Chinese Spring Offensive

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

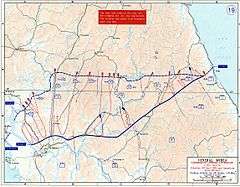

The Chinese Spring Offensive, also known as the Chinese Fifth Phase Offensive, was a military operation conducted by the Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA) during the Korean War. Mobilizing three field armies totaling 700,000 men for the operation, the Chinese command conducted their largest offensive operation since Second Phase Offensive in November and December 1950. The operation took place in the summer of 1951 and aimed at permanently driving the UN forces off the Korean peninsula.

The offensive's first thrust fell upon the multinational units of US I Corps, which fiercely resisted at the Battle of the Imjin River and the Battle of Kapyong which took place at the same time over the period 22–25 April 1951, blunting the impetus of the offensive, which was halted at the "No-name Line" north of Seoul. On 15 May 1951, the Chinese commenced the second impulse of the Spring Offensive and attacked the Republic of Korea Army and the US X Corps in the east. Although initially successful, they were halted by 20 May. At month's end, the US Eighth Army counterattacked the exhausted Chinese forces, inflicting heavy losses.[6] However, the UN counterattack was halted by the Chinese near the 38th Parallel, beginning a stalemate that lasted until the armistice in 1953.

Background

Chinese intervention

North Korea invaded South Korea on 25 June 1950. But after having conquered much of southern Korea, the North Koreans suffered a crushing defeat after losing much of their army at the Battle of the Pusan Perimeter. With the UN forces on the offensive after landing at Incheon, they soon crossed the 38th Parallel and invaded North Korea in turn. The Chinese government warned that to safeguard their national sovereignty, they would militarily intervene in Korea if American forces crossed the parallel.[7] However, the U.S. president Harry Truman dismissed the warning.[8]

As the UN forces raced to the Yalu River after taking Pyongyang, the Chinese launched their first offensive of the war. Undeterred, the UN Command under Douglas MacArthur initiated the "Home-By-Christmas" offensive aimed at permanently evicting the Chinese from Korea. In response, the Chinese command soon launched a full-scale counteroffensive that drove them out of North Korea at the end of the year 1950, carrying the war back south of the 38th Parallel, with Seoul falling for the second time at the hands of the Communists. Reeling from these defeats, the UN Command sought to commence ceasefire negotiations with the Chinese government in January 1951, but Mao Zedong and his colleagues ardently refused; as a result, the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 498 on 1 February, condemning China as an aggressor, and demanded that it's forces withdraw from Korea.[9]

UN counterattacks

The UN Command, under the new commander Matthew Ridgway, staged counterattacks northward that soon retook Seoul from the Communists, and brought the fighting to the hills situated along the 38th Parallel. But the PVA commanders soon launched their counterattack, with their Fourth Phase Campaign, but after gaining ground, this too was halted by UN troops.

The Chinese soldiers by this time were had been badly mauled, and were worn out from incessant combat and exhaustion. To make matters worse, the U.S. Air Force had been constantly bombing their supply lines, further weakening their fighting capabilities due to lack of food and supplies. The UN forces, on the other hand, were widely dispersed to their front of their battle formation due to recent counteroffensives that took place earlier.

Prelude

The PVA Commander-in-Chief Peng Dehuai and the rest of his command, determined to evict the UN Forces from Korea permanently, reformed his frontline forces and amassed a strike force of three field armies and three North Korean corps, totaling 700,000 men.[2] Of these, he ordered 270,000 from the 3rd, 9th and 19th Army Groups to be directed for an assault towards Seoul, while the rest were deployed elsewhere on the battlefront with 214,000 men serving as their strategic reserve to be committed for support purposes. The PVA 3rd and 19th Army, under orders from Chairman Mao Zedong, began to enter Korea in February 1951,[10] alongside four field artillery divisions, two long range artillery divisions, four anti-aircraft divisions, one multiple rocket launcher division and four tank regiments,[11] marking the first time the Chinese have deployed such weapons in the war. Peng and the Communist leadership promised their troops that when they had won the battle, they would parading along the streets of Seoul on May Day.[12]

The UN forces were overconfident from their recent victories over the Communists and not aware of this upcoming offensive. There were no defensive works such as minefields or obstacles made. Several South Korean units were badly depleted at the eve of the offensive due to the Chinese Fourth Phase Offensive, although they still have a field strength of more than 150,000 men. Despite having a total field strength of 418,000 troops, there were still gaps between several units on the front. By the time the offensive began, this would prove disastrous for the UN Command in its first impulse, as these problems would repeat the disasters that occurred during the Second Phase Offensive.[13] For example, near the Imjin River, the gap between the Gloucestershire and Royal Ulster Regiments of the British 29th Infantry Brigade was 12 mi (19 km) wide, allowing the Chinese to plug through it and destroy the former during the battle.

Battle

First offensive

The Spring Offensive finally began on 22 April when the Chinese attacked the UN forces at the south bank of the Imjin River, a strategically crucial location heading a historic invasion route to Seoul. The section of the UN line where the battle took place was defended primarily by British forces of the 29th Infantry Brigade, consisting of three British and one Belgian infantry battalion supported by tanks and artillery. Despite facing a numerically superior enemy, the brigade held its positions for three days, repelling several human wave attacks and inflicting more than 10,000 casualties in the process. After being encircled, however, the 1st Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment, nicknamed the 'Glosters', was nearly destroyed and those surviving were captured. In the course of the battle, the brigade suffered 1,091 casualties, including 622 of the Glosters.[14] This was considered by the Chinese as one of their spectacular feats of arms during the war, although their casualties were nearly ten times that of their adversaries. When the units of the 29th Infantry Brigade were ultimately forced to fall back, supported by the defensive rearguard actions of the Filipino contingent during the Battle of Yultong, their actions in the Battle of the Imjin River together with those of other UN forces had blunted the impetus of the Chinese offensive and allowed UN forces to retreat to prepared defensive positions in the area called the "No-name line" just 5 miles north of Seoul, where the Chinese were halted. Both sides then realized that the prospect of the Communists parading along the streets of Seoul during May Day had evaporated.[12] On the other hand, although the UN forces made a strategic gain during the battle by preventing the Chinese from recapturing Seoul, the loss of the regiment caused much controversy in Britain and within the UN Command.[15]

In the Kapyong sector, the offensive saw the 27th British Commonwealth Brigade establish blocking positions in the Kapyong Valley, also one of the key routes south to the capital, Seoul. The two forward battalions—3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (3 RAR) and 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry (2 PPCLI)—occupied positions astride the valley and hastily developed defences on 23 April. As thousands of South Korean soldiers began to withdraw through the valley, the Chinese infiltrated the brigade position under the cover of darkness, and assaulted the Australians on Hill 504 during the evening and into the following day. Although heavily outnumbered, the 27th Brigade held their positions into the afternoon before the Australians withdrew to positions in the rear of the brigade on the evening of 24 April, with both sides having suffered heavy casualties. The Chinese then turned their attention to the Canadians on Hill 677, but during a fierce night battle they were unable to dislodge them. The fighting helped blunt the Chinese offensive and the actions of the Australians and Canadians at Kapyong were important in helping to prevent a breakthrough on the United Nations Command central front, and ultimately the capture of Seoul. The two battalions bore the brunt of the assault and stopped an entire Chinese division during the hard fought defensive battle. The next day the Chinese withdrew back up the valley to their north, in order to regroup for the second impulse of the offensive.[16]

Second offensive

Even though the Communist forces lost the strategic initiative after the first offensive per Peng's reports, Mao still insisted that the second phase of the offensive be carried out. On 15 May 1951, the PVA Command recommenced the Second Spring Offensive and attacked the South Korean Army and the US X Corps in the east at the Soyang River with 150,000 men. After taking the Hwacheon Reservoir and gaining initial success, they were halted by 20 May.[17] At month's end, the US Eighth Army counterattacked and regained "Line Kansas", just north of the 38th parallel.[18] During the final days of the Fifth Phase Campaign, the main body of the 180th Division was encircled during a UN counterattack. After days of hard fighting, the division fragmented, and the regiments fled in all directions. Soldiers either deserted, or were abandoned by their officers during failed attempts to wage guerrilla warfare, without the support of the local people. Finally, out of ammunition and food, some 5,000 soldiers were captured. The division commander and other officers who escaped were subsequently investigated and demoted on return to China.[6] Attempts to dislodge the Communist forces elsewhere near the 38th Parallel especially in the areas beyond "Line Kansas", however, were also blunted by the PVA 42nd and 47th Corps which were quickly rushed to the front on 27 May to relieve the situation.[4] Using probing and hit-and-run tactics in the night, they forced the UN forces to break off their pursuit, thus failing in an attempt to gain any area immediately north of the line. This forced the UN counterattack to grind to a halt on 1 June, and started the stalemate which lasted until the armistice of 1953.

Aftermath

The Spring Offensive would be the last all-out offensive operation of the Chinese for the duration of the war. Their objective to permanently drive the United Nations out of Korea had failed, but they also managed to inflict such losses that any UN operations to retake lost ground were delayed for several weeks after the offensive as well as forcing them to make only limited offensives throughout the war.[1] On the other hand, the Chinese and North Koreans also made sufficient gains in territory southeast of the 38th Parallel so that the UN Command did not have the sufficient strength to retake them for the rest of the war. One example of this is the city of Kaesong, which was under control by UN forces since Operation Courageous but was captured during the offensive, and to this day is controlled by North Korea. The Chinese offensive also helped form the post-war border between North and South Korea. These events may be considered a tactical gain for the Chinese despite their losses, but as an operational failure because they failed to unite the peninsula under communism. For the UN Command, although they failed to recapture some areas that were lost near the 38th Parallel, they achieved the strategic goal of keeping the Communists at bay whilst preventing them from conquering all of the peninsula. However, it was also an operational setback for them since they failed to drive the Communists, battered but not yet beaten in battle, north of the 38th Parallel completely. Overall, it was a stalemate for both sides given the results and losses.

The presence of UN forces at the northeast of the 38th Parallel, however, prompted the PVA Command to plan a limited offensive dubbed the "Six Phase Campaign".[19] But the armistice negotiations that began on 10 June at Kaesong forced both sides to dig in at their respective positions across the 38th Parallel.[20] Despite the offensive being called off on 4 September, however, it allowed the PVA 20th Army to be deployed in the Kumsong area by the early days of the month, with many more crossing the Yalu river, thus rapidly replacing the losses they suffered during the offensive at the end of the month.[21] The planned offensive was commenced albeit later shortly before the 1953 armistice, eventually joining the Battle of Kumsong in which the Chinese won another major victory.[22]

With both sides having suffered heavy losses during the offensive, the front became relatively static for the months following. The mobile warfare of rapid movement that dominated the early stages of the war has completely eclipsed following the offensive and the war would be on the stage similar to the trench warfare of the First World War in which both sides entrenched and exchanged little territory with each other while they each suffer horrendous losses. Both sides concluded that no belligerent was capable of uniting the peninsula under their respective banners. The north-south dividing line along the peninsula returned to almost its initial position before the outbreak of the war.

See also

Notes

- Footnotes

- ↑ The Chinese forces made substantial gains throughout the offensive but failed to drive the United Nations forces out of the Korean peninsula. Efforts by the US 8th Army and ROK Army to dislodge the Chinese north of the 38th Parallel, however, also failed a few days before the armistice negotiations happening in Kaesong on 10 June.[1]

- Citations

- 1 2 Zhang 2004, p. 145.

- 1 2 3 O'Neill 1985, p. 132.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, p. 379.

- 1 2 Zhang 1995, p. 152.

- ↑ Millett 2010, pp. 441, 452.

- 1 2 Chinese Question Role in Korean War, from POW-MIA InterNetwork Archived October 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Stokesbury 1990, p. 83.

- ↑ Offner 2002, p. 390.

- ↑ "Resolution 498(V) Intervention of the Central People's Government of People's Republic of China in Korea". United Nations. 1951-02-01. and "Cold War International History Project's Cold War Files". Wilson Center.

- ↑ Hu & Ma 1987, pp. 37.

- ↑ Zhang 1995, p. 148.

- 1 2 http://www.marines.mil/Portals/59/Publications/U.S.%20Marines%20in%20the%20Korean%20War%20%20PCN%2010600000100_16.pdf

- ↑ Johnston 2003, p. 89.

- ↑ Imjin River National army Museum

- ↑ Johnston 2003, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Coulthard-Clark 2001, pp. 263–265.

- ↑ Stokesbury 1990, pp. 136–137.

- ↑ Stokesbury 1990, pp. 137–138.

- ↑ Zhang 1995, pp. 157–158.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, pp. 553, 579.

- ↑ Zhang 1995, pp. 157, 159–160.

- ↑ Zhang 1995, p. 243.

References

- Appleman, Roy (1990). Ridgway Duels for Korea. Military History Series. 18. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-0-89096-432-3.

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (2001). The Encyclopaedia of Australia's Battles (Second ed.). Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen and Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86508-634-7.

- Hu, Guang Zheng (胡光正); Ma, Shan Ying (马善营) (1987). Chinese People's Volunteer Army Order of Battle (中国人民志愿军序列) (in Chinese). Beijing: Chinese People's Liberation Army Publishing House. OCLC 298945765.

- Offner, Arnold A. (2002). Another Such Victory: President Truman and the Cold War, 1945–1953. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4774-1.

- O'Neill, Robert (1985). Australia in the Korean War 1950–53: Combat Operations. Volume II. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Australian War Memorial. ISBN 978-0-642-04330-6.

- Millett, Allan R. (2010). The War for Korea, 1950–1951: They Came From the North. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1709-8.

- Mossman, Billy C. (1990). United States Army in the Korean War: Ebb and Flow: November 1950 – July 1951. Washington D.C.: Center of Military History, US Army. ISBN 978-1-131-51134-4.

- Johnston, William (2003). A War of Patrols: Canadian Army Operations in Korea. Vancouver, British Columbia: UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-1008-1.

- Stokesbury, James L. (1990). A Short History of the Korean War. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-688-09513-0.

- Zhang, Shu Guang (1995). Mao's Military Romanticism: China and the Korean War, 1950–1953. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0723-5.

- Zhang, Xiao Ming (2004). Red Wings Over the Yalu: China, the Soviet Union, and the Air War in Korea. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 1-58544-201-1.

Coordinates: 37°56′34″N 126°56′21″E / 37.9427°N 126.9392°E

.jpg)