Corticobasal degeneration

| Corticobasal degeneration - CBD | |

|---|---|

| |

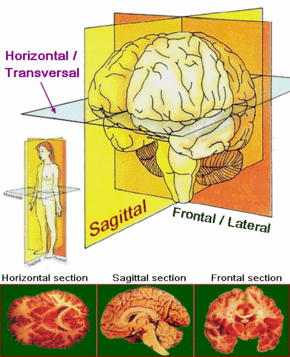

| Key anatomical plans and axes applied to sections of the brain. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-9-CM | 331.6 |

| DiseasesDB | 33284 |

| eMedicine | neuro/77 |

Corticobasal degeneration (CBD) or corticobasal ganglionic degeneration (CBGD) is a rare, progressive neurodegenerative disease involving the cerebral cortex and the basal ganglia.[1] CBD symptoms typically begin in people from 50–70 years of age, and the average disease duration is six years. It is characterized by marked disorders in movement and cognitive dysfunction, and is classified as one of the Parkinson plus syndromes. Clinical diagnosis is difficult, as symptoms of CBD are often similar to those of other disorders, such as Parkinson's disease (PD), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB).

Due to the various clinical presentations associated with CBD, a final diagnosis can only be made upon neuropathologic examination. Patients who are suffering from this disorder can learn more about CBD and reach out to others with the same condition for support, through The Foundation for PSP | CBD and Related Brain Diseases, also known as CurePSP.

Symptoms and clinical presentation

Because CBD is progressive, a standard set of diagnostic criteria can be used, which is centered on the disease’s evolution. Included in these fundamental features are problems with cortical processing, dysfunction of the basal ganglia, and a sudden and detrimental onset.[2] Psychiatric and cognitive dysfunctions, although present in CBD, are much less prevalent and lack establishment as common indicators of the presence of the disease.[3]

Motor and associated cortical dysfunctions

Some of the most prevalent symptom types in people exhibiting CBD pertain to identifiable movement disorders and problems with cortical processing. These symptoms are initial indicators of the presence of the disease. Each of the associated movement complications typically appear asymmetrically and the symptoms are not observed uniformly throughout the body. For example, a person exhibiting an alien hand syndrome (explained later) in one hand, will not correspondingly display the same symptom in the contralateral limb. Predominant movement disorders and cortical dysfunctions associated with CBD include:

- Parkinsonism

- Alien hand syndrome

- Apraxia (ideomotor apraxia and limb-kinetic apraxia)

- Aphasia[3]

Parkinsonism

The presence of parkinsonism as a clinical symptom of CBD is largely responsible for complications in developing unique diagnostic criteria for the disease.[4] Other such diseases in which parkinsonism forms an integral diagnostic characteristic are PD and PSP. Parkinsonism in CBD is largely present in an extremity such as the arm, and is always asymmetric. It has been suggested that non-dominant arm is involved more often.[5] Common associated movement dysfunctions that comprise parkinsonism are rigidity, bradykinesia, and gait disorder, with limb rigidity forming the most typical manifestation of parkinsonism in CBD. Despite being relatively indistinct, this rigidity can lead to disturbances in gait and correlated movements. Bradykinesia in CBD occurs when there is notable slowing in the completion of certain movements in the limbs. In an associated study, it was determined that, three years following first diagnosis, 71% of persons with CBD demonstrate the presence of bradykinesia.[3]

Alien hand syndrome

Alien hand syndrome has been shown to be prevalent in roughly 60% of those people diagnosed with CBD.[6] This disorder involves the failure of an individual to control the movements of his or her hand, which results from the sensation that the limb is “foreign.”[2] The movements of the alien limb are a reaction to external stimuli and do not occur sporadically or without stimulation. The presence of an alien limb has a distinct appearance in CBD, in which the diagnosed individual may have a “tactile mitgehen.” This mitgehen (German, meaning “to go with”) is relatively specific to CBD, and involves the active following of an experimenter’s hand by the subject’s hand when both hands are in direct contact. Another, rarer form of alien hand syndrome has been noted in CBD, in which an individual’s hand displays an avoidance response to external stimuli. Additionally, sensory impairment, revealed through limb numbness or the sensation of prickling, may also concurrently arise with alien hand syndrome, as both symptoms are indicative of cortical dysfunction. Like most of the movement disorders, alien hand syndrome also presents asymmetrically in those diagnosed with CBD.[7]

Apraxia

Ideomotor apraxia (IMA), although clearly present in CBD, often manifests atypically due to the additional presence of bradykinesia and rigidity in those individuals exhibiting the disorders. The IMA symptom in CBD is characterized by the inability to repeat or mimic particular movements (whether significant or random) both with or without the implementation of objects. This form of IMA is present in the hands and arms, while IMA in the lower extremities may cause problems with walking. Those with CBD that exhibit IMA may appear to have trouble initiating walking, as the foot may appear to be fixed to floor. This can cause stumbling and difficulties in maintaining balance.[3] IMA is associated with deterioration in the premotor cortex, parietal association areas, connecting white matter tracts, thalamus, and basal ganglia. Some individuals with CBD exhibit limb-kinetic apraxia, which involves dysfunction of more fine motor movements often performed by the hands and fingers.[6]

Aphasia

Aphasia in CBD is revealed through the inability to speak or a difficulty in initiating spoken dialogue and falls under the non-fluent (as opposed to fluent or flowing) subtype of the disorder. This may be related to speech impairment such as dysarthria, and thus is not a true aphasia, as aphasia is related to a change in language function, such as difficulty retrieving words or putting words together to form meaningful sentences. The speech and/or language impairments in CBD result in disconnected speech patterns and the omission of words. Individuals with this symptom of CBD often lose the ability to speak as the disease progresses.[3]

Psychiatric and cognitive disorders

Psychiatric problems associated with CBD often present as a result of the debilitating symptoms of the disease. Prominent psychiatric and cognitive conditions cited in individuals with CBD include dementia, depression, and irritability, with dementia forming a key feature that sometimes leads to the misdiagnosis of CBD as another cognitive disorder such as Alzheimer's disease (AD). Frontotemporal dementia can be an early feature.[8]

Corticobasal syndrome

All of the disorders and dysfunctions associated with CBD can often be categorized into a class of symptoms that present with the disease of CBD. These symptoms that aid in clinical diagnosis are sometimes collectively referred to as corticobasal syndrome (CBS) or corticobasal degeneration syndrome (CBDS). Alzheimer's disease, Pick's disease, and progressive supranuclear palsy can display a corticobasal syndrome.[9][10] It has been suggested that the nomenclature of corticobasal degeneration only be used for naming the disease after it has received verification through postmortem analysis of the neuropathology.[4] CBS patients with greater temporoparietal degeneration are more likely to have AD pathology as opposed to frontotemporal lobar degeneration.[11]

Neuroimaging

The types of imaging techniques that are most prominently utilized when studying and/or diagnosing CBD are:

- magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)

- fluorodopa positron emission tomography (FDOPA PET)

Developments or improvements in imaging techniques provide the future possibility for definitive clinical diagnosis prior to death. However, despite their benefits, information learned from MRI and SPECT during the beginning of CBD progression tend to show no irregularities that would indicate the presence of such a neurodegenerative disease.[3] FDOPA PET is used to study the efficacy of the dopamine pathway.[12]

Despite the undoubted presence of cortical atrophy (as determined through MRI and SPECT) in individuals experiencing the symptoms of CBD, this is not an exclusive indicator for the disease. Thus, the utilization of this factor in the diagnosis of CBD should be used only in combination with other clinically present dysfunctions.[4]

MRI

MRI images are useful in displaying atrophied portions of neuroanatomical positions within the brain. As a result, it is especially effective in identifying regions within different areas of the brain that have been negatively affected due to the complications associated with CBD. To be specific, MRI of CBD typically shows posterior parietal and frontal cortical atrophy with unequal representation in corresponding sides. In addition, atrophy has been noted in the corpus callosum.[12]

Functional MRI (fMRI) has been used to evaluate the activation patterns in various regions of the brain of individuals affected with CBD. Upon the performance of simple finger motor tasks, subjects with CBD experienced lower levels of activity in the parietal cortex, sensorimotor cortex, and supplementary motor cortex than those individuals tested in a control group.[12]

SPECT

SPECT studies of individuals diagnosed with CBD involve perfusion analysis throughout the parts of the brain. SPECT evaluation through perfusion observation consists of monitoring blood release into different locations in tissue or organ regions, which, in the case of CBD, pertains to localized areas within the brain. Tissue can be characterized as experiencing overperfusion, underperfusion, hypoperfusion, or hyperperfusion. Overperfusion and underperfusion relate to a comparison with the overall perfusion levels within the entire body, whereas hypoperfusion and hyperperfusion are calculated in comparison to the blood flow requirements of the tissue in question. In general, the measurements taken for CBD using SPECT are referred to as regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF).[12]

In general, SPECT reveals hypoperfusion within both the posterior regions of the frontal and parietal lobes. As in images gathered through MRI, SPECT images indicated asymmetry in the presentation of abnormalities throughout the brain.[4] Additional studies have revealed the presence of perfusion anomalies in the thalamus, temporal cortex, basal ganglia, and pontocerebellar (from the pons to the cerebellum) locations within subjects’ brains.[12]

FDOPA PET

Research has suggested that the integrity of the dopamine system in the striatum has been damaged as an effect of CBD. Current studies employing the use of FDOPA PET scanning (FDOPA PET) as a possible method for identifying CBD have focused on analyzing the efficiency of neurons in the striatum that utilize the neurotransmitter dopamine. These studies have concluded that, in general, dopamine uptake was diminished in the caudate and the putamen. This characteristic also has the potential to be useful in distinguishing CBD from the similar PD, as individuals having been diagnosed with PD were more likely to have a lower uptake of dopamine than in individuals with CBD.[12]

Other clinical tests or procedures that monitor the presence of dopamine within the brain (β-CIT SPECT and IBZM SPECT) have shown similar findings. β-CIT serves as an indicator for presynaptic dopaminergic neurons, whereas IBZM is a tracer that shows an affinity for the postsynaptic neurons of the same type. Despite agreement with other imaging studies, these two SPECT methods suffer some scrutiny due to better accuracy in other imaging methods. However, β-CIT SPECT has proven to be helpful in distinguishing CBD from PSP and multiple system atrophy (MSA).[12]

Histological and molecular features

Neuropathological findings associated with CBD include the presence of astrocytic abnormalities within the brain and improper accumulation of the protein tau (referred to as tauopathy).[13]

Astroglial inclusions

Postmortem histological examination of the brains of individuals diagnosed with CBD reveal unique characteristics involving the astrocytes in localized regions.[14] The typical procedure used in the identification of these astroglial inclusions is the Gallyas-Braak staining method. This process involves exposing tissue samples to a silver staining material which marks for abnormalities in the tau protein and astroglial inclusions.[15] Astroglial inclusions in CBD are identified as astrocytic plaques, which present as annularly displays of blurry outgrowths from the astrocyte. A recent study indicated that CBD produces a high density of astrocytic plaques in the anterior portion of the frontal lobe and in the premotor area of the cerebral cortex.[16]

Tauopathy

The protein tau is an important microtubule-associated protein (MAP), and is typically found in neuronal axons. However, malfunctioning of the development of the protein can result in unnatural, high-level expression in astrocytes and glial cells. As a consequence, this is often responsible for the astrocytic plaques prominently noted in histological CBD examinations. Although they are understood to play a significant role in neurodegenerative diseases such as CBD, their precise effect remains a mystery.[15]

Diagnosis

Clinical vs. postmortem

One of the most significant problems associated with CBD is the inability to perform a definitive diagnosis while an individual exhibiting the symptoms associated with CBD is still alive. A clinical diagnosis of CBD is performed based upon the specified diagnostic criteria, which focus mainly on the symptoms correlated with the disease. However, this often results in complications as these symptoms often overlap with numerous other neurodegenerative diseases.[17] Frequently, a differential diagnosis for CBD is performed, in which other diseases are eliminated based on specific symptoms that do not overlap. However, some of the symptoms of CBD used in this process are rare to the disease, and thus the differential diagnosis cannot always be used.[3]

Postmortem diagnosis provides the only true indication of the presence of CBD. Most of these diagnoses utilize the Gallyas-Braak staining method, which is effective in identifying the presence of astroglial inclusions and coincidental tauopathy.

Overlap with other diseases

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is frequently the disease most often confused with CBD. Both PSP and CBD result in similar symptoms, and both display tauopathies upon histological inspection.[18] However, it has been noted that tauopathy in PSP results in tuft-shaped astrocytes in contrast with the doughnut-shaped astrocytic plaques found as a result of CBD.[16]

Individuals diagnosed with PD often exhibit similar movement dysfunction as those diagnosed with CBD, which adds complexity to its diagnosis. Some other neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer's disease (AD), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) also show commonalities with CBD.[3][19][20] FTDs have also been known to evolve into corticobasal syndrome.[21]

Treatment

Because the exact cause of CBD is unknown, there exists no formal treatment for the disease. Instead, treatments focus on minimizing the appearance or effect of the symptoms resulting from CBD. The most easily treatable symptom of CBD is parkinsonism, and the most common form of treatment for this symptom is the application of dopaminergic drugs. However, in general only moderate improvement is seen and the relief from the symptom is not long-lasting. In addition, palliative therapies, including the implementation of wheelchairs, speech therapy, and feeding techniques, are often used to alleviate many of the symptoms that show no improvement with drug administration.[22]

Occurrence and epidemiology

Clinical presentation of CBD usually does not occur until age 60, with the earliest recorded diagnosis and subsequent postmortem verification being age 28.[12] Although men and women present with the disease, some analysis has shown a predominant appearance of CBD in women. Current calculations suggest that the prevalence of CBD is approximately 4.9 to 7.3 per 100,000 people. The prognosis for an individual diagnosed with CBD is death within approximately eight years, although some patients have been diagnosed over 13 years ago (1999) and are still in relatively good standing, but with serious debilitation such as dysphagia, and overall limb rigidity. The partial (or total) use of a feeding tube may be necessary and will help prevent aspiration pneumonia, primary cause of death in CBD. Incontinence is common, as patients often can't express their need to go, due to eventual loss of speech. Therefore, proper hygiene is mandatory to prevent urinary tract infections.[3]

Background and history

CBD was first identified by Rebeiz and his associates in 1968, as they observed three individuals who exhibited characteristic symptoms of the unique and previously unknown disorder. They initially referred to the neurodegenerative disease as “corticodentatonigral degeneration with neuronal achromasia,” after which various other names were used, including “corticonigral degeneration with nuclear achromasia” and “cortical basal ganglionic degeneration.”[2] Although the underlying cause of CBD is unknown, the disease occurs as a result of damage to the basal ganglia, specifically marked by neuronal degeneration or depigmentation (loss of melanin in a neuron) in the substantia nigra.[18] Additional distinguishing neurological features of those diagnosed with CBD consist of asymmetric atrophy of the frontal and parietal cortical regions of the brain.[2] Postmortem studies of patients diagnosed with CBD indicate that histological attributes often involve ballooning of neurons, gliosis, and tauopathy.[18] Much of the pioneering advancements and research performed on CBD has been completed within the past decade or so, due to the relatively recent formal recognition of the disease.

See also

References

- ↑ "Corticobasal Degeneration Information Page: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)". Retrieved 2009-03-20.

- 1 2 3 4 Wadia PM, Lang AE (2007). "The many faces of corticobasal degeneration". Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 13: S336–S40. doi:10.1016/s1353-8020(08)70027-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Mahapatra RK, Edwards MJ, Schott JM, Bhatia KP (2004). "Corticobasal degeneration". Lancet Neurology. 3: 736–43. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(04)00936-6.

- 1 2 3 4 Koyama M, Yagishita A, Nakata Y, Hayashi M, Bandoh M, Mizutani T (2007). "Imaging of corticobasal degeneration syndrome". Neuroradiology. 49: 905–12. doi:10.1007/s00234-007-0265-6.

- ↑ Rana AQ, Ansari H, Siddiqui I (2012). "The relationship between arm dystonia in corticobasal degeneration and handedness". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 19: 1134–6. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2011.10.012.

- 1 2 Belfor N, Amici S, Boxer AL, Kramer JH, Gorno-Tempini ML, et al. (2006). "Clinical and neuropsychological features of corticobasal degeneration". Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 127: 203–7. doi:10.1016/j.mad.2005.09.013.

- ↑ FitzGerald DB, Drago V, Jeong Y, Chang YL, White KD, Heilman KM (2007). "Asymmetrical alien hands in corticobasal degeneration". Movement Disorders. 22: 581–4. doi:10.1002/mds.21337.

- ↑ Suzee E. Lee, MD,1 Gil D. Rabinovici, MD,1 Mary Catherine Mayo,1 Stephen M. Wilson, PhD,1,2 William W. Seeley, MD,1 Stephen J. DeArmond, MD, PhD,3 Eric J. Huang, MD, PhD,3 John Q. Trojanowski, MD, PhD,4 Matthew E. Growdon,1 Jung Y. Jang,1 Manu Sidhu,1 Tricia M. See, ScM,1 Anna M. Karydas,1 Maria-Luisa Gorno-Tempini, MD, PhD,1 Adam L. Boxer, MD, PhD,1 Michael W. Weiner, MD,1 Michael D. Geschwind, MD, PhD,1 Katherine P. Rankin, PhD,1 and Bruce L. Miller, MD1 (August 2011). "Clinicopathological correlations in corticobasal degeneration". Ann. Neurol. 70 (2): 327–340. doi:10.1002/ana.22424. PMC 3154081

. PMID 21823158.

. PMID 21823158. - ↑ Hassan A1, Whitwell JL, Josephs KA. (Nov 2011). "The corticobasal syndrome-Alzheimer's disease conundrum". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 11: 1569–78. doi:10.1586/ern.11.153. PMID 22014136.

- ↑ Alladi S1, Xuereb J, Bak T, Nestor P, Knibb J, Patterson K, Hodges JR. (October 2007). "Focal cortical presentations of Alzheimer's disease". Brain. 130 (10): 2636–45. doi:10.1093/brain/awm213. PMID 17898010.

- ↑ Sharon J Sha,corresponding author Pia M Ghosh, Suzee E Lee, Chiara Corbetta-Rastelli, Willian J Jagust, John Kornak, Katherine P Rankin, Lea T Grinberg, Harry V Vinters, Mario F Mendez, Dennis W Dickson, William W Seeley, Marilu Gorno-Tempini, Joel Kramer, Bruce L Miller, Adam L Boxer, and Gil D Rabinovici (March 2015). "Predicting amyloid status in corticobasal syndrome using modified clinical criteria, magnetic resonance imaging and fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography". Alzheimers Res Ther. 7 (1): 8. doi:10.1186/s13195-014-0093-y. PMC 4346122

. PMID 25733984.

. PMID 25733984. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Seritan AL, Mendez MF, Silverman DH, Hurley RA, Taber KH (2004). "Functional imaging as a window to dementia: Corticobasal degeneration". Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 16: 393–9. doi:10.1176/jnp.16.4.393.

- ↑ Rizzo G, Martinelli P, Manners D, et al. (October 2008). "Diffusion-weighted brain imaging study of patients with clinical diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy and Parkinson's disease". Brain. 131 (Pt 10): 2690–700. doi:10.1093/brain/awn195. PMID 18819991.

- ↑ Zhu MW1, Wang LN, Li XH, Gui QP. (April 2004). "Glial abnormalities in progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration". Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 33 (2): 125–9. PMID 15132848.

- 1 2 Komori T (1999). "Tau-positive glial inclusions in progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration and Pick's disease". Brain Pathology. 9: 663–79. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00549.x.

- 1 2 Hattori M, Hashizume Y, Yoshida M, Iwasaki Y, Hishikawa N, et al. (2003). "Distribution of astrocytic plaques in the corticobasal degeneration brain and comparison with tuft-shaped astrocytes in the progressive supranuclear palsy brain". Acta Neuropathologica. 106: 143–9. doi:10.1007/s00401-003-0711-4. PMID 12732936.

- ↑ Litvan I, Agid Y, Goetz C, Jankovic J, Wenning GK, Brandel JP, Lai EC, Verny M, Ray-Chaudhuri K, McKee A, Jellinger K, Pearce RK, Bartko JJ. (Jan 1997). "Accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration: a clinicopathologic study" (PDF). Neurology. 48 (1): 119–25. doi:10.1212/wnl.48.1.119. PMID 9008506.

- 1 2 3 Scaravilli T, Tolosa E, Ferrer I (2005). "Progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration: Lumping versus splitting". Movement Disorders. 20: S21–S8. doi:10.1002/mds.20536.

- ↑ Jendroska K, Rossor MN, Mathias CJ, Daniel SE. (Jan 1995). "Morphological overlap between corticobasal degeneration and Pick's disease: a clinicopathological report.". Mov Disord. 10 (1): 111–4. doi:10.1002/mds.870100118. PMID 7885345.

- ↑ Suzee E. Lee, MD,1 Gil D. Rabinovici, MD,1 Mary Catherine Mayo,1 Stephen M. Wilson, PhD,1,2 William W. Seeley, MD,1 Stephen J. DeArmond, MD, PhD,3 Eric J. Huang, MD, PhD,3 John Q. Trojanowski, MD, PhD,4 Matthew E. Growdon,1 Jung Y. Jang,1 Manu Sidhu,1 Tricia M. See, ScM,1 Anna M. Karydas,1 Maria-Luisa Gorno-Tempini, MD, PhD,1 Adam L. Boxer, MD, PhD,1 Michael W. Weiner, MD,1 Michael D. Geschwind, MD, PhD,1 Katherine P. Rankin, PhD,1 and Bruce L. Miller, MD1 (August 2011). "Clinicopathological correlations in corticobasal degeneration". Ann Neurol. 70 (2): 327–340. doi:10.1002/ana.22424. PMC 3154081

.

. - ↑ Gorno-Tempini ML, Murray RC, Rankin KP, Weiner MW, Miller BL. (Dec 2004). "Clinical, cognitive and anatomical evolution from nonfluent progressive aphasia to corticobasal syndrome: a case report.". Neurocase: case studies in neuropsychology, neuropsychiatry, and behavioral neurology. 10 (6): 426–36. doi:10.1080/13554790490894011. PMC 2365737

. PMID 15788282.

. PMID 15788282. - ↑ Lang AE (2005). "Treatment of progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration". Movement Disorders. 20: S83–S91. doi:10.1002/mds.20545.

External links

- Foundation for PSP | CBD and Related Brain Diseases

- CBD Solutions

- The Association for Frontotemporal Dementias

- The PSP Association (UK body for PSP and CBD)

- Mayo Clinic

- UCSF Memory and Aging Center