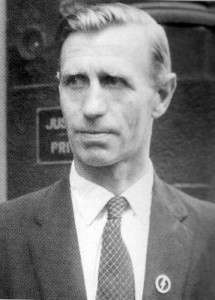

Jeffrey Hamm

| Jeffrey Hamm | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Edward Jeffrey Hamm 15 September 1915 Ebbw Vale, Wales |

| Died | 4 May 1992 (aged 76) |

| Political party | British Union of Fascists, Union Movement |

Edward Jeffrey Hamm (15 September 1915 – 4 May 1992) was a leading British Fascist and supporter of Oswald Mosley. Although a minor figure in Mosley's pre-war movement he became a leading figure after the Second World War and eventually succeeded as leader of the Union Movement on Mosley's retirement.

Early life

Hamm was born in Ebbw Vale, Wales, whilst his father was serving in the First World War. The family later relocated to Monmouth.[1] It has been claimed that he first became attracted to the British Union of Fascists (BUF) in 1934 when, on a trip to London, he chanced upon a party member delivering a speech and was impressed.[1]

British Union of Fascists

He joined the BUF in 1935 when he relocated to London to take up a teaching role at King's School, Harrow.[2] A young member, Hamm did not rise above the rank and file in the BUF. In 1939 he moved to the Falkland Islands to work as a teacher, and it was there that he was arrested in 1940 under Defence Regulation 18B after being accused of encouraging fascism amongst his pupils.[2] He was transferred to Leuwkop in South Africa, where he was involved in an attempt to tunnel out of the camp.[3] The camp also contained a number of German Nazi prisoners and a contemporary MI5 report suggested Hamm had been indoctrinated by Nazi propaganda by his fellow inmates.[2] He was returned to Britain in 1941 and enlisted in the Royal Tank Regiment but during his service Hamm was marked out as disruptive influence and was taken off the front before being discharged in 1944.[2][4] He found work in the Royal Coach Works in Acton following his discharge[2] and subsequently was a bookkeeper at a milliner shop.[5]

Around this time Hamm converted to the Roman Catholic Church under the influence of Father Clement Russell, a Nazi sympathiser and anti-Semite based in Wembley who kept a photograph of Mosley on display in his parochial house.[2] Hamm and his wife were married by Russell, with the climax of the ceremony coming with the couple saluting a Nazi flag.[6]

Return to politics

Hamm had been a minor figure in the BUF but his time in the prison camps had increased his support for Mosley.[7] Indeed, such had been his low standing in the movement that Mosley did not know who he was and for a time struggled to spell Hamm's surname properly.[8] Nonetheless Hamm quickly became the most vigorous and vocal of Mosley's post-internment supporters.[9]

Following his discharge, Hamm joined and then took over the British League of Ex-Servicemen and Women, which claimed to look after veterans' interests, and converted it to a movement designed to keep Mosley's ideas current.[6] Seeking to keep British Fascism alive, Hamm organized a series of meetings in Hyde Park from November 1944 onwards, later moving them to the traditional BUF areas of east London. Hamm's League rallies eventually began to attract thousands, convincing him that a proper political return was a distinct possibility. Hamm's rallies also attracted significant opposition, with clashes between his supporters and anti-fascists.[10] However the group's first public campaign actually took place in the Metropolitan Borough of Hampstead, where it helped to organise a petition to keep immigrants out of new houses, ostensibly on the pretext that the housing should be kept for returning soldiers.[11] As a result of his involvement, Hamm secured publicity for the League and it also gave him access to leading figures such as Ernest Benn and Waldron Smithers, who had been involved in drawing up the petition in the first place.[11]

Hamm's increasing profile did not go unnoticed by supporters and opponents alike and in 1946 he and his ally Victor Burgess were both on the end of a severe beating from anti-fascists.[11] A similar incident in Brighton in 1948 resulted in Hamm spending time in hospital.[12] Mosley was initially unsure of Hamm but at a secret meeting in Bethnal Ggreen on 22 December 1946 he endorsed Hamm's leadership and declared Hamm his "East End representative", east London being traditionally the epicentre of Mosleyite activity.[11] In 1947 however Mosley would censure Hamm for the violent and inflammatory nature of much of his propaganda, forcing Hamm to tone down his rhetoric.[13]

Union Movement

He soon began calling on Mosley to return to the leadership of British fascism.[14] Hamm incorporated his British League into the Union Movement (UM) immediately upon the latter's foundation in 1948.[7] Hamm became a leading member of the new UM although he was considered a spiky figure and was unpopular at UM headquarters, to the extent that Mosley sent him to Manchester in 1949. Hamm failed to revitalise the northern branch and contemplated leaving the UM altogether until being recalled by Mosley in 1952.[15] Returning to London, Hamm became a central figure in the new anti-black campaign of the UM, which won it some support in Brixton and other areas where new West Indies immigrants were settling.[16] He gained widespread press coverage when, in the immediate aftermath of the 1958 Notting Hill race riots, he made a speech outside Latimer Road tube station.[17]

In the later years of the UM, Hamm served as Mosley's personal secretary, succeeding to the post upon the death of Alexander Raven Thomson in 1955.[7] Like Mosley he was an ardent supporter of Irish unity and encouraged his leader to campaign on this issue.[18] Hamm stood as a candidate for it in the 1966 general election in the Handsworth constituency. He polled 4% of the vote. Mosley effectively withdrew from public life after this, and the UM came under the leadership of Hamm and Robert Row, the last two paid UM activists.[19]

Mosley was officially UM leader until 1973 when he formally retired, at which point Hamm, by that point effective leader, formally succeeded him.[20] Under Hamm the party relaunched as the Action Party, and under this title contested the 1973 Greater London Council elections, without success.[21] The party transformed itself into the Action Society in 1978, giving up party politics to become a publishing house.[21]

Hamm published his autobiography, Action Replay, in 1983, and then in 1988 his second book, The Evil Good Men Do. He died from Parkinson's disease in 1992. The Papers of Jeffrey Hamm are housed at the University of Birmingham Special Collections.

Elections contested

| Date of election | Constituency | Party | Votes | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 March 1962 | Middlesbrough East | Union Movement | 550 | 1.7 |

| 31 March 1966 | Birmingham Handsworth | Union Movement | 1337 | 4.1 |

References

- 1 2 Biography at Friends of Oswald Mosley site

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Graham Macklin, Very Deeply Dyed in Black, IB Tauris, 2007, p. 38

- ↑ Richard Thurlow, Fascism in Britain A History, 1918-1985, Basil Blackwell, 1987, p. 224

- ↑ Stephen Dorril, Blackshirt - Sir Oswald Mosley & British Fascism, Penguin, 2007, p. 542

- ↑ Dorril, Blackshirt, p. 547

- 1 2 Macklin, Very Deeply Dyed in Black, p. 39

- 1 2 3 Thurlow, Fascism in Britain, p. 243

- ↑ Macklin, Very Deeply Dyed in Black, p. 16

- ↑ Macklin, Very Deeply Dyed in Black, pp. 15-16

- ↑ Thurlow, Fascism in Britain, p. 231

- 1 2 3 4 Macklin, Very Deeply Dyed in Black, p. 40

- ↑ Macklin, Very Deeply Dyed in Black, p. 53

- ↑ Macklin, Very Deeply Dyed in Black, p. 48

- ↑ Dorril, Blackshirt, p. 553

- ↑ Macklin, Very Deeply Dyed in Black, p. 58

- ↑ Macklin, Very Deeply Dyed in Black, p. 71

- ↑ Robert Skidelsky, Oswald Mosley, Macmillan, 1981, p. 510

- ↑ Skidelsky, Oswald Mosley, p. 513

- ↑ Dorril, Blackshirts, p. 630

- ↑ S. Taylor, The National Front in English Politics, Macmillan, 1982, p. 17

- 1 2 David Boothroyd, The History of British Political Parties, Politcos, 2001, p. 3