisle, York and Kennington Common.[48] The common Jacobite supporters fared better than the ranking individuals. In total, 120 common men were executed, one third of them being deserters from the British Army.[48] [note 7] The common prisoners drew lots amongst themselves and only one out of twenty actually came to trial. Although most of those who did stand trial were sentenced to death, almost all of these had their sentences commuted to transportation to the British colonies for life. In all, 936 men were thus transported, and 222 more were banished. Even so, 905 prisoners were actually released under the Act of Indemnity which was passed in June 1747. Another 382 obtained their freedom by being exchanged for prisoners of war who were held by France. Of the total 3,471 prisoners recorded nothing is known of the fate of 648.[55] The high ranking "rebel lords" were executed on Tower Hill in London.

Following up on the military success won by their forces, the British Government enacted laws to incorporate Scotland—specifically the Scottish Highlands—within the rest of Britain. Members of the Episcopal clergy were required to give oaths of allegiance to the reigning Hanoverian dynasty.[56] The Abolition of Heritable Jurisdictions Act of 1747 ended the hereditary right of landowners to govern justice upon their estates through barony courts.[57] Previous to this act, feudal lords (which included clan chiefs) had considerable judicial and military power over their followers—such as the oft quoted power of "pit and gallows".[48][56] Lords who were loyal to the Government were greatly compensated for the loss of these traditional powers, for example the Duke of Argyll was given £21,000.[48] Those lords and clan chiefs who had supported the Jacobite rebellion were stripped of their estates and these were then sold and the profits were used to further trade and agriculture in Scotland.[56] The forfeited estates were managed by factors. Anti-clothing measures were taken against the highland dress by an Act of Parliament in 1746. The result was that the wearing of tartan was banned except as a uniform for officers and soldiers in the British Army and later landed men and their sons.[58]

Culloden battlefield today

Today, a visitor centre is located near the site of the battle. This centre was first opened in December 2007, with the intention of preserving the battlefield in a condition similar to how it was on 16 April 1746.[60] One difference is that it currently is covered in shrubs and heather; during the 18th century, however, the area was used as common grazing ground, mainly for tenants of the Culloden estate.[61] Those visiting can walk the site by way of footpaths on the ground and can also enjoy a view from above on a raised platform.[62] Possibly the most recognisable feature of the battlefield today is the 20 feet (6.1 m) tall memorial cairn, erected by Duncan Forbes in 1881.[59] In the same year Forbes also erected headstones to mark the mass graves of the clans.[63] The thatched roofed farmhouse of Leanach which stands today dates from about 1760; however, it stands on the same location as the turf-walled cottage that probably served as a field hospital for Government troops following the battle.[61] A stone, known as "The English Stone", is situated west of the Old Leanach cottage and is said to mark the burial place of the Government dead.[64] West of this site lies another stone, erected by Forbes, marking the place where the body of Alexander McGillivray of Dunmaglass was found after the battle.[65][66] A stone lies on the eastern side of the battlefield that is supposed to mark the spot where Cumberland directed the battle.[67] The battlefield has been inventoried and protected by Historic Scotland under the Historic Environment (Amendment) Act 2011.[68]

.jpg)

Since 2001, the site of the battle has undergone topographic, geophysical, and metal detector surveys in addition to archaeological excavations. Interesting finds have been made in the areas where the fiercest fighting occurred on the Government left wing, particularly where Barrell's and Dejean's regiments stood. For example, pistol balls and pieces of shattered muskets have been uncovered here which indicate close quarters fighting, as pistols were only used at close range and the musket pieces appear to have been smashed by pistol/musket balls or heavy broadswords. Finds of musket balls appear to mirror the lines of men who stood and fought. Some balls appear to have been dropped without being fired, some missed their targets, and others are distorted from hitting human bodies. In some cases it may be possible to identify whether the Jacobites or Government soldiers fired certain rounds, because the Jacobite forces are known to have used a large quantity of French muskets which fired a slightly smaller calibre shot than that of the British Army's Brown Bess. Analysis of the finds confirms that the Jacobites used muskets in greater numbers than has traditionally been thought. Not far from where the hand-to-hand fighting took place, fragments of mortar shells have been found.[69] Though Forbes's headstones mark the graves of the Jacobites, the location of the graves of about sixty Government soldiers is unknown. The recent discovery of a 1752 silver Thaler, from the Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, may however lead archaeologists to these graves. A geophysical survey, directly beneath the spot where the coin was found, seems to indicate the existence of a large rectangular burial pit. It is thought possible that the coin was dropped by a soldier who once served on the continent, while he visited the graves of his fallen comrades.[69]

Order of battle: Culloden, 16 April 1746

Jacobite army

Charles Edward Stuart

Colonel John William Sullivan

| Division | Unit | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escort troop | Fitzjames' Horse: 16 men. Lifeguards: 16 men. |

Commanded by Capt O'Shea. This unit was the prince's escort. | |

| Lord George Murray's Division | Atholl Brigade: 500 men (3 battalions). | Raised not as a clan but as a feudal levy. Possibly consisted of 3 regiments. Suffered badly from desertion. | |

| Cameron of Lochiel's Regiment: abt 650–700 men.[70] | Led by Sir Donald Cameron of Lochiel. Regarded as one of the strongest Jacobite units, and as elite. | ||

| Stewarts of Appin or Appin Regiment: 250 men.[71] | Led by Charles Stuart of Ardsheal. The regiment suffered from desertion. During the campaign it suffered 90 killed, 65 wounded. | ||

| Lord John Drummond's Division. | Lord Lovat's Regiment: abt 300 men.[72] | Led at Culloden by Charles Fraser of Inverallochie, whose battalion was numbered at about 300. The Master of Lovat's battalion missed the battle by several hours.[73] | |

| Lady Mackintosh's Regiment: abt 350 men.[74] | Sometimes referred to in secondary sources as Clan Chattan Regiment. A composite unit, like the Athole Brigate. Led by Alexander McGillivray of Dunmaglass. Lost most of its officers at Culloden. | ||

| Farquharson of Monaltrie's Battalion: 150 men. | Consisted of mostly Highlanders but not all. Described by James Logie as "dressed in highland clothes mostly".[note 8] Included a party of MacGregors.[note 9] | ||

| Maclachlans and Macleans: abt 200 men.[77] | Commanded by Lachlan Maclachlan of Castle Lachlan and Maclean of Drimmin (who served as Lt Col). The unit campaigned as part of the Athole Brigade, though fought at Culloden for the first time as a stand-alone unit.[78] | ||

| Chisholms of Strathglass: abt 80 men.[79] | This very small unit was led by Roderick Og Chisholm. Suffered very heavy casualties at Culloden.[78] | ||

| Duke of Perth's Division. | MacDonald of Keppoch's Regiment. 200 men. | Commanded by Alexander MacDonald of Keppoch. This small regiment consisted of MacDonalds of Keppoch, MacDonalds of Glencoe,[note 10] Mackinnons and MacGregors.[note 11][78] | |

| MacDonald of Clanranald's Regiment: 200 men. | Commanded by MacDonald of Clanranald, younger, who was wounded during the battle. Disbanded at Fort Augustus about 18 April 1746.[78] | ||

| MacDonnell of Glengarry's Regiment: 500 men. | Commanded by Donald MacDonnell of Lochgarry. This regiment included a unit of Grants of Glenmoriston and Glen Urquhart.[note 12] | ||

| John Roy Stuart's Division (reserve) | Lord Lewis Gordon's Regiment | John Gordon of Avochie's Battalion: 300 men. | Commanded by John Gordon of Avochie.[note 13] |

| Moir of Stonywood's Battalion: 200 men. | Commanded by James Moir of Stonywood. The unit, unlike the others of this regiment, was made up largely of volunteers.[78] | ||

| 1/Lord Ogilvy's Regiment: 200 men. | Commanded by Thomas Blair of Glassclune. | ||

| 2/Lord Ogilvy's Regiment: 300 men. | Commanded by Sir James Johnstone. | ||

| John Roy Stuart's Regiment: abt 200 men. | Commanded by Maj Patrick Stewart. Also known as the Edinburgh Regiment, because of where it was raised.[note 14] | ||

| Footguards. abt 200 men. | Commanded by William, Lord Kilmarnock. A composite unit.[note 15] | ||

| Glenbuchet's Regiment. 200 men. | Commanded by John Gordon of Glenbuchat. | ||

| Duke of Perth's Regiment: 300 men. | James Drummond, Master of Strathallan. The unit included a party of MacGregors.[note 16] | ||

| Irish Brigade. | Garde Écossaise: 350 men. | Commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Lord Lewis Drummond. | |

| Irish Picquets: 302 men. | Commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Walter Stapleton. | ||

| Cavalry (Commanded by Sir John MacDonald of Fitzjames' Horse) |

Right Squadron | Fitzjames' Horse: 70 men. | Commanded by Capt William Bagot. |

| Lifeguards: 30 men. | Commanded by David, Lord Elcho. | ||

| Left Squadron | Scotch Hussars: 36 men. | Commanded by Maj John Bagot. | |

| Strathallan's Horse: 30 men. | Commanded by William, Lord Strathallan. | ||

|

Artillery. |

11 x 3-pounders. | Commanded by Capt John Finlayson. | |

| 1 x 4-pounders. | Commanded by Capt du Saussay. | ||

Government Army

Captain-General: HRH Duke of Cumberland

Commander-in-Chief North Britain: Lieutenant-General Henry Hawley

| Division | Unit | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escort troop | Duke of Cumberland's Hussars: abt 20 men. | Made up of Austrians and Germans. | |

| Advance Guard (Commanded by Maj-Gen Humphrey Bland) |

10th (Cobham's) Dragoons: 276 officers & men. | Commanded by Maj Peter Chaban. | |

| 11th (Kerr's) Dragoons: 267 officers & men. | Commanded by Lt Col William, Lord Ancram. | ||

| Loudon's Highlanders (64th Foot): abt 300 rank and file. | Commanded by Lt Col John Campbell, 5th Duke of Argyll | ||

| Front Line (1st Division) (Maj-Gen. William Anne, Earl of Albermarle) |

First Brigade | 2/1st (Royal) Regiment: 401 rank & file. | Commanded by Lt Col John Ramsay. |

| 34th (Cholmondley's) Foot: 339 rank & file. | Commanded by Lt Col Charles Jeffreys. | ||

| 14th (Price's) Foot: 304 rank & file. | Commanded by Lt Col John Grey. | ||

| Third Brigade | 21st (North British) Fusiliers: 358 rank & file. | Commanded by Maj Hon. Charles Colvill. | |

| 37th (Dejean's) Foot: 426 rank & file. | Commanded by Col Louis Dejean. | ||

| 4th (Barrell's) Foot: 325 rank & file. | Commanded by Lt Col Robert Rich. | ||

| Second Line (Commanded by Gen John Huske) |

Second Brigade | 3rd Foot (Buffs): 413 rank & file. | Commanded by Lt Col George Howard. |

| 36th (Fleming's) Foot: 350 rank & file. | Commanded by Lt Col George Jackson. | ||

| 20th (Sackville's) Foot: 412 rank & file. | Commanded by Col Lord George Sackville. | ||

| Fourth Brigade | 25th (Sempill's) Foot: 429 rank & file. | Commanded by Lt Col David Cunynghame. | |

| 59th (Conway's) Foot: 325 rank & file. | Commanded by Col Hon. Henry Conway. | ||

| 8th (Edward Wolfe's) Foot: 324 rank & file. | Commanded by Lt Col Edward Martin. | ||

| Reserve | Duke of Kingston's 10th Horse: 211 officers & men. | Commanded by Lt Col Hon. John Mordaunt. | |

| Fifth Brigade (Brig John Mordaunt) |

13th (Pulteney's) Foot: 510 rank & file. | Commanded by Lt Col Thomas Cockayne. | |

| 62nd (Batereau's) Foot: 354 rank & file. | Commanded by Col John Batereau. | ||

| 27th (Blakeney's) Foot: 300 rank & file. | Commanded by Lt Col Francis Leighton. | ||

| Artillery | 106 NCOs & Gunners 10 x 3-pounder cannon 6 x Coehorn mortars |

Commanded by Commander Royal Artillery (CRA): Maj William Belford and Captain-Lieutenant John Godwin. | |

See the following reference for source of tables[84]

- Of the 16 British infantry battalions, 11 were English, 4 were Scottish (3 Lowland + 1 Highland), and 1 Irish battalion.

- Of the 3 British battalions of horse (dragoons), 2 were English and 1 was Scottish.

British Army casualties

| Regiment | Killed | Wounded |

|---|---|---|

| 1st (Royal) Regiment | 0 | 4 |

| 3rd Foot (Buffs)[85] | 1 | 2 |

| 4th (Barrell's) Foot | 17 | 108 |

| 8th (Wolfe's) Foot | 0 | 1 |

| 13th (Pulteney's) Foot | 0 | 0 |

| 14th (Price's) Foot | 1 | 9 |

| 20th (Sackville's) Foot[86] | 4 | 17 |

| 21st (North British) Fusiliers[87] | 0 | 7 |

| 25th (Sempill's) Foot | 1 | 13 |

| 13th (Pulteney's) Foot | 0 | 0 |

| 34th (Cholmondley's) Foot | 1 | 2 |

| 36th (Fleming's) Foot | 0 | 6 |

| 37th (Dejean's) Foot | 14 | 68 |

| 59th (Conway's) Foot [note 17] | 1 | 5 |

| 62nd (Batereau's) Foot | 0 | 3 |

| 64th (Loudon's) Foot | 6 | 3 |

| Argyll Militia | 0 | 1 |

| Royal Artillery | 0 | 6 |

| Duke of Kingston's 10th Horse | 0 Horses: 2 |

1 Horses: 1 |

| 10th (Cobham's) Dragoons | 1 Horses: 4 |

0 Horses: 5 |

| 11th (Kerr's) Dragoons | 3 Horses: 4 |

3 Horses: 15 |

See following reference for source of table[88]

The Battle of Culloden in art

- An Incident in the Rebellion of 1745, by David Morier, often known as "The Battle of Culloden", is the best-known portrayal of the battle, and the best-known of Morier's works. It depicts the attack of the Highlanders against Barrell's Regiment, and is based on sketches made by Morier in the immediate aftermath of the battle.

- Augustin Heckel's The Battle of Culloden (1746; reprinted 1797) is held by the National Galleries of Scotland.[89]

The Battle of Culloden and consequent imprisonment and execution of the Jacobite prisoners of war is depicted in the song "Tam kde teče řeka Flee" ("Where the Big Water Fleet flows") by the Czech Celtic-rock band Hakka Muggies.

- SUMO The Italo-Argentine band Sumo made a song titled Crua Chan, perfectly chronicling the development of the battle. The work was composed by Italian Luca Prodan, bandleader; he had knowledge of the battle in his student years in England.

- Frank Watson Wood, (1862-1953). Although he was better known as a Naval artist who mainly painted in water colours Frank Watson Wood painted The Highland Charge at the Battle of Culloden in oil. Frank Watson Wood exhibited at Royal Scotland Academy, The Royal society of painters in water Colours and The Royal Academy.

The Battle of Culloden in fiction

- The Battle of Culloden is an important episode in D. K. Broster's The Flight of the Heron (1925), the first volume of her Jacobite Trilogy, which been made into a TV serial twice: by Scottish Television in eight episodes in 1968, and by the BBC in 1976.

- Naomi Mitchison's novel The Bull Calves (1947) deals with Culloden and its aftermath.[90]

- Culloden (1964) depicts the battle in the style of 20th-century television reporting.

- Dragonfly in Amber by Diana Gabaldon (1992, London) is a detailed fictional tale, based on historical sources, of the Scots, High and Lowlanders, mostly the Highlanders within Clan Fraser. It has the element of time travel, with the 20th Century protagonist knowing how the battle would turn out and still – once transported to the 18th century – caught up in the foredoomed struggle.

- The Highlanders is the fourth serial of the fourth season (and the 31st story overall) in the British science fiction television series Doctor Who. The Second Doctor and his companions Polly and Ben Jackson arrive in the TARDIS in the hours after the Battle of Culloden. They are persecuted by the British forces for helping survivors of the Scottish Clans. At the end of the story, one of the survivors, a young piper named Jamie McCrimmon joins the Doctor in travels through time and space. The Highlanders was broadcast in four weekly parts from 17 December 1966 to 7 January 1967. The episodes no longer exist, except as censored film clips, audio recordings, and off-air photographs.

- Drummossie Moor – Jack Cameron, The Irish Brigade and the battle of Culloden is a historical novel by Ian Colquhoun (Arima/Swirl, 2008) which tells the story of the battle and the preceding days from the point of view of the Franco-Irish regulars or 'Piquets' who covered the Jacobite retreat.[91]

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Colonel John William Sullivan wrote, "All was confused ... such a chiefe of a tribe had sixty men, another thiry, another twenty, more or lesse; they would not mix nor seperat, & wou'd have double officers, yt is two Captns & two Lts, to each Compagny, strong or weak ... but by little, were brought into a certain regulation".[12]

- ↑ An unknown British Army corporal's description of the charge into the Government's left wing: "When we saw them coming towards us in great Haste and Fury, we fired at about 50 Yards Distance, which made Hundreds fall, we fired at about 50 Yards Distance, which made Hundreds fall; notwithstanding which, they were so numerous, that they still advanced, and were almost upon us before we had loaden again. We immediately gave them another full Fire and the Front Rank charged their Bayonets Breast high, and the Center and Rear Ranks kept up a continual Firing, which, in half an Hour's Time, routed their whole Army. Only Barrel's Regiment and ours was engaged, the Rebels designing to break or flank us but our Fire was so hot, most of us having discharged nine Shot each, that they were disappointed".

- ↑ James Johnstone, a member of Glengarry's Regiment wrote that the ground was "covered with water which reached halfway up the leg".[38]

- ↑ Cumberland wrote of the Macdonalds: "They came running on in their wild manner, and upon the right where I had place myself, imagining the greatest push would be there, they came down there several times within a hundred yards of our men, firing their pistols and brandishing their swords, but the Royals and Pulteneys hardly took their fire-locks from their shoulders, so that after those faint attempts they made off; and the little squadrons on our right were sent to pursue them".[39]

- ↑ Cumberland wrote: "A captain and fifty foot to march directly and visit all the cottages in the neighbourhood of the field of battle, and search for rebels. The officers and men will take notice that the public orders of the rebels yesterday was to give us no quarter".[49]

- ↑ A Highland Jacobite officer wrote: "We were likewise forbid in the attack to make use of firearms, but only of sword, dirk and bayonet, to cutt the tent strings, and pull down the poles, and where observed a swelling or bulge in the falen tent, there to strick and push vigorously".[51]

- ↑ Out of 27 officers of the English "Manchester Regiment": one died in prison; one was acquitted; one was pardoned; two were released for giving evidence; four escaped; two were banished; three were transported; and eleven were executed. The sergeants of the regiment suffered worse, with seven out of ten hanged. At least seven privates were executed, some no doubt died in prison, and most of the rest were transported to the colonies.[54]

- ↑ Farquharson of Monaltrie's Battalion is sometimes referred to as the "Mar" battalion of Lord Lewis Gordon's Regiment, and raised in Braemar and upper Deeside by Francis Farquharson of Monaltrie.[75]

- ↑ This party of MacGregors were attached to Farquharson of Monaltrie's battalion of Lord Lewis Gordon's Regiment. They were commanded by MacGregor of Inverenzie.[76]

- ↑ Attached to the MacDonald of Keppoch's Regiment was MacDonald of Glencoe's Regiment. It joined the Jacobite army on 27 August 1745 and served the rest of the campaign attached to MacDonald of Keppoch's Regiment. This was a very small unit, of no more than 120 men, and was commanded by Alexander MacDonald of Glencoe. It surrendered to General Campbell on 12 May 1746 and had suffered 52 killed, 36 wounded. Instead of a regimental standard, the regiment is said to have marched behind a bunch of heather attached to a pike.[80]

- ↑ MacGregors serving in MacDonald of Keppoch's Regiment were commanded by John MacGregor of Glengyle.[76]

- ↑ Grant of Glenmoriston's Battalion was a very small unit of abt 80–100 men, from Glenmoriston and Glen Urquhart. The unit was commanded by Maj Patrick Grant of Glenmoriston and Alexander Grant, younger of Shewglie. About 30 men from this unit were killed at Culloden, though both Glenmoriston and Shewglie, younger escaped. Almost all of the 87 of the men from this unit who surrendered on 4 May were transported.[81]

- ↑ Sometimes referred to as the "Strathbogie" Battalion of Lord Lewis Gordon's Regiment. Many of the 300 men were highlanders, though most feudal levies and mercenaries – not clansmen. An intelligence report of 11 December 1745 stated that of the 300 men, "only 100 have joined; mostly herds and hiremen from about Strathbogie and unaquainted with the use of arms; many are pressed and intend to desert ...".[81]

- ↑ The unit was recruited in Edinburgh, by Stuart who was a captain in the Royal Écossais at the time. For a time the unit included some former members of the British Army. At the battle it eventually stood in the front, next to the Stewarts of Appin.[82]

- ↑ A composite regiment formed in March 1746 by combining the dismounted Lord Kilmarnock's Horse, Lord Pisligo's Horse, and James Crichton of Auchingoul's Regiment, as well as forced recruits from Aberdeenshire courtesy of Lady Erroll (mother-in-law to Lord Kilmarnock).[83]

- ↑ At least two companies of MacGregors, commanded by James Mor Drummond, served in the Duke of Perth's Regiment.[76]

- ↑ Renamed the 48th Foot in 1748.[18]

Notes

- ↑ Site Record for Culloden Moor, Battlefield; Culloden Muir; Culloden Battlefield; Battle Of Culloden. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Pittock (2016).

- 1 2 Harrington (1991), p. 83.

- ↑ "The Making of the Union". Retrieved 14 June 2009.

- ↑ McGarry,Stephen, Irish Brigades Abroad Dublin 2013.

- ↑ Anderson, Peter (1920). Culloden Moor and story of the battle. Oxford: E. Mackay. p. 16.

- ↑ Pollard, Tony. Culloden: The History and Archaeology of the last Clan Battle. Published 2009. ISBN 1-84884-020-9.

- ↑ Thompson, p. 148; Trench, pp. 217–223.

- ↑ Harrington (1991), p. 53.; also Reid (2997), p. 45.

- 1 2 3 Barthorp (1982), p. 17–18.

- ↑ Harrington (1991), pp. 35–40.

- ↑ Reid (2006), pp. 20–21.

- 1 2 Reid (1997), p. 58.

- 1 2 Reid (2006), pp. 20–22.

- ↑ Reid (1997), p. 50.

- 1 2 Harrington (1991), pp. 40–43.

- 1 2 Reid (2006), pp. 22–23.

- 1 2 Reid (2002), p. author's note.

- ↑ Harrington (1991), pp. 25–29.

- ↑ Harrington (1991), pp. 29–33.

- ↑ Harrington (1991), p. 33.

- 1 2 Harrington (1991), p. 44.

- ↑ Reid (2002), p. 51–56.

- ↑ "Map of Drummossie". MultiMap.

- ↑ "Map of Drummossie Moor". MultiMap.

- ↑ "Map of Culloden". MultiMap.

- ↑ Get map, UK: Ordnance Survey.

- 1 2 Reid (2002), pp. 56–58.

- ↑ Britain as a military power 1688–1815 (1999) – Page 32

- ↑ Black,Jeremy, Culloden and the '45(1990)

- 1 2 Harrington (1991), p. 47.

- ↑ Roberts (2002), p. 168.

- 1 2 3 Reid (2002), pp. 58–68.

- ↑ Reid (2002), pp. 68–72.

- ↑ Reid (2002), p. 72.

- ↑ Reid (1996) British Redcoat 1740–1793, pp. 9, 56–58.

- ↑ Roberts (2002), p. 173.

- ↑ Reid (2002), p. 73.

- ↑ Roberts (2002), p. 173.; also Reid (2002), p. 77.

- ↑ Reid (2002), pp. 72–80.

- ↑ McGarry, Irish Brigades Abroad p. 122

- 1 2 3 Reid (2002), pp.80–85.

- ↑ Reid (2006), p. 16.

- ↑ Reid (2002), p. 93.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Reid (2002), pp. 88–90.

- 1 2 Roberts (2002), p. 182–183.

- 1 2 Harrington (1991), p. 85–86.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Prebble (1973), p. 301.

- ↑ Roberts (2002), p. 178.

- 1 2 Roberts (2002), pp. 177–80.

- ↑ Lockhart (1817), p. 508.

- ↑ Magnusson (2003), p. 623.

- ↑ Harrington (1996), p. 88.

- ↑ Monod (1993), p. 340.

- ↑ Roberts (2002), pp. 196–197.

- 1 2 3 "Britain from 1742 to 1754". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- ↑ Brown (1997), p. 133.

- ↑ Gibson (2002), pp. 27–28.

- 1 2 "The Memorial Cairn". Culloden Battlefield Memorial Project. Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- ↑ "New Visitor Centre". Culloden Battlefield Memorial Project. Archived from the original on 18 August 2008. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- 1 2 Reid (2002), pp. 91–92.

- ↑ "What's New?". Culloden Battlefield Memorial Project. Archived from the original on 19 October 2008. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- 1 2 "Graves of the clans". Culloden Battlefield Memorial Project. Archived from the original on 14 April 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- ↑ "Field of the English". Culloden Battlefield Memorial Project. Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- ↑ "Well of the dead". Culloden Battlefield Memorial Project. Archived from the original on 27 June 2008. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- ↑ "'The Well of the Dead', Culloden Battlefield". www.ambaile.org.uk (ambaile.org.uk). Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- ↑ "Cumberland stone". Culloden Battlefield Memorial Project. Archived from the original on 4 June 2008. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- ↑ "Inventory battlefields". Historic Scotland. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- 1 2 "Point of Contact: Archaeology at Culloden". University of Glasgow Centre for Battlefield Archaeology. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

- ↑ Reid gives "650" in Reid (2002), p. 26.; however he gives "about 700" in Reid (2006), p. 16.

- ↑ Reid gives 150 in Reid (2002), p. 26.; however he states "The unit was just 250 strong at Culloden" in Reid (2006), p. 25.

- ↑ Reid gives "500" in Reid (2002), p. 26.; he states that Inverallochie's battalion that took part in the battle numbered "about 300".

- ↑ Reid (2006), p. 20.

- ↑ Reid gives "500'" in Reid (2002), p. 26.; however gives "Some 300 strong at Falkirk, and about 350 strong at Culloden" in Reid (2006), p. 22.

- ↑ Reid (2006), p. 18.

- 1 2 3 Reid (2006), p. 22.

- ↑ Reid gives 182 in Reid (2002), p. 26; however states the unit was "apparently with a strength of some 200 men" in Reid (2006), p. 22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Reid (2006), pp. 15–26.

- ↑ Reid gives 100 in Reid (2002) p. 26.; however states "no more than about 80 strong" in Reid (2006) p. 17.

- ↑ Reid (2006), p. 21.

- 1 2 Reid (2006), p. 19.

- ↑ Reid (2006), p. 26.

- ↑ Reid (2006), p. 19–20.

- ↑ Unless noted elsewhere, units and unit sizes are from, Reid (2002), pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Reid lists this as "Howard's", Reid (1996), p. 195.; and "Howard's (3rd)", Reid (1996), p. 196.

- ↑ Reid lists this as "Bligh's", Reid (1996), p. 195.; and "Bligh's (20th)", Reid (1996), p. 197.

- ↑ Reid lists this as "Campbells", Reid (1996), p. 195.; and "Campbell's (21st)", Reid (1996), p. 197.

- ↑ Reid (1996), pp. 195–198.

- ↑ "Augustin Heckel: The Battle of Culloden". National Galleries of Scotland. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ↑ Cairns, Craig (2012). Devine, T M; Wormald, Jenny, eds. The Literary Tradition. The Oxford handbook of modern Scottish history. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-19-956369-2.

- ↑ Colquhoun, Ian (2008). Drummossie Moor – Jack Cameron, The Irish Brigade and the Battle of Culloden. Swirl. ISBN 1-84549-281-1.

Bibliography

- McGarry, Stephen (2013). Irish Brigades Abroad. The History Press. ISBN 978-1-84588-799-5.

- Barthorp, Michael (1982). The Jacobite Rebellions 1689–1745. Men-at-arms series. 118. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 0-85045-432-8.

- Brown, Stewart J. (1997). William Robertson and the Expansion of Empire. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-57083-2.

- Patterson, Raymond Campbell (1998). A Land Afflicted: Scotland & the Covenanter Wars, 1638–90.

- Cowan, Ian (1976). The Scottish Covenanters, 1660–1688. London.

- Duffy, Christopher (2003). The '45: Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Untold Story of the Jacobite Rising. Cassel. ISBN 0-304-35525-9.

- Harrington, Peter (1991). Chandler, David G., ed. Culloden 1746, The Highland Clans' Last Charge. Campaign series. 12. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-85532-158-0.

- Gibson, John G. (2002). Old and New World Highland Bagpiping. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-2291-3.

- Harris, Tim (2005). Restoration: Charles II and his Kingdoms, 1660–1685. London.

- Harris, Tim (2006). Revolution: The Great Crisis of the British Monarchy, 1685–1720. London.

- Lockhart, George (1817). The Lockhart papers: containing memoirs and commentaries upon the affairs of Scotland from 1702 to 1715. 2. London.

- Maclean, Fitzroy (1991). Scotland, A Concise History. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27706-0.

- Magnusson, Magnus (2003). Scotland: The Story of a Nation. Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-3932-9.

- Monod, Paul Kleber (1993). Jacobitism and the English People, 1688–1788. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44793-3.

- Pickering, W. (ed.) (1881). An Old Story Re-told From The "Newcastle Courant". The Rebellion of 1745.

- Prebble, John (1962). Culloden. Atheneum.

- Prebble, John (1973). The Lion in the North. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-003652-0.

- Reid, Stuart (1996). British Redcoat 1740–1793. Warrior series. 19. London: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-85532-554-3.

- Reid, Stuart (1996). 1745, A Military History of the Last Jacobite Rising. Sarpedon. ISBN 1-885119-28-3.

- Reid, Stuart (1997). Highland Clansman 1689–1746. Warrior series. 21. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-85532-660-4.

- Reid, Stuart (2002). Culloden Moor 1746: The Death of the Jacobite Cause. Campaign series. 106. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-412-4.

- Reid, Stuart (2006). The Scottish Jacobite Army 1745–46. Elite series. 149. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84603-073-0.

- Roberts, John Leonard (2002). The Jacobite Wars: Scotland and the Military Campaigns of 1715 and 1745. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 1-902930-29-0.

- Sadler, John (2006). Culloden: The Last Charge of the Highland Clans. NPI Media Group. ISBN 0-7524-3955-3.

- Smith, Hannah (2006). Georgian Monarchy: Politics and Culture. Cambridge University Press.

- Smurthwaite, David (1984). Ordnance Survey Complete Guide to the Battlefields of Britain. Webb & Bower.

- Thompson, Andrew C. (2011) George II: King and Elector. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11892-6

- Trench, Charles Chevenix (1975) George II. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 0-7139-0481-X

- Film and documentaries

- Watkins, Peter (director/writer) (15 December 1964). Culloden. BBC.

- "Culloden: The Jacobites' Last Stand". Battlefield Britain. 2004. BBC.

Further reading

Black, Jeremy (April 2002). Culloden and the '45. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5636-2.

The Battle of Culloden (TV Movie, BBC, 1964), http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0057982/

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Culloden. |

- Culloden Battlefield Memorial Project

- Cumberland's dispatch from the battle, published in the London Gazette

- Ascanius; or, the Young Adventurer

- Culloden Moor and the Story of the Battle (1867 account)

- Controversy over the redevelopment of the NTS visitor centre at Culloden

- A personal account of the battle.

- Battle of Culloden Moor

- Ghosts of Culloden including the Great Scree and Highlander Ghost

- The "French Stone" at Culloden

- Maps

- "A plan of the battle of Coullodin moore fought on the 16th of Aprile 1746", by Daniel Paterson, 1746

- "Plan of the Battle of Culloden", by Anon, ca 1748

- "Plan of the battle of Collodin ...", by Jasper Leigh Jones, 1746

- "A plan of the Battle of Culloden and the adjacent country, shewing the incampment of the English army at Nairn and the march of the Highlanders in order to attack them by night", by John(?) Finlayson, 1746(?)