Dirty Harry

| Dirty Harry | |

|---|---|

|

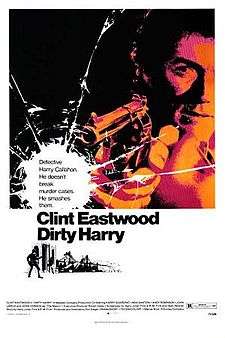

Theatrical release poster by Bill Gold | |

| Directed by | Don Siegel |

| Produced by |

Don Siegel Robert Daley |

| Screenplay by |

Harry Julian Fink R.M. Fink Dean Riesner John Milius (uncredited) |

| Story by |

Harry Julian Fink R.M. Fink Jo Heims Uncredited : Terrence Malick |

| Starring |

Clint Eastwood Andy Robinson Harry Guardino Reni Santoni John Vernon |

| Music by | Lalo Schifrin |

| Cinematography | Bruce Surtees |

| Edited by | Carl Pingitore |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 102 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $4 million |

| Box office | $36 million[1] |

Dirty Harry is a 1971 American action thriller film produced and directed by Don Siegel, the first in the Dirty Harry series. Clint Eastwood plays the title role, in his first outing as San Francisco Police Department (SFPD) Inspector "Dirty" Harry Callahan. The film drew upon the actual case of the Zodiac Killer as the Callahan character seeks out a similar vicious psychopath.[2]

Dirty Harry was a critical and commercial success and set the style for a whole genre of police films. It was followed by four sequels: Magnum Force in 1973, The Enforcer in 1976, Sudden Impact in 1983 (directed by Eastwood himself) and The Dead Pool in 1988.

In 2012, the film was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for being "culturally, historically, and aesthetically significant."[3]

Plot

A psychopathic serial killer calling himself "Scorpio" (Andy Robinson) shoots a young woman in a San Francisco swimming pool from a nearby rooftop. SFPD Inspector Harry Callahan (Clint Eastwood) finds a blackmail message demanding the city pay him $100,000 whilst also promising that for each day his demand is refused he will commit a murder; his next victim will be "a Catholic priest or a nigger." The chief of police and the mayor (John Vernon) assign the inspector to the case, despite his reputation for violent solutions.

While in a local diner, Callahan observes a bank robbery in progress. He goes outside and kills two of the robbers while wounding a third. Callahan then challenges him:

I know what you’re thinking: 'Did he fire six shots or only five?' Well, to tell you the truth, in all this excitement, I’ve lost track myself. But being this is a .44 Magnum, the most powerful handgun in the world, and would blow your head clean off, you’ve got to ask yourself one question: 'Do I feel lucky?' Well, do you, punk?

After the robber surrenders, he tells Callahan that he must know if the gun was still loaded ("I gots to know...") . Callahan pulls the trigger, with the weapon pointed directly at the robber, and laughs, as it is revealed to be empty.

Scorpio targets a gay black male, but is interrupted by a police helicopter and escapes. Later that night, Callahan and his rookie partner, Chico Gonzalez (Reni Santoni) pursue a likely suspect, but it turns out to be a false alarm. Following that, Callahan successfully halts a suicide attempt, after which he reveals that the origin of his nickname comes from the fact that he is given every dirty job to do.

When Scorpio kills a young black boy from another rooftop, the police believe the killer will next pursue a Catholic priest. Callahan and Gonzalez, wait for Scorpio near a Catholic church, where a rooftop-to-rooftop shootout ensues, with Callahan attempting to snipe Scorpio with a rifle while Scorpio returns fire with a submachine gun. Scorpio escapes, killing a police officer disguised as a priest.

Scorpio then demands $200,000 ($1.2 million today) for a teenage girl he has kidnapped, threatening to let her suffocate otherwise. The mayor decides to pay and tells Callahan to deliver the money with no tricks, but the inspector wears a covert listening device, brings a switchblade, and has his partner follow him. As Scorpio sends Callahan to various payphones throughout the city to make sure he is alone, the chase ends at Mount Davidson. Scorpio brutally beats Callahan and tells him he's going to kill him and let the girl die anyway; Gonzalez comes to his partner's rescue but is wounded. Callahan stabs Scorpio in the leg, but the killer escapes without the money.

The doctor who has treated Scorpio's wound phones the police and tells Callahan and his new partner that he has seen Scorpio in Kezar Stadium. The officers break in and Callahan shoots Scorpio in his wounded leg. When Scorpio refuses to reveal the location of the girl and demands his rights, Callahan makes him confess by standing on the wounded leg, but the police are too late to save her.

Because Callahan searched Scorpio's home without a warrant and improperly seized his rifle for evidence, the District Attorney (Josef Sommer) has no choice but to let Scorpio go. Outraged, Callahan warns that Scorpio will kill again and follows him on his own time. To thwart Callahan, Scorpio pays to have himself beaten by a thug, then claims the inspector is responsible. Despite Callahan's protests, he is ordered to stop following Scorpio.

After stealing a gun from a liquor store owner, Scorpio kidnaps a school busload of children and demands a $200,000 ransom and a plane to leave the country. The mayor again insists on paying but Callahan angrily refuses when asked to deliver the ransom. Instead he locates the bus and jumps onto the top from a bridge. The bus crashes into a dirt embankment and Scorpio flees into a nearby quarry, where he has a running gun battle with Callahan. Finally Scorpio spots a young boy sitting near a pond and grabs him as a hostage.

The inspector feigns surrender, but fires, wounding Scorpio in his left shoulder. The boy runs away and Callahan stands over Scorpio, gun drawn, reprising his "Do you feel lucky, punk?" speech. Scorpio lunges for his gun and Callahan shoots him instantly, causing him to fall into the water. As Callahan watches the dead body floating, he takes out his inspector's badge and hurls it into the water before walking away.

Cast

- Clint Eastwood as SFPD Homicide Inspector Harry Callahan

- Andy Robinson as Scorpio

- Harry Guardino as SFPD Homicide Lt. Al Bressler

- Reni Santoni as SFPD Homicide Inspector Chico Gonzalez

- John Vernon as The Mayor of San Francisco

- John Larch as Chief of Police

- John Mitchum as SFPD Homicide Inspector Frank "Fatso" DiGiorgio

- Woodrow Parfrey as Jaffe

- Josef Sommer as District Attorney William T. Rothko

- Albert Popwell as Bank robber

- Lyn Edgington as Norma Gonzalez

- Ruth Kobart as Marcella Platt (school bus driver)

- Lois Foraker as Hot Mary

- William Paterson as Bannerman

- Craig Kelly as SFPD Sgt. Reineke

Production

Development

The script, titled Dead Right, was originally written by Harry Julian and Rita M. Fink, a story about a hard-edged New York City police inspector, Harry Callahan, determined to stop Travis, a serial killer, by any means at his disposal.[4][5] The original draft ended with a police sniper, instead of Callahan, shooting Scorpio. Another earlier version of the story was set in Seattle, Washington. Four more drafts of the script were written.

Although Dirty Harry is arguably Clint Eastwood's signature role, he was not a top contender for the part. The role of Harry Callahan was offered to John Wayne and Frank Sinatra,[6] and later to Robert Mitchum, Steve McQueen, and Burt Lancaster.[4] In his 1980 interview with Playboy, George C. Scott claimed that he was initially offered the role, but the script's violent nature led him to turn it down. When producer Jennings Lang initially could not find an actor to take the role of Callahan, he sold the film rights to ABC Television. Although ABC wanted to turn it into a television film, the amount of violence in the script was deemed too excessive for television, so the rights were sold to Warner Bros.[7]

Warner Bros. purchased the script with a view to casting Frank Sinatra in the lead. Sinatra was 55 at the time and since the character of Harry Callahan was originally written as a man in his mid-to-late 50s (and Eastwood was then only 41), Sinatra fit the character profile. Initially, Warner Bros. wanted either Sydney Pollack or Irvin Kershner to direct.[5] Kershner was eventually hired when Sinatra was attached to the title role, but when Sinatra eventually left the film, so did Kershner.[8]

John Milius was asked to work on the script when Sinatra was attached, along with Kershner as director. Milius claimed he was requested to write the screenplay for Sinatra in three weeks.[9] Terrence Malick wrote a draft of the film dated November 1970 (John Milius and Harry Julian Fink are also named as co-writers) in which the shooter (also named Travis) was a vigilante who killed wealthy criminals who had escaped justice.[10] Malick's ideas formed the basis for the sequel, Magnum Force, though with a group of vigilante motorcycle cops instead of a single shooter.

Details about the film were first released in film industry trade papers in April, September and November 1970, with Frank Sinatra attached as Harry Callahan and Irvin Kershner listed as director and producer, with Arthur Jacobson acting as associate producer.[4]

After Sinatra left the project, the producers started to consider younger actors for the role. Burt Lancaster turned down the lead role because he strongly disagreed with the violent, end-justifies-the-means moral of the story. He believed the role and plot contradicted his belief in collective responsibility for criminal and social justice and the protection of individual rights.[11] Marlon Brando was considered for the role, but was never formally approached. Both Steve McQueen and Paul Newman turned down the role.[4] McQueen refused to make another "cop movie" after Bullitt (1968). He would also turn down the lead in The French Connection the same year, giving the same reason. Believing the character was too "right-wing" for him, Newman suggested that the film would be a good vehicle for Eastwood.[8]

The screenplay was initially brought to Eastwood’s attention around 1969 by Jennings Lang. Warner Bros offered him the part while still in post-production for his directorial debut film Play Misty for Me. By December 17, 1970, a Warner Brothers studio press release announced that Clint Eastwood would star in as well as produce the film through his company, Malpaso.

Eastwood was given a number of scripts, but he ultimately reverted to the original as the best vehicle for him.[12] In a 2009 MTV interview, Eastwood said "So I said, 'I'll do it,' but since they had initially talked to me, there had been all these rewrites. I said, 'I'm only interested in the original script'." Looking back on the 1971 Don Siegel film, he remembered "[The rewrites had changed] everything. They had Marine snipers coming on in the end. And I said, 'No. This is losing the point of the whole story, of the guy chasing the killer down. It's becoming an extravaganza that's losing its character.' They said, 'OK, do what you want.' So, we went and made it."[13]

Eastwood also agreed to star in the film only on condition that Don Siegel direct. Siegel was under contract to Universal at the time, and Eastwood personally went to the studio heads to ask them to "loan" Siegel to Warner. The two had just completed the movie The Beguiled (1971).

Scorpio was loosely based on the real-life Zodiac Killer, an unidentified serial killer who had committed five murders in the San Francisco Bay Area several years earlier.[14] Elements of Gary Stephen Krist were also worked into the characterization, as Scorpio, like Krist, kidnaps a young girl and buries her alive while demanding ransom. In a later novelization of the film, Scorpio was referred to as "Charles Davis", a former mental patient from Springfield, Massachusetts who murdered his grandparents as a teenager.[15] There are significant differences between the book and the film. Among the differences are: Scorpio's point of view — in the book he uses astrology to make decisions (including being inspired to abduct Ann Mary Deacon); Harry working on a murder case involving a mugger before he is assigned to Scorpio; the omission of the suicide jumper; and Harry throwing away his badge at the end. Audie Murphy was initially considered to play Scorpio, but he died in a plane crash before his decision on the offer could be made.[16] When Kershner and Sinatra were still attached to the project, James Caan was under consideration for the role of Scorpio.[16] The part eventually went to a relatively unknown actor, Andy Robinson. Eastwood had seen Robinson in a play called Subject to Fits and recommended him for the role of Scorpio; his unkempt appearance fit the bill for a psychologically unbalanced hippie.[17] Siegel told Robinson that he cast him in the role of the Scorpio killer because he wanted someone "with a face like a choirboy." Robinson's portrayal was so memorable that after the film was released he was reported to have received several death threats and was forced to get an unlisted telephone number. In real life, Robinson is a pacifist who deplores the use of firearms. Early in principal photography on the film, Robinson would reportedly flinch in discomfort every time he was required to use a gun. As a result, Siegel was forced to halt production briefly and sent Robinson for brief training in order to learn how to fire a gun convincingly.[18]

Milius says his main contribution to the film was "a lot of guns. And the attitude of Dirty Harry, being a cop who was ruthless. I think it's fairly obvious if you look at the rest of my work what parts are mine. The cop being the same as the killer except he has a badge. And being lonely... I wanted it to be like Stray Dog; I was thinking in terms of Kurosawa's detective films."[19] He added:

In my script version, there's just more outrageous Milius crap where I had the killer in the bus with a flamethrower. I tried to make the guy as outrageous as possible. I had him get a police photographer to take a picture of him with all the kids lined up at the school - he kidnaps them at the school, actually - and they showed the picture to the other police after he's made his demands; he wants a 747 to take him away to a country where he'll be free of police harassment [Milius laughs uproariously], terrible things like this. And the children all end up like a graduation picture, and the teacher is saying, "What is that object under Andy Robinson?" and a cop says, "That's a claymore mine." Teacher asks, "What's a claymore mine?" And we hear the voice of Harry say, "If he sets it off, they're all spaghetti." Chief says, "That's enough, Harry." Everybody said, "That's too much, John; we can't have Milius doing this kind of stuff." I wanted the guy to be just totally outrageous all the time, and he is. I think Siegel restrained it enough.[19]

Director John Milius owns one of the actual Model 29s used in principal photography in Dirty Harry and Magnum Force.[20] As of March 2012 it is on loan to the National Firearms Museum in Fairfax, Virginia, and is in the Hollywood Guns display in the William B. Ruger Gallery.[21]

Principal photography

Glenn Wright, Eastwood's costume designer since Rawhide, was responsible for creating Callahan's distinctive old-fashioned brown and yellow checked jacket to emphasize his strong values in pursuing crime.[17] Filming for Dirty Harry began in April 1971 and involved some risky stunts, with much footage shot at night and filming the city of San Francisco aerially, a technique for which the film series is renowned.[17] Eastwood performed the stunt in which he jumps onto the roof of the hijacked school bus from a bridge, without a stunt double. His face is clearly visible throughout the shot. Eastwood also directed the suicide-jumper scene.

The line, "My, that's a big one," spoken by Scorpio when Callahan removes his gun, was an ad-lib by Robinson. The crew broke into laughter as a result of the double entendre and the scene had to be re-shot, but the line stayed.

The final scene, in which Callahan throws his badge into the water, is a homage to a similar scene from 1952's High Noon.[22] Eastwood initially did not want to toss the badge, believing it indicated that Callahan was quitting the police department. Siegel argued that tossing the badge was instead Callahan's indication of casting away the inefficiency of the police force's rules and bureaucracy.[22] Although Eastwood was able to convince Siegel not to have Callahan toss the badge, when the scene was filmed, Eastwood changed his mind and went with Siegel's preferred ending.[22]

Filming locations

One evening Eastwood and Siegel had been watching the San Francisco 49ers in Kezar Stadium in the last game of the season and thought the eerie Greek amphitheater-like setting would be an excellent location for shooting one of the scenes where Callahan encounters Scorpio.[23]

- 555 California Street, The Bank of America Building

- California Hall, 625 Polk Street (formerly the California Culinary Academy)

- San Francisco City Hall, 1 Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett Place

- Hall of Justice – 850 Bryant Street

- Forest Hill Station

- Holiday Inn Chinatown, 750 Kearny Street - rooftop swimming pool 37°47′42.7″N 122°24′15.7″W / 37.795194°N 122.404361°W in the opening scenes. It is now the Hilton - Chinatown.[24]

- Kezar Stadium – Frederick Street, Golden Gate Park

- Dolores Park, Mission District

- Mount Davidson

- Sts. Peter and Paul Church, north of Washington Square, 666 Filbert Street[25]

- Washington Square, North Beach[26]

- Krausgrill Place, northeast of Washington Square[27]

- Medau Place, northeast of Washington Square[28]

- Jasper Alley, east of Washington Square[29]

- Big Al's strip club, 556 Broadway

- Roaring 20's strip club, 552 Broadway

- North Beach, San Francisco

- Hutchinson's Rock Quarry[30][31] — scene of Callahan and Scorpio's showdown, later filled in and redeveloped as Larkspur Landing Shopping Center and Larkspur Shores Apartments,[32] north of the Larkspur Ferry Terminal[33][34]

- Greenbrae, California

- Mill Valley, California

In Los Angeles County, California

- Universal Studios Hollywood — San Francisco Street (diner / bank robbery sequence)

Music

The soundtrack for Dirty Harry was created by composer Lalo Schifrin, who created the iconic music for both the theme of Mission: Impossible and the Bullitt soundtrack, and who had previously collaborated with director Don Siegel in the production of Coogan's Bluff and The Beguiled, both also starring Clint Eastwood. Schifrin fused a wide variety of influences, including classical music, jazz and psychedelic rock, along with Edda Dell'Orso-style vocals, into a score that "could best be described as acid jazz some 25 years before that genre began." According to one reviewer, the Dirty Harry soundtrack's influence "is paramount, heard daily in movies, on television, and in modern jazz and rock music."[35][36]

Release

Critical reception

The film caused controversy when it was released, sparking debate over issues ranging from police brutality to victims' rights and the nature of law enforcement. Feminists in particular were outraged by the film and at the 44th Academy Awards protested outside the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, holding up banners which read messages such as "Dirty Harry is a Rotten Pig".[37]

Jay Cocks of Time praised Eastwood's performance as Dirty Harry, describing him as "giving his best performance so far, tense, tough, full of implicit identification with his character".[38] Neal Gabler also praised Eastwood's performance in the film: "There's an incredible pleasure in watching Clint Eastwood do what he does, and he does it so well."[39] Film critic Roger Ebert, while praising the film's technical merits, denounced the film for its "fascist moral position."[40] A section of the Philippine police force ordered a print of the film for use as a training film.[41][42]

Since its release, the film's critical reputation has grown in stature. Dirty Harry was selected by in 2008 by Empire magazine as one of The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time.[43] It was placed similarly on The Best 1000 Movies Ever Made list by The New York Times.[44] In January 2010 Total Film included the film on its list of The 100 Greatest Movies of All Time.[45] TV Guide and Vanity Fair also included the film on their lists of the 50 best movies.[46][47]

A generation later, Dirty Harry is now regarded as one of the best films of 1971.[48][49][50] Based mainly on reviews from the 2000s, the film holds a 95% approval rating on the review aggregate website Rotten Tomatoes.[51] It was nominated at the Edgar Allan Poe Awards for Best Motion Picture.[52]

In 2014, Time Out polled several film critics, directors, actors and stunt actors to list their top action films.[53] Dirty Harry was listed at 78th place in this list.[54]

John Milius later said he loved the film. "I think it's a great film, one of the few recent great films, more important than The Godfather. It's larger than the sum of its parts; I don't think it's so brilliantly written or so brilliantly acted. Siegel can take more credit than anyone for it."[19]

Box office performance

The benefit world premiere of Dirty Harry was held at Loews' Market Street Cinema, 1077 Market Street (San Francisco),[55] on December 22, 1971.[56][57] The film was the fourth-highest-grossing film of 1971, earning an approximate total of $36 million in its U.S. theatrical release,[1] making it a major financial success in comparison with its modest $4 million budget.[58]

Home media

Warner Home Video owns rights to the Dirty Harry series. The studio first released the film to VHS and Betamax in 1979. Dirty Harry (1971) has been remastered for DVD three times — in 1998, 2001 and 2008. It has been repurposed for several DVD box sets. Dirty Harry made its high-definition debut with the 2008 Blu-ray Disc. The commentator on the 2008 DVD is Clint Eastwood biographer Richard Schickel.[59] The film, along with its sequels, has been released in High Definition, on various Digital distribution services, including the iTunes Store.[60]

Legacy

Dirty Harry received recognition from the American Film Institute. The film was ranked #41 on 100 Years...100 Thrills, a list of America's most heart-pounding movies.[61] Harry Callahan was selected as the 17th greatest movie hero on 100 Years ... 100 Heroes and Villains.[62] The movie's famous quote "You've got to ask yourself one question: 'Do I feel lucky?' Well, do ya, punk?" was ranked 51st on 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes.[63] Dirty Harry was also on the ballot for several other AFI's 100 series lists including 100 Years... 100 Movies,[64] 100 Years ... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition),[65] and 100 Years of Film Scores.[66]

Real-life copycat crime and killers

The film supposedly inspired a real-life crime, the Faraday School kidnapping.[67] In October 1972, soon after the release of the movie in Australia, two armed men (one of whom coincidentally had the last name 'Eastwood') kidnapped a teacher and six school children in Victoria. They demanded a $1 million ransom. The state government agreed to pay, but the children managed to escape and the kidnappers were subsequently jailed.[68]

In September 1981 a case occurred in Germany, under circumstances quite similar to the Barbara Jane Mackle case: A ten-year-old girl, Ursula Hermann, was buried alive in a box fitted with ventilation, lighting and sanitary systems to be held for ransom. The girl suffocated in her prison within 48 hours of her abduction because autumn leaves had clogged up the ventilation duct. Twenty-seven years later, a couple was arrested and tried for kidnapping and murder on circumstantial evidence. According to the Daily Mail, the couple were inspired by the film Dirty Harry, in which Scorpio kidnaps a girl and places her in an underground box.[69] This case was also dealt with in the German TV series Aktenzeichen XY ... ungelöst.

Influence

Eastwood's iconic portrayal of the blunt, cynical, unorthodox detective, who is seemingly in perpetual trouble with his incompetent bosses, set the style for a number of his later roles and, indeed, a whole genre of "loose-cannon" cop films. The film resonated with an American public that had become weary and frustrated with the increasing violent urban crime that was characteristic of the time.[70] The film was released at a time when there were frequent reports of local and federal police committing offences and overstepping their authority by entrapment and obstruction of justice.[71] Author McGilligan, argued that America needed a hero, a winner at a time when the authorities were losing the battle against crime.[71] The box-office success of Dirty Harry led to the production of four sequels.

The Fred Williamson blaxploitation film Black Cobra, mimicked the famous 'Do You Feel Lucky, Punk?' scene from Dirty Harry. The same scene was parodied in The Mask in 1994 and in The Man Who Knew Too Little in 1997. The British virtual band Gorillaz also entitled a song "Dirty Harry" on their album Demon Days. The film can also be counted as the chief influence on the Italian tough-cop films, Poliziotteschi, which dominated the 1970s and that were critically praised in Europe and the U.S. as well.

Dirty Harry helped popularize the Smith & Wesson Model 29 revolver, chambered for the powerful .44 Magnum cartridge. The film initiated an increase in sales of the powerful handgun, which continues to be popular forty years after the film's release.[72] The .44 Magnum ranked second in a 2008 20th Century Fox poll of the most popular film weapons, after only the lightsaber of Star Wars fame. The poll surveyed approximately two thousand film fans.[73] However, the only appearances of the Model 29 in the movie are in the close-ups: Any time Eastwood actually fired the revolver, he was shooting a Smith & Wesson Model 25 in .45 Long Colt. The reason was that in 1971 .45 caliber 5-in-1 blank cartridges were readily available, while .44 caliber blanks did not exist. As the Model 25 and Model 29 are both built on the Smith & Wesson N frame, visually they are almost indistinguishable.

In the 2004 film Starsky & Hutch The movie poster was briefly shown when Hutch is carrying Starsky up the stairs after the Disco, due to his influence on Cocaine.

In the 2007 film Zodiac, also inspired by the Zodiac Killer, cartoonist Robert Graysmith approaches police detective Dave Toschi at the cinema, where he is watching Dirty Harry with his wife. When Graysmith tells Toschi he is going to catch the Zodiac killer, Toschi replies, "Pal? They're already making movies about it."[74]

In 2010, artist James Georgopoulos included the screen-used guns from Dirty Harry in his popular Guns of Cinema series.[75]

The 2013 satirical comedy film InAPPropriate Comedy parodied the character Dirty Harry with a fake trailer called "Flirty Harry", in which Flirty Harry was played by Adrien Brody.

The 2014 video game Sunset Overdrive features a gun with the same name.

See also

References

Notes

- 1 2 "Dirty Harry". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 19, 2009.

- ↑ Jenkins, John Philip. "Zodiac Killer." Encyclopaedia Britannica at Britannica.com. Retrieved 2015-05-06.

- ↑ "'Dirty Harry' Among Films Enshrined in National Film Registry". Hollywoodreporter.com. December 19, 2012. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Hughes, p. 49.

- 1 2 McGilligan (1999), p. 205.

- ↑ Munn, Michael, John Wayne: The Man Behind The Myth, pgs unknown

- ↑ Eliot (2009), p. 134.

- 1 2 Eliot (2009), p. 133.

- ↑ P, Ken. "An Interview with John Milius". IGN.

- ↑ Malick, Milius & Fink, Dirty Harry November 1970 Script.

- ↑ Buford, Kate; Burt Lancaster: An American Life.

- ↑ Richard Schickel commentary, Dirty Harry Two-Disc Special Edition DVD.

- ↑ Horowitz, Josh (June 23, 2008). "Clint Eastwood Talks About How He Ended Up In 'Dirty Harry,' Whether He'd Return To The Iconic Role". MTV.

- ↑ Hughes, p. 52.

- ↑ Rock, Philip, Dirty Harry.

- 1 2 Hughes, p. 50.

- 1 2 3 McGilligan (1999), p. 207.

- ↑ "Anecdotage.Com". Anecdotage.Com. September 29, 2012. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Thompson, Richard (July–August 1976). "STOKED". Film Comment 12.4. p. 10-21.

- ↑ Clint Eastwood Collection edition Dirty Harry (2001: Warner Brothers DVD): Interview Gallery:John Milius

- ↑ "The National Firearms Museum: Dirty Harry (1971) Smith & Wesson 29". Nramuseum.com. Archived from the original on May 13, 2012. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Eliot (2009), p.138

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p. 206

- ↑ "Dirty Harry Filming and pictures of (now closed) rooftop swimming pool - Mr. SF". Mistersf.com. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ↑ 666 Filbert St (January 1, 1970). "666 Filbert Street, San Francisco, CA 94133 - Google Maps". Maps.google.com. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ↑ "Washington Square, San Francisco, CA - Google Maps". Maps.google.com. November 4, 2013. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ↑ Krausgrill Pl (January 1, 1970). "Krausgrill Place, San Francisco, CA 94133 - Google Maps". Maps.google.com. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ↑ Medau Pl (January 1, 1970). "Medau Place, San Francisco, CA 94133 - Google Maps". Maps.google.com. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ↑ Jasper (January 1, 1970). "Jasper, San Francisco, CA 94133 - Google Maps". Maps.google.com. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ↑ "FINALE – Hutchinson Co. Quarry, Larkspur Landing, CA - Dirty Harry Filming Locations". Dirtyharryfilminglocations.wordpress.com. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ↑ "20sep2002 Dirty Harry Movie Tour / mvc-3540". Acme.com. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ↑ 100 Old Quarry Rd N (January 1, 1970). "100 Old Quarry Road North, Larkspur, CA (Larkspur Court Apartments ) - Google Maps". Maps.google.com. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ↑ Larkspur Ferry Terminal - Google Maps

- ↑ "Golden Gate Ferry Research Library". Goldengateferry.org. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ↑ Review by J.T. Lindroos (allmusic.com). Retrieved April 15, 2010.

- ↑ Review by Andrew Keech (musicfromthemovies.com). Retrieved April 15, 2010.

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p. 211

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p. 210.

- ↑ Hagen, Dan (January 1988). "Neal Gabler". Comics Interview (54). Fictioneer Books. pp. 61–63.

- ↑ Roger Ebert (January 1, 1971). "Dirty Harry (review)". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved March 3, 2009.

- ↑ Clint Eastwood filmography. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

- ↑ Eastwood Talks Dirty Harry. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

- ↑ "Empire's The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ↑ "The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made". The New York Times. April 29, 2003. Retrieved April 15, 2010.

- ↑ "Total Film features: 100 Greatest Movies of All Time". Total Film. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- ↑ "50 Greatest Movies (on TV and Video) by TV GUIDE Magazine". TV Guide. AMC/FilmSite.org. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ↑ "50 Greatest Films by Vanity Fair Magazine". Vanity Fair. Published by AMC FilmSite.org. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ↑ "Top Movies - Best Movies of 2012 and All Time". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- ↑ "The Greatest Films of 1971". AMC Filmsite.org. Retrieved April 15, 2010.

- ↑ "The Best Movies of 1971 by Rank". Films101.com. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ↑ Dirty Harry Movie Reviews, Pictures - Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved April 15, 2010.

- ↑ 1972 Edgar Allan Poe Awards. Who's Dated Who. Retrieved December 4, 2013.

- ↑ "The 100 best action movies". Time Out. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ↑ "The 100 best action movies: 80-71". Time Out. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ↑ "1077 Market Street (Grauman's Imperial, 1912; Imperial, 1916; Premier, 1929; United Artists, 1931; Loew's, 1970; Market Street Cinema, 1972)". Upfromthedeep.com. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ↑ "KPIX-TV newsclip from the world premiere of Dirty Harry". Diva.sfsu.edu. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ↑ "download MPEG4 newsclip". Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ↑ "Dirty Harry Movies". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 19, 2009.

- ↑ "New Dirty Harry DVDs: We're in luck". March 10, 2008. Retrieved April 15, 2010.

- ↑ "Dirty Harry". iTunes Store. Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Thrills" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Heroes and Villains" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movie Quotes" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movies: Official Ballot" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition): Official Ballot" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores: Official Ballot" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Australis-Obits-L Archives". Ancestry.com. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ↑ "Time Capsule: Entire school kidnapped". The Australian. October 6, 2007. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ↑ Clint Eastwood Film Dirty Harry Inspired Couple Kidnap Little Girl, 10, for Ransom, Court Told. Daily Mail. retrieved September 27, 2011

- ↑ "Flashback Five - The Best Dirty Harry Movies". American Movie Classics. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- 1 2 McGilligan (1999), p. 209

- ↑ United Stuff of America, "American Firepower," Series 1, Episode 2, 2014

- ↑ Borland, Sophie (January 21, 2008). "Lightsabre wins the battle of movie weapons". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

- ↑ (PDF) http://www.screenplaydb.com/film/scripts/Zodiac.PDF. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ The Shooting Range, Treats Magazine, March 2013

Bibliography

- Street, Joe, “Dirty Harry’s San Francisco,” The Sixties: A Journal of History, Politics, and Culture, add ci 5 (June 2012), 1–21.

- Eliot, Marc (2009). American Rebel: The Life of Clint Eastwood. Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0-307-33688-0.

- Hughes, Howard (2009). Aim for the Heart. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-902-7.

- McGilligan, Patrick (1999). Clint: The Life and Legend. London: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-638354-8.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Dirty Harry |

- Official website

- Dirty Harry at the Internet Movie Database

- Dirty Harry at the TCM Movie Database

- Dirty Harry at AllMovie

- Dirty Harry at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Dirty Harry at Rotten Tomatoes

- Dirty Harry at Box Office Mojo

- Dirty Harry filming locations

- DIRTY HARRY ON LOCATION