Coronary circulation

| Coronary circulation | |

|---|---|

|

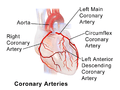

Coronary arteries labeled in red text and other landmarks in blue text. | |

| Details | |

| Artery | red |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | A07.231.114.269 |

Coronary circulation is the circulation of blood in the blood vessels of the heart muscle myocardium known as coronary arteries. The vessels that remove the deoxygenated blood from the heart muscle are known as cardiac veins. These include the great cardiac vein, the middle cardiac vein, the small cardiac vein and the anterior cardiac veins.

As the left and right coronary arteries run on the surface of the heart, they can be called epicardial coronary arteries. These arteries, when healthy, are capable of autoregulation to maintain coronary blood flow at levels appropriate to the needs of the heart muscle. These relatively narrow vessels are commonly affected by atherosclerosis and can become blocked, causing angina or a heart attack. (See also: circulatory system.) The coronary arteries that run deep within the myocardium are referred to as subendocardial.

The coronary arteries are classified as "end circulation", since they represent the only source of blood supply to the myocardium; there is very little redundant blood supply, which is why blockage of these vessels can be so critical.

Structure

Coronary arteries supply blood to the myocardium and other components of the heart. Two coronary arteries originate from the left side of the heart at the beginning (root) of the aorta, just after the aorta exits the left ventricle. There are three dilations in the wall of the aorta just superior to the aortic semilunar valve. Two of these, the left posterior aortic sinus and anterior aortic sinus, give rise to the left and right coronary arteries, respectively. The third sinus, the right posterior aortic sinus, typically does not give rise to a vessel. Coronary vessel branches that remain on the surface of the artery and follow the sulci of the heart are called epicardial coronary arteries.[1]

The left coronary artery distributes blood to the left side of the heart, the left atrium and ventricle, and the interventricular septum. The circumflex artery arises from the left coronary artery and follows the coronary sulcus to the left. Eventually, it will fuse with the small branches of the right coronary artery. The larger anterior interventricular artery, also known as the left anterior descending artery (LAD), is the second major branch arising from the left coronary artery. It follows the anterior interventricular sulcus around the pulmonary trunk. Along the way it gives rise to numerous smaller branches that interconnect with the branches of the posterior interventricular artery, forming anastomoses. An anastomosis is an area where vessels unite to form interconnections that normally allow blood to circulate to a region even if there may be partial blockage in another branch. The anastomoses in the heart are very small. Therefore, this ability is somewhat restricted in the heart so a coronary artery blockage often results in myocardial infarction causing death of the cells supplied by the particular vessel.[1]

The right coronary artery proceeds along the coronary sulcus and distributes blood to the right atrium, portions of both ventricles, and the heart conduction system. Normally, one or more marginal arteries arise from the right coronary artery inferior to the right atrium. The marginal arteries supply blood to the superficial portions of the right ventricle. On the posterior surface of the heart, the right coronary artery gives rise to the posterior interventricular artery, also known as the posterior descending artery. It runs along the posterior portion of the interventricular sulcus toward the apex of the heart, giving rise to branches that supply the interventricular septum and portions of both ventricles.[1]

Anastomoses

There are some anastomoses between branches of the two coronary arteries. However the coronary arteries are functionally end arteries and so these meetings are referred to as anatomical anastamoses, which lack function, as opposed to functional or physiological anastomoses like that in the palm of the hand. This is because blockage of one coronary artery generally results in death of the heart tissue due to lack of sufficient blood supply from the other branch. When two arteries or their branches join, the area of the myocardium receives dual blood supply. These junctions are called anastomoses. If one coronary artery is obstructed by an atheroma, the second artery is still able to supply oxygenated blood to the myocardium. However, this can only occur if the atheroma progresses slowly, giving the anastomoses a chance to proliferate.

Under the most common configuration of coronary arteries, there are three areas of anastomoses. Small branches of the LAD (left anterior descending/anterior interventricular) branch of the left coronary join with branches of the posterior interventricular branch of the right coronary in the interventricular groove. More superiorly, there is an anastomosis between the circumflex artery (a branch of the left coronary artery) and the right coronary artery in the atrioventricular groove. There is also an anastomosis between the septal branches of the two coronary arteries in the interventricular septum. The photograph shows area of heart supplied by the right and the left coronary arteries.

Variation

The left and right coronary arteries occasionally arise by a common trunk, or their number may be increased to three; the additional branch being the posterior coronary artery (which is smaller in size). In rare cases, a person will have the third coronary artery run around the root of the aorta.

Occasionally, a coronary artery will exist as a double structure (i.e. there are two arteries, parallel to each other, where ordinarily there would be one).

Coronary artery dominance

The artery that supplies the posterior descending artery (PDA)[2] determines the coronary dominance.[3]

- If the posterior descending artery is supplied by the right coronary artery (RCA), then the coronary circulation can be classified as "right-dominant".

- If the posterior descending artery is supplied by the circumflex artery (CX), a branch of the left artery, then the coronary circulation can be classified as "left-dominant".

- If the posterior descending artery is supplied by both the right coronary artery and the circumflex artery, then the coronary circulation can be classified as "co-dominant".

Approximately 70% of the general population are right-dominant, 20% are co-dominant, and 10% are left-dominant.[3] A precise anatomic definition of dominance would be the artery which gives off supply to the AV node i.e. the AV nodal artery. Most of the time this is the right coronary artery.

Function

Supply to papillary muscles

The papillary muscles attach the mitral valve (the valve between the left atrium and the left ventricle) and the tricuspid valve (the valve between the right atrium and the right ventricle) to the wall of the heart. If the papillary muscles are not functioning properly, the mitral valve may leak during contraction of the left ventricle. This causes some of the blood to travel "in reverse", from the left ventricle to the left atrium, instead of forward to the aorta and the rest of the body. This leaking of blood to the left atrium is known as mitral regurgitation. Similarly, the leaking of blood from the right ventricle through the tricuspid valve and into the right atrium can also occur, and this is described as tricuspid insufficiency or tricuspid regurgitation.

The anterolateral papillary muscle more frequently receives two blood supplies: left anterior descending (LAD) artery and the left circumflex artery (LCX).[4] It is therefore more frequently resistant to coronary ischemia (insufficiency of oxygen-rich blood). On the other hand, the posteromedial papillary muscle is usually supplied only by the PDA.[4] This makes the posteromedial papillary muscle significantly more susceptible to ischemia. The clinical significance of this is that a myocardial infarction involving the PDA is more likely to cause mitral regurgitation.

Changes in diastole

During contraction of the ventricular myocardium (systole), the subendocardial coronary vessels (the vessels that enter the myocardium) are compressed due to the high ventricular pressures. This compression results in momentary retrograde blood flow (i.e., blood flows backward toward the aorta) which further inhibits perfusion of myocardium during systole. However, the epicardial coronary vessels (the vessels that run along the outer surface of the heart) remain open. Because of this, blood flow in the subendocardium stops during ventricular contraction. As a result, most myocardial perfusion occurs during heart relaxation (diastole) when the subendocardial coronary vessels are open and under lower pressure. Flow never comes to zero in the right coronary artery, since the right ventricular pressure is less than the diastolic blood pressure.

Changes in oxygen demand

The heart regulates the amount of vasodilation or vasoconstriction of the coronary arteries based upon the oxygen requirements of the heart. This contributes to the filling difficulties of the coronary arteries. Compression remains the same. Failure of oxygen delivery caused by a decrease in blood flow in front of increased oxygen demand of the heart results in tissue ischemia, a condition of oxygen deficiency. Brief ischemia is associated with intense chest pain, known as angina. Severe ischemia can cause the heart muscle to die from hypoxia, such as during a myocardial infarction. Chronic moderate ischemia causes contraction of the heart to weaken, known as myocardial hibernation.

In addition to metabolism, the coronary circulation possesses unique pharmacologic characteristics. Prominent among these is its reactivity to adrenergic stimulation. The majority of vasculature in the body constricts in response to norepinephrine, a sympathetic neurotransmitter that the body uses to increase blood pressure. In the coronary circulation, however, norepinephrine vasoconstriction, due to the predominance of beta-adrenergic receptors in the coronary circulation. However, metabolic control factors will increase as a result of increased oxygen demand in the heart and will more greatly influence vasodilation. Thus sympathetic innervation to the coronary arteries ultimately causes vasodilation.

Branches

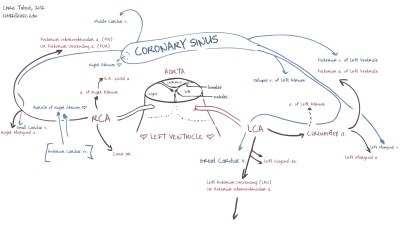

The following are the named branches of the coronary circulation in a right-dominate heart:

- Aorta

- Left coronary artery / Left main coronary artery (LMCA)

- Left circumflex artery (LCX)

- Obtuse marginal artery #1 (OM1)

- Obtuse marginal artery #2 (OM2)

- Left anterior descending artery (LAD)

- Diagonal artery #1

- Diagonal artery #2

- Left circumflex artery (LCX)

- Right coronary artery (RCA)

- AV node artery

- Right marginal artery

- Posterior descending artery (PDA)

- Posteriolateral artery #1 (PL#1)

- Posteriolateral artery #2 (PL#2)

- Left coronary artery / Left main coronary artery (LMCA)

Additional images

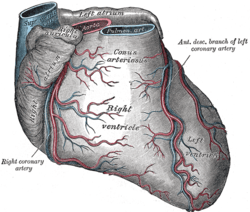

Anterior view of coronary circulation

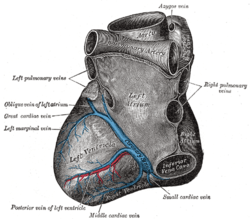

Anterior view of coronary circulation Posterior view of coronary circulation

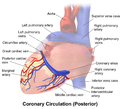

Posterior view of coronary circulation Illustration of coronary arteries

Illustration of coronary arteries

References

This article incorporates text from the CC-BY book: OpenStax College, Anatomy & Physiology. OpenStax CNX. 30 jul 2014..

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coronary circulation. |

- 1 2 3 Betts, J. Gordon (2013). Anatomy & physiology. pp. 787–846. ISBN 1938168135. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ↑ 00460 at CHORUS

- 1 2 Fuster, V; Alexander RW; O'Rourke RA (2001). Hurst's The Heart (10th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 53. ISBN 0-07-135694-0.

- 1 2 Voci P, Bilotta F, Caretta Q, Mercanti C, Marino B (1995). "Papillary muscle perfusion pattern. A hypothesis for ischemic papillary muscle dysfunction". Circulation. 91 (6): 1714–8. doi:10.1161/01.cir.91.6.1714. PMID 7882478.