Economy of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

| Currency | Yugoslav dinar (YUD) |

|---|---|

| 1 January – 31 December (calendar year)[1] | |

| Statistics | |

| GDP | $120,100 million (24th) (1991 est.)[2] |

| GDP rank | 24th (1991)[2] |

GDP growth | -6.3% (1991)[3] |

GDP per capita |

$5,040 (59th) (1991 est., nominal)[4] $3,549 (1990, at current prices)[5] |

| 164% (7th) (1991 est.)[6] | |

Labour force | 9,600,000 (32nd) (1991 est.)[7] |

| Unemployment | 16% (21st) (1991 est.)[8] |

Main industries | metallurgy, machinery and equipment, petroleum, chemicals, textiles, wood processing, food processing, pulp and paper, motor vehicles, building materials[1] |

| External | |

| Exports | $13.1 billion (39th) (1991 est.)[9] |

| Imports | $17.6 billion (32nd) (1991 est.)[10] |

Gross external debt | $18 billion (36th) (1991 est.)[11] |

| Public finances | |

| Revenues | $6.4 billion (51st) (1991 est.)[12] |

| Expenses | $6.4 billion (52nd) (1991 est.)[13] |

| Economic aid | $3.5 billion (1966-88)[1] |

|

All values, unless otherwise stated, are in US dollars. | |

Despite common origins, the economy of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY) was significantly different from the economies of the Soviet Union and other Eastern European socialist states, especially after the Yugoslav-Soviet break-up of 1948. The occupation and liberation struggle in World War II left Yugoslavia's infrastructure devastated. Even the most developed parts of the country were largely rural and the little industry the country had was largely damaged or destroyed.

Post-war years

The first postwar years saw implementation of Soviet-style five-year plans and reconstruction through massive voluntary work. The countryside was electrified and heavy industry was developed. The economy was organized as a mixture of planned socialist economy and a market socialist economy: factories were nationalized, and workers were entitled to a certain share of their profits.

Privately owned craftshops could employ up to 4 people per owner. The land was partially nationalised and redistributed, and partially collectivised. Farmer households could own up to 10 hectares of land per person and the excess farmland was owned by co-ops, agricultural companies or local communities. These could sell and buy land, as well as give it to people in perpetual lease.

Youth work actions

| Name | Length(km) | Released |

|---|---|---|

| Brčko-Banovići | 98 | 1946 |

| Šamac-Sarajevo | 242 | 1947 |

| Bihać-Knin | 112 | 1948 |

| Sarajevo-Ploče | 195 | 1966 |

| Belgrade-Bar | 227 | 1976[14] |

Youth work actions were organized voluntary labor activities of young people in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The actions were used to build public infrastructure such as roads, railways, and public buildings, as well as industrial infrastructure. The youth work actions were organized on local, republic and federal levels by the Young Communist League of Yugoslavia, and participants were organized into youth work brigades, generally named after their town or a local national hero. Important projects built by youth work brigades include the Brčko-Banovići railway, the Šamac-Sarajevo railway, parts of New Belgrade, and parts of the Highway of Brotherhood and Unity, which stretches from northern Slovenia to southern Macedonia.

1950s and 1960s

In the 1950s socialist self-management was introduced, which reduced the state management of enterprises. Managers of socially owned companies were supervised by worker councils, which were made up of all employees, with one vote each. The worker councils also appointed the management, often by secret ballot. The Communist Party was organized in all companies and most influential employees were likely to be members of the party, so the managers were often, but not always, appointed only with the consent of the party. Although GDP is not technically applicable or designed to measure planned economies: in 1950 Yugoslavia's GDP ranked twenty-second in Europe.[15]

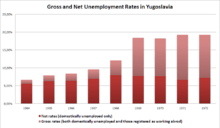

Unemployment was a chronic problem for Yugoslavia,[16] the unemployment rates were amongst the highest in Europe during its existence, while the education level of the work force increased steadily. Due to Yugoslavia's non-alignment, and its leading role in the Non-Aligned Movement, Yugoslav companies exported to both Western and Eastern markets. Yugoslav companies carried out construction of numerous major infrastructural and industrial projects in Africa, Europe and Asia. In 1965, a new dinar was introduced. The previous dinar, traded at a rate of 700 to the U.S. dollar, was replaced with a new dinar traded at 12.5 to the U.S. dollar.[17]

The departure of Yugoslavs seeking work began in the 1950s, when individuals began slipping across the border illegally. In the mid-1960s, Yugoslavia lifted emigration restrictions and the number of emigrants, including educated and highly skilled individuals increased rapidly, especially to West Germany. By the early 1970s 20 percent of the country's labor force or 1,1 million workers were employed abroad.[18] The emigration was mainly caused by force deagrarization, deruralization, and overpopulating of larger towns.[19] The emigration contributed to keeping the unemployment checked and also acted as a source of capital and foreign currency. The system was institutionalized into the economy.[20] From 1961 to 1971, the number of guest workers from Yugoslavia in West Germany increased from 16,000 to 410,000.[21]

1970s

In the 1970s, the economy was reorganised according to Edvard Kardelj's theory of associated labour, in which the right to decision making and a share in profits of socially owned companies is based on the investment of labour. All industrial companies were transformed into organisations of associated labour. The smallest, basic organisations of associated labour, was roughly corresponded to a small company or a department in a large company. These were organised into enterprises, also known as labour organisations, which in turn associated into composite organisations of associated labour, which could be large companies or even whole industry branches in a certain area. Basic organisations of associated labour sometimes were composed of even smaller labour units, but they had no financial freedom. Also, composite organisations of associated labour were sometimes members of business communities, representing whole industry branches. Most executive decision making was based in enterprises, so that these continued to compete to an extent even when they were part of a same composite organisation. The appointment of managers and strategic policy of composite organisations were, depending on their size and importance, in practice often subject to political and personal influence-peddling.

In order to give all employees the same access to decision making, the basic organisations of associated labour were also introduced into public services, including health and education. The basic organisations were usually made up of dozens of people and had their own workers councils, whose assent was needed for strategic decisions and appointment of managers in enterprises or public institutions.

The workers were organized into trade unions which spanned across the country. Strikes could be called by any worker, or any group of workers and they were common in certain periods. Strikes for clear genuine grievances with no political motivation usually resulted in prompt replacement of the management and increase in pay or benefits. Strikes with real or implied political motivation were often dealt with in the same manner (individuals were prosecuted or persecuted separately), but occasionally also met stubborn refusal to deal or in some cases brutal force. Strikes occurred in all times of political upheaval or economic hardships, but they became increasingly common in the 1980s, when consecutive governments tried to salvage the slumping economy with a programme of austerity under the auspices of the International Monetary Fund.

From 1970 onwards, despite 29% of its population working in agriculture, Yugoslavia was a net importer of farm products.[23]

Effect of the oil crisis

The oil crisis of the 1970s magnified the economic problems, the foreign debt grew at an annual rate of 20%, and by the early 1980s it reached more than US$20 billion.[24] Governments of Milka Planinc and Branko Mikulić renegotiated the foreign debt at the price of introducing the policy of stabilisation which in practice consisted of severe austerity measures — the so-called shock treatment. During the 1980s, Yugoslav population endured the introduction of fuel limitations (40 litres per car per month), limitation of car usage to every other day, based on the last digit on the licence plate, severe limitations on import of goods and paying of a deposit upon leaving the country (mostly to go shopping), to be returned in a year (with rising inflation, this effectively amounted to a fee on travel). There were shortages of coffee, chocolate and washing powder. During several dry summers, the government, unable to borrow to import electricity, was forced to introduce power cuts. On May 12, 1982 the Board of the International Monetary Fund approved enhanced surveillance of Yugoslavia, to include Paris Club creditors.[25]

Collapse of the Yugoslav economy

| Year | Debt | Inflation | Unemployment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1954 | $400 million[26] | ||

| 1965 | $1.2 billion[14] | 34,6%[27] | 6,6%[28] |

| 1971 | $3.177 billion[14] | ||

| 1973 | $4.7 billion[29] | 20%[30] | 9,1%[28] |

| 1980 | $18.9 billion[29] | 27%[31] | 13,8%[28] |

| 1982 | $20 billion[29] | 40%[32] | 14,4%[28] |

| 1987 | $21.961 billion[14] | 167%[33] | 16,1%[28] |

In the 1980s the Yugoslav economy entered a period of continuous crisis. Between 1979 and 1985 the Yugoslav dinar plunged from 15 to 1,370 to the U.S. dollar, half of the income from exports was used to service the debt, while real net personal income declined by 19.5%. Unemployment rose to 1.3 million job-seekers, and internal debt was estimated at $40 billion.[34]

Yugoslavia took on a number of International Monetary Fund (IMF) loans and subsequently fell into heavy debt. By 1981, it had incurred $18.9 billion in foreign debt.[29] However, Yugoslavia’s main concern was unemployment. In 1980 the unemployment rate was at 13,8%,[28] not counting around 1 million workers employed abroad.[31] Deteriorating living conditions during the 1980s caused the Yugoslavian unemployment rate to reach 17 percent, while another 20 percent were underemployed. 60% of the unemployed were under the age of 25.[16] By 1988 emigrant remittances to Yugoslavia totalled over $4.5 billion (USD), and by 1989 remittances were $6.2 billion (USD), which amounted to over 19% of the world's total.[35][36] In 1988 Yugoslavia owed $21 billion to Western countries.[37]

The collapse of the Yugoslav economy was partially caused by its non-aligned stance that had resulted in access to loans from both superpower blocs.[38] This contact with the United States and the West opened up Yugoslav markets sooner than in the rest of Central and Eastern Europe. In 1989, before the fall of the Berlin Wall, Yugoslav federal Prime Minister Ante Marković went to Washington to meet with President George H. W. Bush, to negotiate a new financial aid package. In return for assistance, Yugoslavia agreed to even more sweeping economic reforms, which included a new devalued currency, another wage freeze, sharp cuts in government spending, and the elimination of socially owned, worker-managed companies.[39] The Belgrade nomenclature, with the assistance of western advisers, had laid the groundwork for Marković's mission by implementing beforehand many of the required reforms, including a major liberalization of foreign investment legislation.

This was in part muted by the spectacular draining of the banking system, caused by the rising inflation, in which millions of people were effectively forgiven debts or even allowed to make fortunes on perfectly legal bank-milking schemes. The banks adjusted their interest rates to the inflation, but this could not be applied to loan contracts made earlier which stipulated fixed interest rates. Debt repayments for privately owned housing, which was massively built during the prosperous 1970s, became ridiculously small and as a result banks suffered huge losses. Indexation was introduced to take inflation into account, but the resourceful population continued to drain the system through other schemes, many of them having to do with personal cheques.

Personal cheques were widely used in Yugoslavia in pre-inflation times. Cheques, which were considered legal tender, were accepted by all businesses. They were processed by hand and mailed by regular post, so there was no way to ensure real-time accounting. The banks therefore continued to deduct money from current accounts on the date they received the cheque, and not on the date it was issued. When inflation rose to triple and then quadruple digits, this allowed another widespread form of cost reduction or outright milking of the system. Bills from remote places would arrive six months late, causing losses to businesses. Since banks maintained no-fee mutual customer service, people would travel to small banks in rural areas on the other end of the country and cash in several cheques. They would then exchange the money for foreign currency, usually German mark and wait for the cheque to arrive. They would then convert a part of the foreign currency amount and repay their debt, greatly reduced by inflation. Companies, struggling to pay their work-force, adopted similar tactics.

New legislation was gradually introduced to remedy the situation, but the government mostly tried to fight the crisis by issuing more currency, which only fuelled the inflation further. Power-mongering in big industrial companies led to several large bankruptcies (mostly of large factories), which only increased the public perception that the economy is in a deep crisis. After several failed attempts to fight the inflation with various schemes, and due to mass strikes caused by austerity wage freezes, the government of Branko Mikulić was replaced by a new government in March 1989, headed by Ante Marković, a pragmatic reformist. He spent a year introducing new business legislation, which quietly dropped most of the associated labour theory and introduced private ownership of businesses.[40] The institutional changes culminated in eighteen new laws that declared an end to the self-management system and associated labor.[41] While public companies were allowed to be partially privatised, mostly through investment, the concepts of social ownership and worker councils were still retained.

By the end of 1989 inflation reached 1,000%.[42] On New Year's Eve 1989, Ante Marković introduced his program of economic reforms. Ten thousand Dinars became one "New Dinar", pegged to the German Mark at the rate of 7 New Dinars for one Mark.[43] The sudden end of inflation brought some relief to the banking system. Ownership and exchange of foreign currency was deregulated which, combined with a realistic exchange rate, attracted foreign currency to the banks. However, by the late 1980s, it was becoming increasingly clear that the federal government was effectively losing the power to implement its programme.[44]

Early 1990s

In 1990 Marković introduced a privatization program, with newly passed federal laws on privatization allowing company management boards to initiate privatization, mainly through internal share-holding schemes, initially not tradable in the stock exchange.[45] This meant that the law put an emphasis on "insider" privatization to company workers and managers, to whom the shares could be offered at a discount. Yugoslav authorities used the term "property transformation" when referring to the process of transforming public ownership into private hands.[40] By April 1990, the monthly inflation rate dropped to zero, exports and imports increased, while foreign currency reserves increased by US$3 billion. However, industrial production fell by 8.7% and high taxes made it difficult for many enterprises to pay even the frozen wages.[44][46]

In July 1990, Marković formed his own Union of Reform Forces political party. By the 2nd half of 1990 inflation restarted. In September and October the monthly inflation rate reached 8%. Inflation once more climbed to unmanageable levels reaching an annual level of 120%. Marković's reforms and austerity programs met resistance from the federal authorities of the individual republics. His program of 1989 to curb inflation was rejected by Serbia and Vojvodina. SR Serbia introduced customs duties on imports from Croatia and Slovenia and took $1,5 billion from the central bank to fund wage rises, pensions, bonuses to government employees and subsidize enterprises that faced losses.[40][46] The federal government raised the exchange rate for the German Mark first to 9 and then to 13 dinars. In 1990 the annual rate of GDP growth had declined to -11.6%.[5]

Yugoslav economy in numbers – 1990

(SOURCE: 1990 CIA WORLD FACTBOOK)[47]

Inflation rate (consumer prices): 2,700% (1989 est.)

Unemployment rate: 15% (1989)

GDP: $129.5 billion, per capita $5,464; real growth rate - 1.0% (1989 est.)

Budget: revenues $6.4 billion; expenditures $6.4 billion, including capital expenditures of $NA (1990)

Exports: $13.1 billion (f.o.b., 1988); commodities—raw materials and semimanufactures 50%, consumer goods 31%, capital goods and equipment 19%; partners—EC 30%, CEMA 45%, less developed countries 14%, US 5%, other 6%

Imports: $13.8 billion (c.i.f., 1988); commodities—raw materials and semimanufactures 79%, capital goods and equipment 15%, consumer goods 6%; partners—EC 30%, CEMA 45%, less developed countries 14%, US 5%, other 6%

External debt: $17.0 billion, medium and long term (1989)

Electricity: 21,000,000 kW capacity; 87,100 million kWh produced, 3,650 kWh per capita (1989)

GDP per capita of major cities

| City | Residents (1991 Census) |

GDP Index (Yugoslavia=100) |

Republic |

| Belgrade | 1,552,151 | 147 | SR Serbia |

| Zagreb | 777,826 | 188 | SR Croatia |

| Sarajevo | 527,049 | 133 | SR Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| Skopje | 506,926 | 90 | SR Macedonia |

| Ljubljana | 326,133 | 260 | SR Slovenia |

| Novi Sad | 299,294 | 172 | SR Serbia |

| Niš | 253,124 | 110 | SR Serbia |

| Split | 221,456 | 137 | SR Croatia |

| Banja Luka | 195,692 | 97 | SR Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| Pristina | 155,499 | 70 | SR Serbia |

| Kragujevac | 144,608 | 114 | SR Serbia |

| Rijeka | 143,964 | 213 | SR Croatia |

| Podgorica | 136,473 | 87 | SR Montenegro |

The post-war regime

For later developments, see: Economy of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Economy of Croatia, Economy of the Republic of Macedonia, Economy of Montenegro, Economy of Serbia, Economy of Slovenia.

The Yugoslav wars, consequent loss of market, as well as mismanagement and/or non-transparent privatization brought further economic trouble for all former republics of Yugoslavia in the 1990s. Only Slovenia's economy grew steadily after the initial shock and slump. Croatia's secession resulted in direct damages worth $43 billion (USD).[49] Croatia reached its 1990 GDP in 2003, a few years after Slovenia, the most advanced of all Yugoslav economies by far.

References

- 1 2 3 Yugoslavia Economy - 1990. CIA Factbook. 1992. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- 1 2 GDP/GNP Million 1991. CIA Factbook. 1992. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- ↑ GDP/GNP Growth Rate 1991. CIA Factbook. 1992. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- ↑ Per Capita GDP/GNP 1991. CIA Factbook. 1992. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- 1 2 National Accounts Main Aggregates Database

- ↑ Inflation Rate % 1992. CIA Factbook. 1992. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- ↑ Labor Force 1992. CIA Factbook. 1992. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- ↑ Unemployment rate % 1992. CIA Factbook. 1992. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- ↑ Export Million 1992. CIA Factbook. 1992. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- ↑ Imports Million 1992. CIA Factbook. 1992. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- ↑ External Debt Million 1992. CIA Factbook. 1992. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- ↑ Budget Revenues Million 1992. CIA Factbook. 1992. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- ↑ Budget Expenditures Million 1992. CIA Factbook. 1992. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 http://www.znaci.net/00001/120_5.pdf

- ↑ Marilyn Rueschemeyer. Women in the Politics of Postcommunist Eastern Europe. M.E. Sharpe, 1998. (pg. 200)

- 1 2 Mieczyslaw P. Boduszynski: Regime Change in the Yugoslav Successor States: Divergent Paths toward a New Europe, p. 66-67

- ↑ John R. Lampe, Russell O. Prickett, Ljubiša S. Adamović. Yugoslav-American Economic Relations Since World War II. Duke University Press, 1990. (pg. 83)

- ↑ The Library of Congress Country Studies; CIA World Factbook

- ↑ Dražen Živić, Nenad Pokos and Ivo Turk. Basic Demographic Processes in Croatia

- ↑ Richard C. Frucht. Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. ABC-CLIO, 2005. (pg. 574)

- ↑ Anthony M. Messina. The Logics and Politics of Post-WWII Migration to Western Europe. Cambridge University Press, 2007. (pg. 125)

- ↑ Susan L. Woodward: Socialist Unemployment: The Political Economy of Yugoslavia, 1945-1990, p. 199, 378

- ↑ Alice Teichova, Herbert Matis. Nation, State, and the Economy in History. Cambridge University Press, 2003. (pg. 209)

- ↑ Mieczyslaw P. Boduszynski: Regime Change in the Yugoslav Successor States: Divergent Paths toward a New Europe, p. 64

- ↑ James M. Boughton, Silent revolution: the International Monetary Fund, 1979-1989. International Monetary Fund, 2001. (p.434)

- ↑ Yugoslavs Ask West's Aid On Easing Debt Problem, Daytona Beach Morning Journal. December 28, 1954.

- ↑ Statistički bilten 803, (Statistical Bulletin), SZS, Beograd, September 1973.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Susan L. Woodward: Socialist Unemployment: The Political Economy of Yugoslavia, 1945-1990, p. 377

- 1 2 3 4 OECD Economic Surveys: Yugoslavia 1990, p. 34

- ↑ Fires of "revisionist heresy" choking in Yugoslavia, Gadsden Times. June 1, 1974.

- 1 2 Prize for another time

- ↑ A Quiet Transition in Yugoslavia

- ↑ OECD Economic Surveys: Yugoslavia 1988, p. 9

- ↑ Mieczyslaw P. Boduszynski: Regime Change in the Yugoslav Successor States: Divergent Paths toward a New Europe, p. 64-65

- ↑ Beth J. Asch, Courtland Reichmann, Rand Corporation. Emigration and Its Effects on the Sending Country. Rand Corporation, 1994. (pg. 26)

- ↑ Douglas S. Massey, J. Edward Taylor. International Migration: Prospects and Policies in a Global Market. Oxford University Press, 2004. (pg. 159)

- ↑ Yugoslavia's President Says Crisis Harms the Country's Reputation

- ↑ http://www.monitor.net/monitor/9904a/yugodismantle.html. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Gervasi, op. cit., p. 44

- 1 2 3 Patrick Heenan, Monique Lamontagne: Central and Eastern Europe Handbook, Routledge, 2014, p. 96

- ↑ Susan L. Woodward: Socialist Unemployment: The Political Economy of Yugoslavia, 1945-1990, p. 256

- ↑ Sabrina P. Ramet: The Three Yugoslavias: State-building and Legitimation, 1918-2005, Indiana University Press, 2006, p. 363

- ↑ OECD Economic Surveys: Yugoslavia 1990, p. 86

- 1 2 http://www.mongabay.com/history/yugoslavia/yugoslavia-the_reforms_of_1990.html

- ↑ Milica Uvalic: Investment and Property Rights in Yugoslavia: The Long Transition to a Market Economy, Cambridge University Press, 2009, p. 185

- 1 2 John R. Lampe: Yugoslavia as History: Twice There Was a Country, Cambridge University Press, 2000, p. 357

- ↑ 1990 CIA WORLD FACTBOOK

- ↑ Radovinović, Radovan; Bertić, Ivan, eds. (1984). Atlas svijeta: Novi pogled na Zemlju (in Croatian) (3rd ed.). Zagreb: Sveučilišna naklada Liber.

- ↑ Alex J. Bellamy. The Formation of Croatian National Identity: A Centuries-old Dream. Manchester University Press, 2003. (pg. 105)

Additional reading

- Yugoslavia: Trouble in the Halfway House by Melvin D. Barger

- SELF-MANAGEMENT AND REQUIREMENTS FOR SOCIAL PROPERTY: LESSONS FROM YUGOSLAVIA by DIANE FLAHERTY

- Damachi, U.G. & H.D. Seibel (Eds.) Self Management in Yugoslavia and the Developing World. London, Macmillan, 1982

- This Was My Yugoslavia By Vladimir Unkovski

- Yugoslavia (former) Banking