Cosmogony

Cosmogony (or cosmogeny) is any model concerning the origin of either the cosmos or universe.[1][2] Developing a complete theoretical model has implications in both the philosophy of science and epistemology.

Etymology

The word comes from the Koine Greek κοσμογονία (from κόσμος "cosmos, the world") and the root of γί(γ)νομαι / γέγονα ("come into a new state of being").[3] In astronomy, cosmogony refers to the study of the origin of particular astrophysical objects or systems, and is most commonly used in reference to the origin of the universe, the solar system, or the earth-moon system.[1][2]

Overview

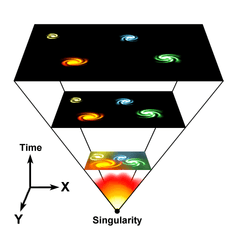

The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological model of the early development of the universe.[4] The most commonly held view is that the universe was once a gravitational singularity, which expanded extremely rapidly from its hot and dense state. However, while this expansion is well-modeled by the Big Bang theory, the origins of the singularity remain as one of the unsolved problems in physics.

Cosmologist and science communicator Sean M. Carroll explains two competing types of explanations for the origins of the singularity which is the main disagreement between the scientists who study cosmogony and centers on the question of whether time existed "before" the emergence of our universe or not. One cosmogonical view sees time as fundamental and even eternal: The universe could have contained the singularity because the universe evolved or changed from a prior state (the prior state was "empty space", or maybe a state that could not be called "space" at all). The other view, held by proponents like Stephen Hawking, says that there was no change through time because "time" itself emerged along with this universe (in other words, there can be no "prior" to the universe).[5] Thus, it remains unclear what combination of "stuff", space, or time emerged with the singularity and this universe.[5]

One problem in cosmogony is that there is currently no theoretical model that explains the earliest moments of the universe's existence (during the Planck time) because of a lack of a testable theory of quantum gravity. Researchers in string theory and its extensions (for example, M theory), and of loop quantum cosmology, have nevertheless proposed solutions of the type just discussed.

Another issue facing the field of particle physics is a need for more expensive and technologically advanced particle accelerators to test proposed theories (for example, that the universe was caused by colliding membranes).

Compared with cosmology

Cosmology is the study of the structure and changes in the present universe, while the scientific field of cosmogony is concerned with the origin of the universe. Observations about our present universe may not only allow predictions to be made about the future, but they also provide clues to events that happened long ago when ... the cosmos began. So the work of cosmologists and cosmogonists overlaps.

Cosmogony can be distinguished from cosmology, which studies the universe at large and throughout its existence, and which technically does not inquire directly into the source of its origins. There is some ambiguity between the two terms. For example, the cosmological argument from theology regarding the existence of God is technically an appeal to cosmogonical rather than cosmological ideas. In practice, there is a scientific distinction between cosmological and cosmogonical ideas. Physical cosmology is the science that attempts to explain all observations relevant to the development and characteristics of the universe as a whole. Questions regarding why the universe behaves in such a way have been described by physicists and cosmologists as being extra-scientific (i.e., metaphysical), though speculations are made from a variety of perspectives that include extrapolation of scientific theories to untested regimes (i.e., at Planck scales), and philosophical or religious ideas.

Theoretical scenarios

Cosmogonists have only tentative theories for the early stages of the universe and its beginning. As of 2011, no accelerator experiments probe energies of sufficient magnitude to provide any experimental insight into the behavior of matter at the energy levels that prevailed shortly after the Big Bang. Furthermore, since astronomical observations imply a singularity at the origin of the universe, experiments at any given high energy level will always be dwarfed by the infinite energy level predicted by Big Bang Theory. Therefore, significant technological and conceptual advances would be needed to propose a scientific test for cosmogonical theories.

Proposed theoretical scenarios differ radically, and include string theory and M-theory, the Hartle–Hawking initial state, string landscape, brane inflation, the Big Bang, and the ekpyrotic universe. Some of these models are mutually compatible, whereas others are not.

See also

References

- 1 2 Ridpath, Ian (2012). A Dictionary of Astronomy. Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 Woolfson, M.M. (1979). "Cosmogony Today". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 20 (2): 97–114. Bibcode:1979QJRAS..20...97W.

- ↑ Staff. "γίγνομαι - come into a new state of being". Tufts University. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ↑ Wollack, Edward J. (10 December 2010). "Cosmology: The Study of the Universe". Universe 101: Big Bang Theory. NASA. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- 1 2 3 "A Universe from Nothing?, by Sean Carroll, Discover Magazine Blogs, 28 April 2012.". Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ↑ "Cosmic Chemistry: Cosmogony : Teacher Text : Background Information" (PDF). Genesismission.jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved 14 January 2015.