Hückel method

The Hückel method or Hückel molecular orbital method (HMO), proposed by Erich Hückel in 1930, is a very simple linear combination of atomic orbitals molecular orbitals (LCAO MO) method for the determination of energies of molecular orbitals of pi electrons in conjugated hydrocarbon systems, such as ethene, benzene and butadiene.[1][2] It is the theoretical basis for the Hückel's rule. It was later extended to conjugated molecules such as pyridine, pyrrole and furan that contain atoms other than carbon, known in this context as heteroatoms.[3] The extended Hückel method developed by Roald Hoffmann is computational and three-dimensional and was used to test the Woodward–Hoffmann rules.[4]

It is a very powerful educational tool, and details appear in many chemistry textbooks.

Hückel characteristics

The method has several characteristics:

- It limits itself to conjugated hydrocarbons.

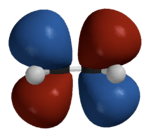

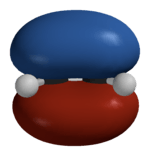

- Only pi electron molecular orbitals (MO's) are included because these determine the general properties of these molecules and the sigma electrons are ignored. This is referred to as sigma-pi separability. It is justified by the orthogonality of sigma and pi orbitals in planar molecules. For this reason, the Hückel method is limited to planar systems.

- The method takes as inputs the LCAO MO Method, the Schrödinger equation and simplifications based on orbital symmetry considerations. Interestingly the method does not take in any physical constants.

- The method predicts how many energy levels exist for a given molecule, which levels are degenerate and it expresses the MO energies as the sum of two other energy terms, called alpha, the energy of an electron in a 2p-orbital, and beta, an interaction energy between two p orbitals which are still unknown but importantly have become independent of the molecule. In addition it enables calculation of charge density for each atom in the pi framework, the bond order between any two atoms, and the overall molecular dipole moment.

Hückel results

The results for a few simple molecules are tabulated below:

| Molecule | Energy | Frontier orbital | HOMO–LUMO energy gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 = α - β | LUMO | −2β | |

| E2 = α + β | HOMO | ||

| E1 = α + 1.62β | |||

| E2 = α + 0.62β | HOMO | −1.24β | |

| E3 = α − 0.62β | LUMO | ||

| E4 = α − 1.62β | |||

| E1 = α + 2β | |||

| E2 = α + β | |||

| E3 = α + β | HOMO | −2β | |

| E4 = α − β | LUMO | ||

| E5 = α − β | |||

| E6 = α − 2β | |||

| E1 = α + 2β | |||

| E2 = α | SOMO | 0 | |

| E3 = α | SOMO | ||

| E4 = α − 2β | |||

| Table 1. Hückel method results. Lowest energies of top α and β are both negative values.[5] HOMO/LUMO/SOMO = Highest occupied/lowest unoccupied/singly-occupied molecular orbitals. | |||

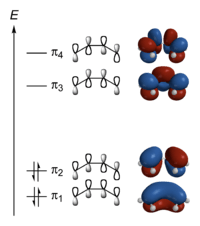

The theory predicts two energy levels for ethylene with its two pi electrons filling the low-energy HOMO and the high energy LUMO remaining empty. In butadiene the 4 pi electrons occupy 2 low energy MO's, out of a total of 4, and for benzene 6 energy levels are predicted, two of them degenerate.

For linear and cyclic systems (with n atoms), general solutions exist:[6]

- Linear:

- Cyclic:

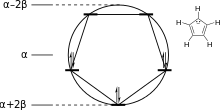

The energy levels for cyclic systems can be predicted using the Frost circle mnemonic. A circle centered at α with radius 2β is inscribed with a polygon with one vertex pointing down; the vertices represent energy levels with the appropriate energies.[7] A related mnemonic exists for linear systems.[8]

Many predictions have been experimentally verified:

- The HOMO–LUMO gap, in terms of the β constant, correlates directly with the respective molecular electronic transitions observed with UV/VIS spectroscopy. For linear polyenes, the energy gap is given as:

- The predicted MO energies as stipulated by Koopmans' theorem correlate with photoelectron spectroscopy.[10]

- The Hückel delocalization energy correlates with the experimental heat of combustion. This energy is defined as the difference between the total predicted pi energy (in benzene 8β) and a hypothetical pi energy in which all ethylene units are assumed isolated, each contributing 2β (making benzene 3 × 2β = 6β).

- Molecules with MO's paired up such that only the sign differs (for example α ± β) are called alternant hydrocarbons and have in common small molecular dipole moments. This is in contrast to non-alternant hydrocarbons, such as azulene and fulvene that have large dipole moments. The Hückel theory is more accurate for alternant hydrocarbons.

- For cyclobutadiene the theory predicts that the two high-energy electrons occupy a degenerate pair of MO's that are neither stabilized or destabilized. Hence the square molecule would be a very reactive triplet diradical (the ground state is actually rectangular without degenerate orbitals). In fact, all cyclic conjugated hydrocarbons with a total of 4nπ electrons share this MO pattern, and this forms the basis of Hückel's rule.

- Dewar reactivity numbers deriving from the Hückel approach correctly predict the reactivity of aromatic systems with nucleophiles and electrophiles.

Mathematics behind the Hückel method

The Hückel method can be derived from the Ritz method, with a few further assumptions concerning the overlap matrix S and the Hamiltonian matrix H.

It is assumed that the overlap matrix S is the identity matrix. This means that overlap between the orbitals is neglected and the orbitals are considered orthogonal. Then the generalised eigenvalue problem of the Ritz method turns into an eigenvalue problem.

The Hamiltonian matrix H = (Hij) is parametrised in the following way:

- Hii = α for C atoms and α + hAβ for other atoms A.

- Hij = β if the two atoms are next to each other and both C, and kAB β for other neighbouring atoms A and B.

- Hij = 0 in any other case.

The orbitals are the eigenvectors, and the energies are the eigenvalues of the Hamiltonian matrix. If the substance is a pure hydrocarbon, the problem can be solved without any knowledge about the parameters. For heteroatom systems, such as pyridine, values of hA and kAB have to be specified.

Hückel solution for ethylene

In the Hückel treatment for ethylene,[11] the molecular orbital is a linear combination of the 2p atomic orbitals at carbon with their ratios :

This equation is substituted in the Schrödinger equation:

- with the Hamiltonian and the energy corresponding to the molecular orbital

to give:

This equation is multiplied by and integrated to give the equation:

The same equation is multiplied by and integrated to give the equation:

This really can be represented as a matrix. After converting this set to matrix notation,

Or more simply as a product of matrices.

where:

All diagonal Hamiltonian integrals are called coulomb integrals and those of type , where atoms i and j are connected, are called resonance integrals. The Hückel method assumes that all overlap integrals equal the Kronecker delta, , and all nonzero resonance integrals are equal. Resonance integral is nonzero when the atoms i and j are bonded.

Other assumptions are that the overlap integral between the two atomic orbitals is 0

leading to these two homogeneous equations:

dividing by :

Substituting for :

This is convenient for computation, but it is also convenient as the energy and coefficients can be easily found:

The trivial solution gives both wavefunction coefficients c equal to zero which is not useful so the other (non-trivial) solution is:

which can be solved by expanding its determinant:

Knowing that , the energy levels can be found to be:

The coefficients can be found by using the previous relationship determined:

Only one equation is necessary however:

The second constant can be replaced giving the following wave equation.

After normalization, the coefficient is obtained:

Leaving

The constant β in the energy term is negative; therefore, with is the lower energy corresponding to the HOMO energy and with is the LUMO energy.

Hückel solution for butadiene

In the Hückel treatment for butadiene, the MO is a linear combination of the 4p AO's at carbon with their ratios :

The secular equation is:

which leads to

and:

See also

External links

- "Hückel method" at chem.swin.edu.au, webpage: mod3-huckel.

- N. Goudard; Y. Carissan; D. Hagebaum-Reignier; S. Humbel (2008). "HuLiS : Java Applet – Simple Hückel Theory and Mesomery – program logiciel software" (in French). Retrieved 19 August 2010.

Further reading

- The HMO-Model and its applications: Basis and Manipulation, E. Heilbronner and H. Bock, English translation, 1976, Verlag Chemie.

- The HMO-Model and its applications: Problems with Solutions, E. Heilbronner and H. Bock, English translation, 1976, Verlag Chemie.

- The HMO-Model and its applications: Tables of Hückel Molecular Orbitals, E. Heilbronner and H. Bock, English translation, 1976, Verlag Chemie.

References

- ↑ E. Hückel, Zeitschrift für Physik, 70, 204 (1931); 72, 310 (1931); 76, 628 (1932); 83, 632 (1933).

- ↑ Hückel Theory for Organic Chemists, C. A. Coulson, B. O'Leary and R. B. Mallion, Academic Press, 1978.

- ↑ Andrew Streitwieser, Molecular Orbital Theory for Organic Chemists, Wiley, New York (1961).

- ↑ "Stereochemistry of Electrocyclic Reactions", R. B. Woodward, Roald Hoffmann, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1965; 87(2); 395–397. doi:10.1021/ja01080a054.

- ↑ The chemical bond, 2nd ed., J.N. Murrel, S.F.A. Kettle, J.M. Tedder, ISBN 0-471-90760-X

- ↑ Quantum Mechanics for Organic Chemists. Zimmerman, H., Academic Press, New York, 1975.

- ↑ Frost, A. A.; Musulin, B. (1953). "Mnemonic device for molecular-orbital energies". J. Chem. Phys. 21: 572–573. Bibcode:1953JChPh..21..572F. doi:10.1063/1.1698970.

- ↑ Brown, A.D.; Brown, M. D. (1984). "A geometric method for determining the Huckel molecular orbital energy levels of open chain, fully conjugated molecules". J. Chem. Educ. 61: 770. Bibcode:1984JChEd..61..770B. doi:10.1021/ed061p770.

- ↑ "Use of Huckel Molecular Orbital Theory in Interpreting the Visible Spectra of Polymethine Dyes: An Undergraduate Physical Chemistry Experiment". Bahnick, Donald A., J. Chem. Educ. 1994, 71, 171.

- ↑ Huckel theory and photoelectron spectroscopy. von Nagy-Felsobuki, Ellak I. J. Chem. Educ. 1989, 66, 821.

- ↑ Quantum chemistry workbook, Jean-Louis Calais, ISBN 0-471-59435-0.