Emperor Huizong of Song

| Emperor Huizong of Song 宋徽宗 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||

| Emperor of the Song dynasty | |||||||||||||

| Reign | 23 February 1100 – 18 January 1126 | ||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Emperor Zhezong | ||||||||||||

| Successor | Emperor Qinzong | ||||||||||||

| Born |

Zhao Ji 7 June 1082 | ||||||||||||

| Died | 4 June 1135 (aged 52) | ||||||||||||

| Empresses |

Empress Xiangong Empress Xiansu Empress Mingda Empress Mingjie Empress Xianren | ||||||||||||

| Concubines | 143 concubines | ||||||||||||

| Issue | 38 sons and 34 daughters | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| House | House of Zhao | ||||||||||||

| Father | Emperor Shenzong | ||||||||||||

| Mother | Empress Qinci | ||||||||||||

| Emperor Huizong of Song | |||||||

| Chinese | 宋徽宗 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literal meaning | "Emblemed Ancestor of the Song" | ||||||

| |||||||

| Zhao Ji | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 趙佶 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 赵佶 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Duke Hunde | |||||||

| Chinese | 昏德公 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Besotted Duke | ||||||

| |||||||

Emperor Huizong of Song (7 June 1082 – 4 June 1135), personal name Zhao Ji, was the eighth emperor of the Song dynasty in China. Born as the 11th son of Emperor Shenzong, he ascended the throne in 1100 upon the death of his elder brother and predecessor, Emperor Zhezong, because Emperor Zhezong's only son died prematurely. He lived in luxury, sophistication and art in the first half of his life. In 1126, when the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty invaded the Song dynasty during the Jin–Song Wars, Emperor Huizong abdicated and passed on his throne to his eldest son, Emperor Qinzong, while he assumed the honorary title of Taishang Huang (or "Retired Emperor"). The following year, the Song capital, Bianjing, was conquered by Jin forces in an event historically known as the Jingkang Incident. Emperor Huizong, along with Emperor Qinzong and the rest of their family, were taken captive by the Jurchens and brought back to the Jin capital, Huining Prefecture in 1128. The Jurchen ruler, Emperor Taizong, gave the former Emperor Huizong a title, Duke Hunde (literally "Besotted Duke"), to humiliate him. Emperor Huizong died in Wuguocheng after spending about nine years in captivity.

Despite his incompetence in rulership, Emperor Huizong was known for his promotion of Taoism and talents in poetry, painting, calligraphy and music. He sponsored numerous artists at his imperial court, and the catalogue of his collection listed over 6,000 known paintings.[1]

Life

Emperor Huizong, besides his partaking in state affairs that favoured the reformist party that supported Wang Anshi's New Policies, was a cultured leader who spent much of his time admiring the arts. He was a collector of paintings, calligraphy, and antiques of previous dynasties, building huge collections of each for his amusement. He wrote poems of his own, was known as an avid painter, created his own calligraphy style, had interests in architecture and garden design, and even wrote treatises on medicine and Taoism.[2] He assembled an entourage of painters that were first pre-screened in an examination to enter as official artists of the imperial court, and made reforms to court music.[2] Like many learned men of his age, he was quite a polymath personality, and is even considered to be one of the greatest Chinese artists of all time. However, his reign would be forever scarred by the decisions made (by counsel he received) on handling foreign policy, as the end of his reign marked a period of disaster for the Song Empire.

Jurchen invasion

Emperor Huizong neglected the military, and the Song dynasty became increasingly weak and at the mercy of foreign invaders, despite his recasting of the symbolic Nine Tripod Cauldrons in 1106 in an attempt to assert his authority.[3] When the Jurchens founded the Jin dynasty and attacked the Khitan-led Liao dynasty to the north of the Song, the Song dynasty allied with the Jin dynasty and attacked the Liao from the south. This succeeded in destroying the Liao, a longtime enemy of the Song. However, an enemy of the even more formidable Jin dynasty was now on the northern border. Not content with the annexation of the Liao domain, and perceiving the weakness of the Song army, the Jurchens soon declared war on their former ally, and by the beginning of 1126 the troops of the Jin "Western Vice-Marshal" Wolibu crossed the Yellow River and came in sight of Bianjing, the capital of the Song Empire. Stricken with panic, Emperor Huizong abdicated on 18 January 1126 in favour of his son, now known as Emperor Qinzong (欽宗), and departed the capital.[4]

Overcoming the walls of Bianjing was a difficult undertaking for the Jurchen cavalry, and this, together with fierce resistance from some Song officials who had not totally lost their nerve, as Emperor Huizong had, resulted in the Jurchens lifting the siege of Bianjing and returning north. The Song Empire, however, had to sign a humiliating treaty with the Jin Empire, agreeing to pay a colossal war indemnity and to give a tribute to the Jurchens every year. From 1126 until 1138, refugees from the Song Empire migrated south towards the Yangtze River valley.[5]

But even such humiliating terms could not save the Song dynasty. Within a matter of months, the troops of both Jurchen vice-marshals, Wolibu and Nianhan,[6] were back south again, and this time they were determined to overcome the walls of Bianjing. After a bitter siege, the Jurchens eventually entered Bianjing on 9 January 1127, and many days of looting, rapes, and massacre followed. Emperor Huizong, his son Emperor Qinzong, as well as the entire imperial court and harem were captured by the Jurchens in an event known historically as the Jingkang Incident, and transported north, mostly to the Jin capital of Shangjing (in present-day Harbin). One of the sons of Emperor Huizong managed to escape to southern China where, after many years of struggle, he would establish the Southern Song dynasty, of which he was the first ruler, Emperor Gaozong.

Emperors Huizong and Qinzong were demoted to the rank of commoners by the Jurchens on 20 March 1127. Then on 10 May 1127, Emperor Huizong was deported to Heilongjiang, where he spent the last eight years of his life as a captive. In a humiliating episode, in 1128 the two former Song emperors had to venerate the Jin ancestors at their shrine in Shangjing, wearing mourning dress.[7] The Jurchen ruler, Emperor Taizong, granted the two former Song emperors degrading titles to humiliate them: Emperor Huizong was called "Duke Hunde" (昏德公; literally "Besotted Duke") while Emperor Qinzong was called "Marquis Chonghun" (重昏侯; literally "Doubly Besotted Marquis").[7]

In 1137, the Jin Empire formally notified the Southern Song Empire about the death of their former Emperor Huizong.[7] Emperor Huizong, who had lived in opulence and art for the first half of his life, died a broken man in faraway northern Heilongjiang in June 1135, at the age of 52.

A few years later (1141), as the peace negotiations leading up to the Treaty of Shaoxing between the Jin and the Song empires were proceeding, the Jin Empire posthumously honored the former Emperor Huizong with the neutral-sounding title of "Prince of Tianshui Commandery" (天水郡王), after a commandery in the upper reaches of the Wei River.

Art, calligraphy, music, and culture

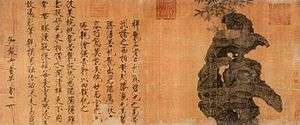

Emperor Huizong was a great painter, poet, and calligrapher. He was also a player of the guqin (as exemplified by his famous painting 聽琴圖 Listening to the Qin); he also had a Wanqin Tang (萬琴堂; "10,000 Qin Hall") in his palace.

The emperor took huge efforts to search for art masters. He established the "Hanlin Huayuan" (翰林畫院; "Hanlin imperial painting house") where top painters around China shared their best works.

The primary subjects of his paintings are birds and flowers. Among his works is Five-Colored Parakeet on Blossoming Apricot Tree. He also recopied Zhang Xuan's painting Court Ladies Preparing Newly Woven Silk, and Emperor Huizong's reproduction is the only copy of that painting that survives today.

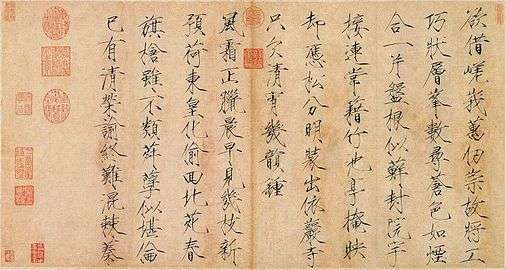

Emperor Huizong invented the "Slender Gold" (瘦金體) style of calligraphy. The name "Slender Gold" came from the fact that the emperor's writing resembled gold filament, twisted and turned.

One of the emperor's era names, Xuanhe, is also used to describe a style of mounting paintings in scroll format. In this style, black borders are added between some of the silk planes.

In 1114, following a request from the Goryeo ruler Yejong, Emperor Huizong sent to the palace in the Goryeo capital at Gaeseong a set of musical instruments to be used for royal banquet music. Two years later, in 1116, he sent another, even larger gift of musical instruments (numbering 428 in total) to the Goryeo court, this time yayue instruments, beginning that nation's tradition of aak.[8]

Emperor Huizong was also a great tea enthusiast. He wrote the Treatise on Tea, the most detailed and masterful description of the Song sophisticated style of tea ceremony.

Emperor Huizong of Song, Ladies making silk, (a remake of an 8th-century original by artist Zhang Xuan)

Emperor Huizong of Song, Ladies making silk, (a remake of an 8th-century original by artist Zhang Xuan)

Emperor Huizong of Song (Poem and Calligraphy)

Emperor Huizong of Song (Poem and Calligraphy) Emperor Huizong of Song, Plum and Birds

Emperor Huizong of Song, Plum and Birds Emperor Huizong of Song, Golden Pheasant and Cotton Rose Flowers

Emperor Huizong of Song, Golden Pheasant and Cotton Rose Flowers Emperor Huizong of Song, Dragon Stone

Emperor Huizong of Song, Dragon Stone Emperor Huizong of Song, Cranes 1112

Emperor Huizong of Song, Cranes 1112 Emperor Huizong of Song, Classic Thousand-character Grass script

Emperor Huizong of Song, Classic Thousand-character Grass script

Titles from birth

- Prince of Suining Commandery (遂寧郡王)

- Prince of Duan (端王)

- Emperor

- Emperor Jiaozhu Daojun (教主道君皇帝)

- Duke Hunde (昏德公)

- Prince of Tiansui Commandery (天水郡王)

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Emperor Huizong of Song. |

- List of emperors of the Song dynasty

- Architecture of the Song dynasty

- Culture of the Song dynasty

- Economy of the Song dynasty

- History of the Song dynasty

- Society of the Song dynasty

- Technology of the Song dynasty

Notes

- ↑ Ebrey, Cambridge, 149.

- 1 2 Ebrey, 165.

- ↑ Book of Song – Scroll 66

- ↑ Frederick W. Mote (2003). Imperial China: 900-1800. Harvard University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-674-01212-7.

- ↑ Robert Hymes (2000). John Stewart Bowman, ed. Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. Columbia University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-231-11004-4.

- ↑ Tao (1976). Pages 20–21.

- 1 2 3 Franke (1994), p. 233-234.

- ↑

References

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley. (2013). Emperor Huizong (Harvard University Press; 2013) 661 pages; scholarly biography online review

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley. (1999). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-66991-X (paperback).

- Ebrey, Walthall, and Palais (2006). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Boston: Houghton and Mifflin.

- Jing-shen Tao (1976) The Jurchen in Twelfth-Century China. University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-95514-7.

- Herbert Franke, Denis Twitchett. Alien Regimes and Border States, 907–1368 (Cambridge History of China, vol. 6). Cambridge University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-521-24331-9. Partial text on Google Books.

- Huiping Pang (2009), "Strange Weather: Art, Politics, and Climate Change at the Court of Northern Song Emperor Huizong," Journal of Song-Yuan Studies, Volume 39, 2009, pp. 1–41. ISSN 1059-3152.

- Please see: References section in the guqin article for a full list of references used in all qin related articles.

| Emperor Huizong of Song Born: November 2 1082 Died: June 4 1135 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Emperor Zhezong |

Emperor of the Song Dynasty 1100–1126 |

Succeeded by Emperor Qinzong |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Vacant Title last held by Emperor Zhaozong of Tang |

Retired Emperor of China 1126–1135 |

Vacant Title next held by Emperor Gaozong of Song |